The Dragon’s Voice

Welcome to the first issue of 2022.

In this issue, we have an article on the WWI experiences of Amelia Earhart, which did not involve her doing any flying, an article on the use of the media as a weapon in WWI, and our own Bridget Geoghegan’s extensive account of who’s who in Beaumaris churchyard.

At a time of tension in the world, and I write this on St Valentine’s Day, it is perhaps worthwhile looking back at the period of history that we are all interested in. In particular, some of those in the political world forget, or do not know of, the period immediately after the end of WWI when there was chaos for years in the East. Professor Robert Gerwarth of University College Dublin spoke recently to the Durham WFA about this period (and he has written a wonderful book on the era “The Vanquished” which is reviewed on our website - https://www.nwwfa.org.uk/index.php/book-reviews/gerwarth-the-vanquished By the way, Robert is German).

The Western allies invaded Russia from 1918 in an ill-fated and disastrous attempt to crush the Bolsheviks in the Russian civil war. At much the same time, there was the Soviet-Polish war when the Poles got as far east as Kiev, and north into Belarus and Lithuania. The Soviet army was subsequently stopped in its westward advance at the gates of Warsaw in August 1920, with the help of a French contingent lead by Marechal Maxime Weygand, and Charles de Gaulle as his staff officer.

Leaping forward to another war, if you have the chance to visit the WWII Blockhaus Museum at Ganspette in Northern France, which was a V1 and V2 rocket factory and launch site, there is an exhibit on the slave workers who laboured there, many of whom were from Eastern Europe. One of the exhibits refers to the scale of Russian casualties in WWII – 16 million civilians and 5 million military casualties.

So, the West interfering in Russia is a recurring theme, with unhappy consequences all round. After all, the justification for studying history is not to repeat the mistakes of the past. Perhaps a lesson for politicians of all sides today?

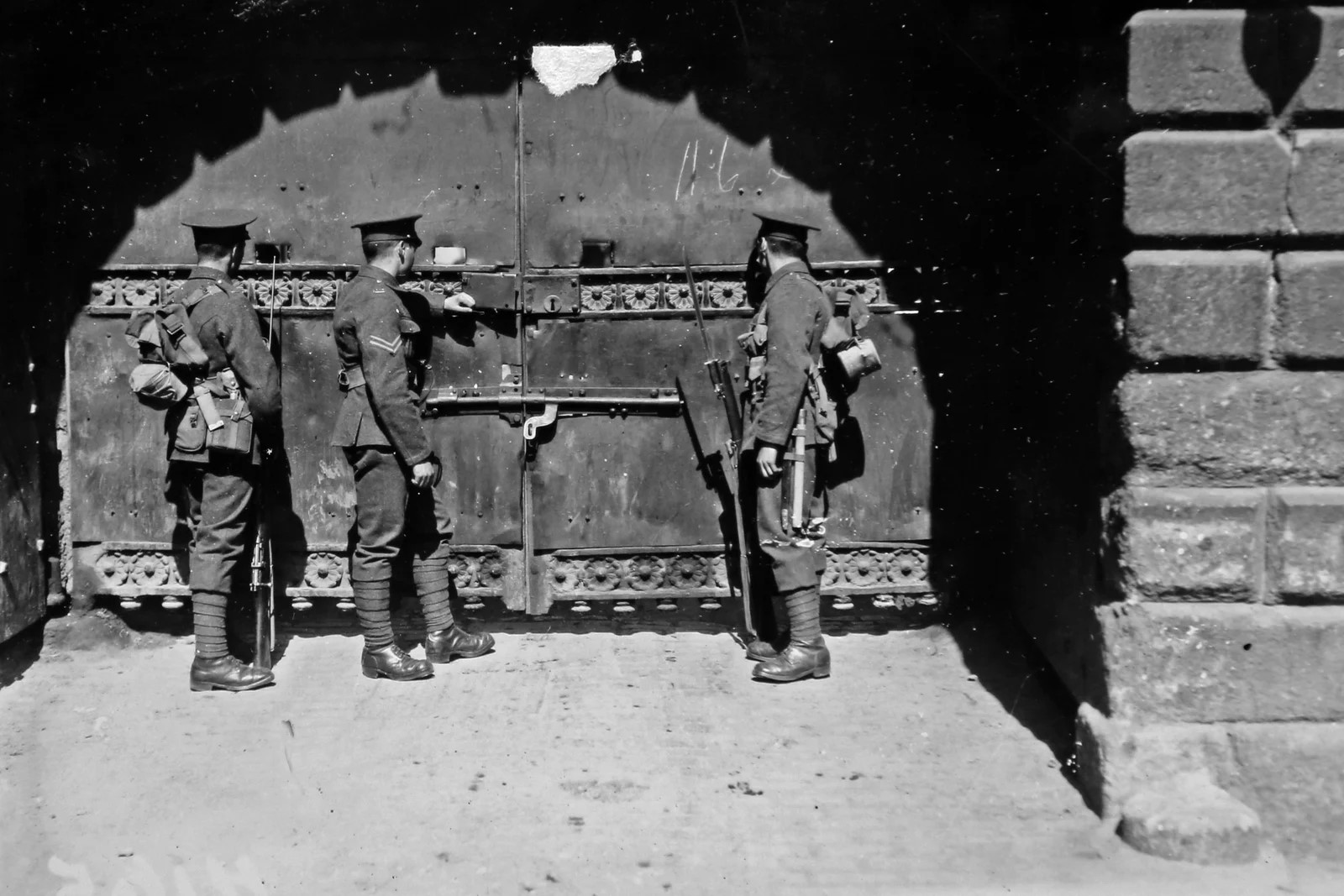

On another theme, I have not seen any mention in the so-called national press, or other media, of the centenary of the UK losing 20% of its land area? In other words, it is the centenary of the formation of the Irish Free State. The whole episode from 1916 to 1922 is an object lesson of a British government making a mess of a situation. There were people who knew better, but they were ignored. So, we have the photo below of the seat of British power in Ireland, Dublin Castle, being handed over to the new provisional government in January 1922. But when did British troops leave Dublin? The answer is as late as December 1922. General Nevil Macready, who was GOC Ireland and whose father was Irish, thought that 5000 troops in the Dublin garrison was a big enough number to be a target but not big enough to do anything. When did British troops leave the Irish Free State? Would you believe 1938, which was when Churchill surrendered the so-called “Treaty ports” to Irish control, little more than a year before the start of WWII and the Battle of the Atlantic. (The Treaty ports were retained by the British after creation of the Irish Free State. They were Lough Swilly in NW Ireland, Berehaven in the extreme SW and Cobh (Queenstown) in Cork Harbour in the South.) A lot of this does seem to have escaped the attention of historians in the UK, which is a shame as it is as much a part of English, Welsh and Scottish history as it is of Irish history (from which comment I will exonerate the WFA’s faithful including of course Gary Sheffield, Peter Simpkins and Stephen Badsey to name but three!)

Kevin O’Higgins, Michael Collins (centre) and Eamon Duggan leave Dublin Castle

British soldiers guarding Dublin Castle during the handover – January 1922

Amelia Earhart’s WWI experiences

Mark Bardenwerper Sr of the West Coast WFA in the USA recently posted this item from Historia Obscurum on their Facebook page.

Were it not for the First World War, Amelia Earhart's life might have taken a very different course. Earhart was contemplating studying medicine when she visited her sister, Grace, in Toronto, Ontario, in 1917, and for the first time saw throngs of wounded, maimed soldiers recuperating from horrible experiences at the front.

Earhart decided to volunteer with the Canadian Voluntary Aid Detachment (photograph above is of her in her uniform), and began working as a nurse's aid at the Spadina Military Hospital in Toronto. Her time working with the wounded made two major changes in the course of her life. The first is that she became an avowed and outspoken pacifist. The second would make her a household name.

It was while working at the hospital that she began to meet (as she called them) the "very young and very handsome" military pilots, and she became enthralled with their stories of the excitement of dancing through the clouds and seeing the earth fall away below.

Earhart began spending her free time exploring the airfields around Toronto, which, fortuitously, happened to be the headquarters city for the Royal Canadian Flying Corps.

It was during one of the airshows put on by local pilots that the flying bug took hold of Earhart, and she never looked back. Returning to the United States after the war, she jumped into aviation, and made her mark as an early pioneer.

"I think that I can attribute my aviation career to what I experienced... in Toronto."

~ Amelia Earhart, 1932

The First World War as a media event

by Christian Götter

Original in German, this version displayed in English▾

Published: 2021-08-26

Introduction by the editor

This is a recently published article by a German academic on how the combatant governments sought to channel major events during WWI through their own media and that of other countries to influence their own citizens and those of allies and neutrals. He uses the Battle of Jutland to illustrate his approach. (Incidentally, it is the Battle of Skagerrak in German which makes more sense, as that is an area of sea and Jutland is an area of land!) We have left out the huge appendix with the references, but this can be accessed at

http://ieg-ego.eu/de/threads/buendnisse-und-kriege/krieg-als-motor-des-transfers/christian-goetter-der-erste-weltkrieg-als-medienereignis

In essence, the author analyses how the two sides at Jutland “spun” the battle, which was British defeat, a view I agree view, but that makes the ultimate strategic outcome even more convincing, not less.

During the course of the First World War, the armed forces involved increasingly attempted to construct individual incidents of the war as media events in an effort to use them to influence the course of the war overall. This gave rise to narratives that were, to a degree, in competition with each other, although they were based on the same occurrences. This phenomenon is illustrated below via the example of the Battle of Jutland, a naval battle of the conflict. The First World War, it is argued, was not a single media event, but was constructed in the form of multiple media events – even though propaganda experts on the Allied side and German right-wing nationalist circles on the other side retrospectively attempted to re-construct the conflict as a whole as having been shaped by the media, and thus as 'one' media event.

Table of Contents

- The First World War as a Media Event

- The Media Battle of Jutland

- Media Events in the Media Strategies of the Armed Forces

- Aftermath of the First World War as a Media Event

The First World War as a Media Event

The First World War was not a media event.1 However, so this article’s hypothesis, during the course of the conflict, the combatants increasingly aimed at the construction of media events as part of their own war effort and attempted to use them to influence their own populations, neutral states, their respective allies and enemies. Individual occurrences that were highlighted as media events from among the many that made up the war were intended to give structure to the war and provide orientation for the public. Frequently, different constructions of one and the same event competed with each other. According to this interpretation, the First World War was not a media event, but rather consisted of numerous media events (and no less frequently of media non-events), which were constructed by the powers engaged in the conflict.

The war correspondents based at the Austro-Hungarian War Press Office were an example of this. From the beginning of the war, they set about constructing the daily occurrences "at the front" as reportable events for their readers back home solely on the basis of army reports.2 As the war progressed, films – such as the famous The Battle of the Somme – were also increasingly viewed as important. They too created events that linked together into a narrative across the years of trench warfare, in order to strengthen the resolve of the "home front" , although, due to the technological capabilities of the time, these medially (re)constructed events of the war always contained reconstructed scenes.3 Ultimately, the very identity of the respective enemy as a group was created by media events. Even postcards and posters played a central role in the successful construction of the image of the barbaric German enemy as the "Boche" and the "Hun" by French and British propagandists .4

Notwithstanding the variety of different media available, during the First World War newspapers played a dominant role in disseminating news and interpreting the conflict politically,5 and notwithstanding the illustrative power of photographs, it was textual reporting that narrated the war.6 This article thus focuses on textual newspaper reporting while constructing the argument for the central thesis. It first discusses the Battle of Jutland as an example of the construction of a contested media event. This media event is then placed in the context of the considerations of the British and German armed forces involved in the battle regarding the use of media and the construction of media events as an element of warfare. The British and German armed forces were chosen as examples because these central parties to the conflict pursued a particularly active media strategy not only during the war itself, but also beyond it, and they each repeatedly referred to the other's media strategy.7 Finally, a second thesis is briefly introduced – the thesis that after the end of the war there were indeed groups that were interested in reconstructing the First World War retrospectively as one media event. But first, to the Battle of Jutland.

The Media Battle of Jutland

The last survivor of Jutland – HMS Caroline in 1917

The Battle of Jutland8 on 31 May and 1 June 1916 was the largest naval engagement of the war between the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet (Hochseeflotte). It occurred largely "out of sight" not only of the broader public of the nations involved, but also of the military commands of both countries, and even of most of the people directly involved, who experienced it in the interior of ships. Most of the battles of the war exhibited a similar non-visibility, but it was particularly conspicuous in the case of this engagement at sea. The latter was subsequently constructed in the media by the military commands of both sides with the help of journalists as a success for their own side. Versions of the battle were constructed that were in opposition to each other – competing media events. They were intended to convince the people at home and neutral states of one's own victory, to sow doubt in the enemy country, and to motivate one's own allies.

How these opposing media events were constructed with regard to the aims referred to above is illustrated by an analysis of reporting in the liberal Berliner Tageblatt and in The Times of London. In the first week of June 1916, which is focused here, the Berliner Tageblatt was still endeavouring to adhere to the dictate of avoiding domestic political discord (Burgfrieden), and The Times was owned by Lord Northcliffe (Alfred Harmsworth, 1865–1922 ). As regards their coverage of the naval battle, these two newspapers were representative of the respective broader press landscapes of the two countries. In the first two weeks after the naval battle, they reported intensively on the event, publishing official reports, reports by their own journalists, commentaries and leading articles on the topic, as well as reports from the press of enemy countries, of allied countries and of neutral states. They continued to carry reports of the event even after 5 June 1916, when the death of Lord Kitchener (Herbert Kitchener, 1850–1916) temporarily dominated the headlines. After two weeks, the intensity of coverage of the battle began to wane, though it subsequently increased again in response to specific events, such as the publication of the official report of the British commander Admiral John Jellicoe (1859–1935) in July 1916.

The media versions of the battle on both sides were rooted in the progress of the naval engagement. The battle had begun on 31 May 1916 in the sea off Jutland9 and continued until the early hours of 1 June. Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer (1863–1928), who had been appointed commander of the German High Seas Fleet at the beginning of the year, had actually only intended to engage and weaken parts of the British Grand Fleet. But as German radio communications had been decoded, Jellicoe was aware of German plans. He put to sea before the enemy in order to meet him with the entire Grand Fleet. However, initially it was the fast battle cruisers of both sides that engaged each other, with the British side suffering comparatively heavy losses. Then the main body of both fleets came into contact. The German navy soon withdrew from this engagement badly weakened. During the night, it was mainly small units of both sides that were active. The next morning, the German fleet returned to its ports. It had inflicted heavier losses on the British fleet than it had suffered itself, but Britain remained in command of the seas.10

As the German fleet had returned to port before the British fleet, the German Admiralty was able to put out the first official reports of the engagement in the North Sea. A report in the morning edition of the Berliner Tageblatt on 2 June 1916 stated that there had been a "successful naval battle against the main body of the English [sic] fleet".11 German navy command related the scale of the success to the numbers of ships lost by each side.12 Two German ships had been lost and one was missing compared with the loss of at least six British ships.13 Over the subsequent days, the German side gradually admitted the full scale of its losses, which, in total, were still less than the British ones.14 Writing in the evening addition of the Tageblatt on 2 June, the newspaper's naval expert, retired captain-at-sea Lothar Persius (1864–1944) ,15 stressed that the Royal Navy had not only lost important ships, but also "prestige". Even though further German losses had been confirmed, he argued, the excellent performance of German sailors and German technology was undeniable. The German High Seas Fleet had delivered "a painful blow" – though he conceded that the Grand Fleet remained numerically superior to it.16

The German Admiralty and the Berliner Tageblatt – which largely supported the Admiralty's version of the battle – pursued three aims in their representation of the naval battle. Firstly, they sought to protect the reputation of the German navy at home and to justify the many years of naval build-up that had preceded the war. Persius had already declared after the first official report of the battle that its outcome would "prompt the most exuberant joy and satisfaction in Germany".17 The president of the Reichstag, Johannes Kaempf (1842–1918) , stressed in a speech to parliament that "a great and beautiful victory has been achieved by our young navy".18 The foreign edition of the Tageblatt subsequently explicitly stated that the policy of naval build-up had been proven right.19 Secondly, they sought to create or strengthen the impression in neutral countries that, while Germany was not on a par with Britain in terms of naval power, it was nonetheless not at Britain's mercy in this regard, and that Britain's naval dominance was by no means unchallenged.20 After all, Germany was still dependent on neutral shipping companies daring to transport goods for Germany in spite of the British naval blockade. Thirdly, the representation of the battle was intended to sow doubts about the British navy in the enemy camp and among Germany's allies in order to potentially influence the course of the war.

These three aims were also pursued on the British side – albeit with the roles reversed. In the case of the last two aims, those who constructed the media version of the naval battle on the British and German sides went into direct competition with each other. However, because the Grand Fleet returned to port later than the German fleet, the British Admiralty began its efforts about a day after its German counterpart. The first reports appeared in The Times on 3 June. Initially, the reports seemed to confirm the jubilant German version, as the Admiralty conceded that the Grand Fleet had suffered heavy losses. However, the reports also stressed three aspects that were intended to relativise this. Firstly, the conditions in which the naval battle had been fought had greatly favoured the Germans. Secondly, losses had been inflicted on the enemy that were at least as great as those suffered by the British fleet. Thirdly, the German High Seas Fleet had fled shortly after the main body of the Grand Fleet had intervened in the battle.21

The British Admiralty was also supported by journalists in its construction of the battle’s media version. At that, the part played by British journalists in shaping the media event was greater than that played by their German counterparts. The former criticised the state organs more openly. Their reports carried more information that had been acquired by their own research, which formed the basis of their own interpretation of events. In view of the delayed reporting, this was very much welcomed by the Admiralty, which had deliberately loosened censorship to this end.22 Thus, The Times not only supported the reports of the Admiralty with reports and commentary by its own correspondents, but also expanded on those reports. It emphasized that the German navy had only been successful while it had enjoyed a numerical advantage,23 and it stressed that Zeppelins and mine-laying submarines had played an important role in German success. It had not been solely due to skilled seamanship and the quality of the German fleet,24 both of which were excellent on the British side.25 Above all, The Times stressed, the outcome of the naval battle had not changed the overall "naval situation": the blockade remained in place, the Allies were able to move freely on the high seas and Germany would still have to take on the Grand Fleet to change this.26

In this way, the outline of the naval battle as a media event (or media events) was set up. According to the German version, a young navy, which due to shrewd political planning was well trained, excellently equipped and highly motivated, had taken on its superior enemy and had inflicted heavy losses in men, material and prestige on that enemy while suffering only light losses itself. According to the British media event, by contrast, the battle had been a defensive victory for Britain. Thanks to numerous conditions that were in its favour, the German fleet had inflicted heavy damage, but the Royal Navy with its long tradition of naval dominance had put the Germany fleet to flight, had inflicted just as heavy losses on the latter, and had repelled a challenge to Britain's naval supremacy. Over the subsequent days, these interpretations became more fixed, and their reception by target groups at home, in neutral countries, in allied countries and in the enemy country was tested.

For the benefit of the domestic audience, The Times stressed that the losses suffered would only strengthen the resolve of the British people. "It will sting them to fresh exertion, it will dispel much idle and harmful optimism, it will steel their unalterable resolution to win this war or to perish."27 The newspaper regretted that the German side had been able to disseminate its "version of the fighting" in numerous neutral countries, describing that version as "as usual, exaggerated and misleading" and serving "for the moment [to] impress credulous neutrals, and even … to cause temporary discouragement amongst some of our Allies".28 But ultimately, Britain could depend on the ability of allies and neutral countries to judge for themselves, The Times stated.29 After all, the New York Stock Exchange had recovered from the fall in stocks that had occurred after the initial German reports of success30 and the Dutch media were already asking why the supposedly successful German fleet had retreated to its ports.31 On 5 June, The Times reported that the public view in the USA was that "Britannia still rules the waves".32 In allied France, The Times reported, the battle had resulted in the size of the British contribution to the war being publicly recognized for the first time.33

On the German side, Persius argued on the day of the first British statements about the battle that it was to be expected that Great Britain would attempt to hide or relativize its own losses and "to construct" greater losses on the German side.34 Such "Legendenbildungen" (myth making) – as the German Admiralty described it in a further statement35 – was of course hopeless, as "the neutral press" knows "that the German Admiralty usually immediately admits to every loss".36 It was undeniable, according to Persius, that the High Seas Fleet "had succeeded again in delivering a mighty blow to that arrogant phrase 'Britannia rules the waves'".37 The Berliner Tageblatt carried numerous reports from neutral and allied countries that were intended to demonstrate that the version of the naval battle constructed in the German media was the one that corresponded to the naval reality.38 The newspaper quoted from articles, according to which the battle would "have the greatest consequences for global history".39 Swedish newspapers had – according to the Tageblatt – adjudged that the British "control of the seas now appears highly questionable".40 In the case of the British media, on 4 June the Tageblatt cited the Daily News as having supposedly acknowledged the British defeat.41 In response to British accusations that the German side was concealing its own losses,42 Persius stated that "nobody who is able to judge for themselves … is in the slightest doubt that the report of the [German] Admiralty regarding our losses is accurate".43 Even after the German navy had been forced to admit additional losses, which the British side made full use of to attack German credibility,44 Persius remained undeterred. Germany had achieved something great, he insisted. This was confirmed by "newspapers from enemy countries and neutral countries! Nobody can … deny that the battle represents a precious glorious chapter in German naval history".45

The two versions of the naval battle as media events thus stood in direct competition with each other. They were bound up with the hope, which was formulated with the domestic audience in mind, that they could affect the course of the war. Josef Schwab (1865–1942) stressed in the weekly foreign edition of the Berliner Tageblatt on 6 June that the success of the German fleet had illustrated "that it is not possible to defeat the allied Central Powers". The "political significance of our victory" would have to be impressed upon the enemy nations so that they would declare their willingness to sue for peace.46 On the British side, Winston Churchill (1874–1965) viewed the battle as "a definite step towards the attainment of complete victory"47 and a leading article in The Times stated that it had strengthened the resolve of the country to the extent that it would resist the peace negotiations being suggested by neutral countries at the instigation of German agents. "The magnitude of our losses in men and in ships has burnt into us the grim resolve that these losses shall not have been in vain."48

Neither of the two media events was able to win out over the other because, as the navy correspondent of The Times observed on 5 June, "[i]t can surprise nobody if both combatants claim a victory, the Germans because they were not beaten decisively in their first big engagement with the strongest Fleet in the world; and the British because they defeated the object of the enemy and forced him to fly for safety".49 Of course, this did not discourage either side from continuing to write in support of their own media version of the battle. The weekly edition of the Berliner Tageblatt of 14 June ended with a cartoon depicting two sailors in the North Sea. The German sailor with his gun raised shouts triumphantly after the retreating Briton: "'Hey, Englishman, you lost something!' 'What?' 'Naval dominance!'"50

The public controversy regarding the interpretation of the naval battle did not end during the course of the war, but continued in the years afterwards.51 One reason for this is that, ultimately, a case could be made for both versions of the battle. It can be said that two competing media events were constructed over the duration of the war and beyond, which were intended to influence the course of the war itself by motivating the domestic audience and allies, by drawing neutral countries onto one's own side, and by demoralizing the enemy. This approach was not a coincidence. During the course of the war, the British and German armed forces had increasingly attempted to influence the conflict by means of media reporting.52

Media Events in the Media Strategies of the Armed Forces

Prior to the First World War, the idea that human action could be influenced on a large scale with the help of media reporting received particular interest at the news service of the German Imperial Naval Office.5354 Based on experiences in peacetime and inspired by observations from the Russo-Japanese War, the idea was already expressed in January 1905 that in wartime the service should be used "for the publication of war news, war reports, etc., and in so doing potentially exert influence over the war".55 One year later, the German Admiralty adopted this idea and now held the view that in wartime the German navy would need a central office for working with the media, which "in the interests of our own war effort … publishes news in newspapers, … that in the public – specifically abroad – will be advantageous for our cause".56

After the outbreak of war, the German navy started having reports published that suited its purposes from 3 August 1914 onward.57 The army was initially hesitant to follow its lead and viewed the provision of information to the media primarily as a quid pro quo for the cooperation of the media in maintaining secrecy regarding "militarily relevant" sites.58 The British military was similarly reticent to start with.59 However, in both countries the armed forces soon changed their attitude and began to push for media support for the war effort. From the winter of 1914/1915 onward, the German army had accounts of individual combat engagements prepared for the press. In December 1914, the quartermaster general, General Adolf Wild von Hohenborn (1860–1925) , called for reports of heroic deeds, to "honour the heroes, engender pride in their relatives, and provide an incentive to the young units".60 According to General Erich von Falkenhayn (1861–1922) , a Kriegsnachrichtenstelle61 (war news service) should "on the basis of battle reports, present to the public individual, discrete battle operations, while primarily focusing on exceptional deeds by units or individuals".62 In other words, military occurrences were to be transformed into media events to motivate domestic civilian society to support the war effort. This support was considered crucial. In the words of Colonel General Helmuth von Moltke (1848–1916) : "The outcome of the war does not depend on the army alone. The nation itself bears half of the responsibility for the outcome of the war. The attitude that we adopt at home affects the attitude of our soldiers through a million threads."63 These efforts to influence the mood at home were expanded during the course of the war.64 The British military followed the German example closely, and though the media in Britain were allowed greater space for their own initiative, leading representatives of the army such as Field Marshal Douglas Haig (1861–1928) used censorship and personal connections to journalists to turn reports of military developments into media events that suited their purpose.65

Together with domestic audiences, neutral states were also a target of these media events. Here too, it the German armed forces became active first. One of their main aims was to portray their strategy of using submarines against merchant ships as a legitimate reaction to the blockade of Germany.66 In response, the British military, which viewed the use of media coverage in this context as a "fourth weapon",67 presented its own perspective at regular conferences and put out official reports, such as those of Haig.68 The construction of the Battle of Jutland as a media event demonstrates in exemplary fashion how much the armed forces of both sides cared about how neutral states judged their interpretations of military events. It also shows how closely the two combatants observed each other's media coverage.

The naval battle was in fact a pivotal point in the media activities of the armed forces during the war. Under the constant observation of the enemy, this work was increasingly intensified during the second half of the conflict, and it was understood as a means of weakening the enemy, not least in terms of the resolve of its civilian population. Shortly before the engagement between the two battle fleets in the North Sea, the German naval media expert Karl Boy-Ed (1872–1930) had emphasized how important it was "to support the naval war effort through the press whenever possible".69 He was also in favour of the army engaging in such activities because, in his view, the war was increasingly "being one of public opinions" and "deeds alone will not get it done in our time of press dominance!"70 To him, the "deeds", ranging from military operations to German victories, also had to be portrayed in the right way in the media in order to affect the course of the war. In other words, they had to be staged as media events. He was not alone in this view. In early 1918, First Quartermaster-General Erich Ludendorff (1865–1937) stressed that it was the duty of those producing reports for the military office at the department of foreign affairs "to exploit politically in neutral and enemy countries the military successes of German arms by publicising them in words, images, films and oral propaganda".71 For him, the media portrayal of one's own successes was "an aid to achieving victory",72 the aim of which was "to destroy the will of the enemy's home front to continue the war by making correct propagandistic use of our military victories".73 In the strategic thinking of the supreme army command, turning battles into media events was crucial to successfully prosecuting the war in view of the military stalemate at the front. Compared to this position, the British armed forces were more reticent. Nonetheless, they also took an interest in the media portrayal of military engagements and they shared the view that this portrayal could affect the outcome of engagements. For example, Haig was eager to have the Battle of the Somme presented as a success in the media,74 and the taking of Jerusalem in late 1917 was turned into a media event through the careful staging of the entry of the British into the city under General Edmund Allenby (1861–1936) .75 However, on the British side it was primarily politicians and journalists who sought to influence the war by means of skilfully constructed media events. The newspaper owner Lord Beaverbrook (Max Aitken, 1879–1964), who was appointed minister of information during the war, asserted that the media aspect of the war was "not less vital for victory than fleets and armies".76

In spite of the importance that was attributed to the media portrayal of the First World War while the war was ongoing, ultimately it was not decided in the media but by the logistical, numerical and military superiority of the Allies with the assistance of the USA – even if this view was not shared by everyone in the aftermath of the war.

Aftermath of the First World War as a Media Event

After the weapons had (largely) fallen silent and the First World War had ended, there were those who were still convinced that the media aspect had been decisive.77 They included those on the Allied side who were viewed as successful propagandists, and who asserted even outside their own circles that their work had made a vital contribution to the outcome of the war.78 In Germany, right-wing nationalist circles seized on the influence of the media as a way of explaining their own defeat without admitting military inferiority. The ground was already prepared for this interpretation when Moltke declared in 1915 that the domestic population would carry part of the responsibility for the outcome of the war. In November 1918, Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934) carried this interpretation forward by asserting that the enemy had "succeeded in depressing the mood on our side at home and in the army through planned propaganda".79 These were the first building blocks of the Dolchstoßlegende (stab-in-the-back myth) and the central basis of National Socialist enthusiasm for propaganda.80 At the heart of that propaganda was the reinterpretation of the First World War as a conflict that had been decided through the skilful control of the media, or, to put it another way, a retrospective construction of the First World War as a media event.

Hidden Stories in Beaumaris Cemetery

by Bridget Geoghan

This is Bridget’s article on her findings in Beaumaris cemetery. She emphasizes that this is not the churchyard in the centre of the town but the cemetery on the edge. You can find it by taking a left turn after the Gallow’s Point petrol station as you approach the town, then another immediate turn left, and then another one, through the gates.

In her own words, this is how it came about:

“I was asked by the local British Legion guy to research burials /commemorations with military connections in Beaumaris Cemetery.

In rather a nice touch, the Mayor and members of the Town Council visit the graves on Remembrance Sunday each year. We put poppy posies on the graves beforehand.

Bridget Geoghegan”

The Hidden Stories of Beaumaris Cemetery

There are 8 Commonwealth War Graves (marked with an asterisk * in this text). Four men have the typical Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) headstone in either slate or Portland stone; one lies flat on a family grave; four have family headstones. Seven are from the Great War of 1914 – 1918 and one is for WWII of 1939 – 1945.

Most of the others listed here are buried elsewhere, but remembered on their family graves; however there are some whose death was caused by war, but who died too late to be a casualty. All marked by ✿ have poppy posies on Remembrance Sunday (30; 1 grave has 2 commemorations).

Note: the title line for each person is the wording on their headstone.

1 - Elizabeth Lester - widow of the late Rev. Canon Major Lester M.A. R.D.

Elizabeth Lester (née Maddock), her daughter Jessie and son in law Geoffrey Holme; Elizabeth, widow of Thomas Major Lester, Canon of Liverpool Cathedral and founder of Ragged School in Liverpool, mother of eight children, living in Beaumaris at the time of her death.

Her daughter Jessie Holme (née Lester) and Geoffrey Holme, he had been an Architect and Building Contractor in Liverpool, retired to Anglesey; volunteer in local battalion during Great War, contributed to the design of the Memorial Window in church of St Cawrdaf, Llangoed; they were parents of Lt Bertram Lester Holme RWF died on April 25 1916, whilst serving in Mesopotamia.

Kerb grave with cross lying on it - Elizabeth Lester widow of the late Rev. Canon Major Lester M.A. R.D. (Rural Dean) of Liverpool, died June 12th 1925 aged 96 years. Geoffrey Cossett Holme of Liverpool Died May 21st 1945 aged 86 years. Jessie, wife of Geoffrey Holme, died May 26 1957 aged 91 years.

✿ 2 - In Memory of Harold Samuel Peeke Lt.–Col RAMC

Not an official a war casualty; son of Samuel Peeke, commercial traveller and Emily, husband of Mary Ethel; Lieutenant Colonel Royal Army Medical Corps; served in Anglo Boer War, ‘Soudan’ and recalled to the Active List from the Reserve of Officers on 16th March 1915 to run the Liverpool Merchants’ Mobile Hospital (No 6 Red Cross Hospital) in Etaples, France; Mentioned in Despatches, awarded the Order of St John and Silver Badge; not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

Distinctive St John’s Cross on the flat gravestone: In Memory of Harold Samuel Peeke Lt.– Col RAMC. Born Dec 17th 1864 Died Mar 21st 1926. “The Lord preserve us in the number of the faithful“.

✿ 3 - Sacred to the Memory of Pte. John Frederick Thomas (Fred)

John Frederick Thomas, born Beaumaris; son of Thomas and Eliza Frances Emma Thomas of 8 Stanley Street; one of three brothers who served, the others came home; Private 40037

South Wales Borderers 2nd Battalion (previously Royal Welsh Fusiliers); died at Battle of Arras; Beaumaris Cenotaph: J. F. Thomas Pte. R.W.F.

CWGC: Private John Frederick Thomas – Service No 40037 – Died Saturday 19.05.1917 – Age 22 – 2nd Bn. South Wales Borderers – Son of Thomas and E. F. E. Thomas, of 8. Stanley St., Beaumaris, Anglesea. – Commemorated on Arras Memorial, Pas de Calais (no grave).

Commemorated on slate family headstone (crossed rifles and military cap): “Thy Will Be Done” - Sacred to the memory of Pte. John Frederick Thomas (Fred) 2nd Batt. S.W.B., late R.W.F. Killed in action at Monchy-Le-Preux May 19th 1917. Aged 22 Years. Beloved son of Thomas and Emma Thomas, 8 Stanley Street. God grant him Eternal Rest. Also father of the above, Thomas Thomas, Died Dec 21st 1939, Aged 80 years. At rest. Also Eliza Frances Emma. Wife of the above Thomas Thomas. Who died November 28, 1951. Aged 91 years. “Peace, perfect peace.”

* ✿ 4 – In Loving Memory of Robert Vernon Eldest Son of William R and Emily Jones Robert Vernon Jones, eldest son of Alderman William R and Mrs Emily Jones of Cremlyn, (later Tyddyn Fryar), brother W Havard Jones served as Lieutenant in RWF was seriously wounded; educated Beaumaris Grammar School; worked on the family farm near Beaumaris ; joined up 5th August 1914 (war declared on 4th August) Private 301869, 3rd Reserve Cavalry Regiment (previously 3153 Denbigh Yeomanry & 50395 Imperial Camel Corps); served in UK, Egypt and Palestine; died in Aldershot of influenza; age 27; Beaumaris Cenotaph: R. V. Jones Pte. D.H.Y.

CWGC burial in Beaumaris Cemetery, family headstone - marble cross on stepped pedestal with kerb: In Loving Memory of Eliza Maria Williams daughter of the late David & Susannah Williams (?). Martha Emily Jones who died on the 5th September 1933 (?). In Loving Memory of William Jones Born March 18th 1854, Died Jan 2nd 1921. At Rest. In Loving Memory of Robert Vernon, eldest son of William R and Emily Jones, who died on the 29th March 1919, aged 26.

✿ 5 – To the glory of God and in loving memory of Bruce Lindon Haynes Capt. R.A. His grandparents lived at ‘Glanfa’ Beaumaris; born in 1919 to Percy and Alice Maude Haynes; attended Cheltenham College; was an Articled Clerk to become a Member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants; volunteered for the Royal Artillery; killed in action in Tunisia.

CWGC: Bruce Lyndon Haynes - 117515 - Captain 71 Field Regt. Royal Artillery – Died Thursday 22 April 1943 – 24 years old – Steadfast. Greater love hath no man than this. “Floreat Cheltona” - Son of Major Percy Haynes, R.A.P.C., and Alice Maude Haynes – Buried Medjez-el-Bab War Cemetery, Tunisia.

Headstone - a cross on stepped plinth with kerb: In remembrance of my beloved wife Mary Emma Williams died Nov 9th 1915 aged 57 years. Also Lloyd Williams beloved husband of above, died Dec 23rd 1936 aged 78 years. Stone on grave: To the glory of God & in loving memory of Bruce Lindon Haynes Capt. R.A. (Old Cheltonian) killed in action – N. Africa April 22, 1943. Only son of Major P. & A. M. Haynes & grandson of the above. Greater love hath no man.

- ✿ 6 - 68090 Private - Williams - South Wales Borderers

John Williams, South Wales Borderers 53rd Battalion; son of Catherine Parry (previously Williams) and the late John Williams of 2 Castle Row, Beaumaris; a postal worker before joining up; enlisted at Wrexham probably September 1918; died at Kinmel Park Training Camp near Rhyl of pneumonia; Beaumaris Cenotaph: J. Williams Pte. S.W.B.

CWGC burial in Beaumaris Cemetery, slate headstone lies flat on family grave: South Wales Borderers badge - 68090 Private - J. Williams - South Wales Borderers – 19th October 1918. Age 18.

Also commemorated on slate family headstone with kerb: In Loving Memory of Catherine, Beloved Wife of Henry Parry, Bryn Lodge, Beaumaris, who died April 24, 1952, Aged 86 years. Also Son of Above, Pte. J. Williams (S.W.B.) died Oct 9, 1918, Aged 18 years. Also Henry Parry who died March 20, 1963. Aged 92 years.

✿ 7 - In beloved memory of Llewelyn Greenly Jones. Killed in Tunis

A Bangor lad; brought up in Bryn Difyr, Lon Pobty, son to Hector Greenly and Edith Jones of Bangor; husband to Vera Grace of Ewell in Surrey; sales assistant in the Lotus & Delta Shoe Shop, Bangor; signed up with the Welsh Guards before war broke out; to France in 1940, evacuated from Dunkirk; married February 1943; North Africa with Montgomery’s 8th Army; died after being shot by a sniper; commemorated Bangor Cenotaph; not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

CWGC: Llewelyn Greenly Jones – Guardsman 2736546 – Died Friday 08.05.1943 – Aged 23 – 3rd Bn. Welsh Guards – Son of Hector Greenly Jones and Edith Greenly Jones; husband of Vera Grace Jones, of Ewell, Surrey - Buried Enfidaville War Cemetery, Tunis.

Commemorated on slate family headstone (low headstone, decoration of ivy leaves, kerb) - family connection not yet established: Cherished Memories of my beloved husband Stewart Humphrey Owen. Died June 21 1945. Aged 57 years. “Until we meet again Darling.” Also Pansy Isabel Owen, Beloved wife of the above. Died Oct. 9, 1961, Age 65. “They’ve met”. Flower holder: From friends & neighbours of Walton Close. On kerb: In beloved memory of Llewelyn Greenly Jones. Killed in Tunis, May 8 1943. Aged 23. Plaque: Vernon J. H. Dibben – 1932–2001 – At Peace.

- ✿ 8 - 7007 Sapper – V. Hill - Royal Engineers – 9th May 1915

Samuel Vose Hill, 5th Siege Company, Royal Anglesey Royal Engineers; born Manchester; son (only child) of Emily Hill of ‘Brentwood’ Stockport Road, Altrincham, Cheshire and the late Samuel Vose Hill; enlisted Manchester and posted to RARE Depot, Kingsbridge, Llanfaes; one of the Royal Engineers party to repair Bangor Pier after SS Christiana damaged it; died Sunday 9th May 1915 by accidental drowning in a pleasure boat off Gallows Point, Beaumaris; buried about 29th June 1915 with full military honours; age 31; not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

CWGC burial Beaumaris Cemetery, Portland stone headstone (Royal Engineers badge): 7007 Sapper – S. V. Hill - Royal Engineers – 9th May 1915.

- ✿ 9 – 6888 Sapper - Hemingway - Royal Engineers – 9th May 1915, Age 24

Lionel Hemingway, 5th Siege Company, Royal Anglesey Royal Engineers; born Stoke Prior, Bromsgrove, Worcestershire; son of Susan P Hemingway of 21 Prince’s Avenue, Witton, Droitwich Spa, Worcestershire and the late David Hemingway; a skilled art metal worker, trained at the Guild of Applied Arts; enlisted Birmingham and posted to RARE Depot, Kingsbridge, Llanfaes; one of the Royal Engineers party to repair Bangor Pier after SS Christiana loosened from her moorings and rammed it night of 14th December 1914; died Sunday 9th May 1915 by accidental drowning in a pleasure boat off Gallows Point, Beaumaris; age 24; buried 5th June 1915 with full military honours; commemorated St Michael’s Church War Memorial, Stoke Prior, Worcestershire; not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

CWGC burial Beaumaris Cemetery, slate headstone (Royal Engineers badge): 6888 Sapper - L. Hemingway - Royal Engineers – 9th May 1915 age 24.

✿ 10 - In Loving Memory of my dear father Francis Williams

Not an official war casualty; merchant seaman, son of John and Ann J Williams of Steeple Lane, husband of Nellie Evelyn; lived 37 Church Street; Ordinary Seaman on SS Greypoint, accidentally drowned in Trafalgar Dock, Liverpool (described as a ‘domestic gardener’ at inquest); Beaumaris Cenotaph: F. Williams M.N.

Burial, slate family headstone (anchors in top corners) - In Loving Memory of my dear father Francis Williams. Died Oct. 14, 1939, Aged 35. Also Nellie Evelyn wife of the above died Oct. 1967. Interred in Oxford. “Resting where no shadows fall.” John Goodman Williams 1932 – 2016 A Beaumaris boy, loving father & grandfather. Sailed the world to return home.

✿ 11 - 3121432 Aircraftman 2nd Class - Harold E. Jones - Royal Air Force

A national serviceman, recruited in Padgate, Warrington May 1949; possibly an aircraft assistant whose duties would include looking after squadron stores, aircraft cleaning, towing aircraft in and out of hangars; died just before demob date; in 2019 a poppy cross on the grave: ‘Eddie Jones’.

CWGC burial in Beaumaris Cemetery, Portland stone headstone: RAF badge - 3121432 Aircraftman 2nd Cl. - Harold E. Jones – Royal Air Force – 7th April 1951 - Age 20 – In Loving Memory of my dear brother. Rest in peace.

- ✿ 12 - Also their beloved Grandson, L.A.C. Evan John Kite, Royal Air Force V.R. Evan John Kite, son John Edward and Elizabeth Kite; educated Beaumaris Grammar School; leading aircraftman 983012, RAF Volunteer Reserve, 76 Squadron (Bomber Command) based at Linton-on-Ouse, flying Handley Page Halifax aircraft; son of John Edward and Elizabeth Kite of Beaumaris; ‘died on active service’; Beaumaris Cenotaph: J. Kite L.A.C. R.A.F.

CWGC burial in Beaumaris Cemetery; slate family headstone with Handley Page Halifax in roundel, ivy leaves on side pillars: Treasured Memories of Elizabeth Williams, Beloved wife of Hugh Williams, departed this life Oct. 7, 1937, Aged 82 years.

Also Hugh Williams, departed this life July 27, 1940. Aged 83 years. Also their beloved Grandson, L.A.C. Evan John Kite, Royal Air Force V.R. Lost his life on war operation, Serving his King and Country, April 28 1943, Aged 23 Years. At Rest.

Note: John Hudson Staples RAFVR has Mosquito aeroplane on his headstone at St Iestyn, Llanddona.

✿ 13 – Er Gof Annwyl am Robert . . . Hefyd y dyweded C. William Jones, a fu farw chwef. 25. 1940, yn 45 mlwydd oed.

Brought up in Holyhead; career Merchant Seaman before WWI; served with Royal Anglesey Royal Engineers during WWI; 1917 married Selina Roberts, a Beaumaris girl from Felin Cichle (sister of David Roberts who also served with the Royal Engineers and John Griffith Roberts, served with the RWF 8th Battalion, killed in action 15 Feb 1917 at Mesopotamia); after 1918 with London and North Western Railway - Royal Mail Ships; John’s burial record states death was on board R.M.S. Cambria, Holyhead (Royal Mail Ship); children had been living with grandparents Grace and William, at 13 Stanley Street, since Selena’s death in 1927

✿ 14 - And their son Ft. Lt. Emlyn Parry reported missing over Germany.

Born in 1917; son of Henry and Martha Parry; educated Beaumaris Grammar School; joined up as ground crew, transferred to air crew; part of Battle of Britain and Bomber Command; lost over Germany on a mission to bomb Krupps factory in Essen, flew in Halifax aircraft; Beaumaris Cenotaph E. Parry P.O. R.A.F.

CWGC: Flying Officer (Wireless Operator/Air Gunner) Service No 137569 – Died Friday 28.05.1943 – Aged 26 – 10 Sqdn. Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve - Son of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Parry of Beaumaris Anglesey - Buried Reichswald Forest War Cemetery.

Commemorated on family headstone (flat, polished granite): In Memory of Martha Parry, 1883 – 1949 and her beloved husband Henry Parry 1880 – 1960. Also their daughter Elizabeth Mary Parry 1911 – 1929 and their son Ft. Lt. Emlyn Parry reported missing over Germany 1909 - 1941. Leslie Schofield grandson died 1953 aged 2 days. (Note: dates as seen.)

✿ 15 – Also Hugh their youngest son who fell in action at Suvla Bay

Youngest of five and a professional soldier, son of a professional soldier; father, Staff Sergeant with the Royal Anglesey Royal Engineers, died young; mother, Eliza, later listed as victualler, then ran a lodging house (one child born Chelsea Barracks, one in Tower of London); Hugh born Beaumaris, in Guards Barracks, London in census 1901 – served in South Africa 2nd Boer War

CWGC: Serjeant Hugh Hughes - Service No 3/9199 – West Yorkshire (Prince of Wales’s Own) 9th Bn. - Died 9th August 1915 – Commemorated Helles Memorial

Commemorated on the family grave, rough granite kerb grave; cross and plaque lie on top: In Loving Memory of Father and Mother, Robert Hughes Sergt. R.A.R.E. died Dec 21 1897, aged 57 years and Eliza his wife, died April 9 1922 aged 80 years. Also Eliza Anne their youngest daughter, died Sept. 21St 1931 aged 50 years; Also Margaret Elizabeth May, died Dec 26, 1948. Also Hugh their youngest son who fell in action at Suvla Bay with the 9th West Yorkshire Regt. August 9th 1915, aged 37 years.

Plaque on grave: Also in loving memory of William Hugh Hughes, died April 14 1977 aged 76 years. Cross on grave: “Thy will be done”.

✿ 16 - In loving memory of . . . and Emma Henderson, Legion d‘Honneur, Medaille Militaire (née Tattersall) his wife

Not war casualties: grave for Emma Elizabeth Tattersall, her sons Charles Edward Owen and Hugh Herbert, others are commemorations. Emma Lilian Tattersall, active in the French Resistance with her husband Mario Nikis; both caught, interrogated and sent to concentration camp, he died on the way there; she survived, later remarried (Charles Henderson) and continued to live in France.

Commemorated on family grave (cross with scroll, rough hewn plinth with new slate inscription and kerb): In memoriam - Charles Edward Owen youngest son of William Alfred Tattersall M.A. Vicar of Oxton. And Emma Elizabeth his wife Died March 5, 1888, Aged 20. Also of the above Emma Elizabeth Tattersall died March 11, 1912. Aged 83. Also of their son Hugh Herbert Tattersall died April 24, 1933. Aged 73. (and plaque on the grave) In loving memory of Lilian Elizabeth Tattersall, Born 21 Jan. 1874, died 9 March 1966. Vera Toler, Born 1 April 1898, died 19 Jan. 1989, daughter of Hugh Herbert Tattersall. Charles James Henderson K.B.E. Born 9 Nov. 1882, died 31 May 1974, son of Henry Henderson. And Emma Henderson Legion d’Honneur, Medaille Militaire (née Tattersall) his wife, Born 9 March 1905, Died 3 March 2004, daughter of Hugh Herbert Tattersall.

- - Sacred to the Memory of John Jones, Father of John Jones, Governor of the Anglesey County Gaol who departed this life on the 16th day of January 1864. Aged 83 (This was the first internment in this consecrated ground.)

Not a war casualty; had served in British Navy, gunner at the Battle of Copenhagan (1807); first cousin of father of Lieut Col Morris, 17th Lancers, survived ‘The Charge’ at Balaclava

- - In Memory of Richard Norman, formerly Captain 7th Royal Fusiliers. Died 18th March 1886 aged 78. He walked with God and he was not for God took him. Maria the wife of Richard Norman late of Tan-y-Coed Anglesey - Died November (?)

Neither are war casualties; he was son of Richard Norman of Melton Mowbray and Rt Hon Lady Elizabeth Isabella Manners, daughter of 4th Duke of Rutland; married first to Maria (died 1862, burial registered Llandegfan) and secondly to Mary Anne Sandys of Craig yr Halen, Menai Bridge

✿ 19 - In memory of my beloved husband Evan P. Thomas (late Canadian Infantry) Not an official war casualty; Evan Pritchard Thomas; son of Evan and Catherine (née Pritchard) Thomas, brother of W Eric Thomas, husband of Hannah Mary; educated at Beaumaris Grammar School; served for two years with Royal Welsh Fusiliers; 1912 emigrated to Winnipeg, Canada to work as a carpenter; October 1914 volunteered for service in Canadian Infantry; badly injured, evacuated back to Canada March 1919, discharged as unfit October 1919; returned to Beaumaris to work as a building contractor; married 1921; died November 1924 from the effects of his wounds; not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

Buried in family grave (rough granite cross on stepped pedestal, with kerb): In memory of my beloved husband Evan P. Thomas (late Canadian Infantry) who died Nov 16 1924 from wounds received in the Great War 1914-18, aged 38 years. Also his wife Hannah Mary Thomas died Feb 20th 1975 aged 88 years.

✿ 20 - And their daughter Menna Lloyd Jones 1905 – 1970, widow of Capt. Morris Jones M.N. 1900–1941

Not an official war casualty; Master Morris Jones, born Penrhyndeudraeth; husband to Menna of Orwell House; Captain of Merchant Navy vessel SS Colon; accidentally drowned Tuesday 22.03.1941, age 41; buried Ismailia War Cemetery, Egypt; Beaumaris Cenotaph: M. Jones Captain M.N.

Commemorated on slate family grave (simple, clear design): In memory of Amelia Lloyd Evans 1871 – 1936 widow of David Lloyd Evans 1861 – 1912 and their daughter Menna Lloyd Evans 1905 – 1970 widow of Capt. Morris Jones M.N. 1900 – 1941.

21 – Long: 30 49’ 2” W – Benarth Hall – Lat: 530 16’ 18” N - Woodgarth - May Tattersall 1940 - Thomas Frederick Tattersall 1943 (sundial style headstone)

Neither are war casualties; Thomas Tattersall and his wife, Helen May born in Pernambuco, Brazil; for many years lived at Benarth Hall, Conwy Valley (Longitude 30 49’ 12” W, Latitude 530 16’ 18”) before moving to ‘Woodgarth’ in Beaumaris (now Ael y Bryn); he was a cotton trader, vice-chairman Williams Deacons Bank, High Sheriff of Carnarvonshire 1920, Mayor of Beaumaris 1942.

✿ 22 - In Loving Memory of John Henry Sloman

Not an official war casualty; son of Francis Sloman and Ellen; first marriage 1909 to Pauline Woollock (she died 1910; baby survived, was brought up by his parents); husband to Olive Mary (née Roberts) of Ogwen View; Sapper RARE, at Kingsbridge Depot, Llanfaes; February 1917 was acting as bombing Instructor when a grenade accident caused him to be medically unfit for the front line; not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

Buried in family grave (white marble cross on stepped pedestal, and kerb): In Loving Memory of John Henry Sloman who died January 21st 1922, aged 35 years “We cannot with our loved ones be, But trust them Father unto thee”. Tablet on grave: Also his dear wife Olive Mary Sloman Died Nov 29, 1971, Aged 80 “Come home to eternal rest”.

✿ 23 - William George Owen . . . Also their youngest son Donald Uvedale Owen

Family lived at Plas Coch Terrace Beaumaris; attended the Grammar School; trained in medicine at Liverpool University; worked as surgeon at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, and Royal Southern Hospital (specialised in heart disease); was in Territorial Army, called up in 1939 and sent to Egypt in charge of a general hospital; developed aplastic anaemia, sent to Johannesburg for treatment which continued till his death in 1943; not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

CWGC: Donald Uvedale Owen – Major 75838 Royal Army Medical Corps – Died 7 December 1943 - Age 43 – Buried at Johannesburg (West Park) Cemetery, South Africa - Mentioned in Despatches – Son of the Revd. William George Owen and Mary Ellen Owen, of Liverpool, England M.D., F.R.C.P., D.T.M.

William George Owen, for 47 years English Presbyterian Minister, born 1841, Died 1913. Mary Ellen Owen, widow of Rev W. G. Owen – died 7 Nov 1947 age 85 years. Also their youngest son Donald Uvedale Owen M.D.D.T.(?) M.I.F.R.(?) C.P.(?) died on active service December 7 1943, aged 43 years. Buried at West Park Cemetery Johannesburg.

✿ 24 - Hefyd, er gof am eu meibion Robert, R.W.F. a gwympod yn y Rhyfel Mawr

Robert Jones, son of Mary and Richard Jones of 18 Wexham Street; worked as a labourer; Private 24719, 14th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers; killed in action, battle of Ypres; Beaumaris Cenotaph: R. Jones Pte R.W.F.

CWGC: Robert Jones, Private 24719, 14th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers - Died 5th October 1916, age 21 - Son of Richard and Mary Jones of 18 Wexham Street, Beaumaris, Anglesey - “Hwn o’i wirfodd a ymroddodd ei hunan, 2 Chron. 17. 6” (Who willingly offered himself) - Buried at Essex Farm Cemetery, Belgium.

Commemorated on slate family headstone grave (joined hands): Er Gof Annwyl am Mary Priod Richard Jones, 18 Wexham St. Beaumaris bu farw Tachw. 1939, yn 66 mlwydd oed. Hefyd, er gof am eu meibion Robert, R.W.F. a gwympodd yn y Rhyfel Mawr, Hud. 5. 1916, yn 21 mlwydd oed. Edward a gyfarfu a damwain angeuol un Ffrainc, Mawrth, 18. 1940, yn 40 mlwydd oed. A gladdwyd yn Warloy, Baillon. Hefyd y dywededig, Richard Jones, bu farw Tach. 13. 1944, yn 87 mlwydd oedd.

And his brother - Edward a gyfarfu a damwain angeuol un Ffrainc, Mawrth, 18. 1940, yn 40 mlwydd oed - Edward Jones - not a war casualty; a civilian who worked for the Imperial War Graves Commission; married to a French national; thought to have died in a car accident; buried in Warloy Baillon Cemetery, France; commemorated on his parents’ grave (see above); not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

- ✿ 25 - Er Gof Serchog am Ellis, Anwyl Fab Robert ac Esther Jones

Ellis Jones, Driver 1855887 R.E.N.D. Royal Engineers; son of Robert Jones and his wife Esther of Henllys Lodge, Beaumaris; born Gyffin, Conway; a career soldier; died at Aldershot Monday 21st March 1921, age 21; not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

CWGC burial in Beaumaris Cemetery, private headstone in slate (palm frond): Er Gof Serchog am Ellis, Anwyl Fab Robert ac Esther Jones, Henllys Lodge, Beaumaris. A Fu Farw Mawrth 21, 1921.Yn 21 Mlwydd Oed. “Fel blodauyn y daw allan, An y torrir ef ymaith. Efe a cilia fel cysgod, ac nisaif .” Hefyd y diwydedig Robert Jones, A fu farw Hydref 17. 1941. Yn 52 mlwydd oed. Hefyd y dywededig Esther Jones, A fu farw Mehfin 11, 1946. Yn 70 Mlwydd Oed. “Gorffwyso Maent Mewn Hedd”.

- ✿ 26 - 3009 Private – Owen – Royal Welch Fusiliers – 8th December 1920

Thomas Owen; Private 32082 Royal Defence Corps (previously Private 3009 Royal Welsh Fusiliers), possibly wounded or gassed on active service then transferred to ‘Home Service’; age 59; family resident at 22 New Street, Beaumaris; died Wednesday 8th December 1920; not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

CWGC burial in Beaumaris Cemetery, slate headstone: Royal Welsh Fusiliers badge - 3009 Private – T. Owen – Royal Welch Fusiliers – 8th December 1920.

✿ 27 - Also, in loving memory of Harry, son of the above named, who was killed in France

Henry (Harry) Williams, son of William and Jane Williams; served with the Australian Imperial Force; had probably emigrated to Adelaide in 1898 where he worked as a labourer; signed up in December 1916; appears to have had poor health; died of wounds received in action; records show a burial in France, since lost; Beaumaris Cenotaph: H. Williams Pte. Aus Imp. Forces.

CWGC: Private Henry Williams – Service Number 7313 – died Wednesday 18.09.1918 – 19th Bn. Australian Infantry, A.I.F. – Commemorated Villers-Bretonneux Memorial (no grave).

Commemorated on slate family headstone (weeping palm): In Memory of William Williams, mariner, died March 3rd 1885 aged 29 years “Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord: for they rest from their labours” also William, son of the above died 15th Aug. 1883. Aged 16 months. Also of Jane, wife of the above died 17th October 1885 aged 34 years. Also, in loving memory of Harry, son of the above named, who was killed in France, when serving in the A.I.F. September 18, 1918. Aged 38 years. And was interred at the Military Cemetery, Jeancourt.

✿ 28 - In loving memory of Henry Eardley 6th R.W.F. Killed in action at the Dardanelles

Brought up in Menai Bridge, lived in Beaumaris after his marriage to Martha; enlisted in Caernarfon 1st /6th Carnarvonshire & Anglesey Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers; landed Gallipoli 8th August 1915, killed in action on the 19th; St Tysilio Cenotaph; Beaumaris Cenotaph: H. Eardley Pte. R.W.F.

CWGC: Private Henry Eardley – Service Number 2893 – Died Thursday 19.08.1915 – Aged 34 – 1st/6th Bn. Royal Welsh Fusiliers – Husband of Martha Eardley, of 19 Stanley St., Beaumaris, Anglesea; Commemorated Helles Memorial (no grave).

Commemorated on slate family headstone (shield flanked by palm fronds, clasped hands): In loving memory of Henry Eardley 6th R.W.F. Killed in action at the Dardanelles Aug 19th 1915. Aged 34 years. Pan clywodd udcorn trwy y tir, Yn calw’r dewr i’r gad; Brysiodd y ymladnodd dros y cwir; Bu farw dros ei wlad; Pe buasai human canddo’n not; Gallasai fod yn fwy; Ond gwell oedd marw’n mhell, Dros cartref, gwlad, a duw. Also children of the above Willie died May 16th 1905 aged 3 years, Henry died July 5th 1905 aged 9 weeks also Martha Jane Eardley died April 11 1955 aged 74 years.

✿ 29 - In memory of my beloved husband Hugh Rowlands D.S.O. M.C.

Not an official war casualty; Hugh Rowlands, born Beaumaris; head teacher at Llaniestyn Council School, Lleyn, Carnarvonshire; enlisted as Private 17139, 13th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers; promoted 2nd Lieutenant 7th Battalion RWF; later attached to the London Regiment, then transferred to the London Regiment; awarded Distinguished Service Order,

Military Cross and Bar, Mentioned in Despatches; left as Captain and Company Commander 1/2nd Battalion London Regiment; returned to teaching; 1939 returned to live at Manora, Beaumaris. Not on Beaumaris Cenotaph.

Buried in family grave (light grey, rough granite, with low headstone and kerb): In memory of my beloved husband Hugh Rowlands D.S.O. M.C. of this town, died May 16, 1940, aged 56. The path of glory leads but to the grave. Also his loving wife Jeannie M. Rowlands. Died Aug. 28, 1973.

* ✿ 30 - John Newton Williams, Cpl 2/6 R.W.F. AND Hugh 16th R.W.F.

John Newton Williams, corporal 266790 Depot, Royal Welsh Fusiliers; eldest son of the late Peter and Anne Williams of 27 Castle Street, Beaumaris; educated Beaumaris Grammar School; worked for National Provincial Bank, latterly in Wolverhampton; died of pneumonia at Blackrock Military Hospital, Dublin, following operations on his leg; Beaumaris Cenotaph: J. N. Williams C.Q.M.S. R.W.F.

CWGC burial in Beaumaris Cemetery, private headstone (white marble, distinctive pink stain, with kerb and chain) - In Loving Memory of Peter Williams 27 Castle St. Beaumaris, who departed this life January 27th 1903, aged 55 years. “In the midst of life we are in death”. “And as thy servant was busy here and there, he was gone”. Also Margaret Beatrice, infant daughter of the above named (Peter) and Anne Williams, who departed this life Oct 29th 1902. Also, John Newton, Cpl 2/6 R.W.F. eldest son of the above who died at Blackrock Military Hospital, April 19th 1919, aged 28 years. In Loving Memory of Hugh 16th R.W.F., 2nd son of the above who fell in action, near Mametz Wood, France, July 10th 1916, aged 24 years. “Thy will be done.” Also, Anne beloved wife of the above named Peter Williams, died on the 28th day of June 1938, aged 75 years.

✿ And his brother - Hugh 16th R.W.F.

William Hugh Williams, Acting Lance Corporal 21523, 16th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers; second son of Peter and Anne Williams of 27 Castle Street (7 children lived, 6 boys); educated Beaumaris Grammar School; worked as a tailor in Amlwch and London; killed in action at Mametz Wood in France; Llangoed War Memorial, Beaumaris Cenotaph:

W. H. Williams L.Cpl. R.W.F.

CWGC William Hugh Williams - Lance Corporal - Service No: 21523 - Date of Death: Tuesday 11.07.1916 - Royal Welsh Fusiliers 16th Bn. - Commemorated Thiepval Memorial, France (no grave).

✿ 31 - In Loving Memory of Percy 13th R.W.F.

Born Beaumaris 1894; son of Edwin and Elizabeth Williams of the Bulls Head Inn; educated Beaumaris Grammar school; intended to become an electrical engineer, meanwhile was working in local ironmongery business; volunteered for service, killed in action at Mametz Wood; Beaumaris Cenotaph: P. Williams Pte. R.W.F.

CWGC: Private P. Williams – Service Number 17370 – Died Monday 10.07.1916 – Aged 21 – 13th Bn. Royal Welsh Fusiliers – Son of Edwin and Elizabeth E. Williams, of 36, Castle St., Beaumaris, Anglesey – Buried Dantzig Alley British Cemetery, Mametz.

Commemorated family headstone (simple cross on stepped pedestal): In loving memory of Edwin Williams who departed this life June 21st 1898 aged 38 years. Also Elizabeth his beloved wife who departed this life May 2nd 1928 aged 65 years. Nora Jones – died Feb 18, 1955 – Aged 58 years. In loving memory of Percy 13th R.W.F. the only son of Edwin and E. Williams, who fell in action near Mametz Wood, France.

✿ 32 - Also, in loving memory of John, his beloved son, Tel. R.N.V.R. H.M.S. Ermine

John Parry, born April 1893, a Beaumaris lad; son of John and Annie Parry; 1901 the family lived at 12 Town’s End, in 1911 at Glandon; a Grocer’s assistant/traveller; joined RNVR July 1915; rated telegraphist October 1916; killed in action, HMS Ermine sank after contact with a mine, close to Stavros in Greece; commemorated Plymouth Naval Memorial, Devon; Beaumaris Cenotaph: J. Parry Telt. R.N.V.R.

CWGC: John Parry Telegraphist - Service Number Mersey Z/541 – Died Monday 02.08.1917

– Aged 24 – M.F.A. “Ermine” – Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve – Son of John and Annie Parry, of 1, Alma St., Beaumaris, Anglesey – Commemorated Plymouth Naval Memorial (no grave).

Commemorated on family headstone (IHS design): In Memory of Mary the beloved wife of John Parry 4 West End, Beaumaris, who died May 14th 1890, Aged 60 years. Also John Parry, son of the above who died June 27th 1930 Aged 57 years. Also, in loving memory of John, his beloved son, Tel. R.N.V.R. H.M.S. Ermine who fell in action in Aegean Sea August 2nd 1917, Aged 24 years “Ai Hun Mor Dawel yw”. Also Ann Parry, who died Oct 17th 1950 aged 84 years.

✿ 33 - In loving Memory of Lieut. A. Trevor Williams of the R.W.F. attached R.F.C.

Born Liverpool, mother had been brought up at Olinda, Beaumaris; he attended Liverpool College and was studying medicine at Liverpool University when he signed up in the RWF, November 1916; transferred to Royal Flying Corps; killed in action; buried Lapugnoy Military Cemetery; Beaumaris Cenotaph: A. T. Williams 2nd Lieut. R.E.C.

CWGC: Arthur Trevor Williams - Second Lieutenant - Died: Tuesday 4 September 1917 - Age: 21 – 25th Sqdn. Royal Flying Corps & 15th Bn. Royal Welsh Fusiliers - Son of Henry E. and Margaret A. Williams, of 94, Anfield Rd., Liverpool – Buried Lapugnoy Military Cemetery, Pas de Calais.

Commemorated on family headstone (stone carved like rustic wooden logs): Beaumaris Cemetery, Family Grave: Er serchog gofadwriaeth am Thomas Hughes Olinda. Yr hwn a hunodd Ionawr 28ain 1908 yn 75 mlwydd oed hefyd Thomas Henry Williams wyr yr uchod yr hwn a hunod Chwefror 20fed 1862 yn 13 mis oed. In loving memory of Lieut. A. Trevor Williams of the R.W.F. attached R.F.C. The only beloved son of A. E. & M. A. Williams of Anfield Rd. Liverpool & Olinda, Beaumaris, who fell in action at Lens, France September 24th 1917 aged 21 years. He gave his life for his country. Also the above named H. E. Williams who died Nov 2 1929, aged 76 years (poem in Welsh, illegible) Also the above named M. A. Williams who died June 18, 1950 aged 90 years.

34 - Anne Thomas. Born May 1 1826. Died January 5 1892 - Also in Loving Memory of her son John Lloyd Thomas, Deputy Surgeon General, Royal Navy. Born 3rd September 1856, died 8th June 1913. Imbued with the high (?) traditions of the Service to which he belonged, Skilled in (?) and faithful to his duty, He served his country well in many lands. He was a man of singular character, a good man, a loyal friend and a trusty counsellor in time of trouble.

John Lloyd Thomas, son of a Beaumaris butcher; career Royal Navy Surgeon who rose to be Deputy Surgeon General; news in the local paper that he was serving on the ‘Temeraire’ in 1886, the Royal Navy’s third vessel of that name; died at 97 Canning Street, Liverpool at the age of 56.

✿ 35 - Also, in loving memory of W. Eric Thomas Sec. Lieut M.G.C. who fell in the Great War

William Eric Thomas, born Beaumaris 1897; son of Evan and Catherine (née Pritchard) Thomas of ‘Angorfa’ 5 Raglan Street, brother of Evan Pritchard Thomas; educated Beaumaris Grammar School; worked in coal exporter’s office in Cardiff; served as Private 16191 13th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers; commissioned Second Lieutenant May 1916, 20th Battalion RWF, transferred to Machine Gun Corps; missing, killed in action; Beaumaris Cenotaph: W. F. Thomas 2nd Lieut. Machine Gun Corps.

CWGC: William Eric Thomas – Second Lieutenant – 118th Coy. Machine Gun Corps (Infantry) - Died Tuesday 31st July 1917 – Age 20 – Son of the late Evan and Catherine Thomas of 5 Raglan St., Beaumaris, Anglesey; Commemorated Menin Gate, Ypres (no grave).

Commemorated on family flat headstone (slate, lettering only): In loving memory of Eunice Mary, daughter of Evan and Catherine Thomas, Angorfa, Beaumaris. Died February 27th 1896. Aged 2½ years. “For of such is the Kingdom of God” And, in loving memory of the above named Evan Thomas, late borough surveyor. died January 25th 1913, aged 63 years. “With Christ which is far better”. Also, in loving memory of W. Eric Thomas, Sec. Lieut. M.G.C. who fell in the Great War July 31st 1917, aged 20 years. Also, in loving memory of Catherine, beloved wife of the above named Evan Thomas who passed away September 6th 1921, aged 63 years. “At rest”.

✿ 36 - Dr Jim Davies O.B.E. 1923 - 2007

Born Pembrokeshire, served with the Royal Air force Volunteer Reserve, 8th man on a 7 crew Lancaster, he carried specialist equipment to block radar from German HQ to aircraft – an inexact science; plane shot down over Netherlands, passed along the line of resistance workers until betrayed, imprisoned in Antwerp then to Prisoner of War Camp, liberated by Russians and home after war; had been deputy Director of Education in Montgomeryshire, retired as Principal of the Normal College, Bangor (now part of the University); Chairman of NSPCC Cymru, committee to raise money for a CT Scanner at Ysbyty Gwynedd and other projects.

Slate headstone with (deliberately) chipped corner: Dr. Jim Davies O.B.E. - 1923 – 2007 - Bewydrodd yn ddewr - Dros Ryddid - Dros Addysg - Dros Blant - Dros Elusen.

✿ 37 – Darren Amos Charlton. Aged 19 years.

Member of Beaumaris Lifeboat Crew; two trips as crew on supply ship to Antarctic Station; he won a design award with his design of the anchor now on his headstone; son of Shirley and Keith Charlton; brother of Abigail and Robert; grandson of Amelia and Ethel. A Beaumaris lad who had had been educated locally; he was crew on the Beaumaris Lifeboat from the age of 17; also crewed on British Survey Antarctic supply ships; his death was accidental.

Black granite headstone showing a lifeboat as it launches: Darren Amos Charlton – Aged 19 years. – 16th October 1970 – 26th April 1990. – Who sailed away to spread his love – Chosen for God’s voyage in heaven above – Everloving son of Shirley and Keith – Beloved brother of Abigail and Robert – Treasured grandson of Amelia and Ethel – Always thoughtful loving and kind – Memories to us all you’ve left behind – Broken hearts can never heal – You will God know how we all feel.

Compiled from the Cymdeithas Hanes Teuluoedd, Gwynedd Family History Society - Memorial Inscriptions

Researched and compiled by Bridget Geoghegan to the memory of John Reilly, RSM 4th Hussars at the Battle of Balaclava; Lt 8th Hussars at the Battle of Gwalior; killed in action 21st June 1858.