War in Peace

Robert Gerwarth and John Horne

Oxford University Press 2010

This book stems from an academic symposium on paramilitary violence in the period from before WWI to the 1917 Russian revolution and into the 1920s. Each chapter is written by a different author, some from the countries concerned. Robert Gerwarth is professor of Modern History at University College Dublin and John Horne is now the emeritus professor of Modern European History at Trinity College Dublin. The location of their alma mater means a wider viewpoint than is often the case with historians based elsewhere. For the record, Robert is German and John is English.

Paramilitary violence was an important aspect of the clashes unleashed by class revolution Russia in 1917. It lead to the counter revolutions in central and Eastern Europe, including Finland and Italy, which in the name of order and authority reacted against a mythic version of the Bolshevik class violence – a case of getting your retaliation in first, if you will. It also helped to shape the struggles over borders and ethnicity in the new states that replaces the multi-ethnic empires of Russia, Austro-Hungary and the Ottomans. It was prominent on all sides in the Irish War of Independence. Paramilitary violence was charged with political significance and acquired a long-lasting symbolism and influence. Various of the movements in World War Two can trace their origins to this period. One thinks of, for example, the Nazis in Germany, the Fascists in Italy, the Ustase, IMRO and Cetniks in Yugoslavia, the communist groups in many countries, and other quasi-fascist groups in, eg, Latvia. Being a civilian minding your own business was a very hazardous, and often fatal, existence in any country where any of these groups operated. As with any civil war situation, the picture is often a complex one of competing groups with an ideology of sort, local warlords and criminals. Two interesting examples where paramilitary violence did not occur on any major scale were mainland Britain and France.

Perhaps two of the most interesting chapters for those interested in WWI are those by John Paul Newman on the Balkans in the 1912-1923 period, and Ugur Umit Ungor on paramilitary violence in the collapsing Ottoman Empire.

The Balkans – where WWI started

Newman’s chapter on the Balkans starts with the history of the region in the 19th century and the struggles by various groups against the Ottomans, as of course this area was part of the Ottoman Empire. These groups emerged with an increasing awareness of national identity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Large paramilitary bands with coherent political goals and official support originated from the early 20th century. They were in conflict with the Ottomans and with each other, more so after the Ottomans were expelled. Both Serbia and Bulgaria used existing paramilitary groups in the first Balkan War. The period between the end of the Second Balkan War and the start of WWI, 1912-1914, was marked by attacks on civilian populations, and each other, by armed bands representing a national cause. This was easier, if that is the right word, because the overarching authority of the Ottomans had been removed. The Kingdom of Serbia was the clear winner in the Balkan Wars. It saw as further targets for its nationalist dream the Hapsburg states of Bosnia and Herzogovina and, in the north, the lands of the Vojvodina (which indeed is part of modern Serbia today). However, Serbia was in no fit condition after two Balkan wars to engage in a struggle with anybody, much less the Hapsburg state. Nevertheless, Serbian nationalist elements both inside and outside the state sought to engage the oppressive colonist of Serbian populated lands, the Hapsburgs. Thus, the two years leading up to WWI were marked by a number of failed assassination attempts on Hapsburg officials and dignitaries carried out by members of the South Slav youth. The assassination of Franz Ferdinand and his wife by a Serb schoolboy was very nearly yet another incompetent assassination attempt on Austro-Hungarian officialdom.

Thus, WWI for the nationalist groups in the Balkans became synonymous with the struggle to rid themselves of the Austro-Hungarians and their central power allies, the Bulgarians. (There was a significant ethnic Bulgarian population in the Balkans at the time, outside the borders of modern Bulgaria).

Yugoslavia (“the land of the southern Slavs”) was created after WWI as an amalgam of the various ethnic groups and religions within the Balkans. The southern portion would be contested after WWI as it had been before WWI by the paramilitary groups (that is Macedonia, Kosovo and Northern Albania. Bulgaria experienced major upheaval. It had been on the side of the Central Powers and lost territory as a result of the Treaty of Neuilly. Thus, from the spring of 1920 the paramilitaries of IMRO crossed the border from Bulgaria to carry out attacks on Yugoslav civilians and gendarmes, in territory which Bulgarians regarded as theirs. The Bulgarian Prime Minister Stamboliski who had sought to relinquish claims on Macedonia territory and make the country part of the European status quo was kidnapped, tortured and murdered by IMRO in 1923.

Serbia, now part of Yugoslavia, used its army and paramilitaries to tackle IMRO incursions into Yugoslavia and fight Albanian guerrilla bands, Kacaks, in Kosovo and Northern Albania and “punish” anyone they did not happen to like. Macedonia was declared to be part of Serbia. A process of colonisation commenced with Serbs being encouraged to move to the area, and the suppression of all Bulgarian institutions.

In that part of the new Yugoslavia comprising the Adriatic coast, the Italian- Yugoslav border and the central European lands of Croatia and Slovenia, matters were complicated by Italy intermeddling and arming paramilitary groups. Italy had been promised by the Allies during WWI that it would get Dalmatia in the break-up of Austro-Hungary, but the Allies went back on their promise when they created Yugoslavia. So, Italy has a grudge with the new Yugoslav state. Typical of the disintegration of Austro-Hungary were the “green cadres” that were active in Croatia and Slovenia. These were Hapsburg deserters, draft dodgers and returned PoWs.

The Croat legion was a group of ex Hapsburg army officers who sought to reverse the territorial changes of the Paris treaties and take Croatia out of the Yugoslav state. Their most important sponsor was Italy which pursued a double move. On one hand, Italy reminded the Allies of their wartime promises re Austo-Hungarian territory and, on the other han, sponsored paramilitary groups with the aim of breaking up the new Yugoslav state. Italy was also sponsoring Albanian separatist paramilitary groups. Italian interference engendered the creation in those regions bordering Italy of a pro-Yugoslav, anti-Italian groups, ORJUNA which also attacked communist, members of the Croatian peasants’ party and retired Hapsburg army officers. ORJUNA was succeeded by TIGR which continued resistance to Italy in those regions which were contested by both countries.

It is also worth recording the attacks on religious minorities in the region, notably the Moslem population, throughout and after this period continuing into the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.

The chapter on paramilitarism in the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire makes for even more heartrending reading.

The Collapsing Ottoman Empire

“In the process of Hapsburg, Ottoman and Russian imperial collapse, between 1912 and 1923, millions of soldiers were killed in regular warfare. But hundreds of thousands of unarmed civilians also died – victims of expulsions, pogroms and other forms of persecution and mass violence. The Balkan wars of 1912-13 virtually erased the Ottoman Empire from the Balkans and marked a devastating blow to Ottoman political culture. The years of 1915-16 saw the destruction of the bulk of the Anatolian Armenians, primarily (but not exclusively) by Young Turk paramilitary units. Lastly, the period of 1917-23 is of great significance for the history of the Caucuses, both North and South, as it witnessed wars of annihilation and the massacre of civilians. All three episodes occurred amidst a deep crisis of inter-state relations and societal conditions, as well as inter-ethnic relationships between and within states. In all three episodes, paramilitary units played a decisive role in the initiation and execution of violence against both armed combatants and unarmed civilians.”

The Ottoman paramilitary units were mostly made of unemployed young men who were refugees from the Balkans. They numbered about 30,000. It is an example, says the author, of the phenomenon whereby victims of violence in one society cross borders and become the recruits for paramilitary units that inflicts violence on another ethnic group. In the troubled world of the late 19th and early 20th century Balkans, the Ottomans used paramilitaries to kill civilians randomly as a method of securing the submission of recalcitrant populations.

A watershed in the nature and extent of paramilitary violence in the Ottoman Empire came with the Young Turk coup d’état of 23 January 1913. Their party, the CUP, then imposed a de facto political dictatorship. Assassinations within the political classes became commonplace.

After January 1913, two of the leading lights in the CUP began merging the disunited and disparate groups of paramilitaries into the “Special Organisation”. In fact, there were five groups of Ottoman paramilitary forces during WWI. First, there was the rural gendarmerie in both static and mobile units. They were trained to modern standards and lead by a professional officer corps. The gendarmerie was used to keep order in the countryside. Second was the tribal cavalry that had grown out of 29 Kurdish and Circassian cavalry regiments. These were led by tribal chieftains and were responsible for various internal security units. The third group were the “volunteers” made of various Islamic groups from outside the Ottoman Empire, mostly Turkish refugees from the Balkans. Fourth was the Special Organisation which was initially an intelligence service that sought to foment insurrection in enemy territory and carry out espionage, counterespionage, and counterinsurgency. The command structure of this organisation would absorb the other groups. Finally, a fifth group were simply called “bands”, a hodgepodge of non-military guerrilla groups not fully subject to centralized command and control but often acting as the paramilitary wing of individual Young Turk leaders. They enjoyed some political protection for their crimes because of their association with the various Young Turk leaders. They were poor unemployed men, referred to in Turkish as “roughnecks” or “vagrants”.

The CUP created paramilitary units by releasing criminals from prison, preferably those with associations with outlaw gangs.

Paramilitary units were used in the Caucasus, primarily against the Russians. In the early winter of 1914, these groups infiltrated into Russian territory and Persia to incite the Muslim populations to rise in rebellion and join the Ottoman forces. In fact, the paramilitary units engaged in plundering and massacres of the local non-Muslim populations. This also applied on Ottoman territory when the Ottoman army was forced back. The Ottoman regular army found the existence and behaviour of these groups both objectionable and problematic, but the paramilitaries had political cover from the CUP.

This lead on to the Armenian genocide of the winter of 1914-1915 in which the paramilitary groups were to the fore.

Ethnic Greek populations were also a target. Some 100,000 ethnic Greeks were expelled to Greece in 1914 alone, and the remaining population was exposed to ethnic terror, ordered by the Young Turks. In the Turko-Greek war of 1919 to 1923, the same Young Turk paramilitary units massacred Greeks in Smyrna, and murdered and expelled the Pontic Greeks from the Black Sea coast.

In the South Caucasus, the collapse of the Russian state during 1917 removed a constraint on the Armenian-Azeri conflict, the Ottoman Empire having collapsed as well after 1918. The most notorious examples were the massacre of Azeris in Baku on Black Sunday, 31st March 1918 and the massacre of thousands of Armenians in the capital of Nagorno-Karabagh, Shusha on 22-26th March 1920, in revenge for a failed Armenian paramilitary raid.

Armenian nationalist parties sought to inflict vengeance for the genocide of 1914-15. This happened in three phases – in 1916-18 in occupied Ottoman territory (ie occupied by the Russians), in 1917-22 in the South Caucasus, and international assassinations against the former Young Turk leaders in the 1920s.

When the Russians took Ottoman territory, they used Armenian paramilitaries and Cossack cavalry against the local Muslim population. In the valley of the Chorukh river in the South West Caucasus 45,000 civilians were killed, mostly by Cossack units. The Kurds were as much a target for the Armenian paramilitaries as were the Muslims. The Turkish and Kurdish military units with the Ottomans would take no Armenian prisoners, and vice versa. It was an ethnic war of annihilation. The Russian writer Shklovskii said that he had seen Galicia and Poland during the war “but that was all paradise compared to Kurdistan”.

By the summer of 1918, inter-ethnic warfare between Azeri and Armenian paramilitaries had enveloped several pockets in the South Caucasus. The various Armenian militias were the power in a number of areas and held the monopoly of violence.

The Armenian Dashnak party decided in 1919 to orchestrate an assassination campaign against the now former Young Turk leaders, wherever they were. For example, Cemal Pasha was killed on 21 July 1922 in Tbilisi, in Georgia by Stepan Dzaghigian. Dashnak agents also killed many Armenians whom they accused of collaborating with the Young Turks and denouncing other Armenians during the genocide.

In conclusion, the success of the Balkan ethnic groups in expelling the Ottomans by the use of paramilitary power encouraged other groups throughout the Empire to do likewise, including expelling or annihilating rival ethnic groups. These chain reactions could not be stopped by neighbouring countries or the Great Powers. The Armenian genocide happened under the noses of the German army, and the massacre of Azeris in Baku in the presence of the British army.

Paramilitary groups were also used to quell dissident groups within Turkey, eg against the Sunni Kurds in Diyarbekir in 1925 and the Shi’ite Kurds in Dersim in 1937. More recently, Turkish action against the Kurdish PKK has involved extra-legal paramilitaries conducting a scorched earth campaign in 1994-95. The First World War is not over yet.

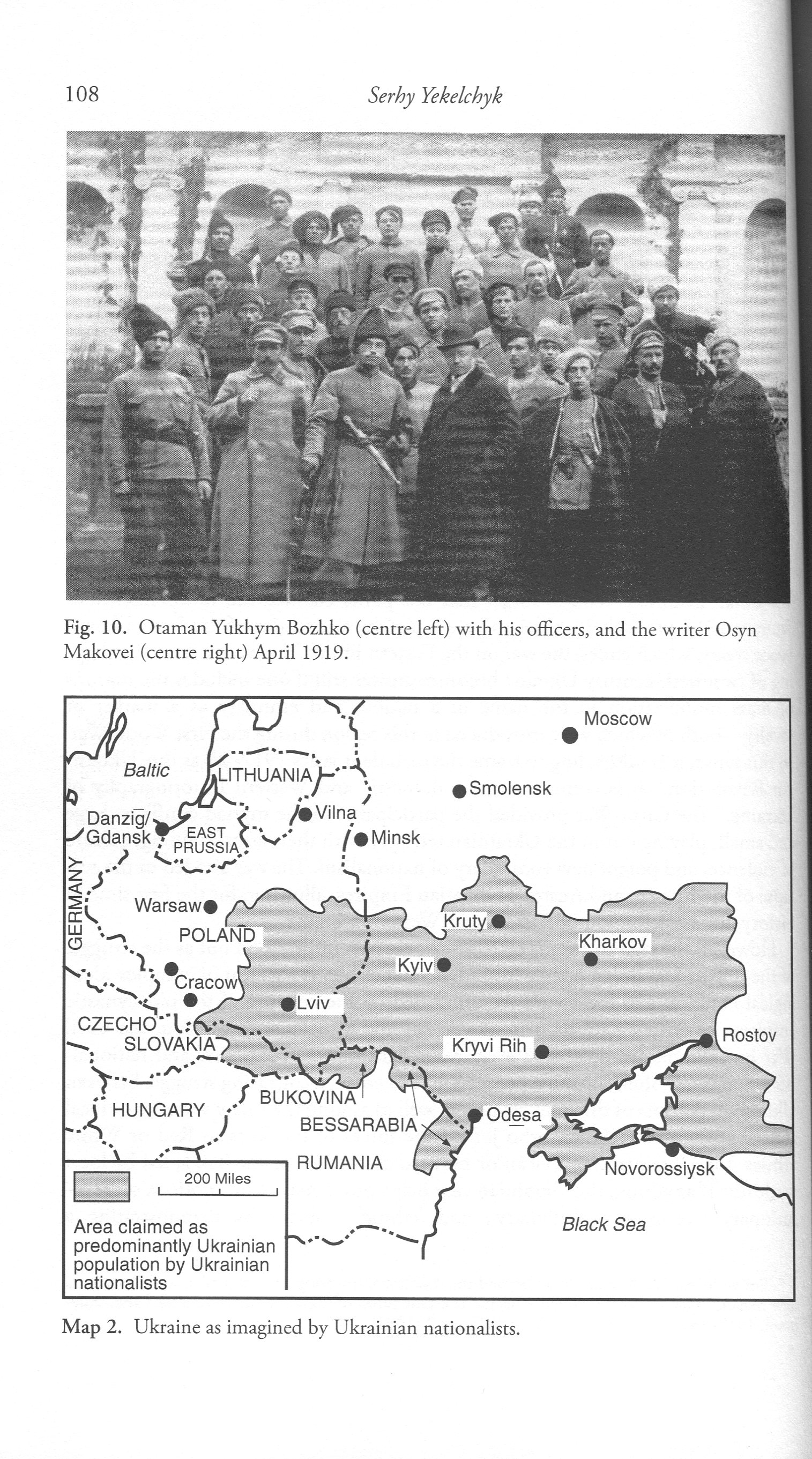

Ukrainian paramilitaries 1919

Ukrainian paramilitaries 1919

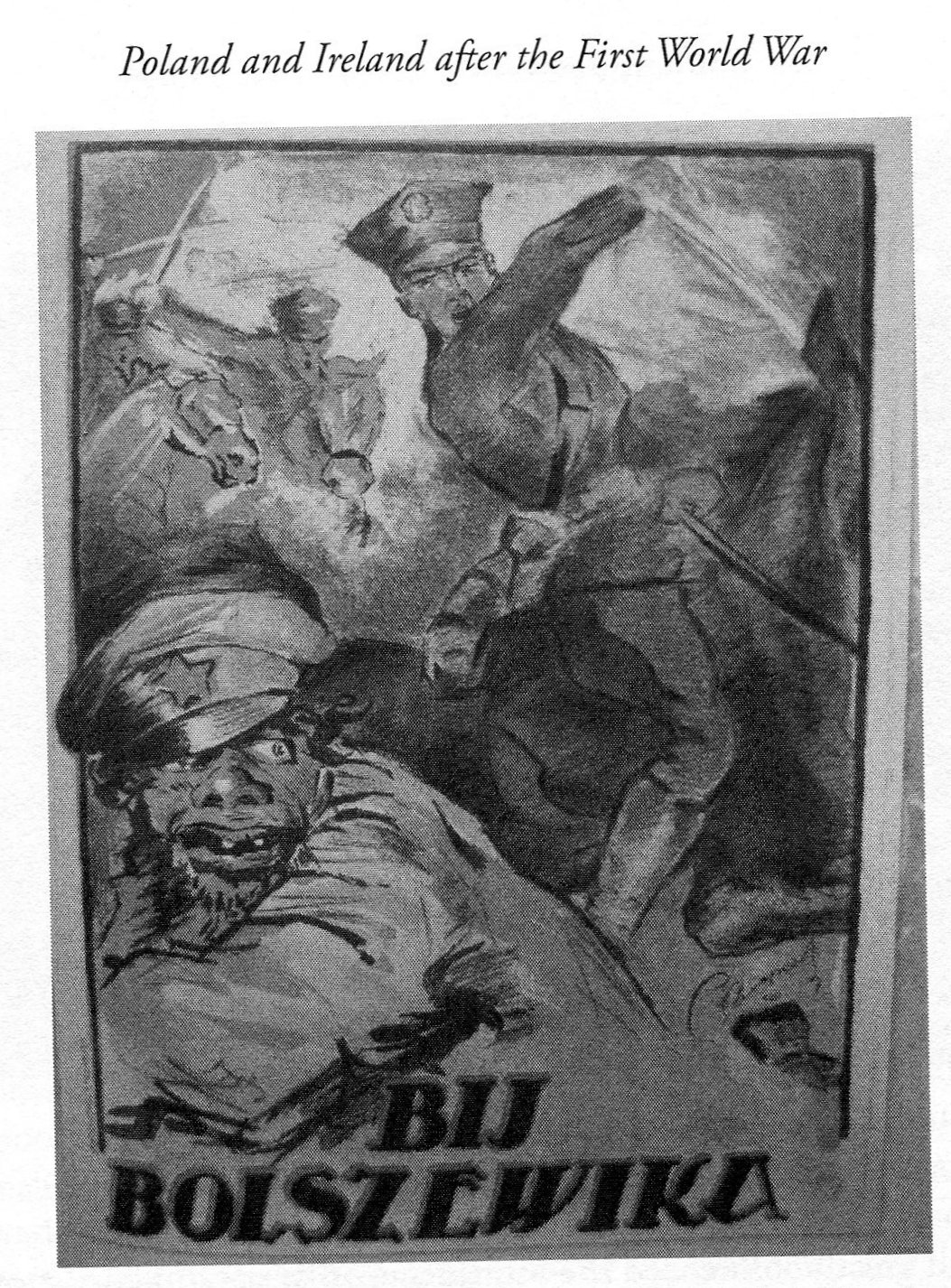

Poster from the Soviet-Polish war of 1920 - Beat the Bolsheviks!

Poster from the Soviet-Polish war of 1920 - Beat the Bolsheviks!