The Dragon’s Voice

Welcome to the November/December issue.

In this issue, we have an article on the Canadian War Memorials Fund, which employed artists to record Canada’s involvement in WWI on the home front and overseas.

We have two book reviews. One is on paramilitary violence before, during and after WWI. The second review deals with a book looking at the military and political background leading up to WWI and asking the question – was it an improbable war?

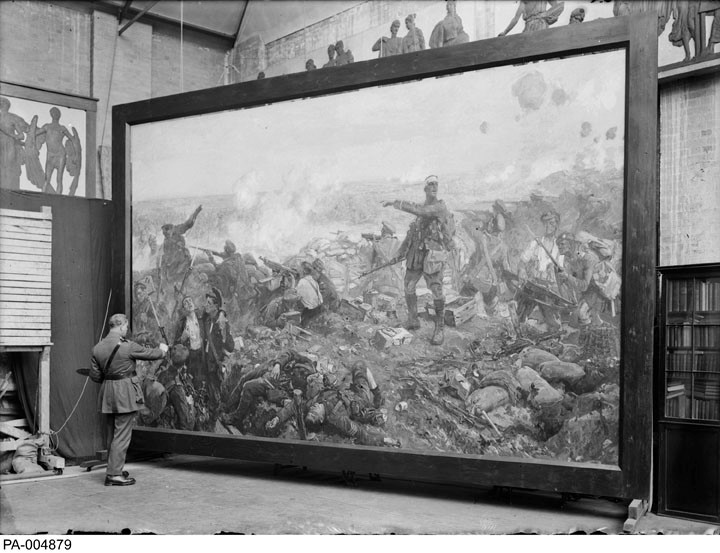

The Canadian War Memorials Fund

Caroline Adams

Canada was one of the first countries to establish a war art programme. The Canadian War Memorials Fund was established in 1916 by Lord Beaverbrook and continued till 1919. It was run by the Canadian Army War Records Office.

Over the three years, it employed over 100 artists, British, Australian, Yugoslavian and Belgian as well as Canadian. They produced about 1000 works of art, both pictures and sculptures, depicting battlefield scenes and industrial and agricultural work on the home front.

None of the works were exhibited during the war, but afterwards they were seen in exhibitions in London, New York, Ottawa, Montreal and Toronto. These big international exhibitions gave the artists the experience of having their work evaluated by leading critics and gallery officials. The Canadian War Memorials Fund therefore not only gave Canada an artistic memorial of their participation in WW1, but also gave Canadian art and artists’ recognition, both at home and internationally.

The Second Battle of Ypres. Richard Jack

Library and Archives Canada PA-004879

Houses of Ypres A Y Jackson

Canadian War Museum, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art 19710261-0179

For What? Frederick Varley

Canadian War Museum/Beaverbrook Collection of War Art/19710261-0770)

Reference:

The Canadian Encyclopaedia

Book Review

War in Peace

Robert Gerwarth and John Horne

Oxford University Press 2010

This book stems from an academic symposium on paramilitary violence in the period from before WWI to the 1917 Russian revolution and into the 1920s. Each chapter is written by a different author, some from the countries concerned. Robert Gerwarth is professor of Modern History at University College Dublin and John Horne is now the emeritus professor of Modern European History at Trinity College Dublin. The location of their alma mater means a wider viewpoint than is often the case with historians based elsewhere. For the record, Robert is German and John is English.

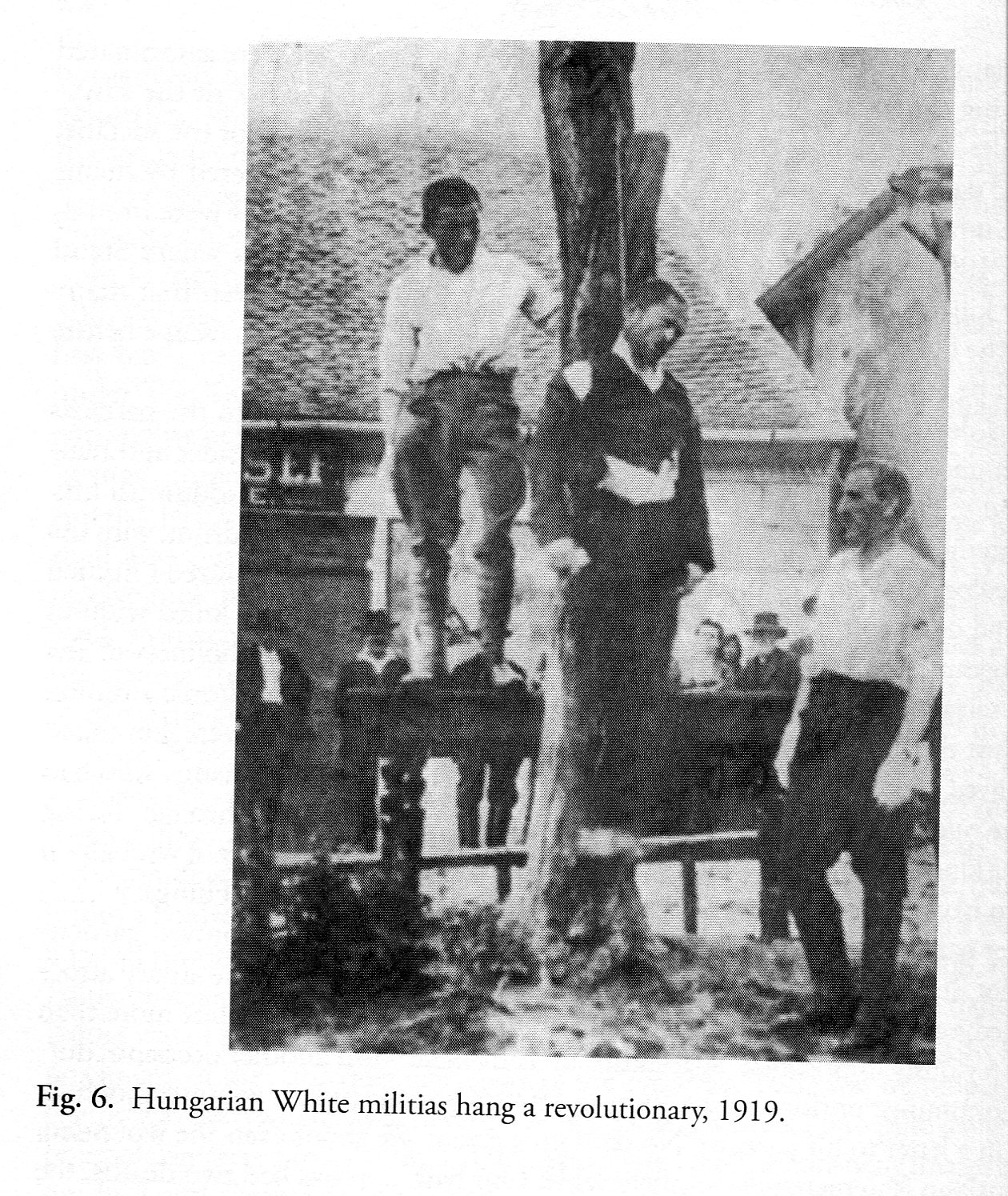

Paramilitary violence was an important aspect of the clashes unleashed by class revolution Russia in 1917. It lead to the counter revolutions in central and Eastern Europe, including Finland and Italy, which in the name of order and authority reacted against a mythic version of the Bolshevik class violence – a case of getting your retaliation in first, if you will. It also helped to shape the struggles over borders and ethnicity in the new states that replaces the multi-ethnic empires of Russia, Austro-Hungary and the Ottomans. It was prominent on all sides in the Irish War of Independence. Paramilitary violence was charged with political significance and acquired a long-lasting symbolism and influence. Various of the movements in World War Two can trace their origins to this period. One thinks of, for example, the Nazis in Germany, the Fascists in Italy, the Ustase, IMRO and Cetniks in Yugoslavia, the communist groups in many countries, and other quasi-fascist groups in, eg, Latvia. Being a civilian minding your own business was a very hazardous, and often fatal, existence in any country where any of these groups operated. As with any civil war situation, the picture is often a complex one of competing groups with an ideology of sort, local warlords and criminals. Two interesting examples where paramilitary violence did not occur on any major scale were mainland Britain and France.

Perhaps two of the most interesting chapters for those interested in WWI are those by John Paul Newman on the Balkans in the 1912-1923 period, and Ugur Umit Ungor on paramilitary violence in the collapsing Ottoman Empire.

Lest you think that the whole issue is something the “nasty foreigners” did, the British government of the day, and Churchill in particular, did the same thing in Ireland by unleashing the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries. (There are chapters in the book on this aspect). The CIGS of the day, Henry Wilson, said that using paramilitaries would be a disaster, and that eventually the army would have to sort out the mess. So, July of this year, 2021, marked the centenary of the truce in the War of Independence, at the behest of King George V, and 2022 is the centenary of the loss of the 26 counties of what is today the Irish republic. Paramilitaries caste a long shadow.

The Balkans – where WWI started

Newman’s chapter on the Balkans starts with the history of the region in the 19th century and the struggles by various groups against the Ottomans, as of course this area was part of the Ottoman Empire. These groups emerged with an increasing awareness of national identity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Large paramilitary bands with coherent political goals and official support originated from the early 20th century. They were in conflict with the Ottomans and with each other, more so after the Ottomans were expelled. Both Serbia and Bulgaria used existing paramilitary groups in the first Balkan War. The period between the end of the Second Balkan War and the start of WWI, 1912-1914, was marked by attacks on civilian populations, and each other, by armed bands representing a national cause. This was easier, if that is the right word, because the overarching authority of the Ottomans had been removed. The Kingdom of Serbia was the clear winner in the Balkan Wars. It saw as further targets for its nationalist dream the Hapsburg states of Bosnia and Herzogovina and, in the north, the lands of the Vojvodina (which indeed is part of modern Serbia today). However, Serbia was in no fit condition after two Balkan wars to engage in a struggle with anybody, much less the Hapsburg state. Nevertheless, Serbian nationalist elements both inside and outside the state sought to engage the oppressive colonist of Serbian populated lands, the Hapsburgs. Thus, the two years leading up to WWI were marked by a number of failed assassination attempts on Hapsburg officials and dignitaries carried out by members of the South Slav youth. The assassination of Franz Ferdinand and his wife by a Serb schoolboy was very nearly yet another incompetent assassination attempt on Austro-Hungarian officialdom.

Thus, WWI for the nationalist groups in the Balkans became synonymous with the struggle to rid themselves of the Austro-Hungarians and their central power allies, the Bulgarians. (There was a significant ethnic Bulgarian population in the Balkans at the time, outside the borders of modern Bulgaria).

Yugoslavia (“the land of the southern Slavs”) was created after WWI as an amalgam of the various ethnic groups and religions within the Balkans. The southern portion would be contested after WWI as it had been before WWI by the paramilitary groups (that is Macedonia, Kosovo and Northern Albania. Bulgaria experienced major upheaval. It had been on the side of the Central Powers and lost territory as a result of the Treaty of Neuilly. Thus, from the spring of 1920 the paramilitaries of IMRO crossed the border from Bulgaria to carry out attacks on Yugoslav civilians and gendarmes, in territory which Bulgarians regarded as theirs. The Bulgarian Prime Minister Stamboliski who had sought to relinquish claims on Macedonia territory and make the country part of the European status quo was kidnapped, tortured and murdered by IMRO in 1923.

Serbia, now part of Yugoslavia, used its army and paramilitaries to tackle IMRO incursions into Yugoslavia and fight Albanian guerrilla bands, Kacaks, in Kosovo and Northern Albania and “punish” anyone they did not happen to like. Macedonia was declared to be part of Serbia. A process of colonisation commenced with Serbs being encouraged to move to the area, and the suppression of all Bulgarian institutions.

In that part of the new Yugoslavia comprising the Adriatic coast, the Italian- Yugoslav border and the central European lands of Croatia and Slovenia, matters were complicated by Italy intermeddling and arming paramilitary groups. Italy had been promised by the Allies during WWI that it would get Dalmatia in the break-up of Austro-Hungary, but the Allies went back on their promise when they created Yugoslavia. So, Italy has a grudge with the new Yugoslav state. Typical of the disintegration of Austro-Hungary were the “green cadres” that were active in Croatia and Slovenia. These were Hapsburg deserters, draft dodgers and returned PoWs.

The Croat legion was a group of ex Hapsburg army officers who sought to reverse the territorial changes of the Paris treaties and take Croatia out of the Yugoslav state. Their most important sponsor was Italy which pursued a double move. On one hand, Italy reminded the Allies of their wartime promises re Austo-Hungarian territory and, on the other hand, sponsored paramilitary groups with the aim of breaking up the new Yugoslav state. Italy was also sponsoring Albanian separatist paramilitary groups. Italian interference engendered the creation in those regions bordering Italy of a pro-Yugoslav, anti-Italian groups, ORJUNA which also attacked communist, members of the Croatian peasants’ party and retired Hapsburg army officers. ORJUNA was succeeded by TIGR which continued resistance to Italy in those regions which were contested by both countries.

It is also worth recording the attacks on religious minorities in the region, notably the Moslem population, throughout and after this period continuing into the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.

The chapter on paramilitarism in the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire makes for even more heartrending reading.

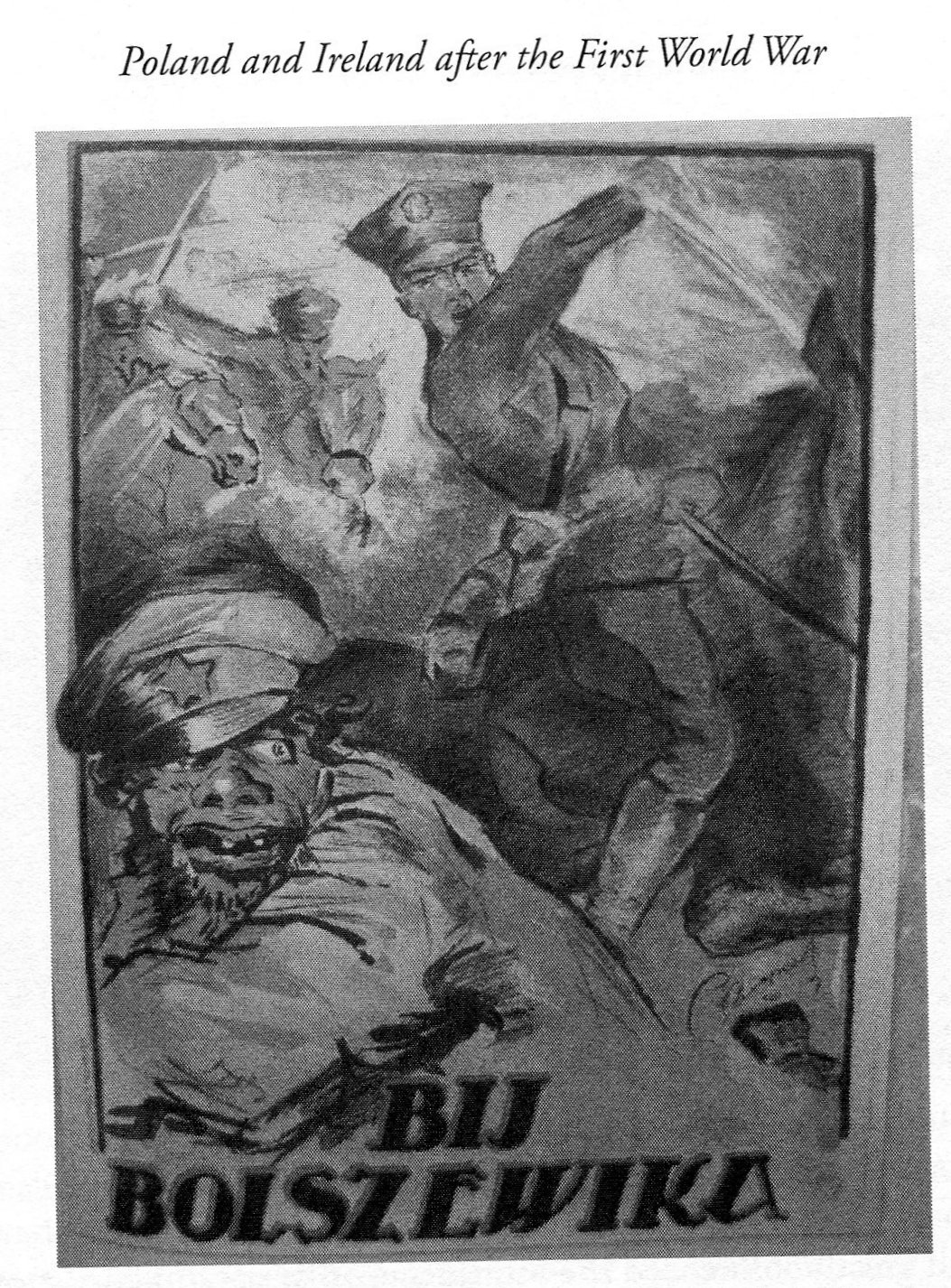

A Polish Poster from the Soviet-Polish War of 1920 – “Beat the Bolshevik”

The Collapsing Ottoman Empire

“In the process of Hapsburg, Ottoman and Russian imperial collapse, between 1912 and 1923, millions of soldiers were killed in regular warfare. But hundreds of thousands of unarmed civilians also died – victims of expulsions, pogroms and other forms of persecution and mass violence. The Balkan wars of 1912-13 virtually erased the Ottoman Empire from the Balkans and marked a devastating blow to Ottoman political culture. The years of 1915-16 saw the destruction of the bulk of the Anatolian Armenians, primarily (but not exclusively) by Young Turk paramilitary units. Lastly, the period of 1917-23 is of great significance for the history of the Caucuses, both North and South, as it witnessed wars of annihilation and the massacre of civilians. All three episodes occurred amidst a deep crisis of inter-state relations and societal conditions, as well as inter-ethnic relationships between and within states. In all three episodes, paramilitary units played a decisive role in the initiation and execution of violence against both armed combatants and unarmed civilians.”

The Ottoman paramilitary units were mostly made of unemployed young men who were refugees from the Balkans. They numbered about 30,000. It is an example, says the author, of the phenomenon whereby victims of violence in one society cross borders and become the recruits for paramilitary units that inflicts violence on another ethnic group. In the troubled world of the late 19th and early 20th century Balkans, the Ottomans used paramilitaries to kill civilians randomly as a method of securing the submission of recalcitrant populations.

A watershed in the nature and extent of paramilitary violence in the Ottoman Empire came with the Young Turk coup d’état of 23 January 1913. Their party, the CUP, then imposed a de facto political dictatorship. Assassinations within the political classes became commonplace.

After January 1913, two of the leading lights in the CUP began merging the disunited and disparate groups of paramilitaries into the “Special Organisation”. In fact, there were five groups of Ottoman paramilitary forces during WWI. First, there was the rural gendarmerie in both static and mobile units. They were trained to modern standards and lead by a professional officer corps. The gendarmerie was used to keep order in the countryside. Second was the tribal cavalry that had grown out of 29 Kurdish and Circassian cavalry regiments. These were led by tribal chieftains and were responsible for various internal security units. The third group were the “volunteers” made of various Islamic groups from outside the Ottoman Empire, mostly Turkish refugees from the Balkans. Fourth was the Special Organisation which was initially an intelligence service that sought to foment insurrection in enemy territory and carry out espionage, counterespionage, and counterinsurgency. The command structure of this organisation would absorb the other groups. Finally, a fifth group were simply called “bands”, a hodgepodge of non-military guerrilla groups not fully subject to centralized command and control but often acting as the paramilitary wing of individual Young Turk leaders. They enjoyed some political protection for their crimes because of their association with the various Young Turk leaders. They were poor unemployed men, referred to in Turkish as “roughnecks” or “vagrants”.

The CUP created paramilitary units by releasing criminals from prison, preferably those with associations with outlaw gangs.

Paramilitary units were used in the Caucasus, primarily against the Russians. In the early winter of 1914, these groups infiltrated into Russian territory and Persia to incite the Muslim populations to rise in rebellion and join the Ottoman forces. In fact, the paramilitary units engaged in plundering and massacres of the local non-Muslim populations. This also applied on Ottoman territory when the Ottoman army was forced back. The Ottoman regular army found the existence and behaviour of these groups both objectionable and problematic, but the paramilitaries had political cover from the CUP.

This lead on to the Armenian genocide of the winter of 1914-1915 in which the paramilitary groups were to the fore.

Ethnic Greek populations were also a target. Some 100,000 ethnic Greeks were expelled to Greece in 1914 alone, and the remaining population was exposed to ethnic terror, ordered by the Young Turks. In the Turko-Greek war of 1919 to 1923, the same Young Turk paramilitary units massacred Greeks in Smyrna, and murdered and expelled the Pontic Greeks from the Black Sea coast.

In the South Caucasus, the collapse of the Russian state during 1917 removed a constraint on the Armenian-Azeri conflict, the Ottoman Empire having collapsed as well after 1918. The most notorious examples were the massacre of Azeris in Baku on Black Sunday, 31st March 1918 and the massacre of thousands of Armenians in the capital of Nagorno-Karabagh, Shusha on 22-26th March 1920, in revenge for a failed Armenian paramilitary raid.

Armenian nationalist parties sought to inflict vengeance for the genocide of 1914-15. This happened in three phases – in 1916-18 in occupied Ottoman territory (ie occupied by the Russians), in 1917-22 in the South Caucasus, and international assassinations against the former Young Turk leaders in the 1920s.

When the Russians took Ottoman territory, they used Armenian paramilitaries and Cossack cavalry against the local Muslim population. In the valley of the Chorukh river in the South West Caucasus 45,000 civilians were killed, mostly by Cossack units. The Kurds were as much a target for the Armenian paramilitaries as were the Muslims. The Turkish and Kurdish military units with the Ottomans would take no Armenian prisoners, and vice versa. It was an ethnic war of annihilation. The Russian writer Shklovskii said that he had seen Galicia and Poland during the war “but that was all paradise compared to Kurdistan”.

By the summer of 1918, inter-ethnic warfare between Azeri and Armenian paramilitaries had enveloped several pockets in the South Caucasus. The various Armenian militias were the power in a number of areas and held the monopoly of violence.

The Armenian Dashnak party decided in 1919 to orchestrate an assassination campaign against the now former Young Turk leaders, wherever they were. For example, Cemal Pasha was killed on 21 July 1922 in Tbilisi, in Georgia by Stepan Dzaghigian. Dashnak agents also killed many Armenians whom they accused of collaborating with the Young Turks and denouncing other Armenians during the genocide.

In conclusion, the success of the Balkan ethnic groups in expelling the Ottomans by the use of paramilitary power encouraged other groups throughout the Empire to do likewise, including expelling or annihilating rival ethnic groups. These chain reactions could not be stopped by neighbouring countries or the Great Powers. The Armenian genocide happened under the noses of the German army, and the massacre of Azeris in Baku in the presence of the British army.

Paramilitary groups were also used to quell dissident groups within Turkey, eg against the Sunni Kurds in Diyarbekir in 1925 and the Shi’ite Kurds in Dersim in 1937. More recently, Turkish action against the Kurdish PKK has involved extra-legal paramilitaries conducting a scorched earth campaign in 1994-95. The First World War is not over yet.

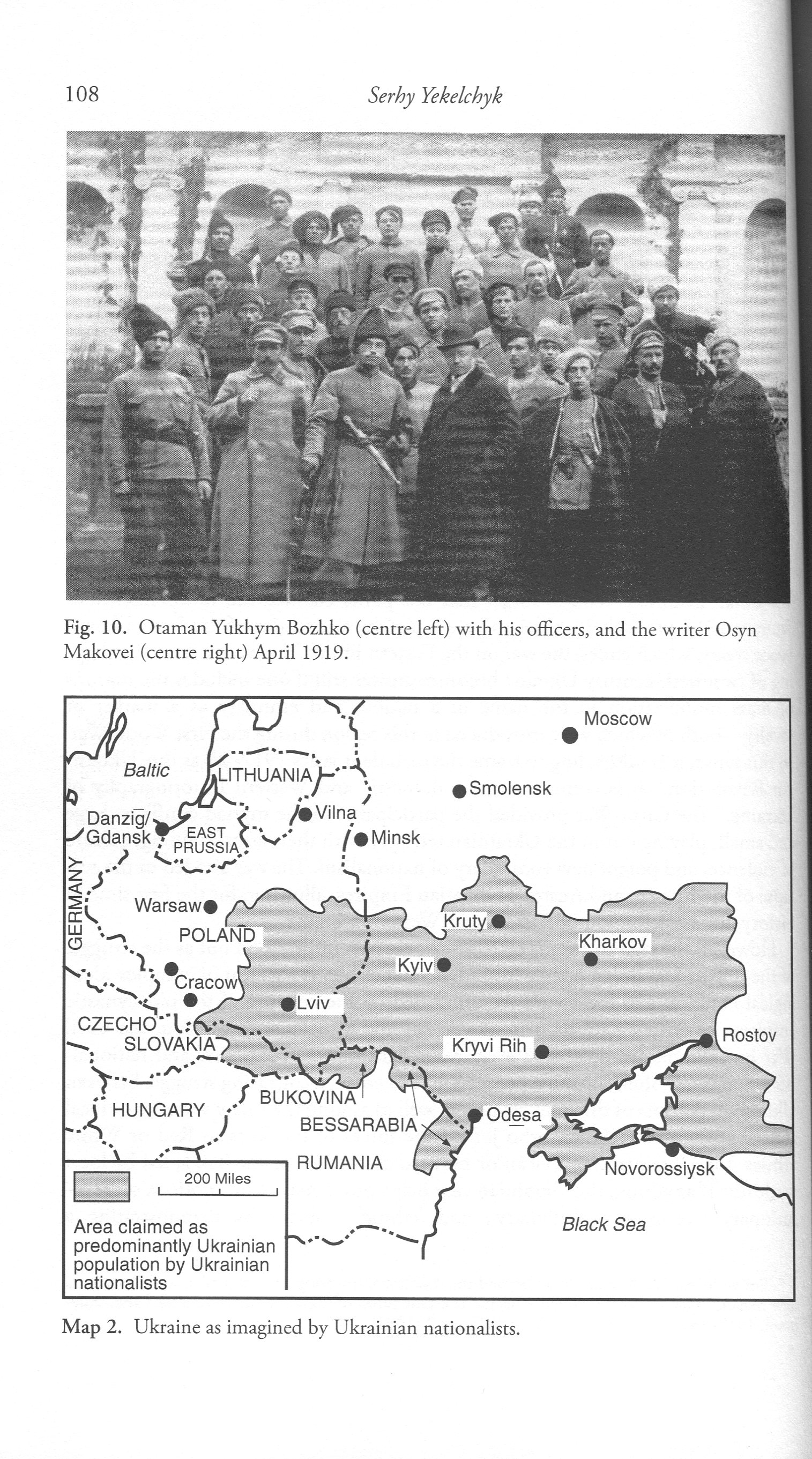

Ukrainian paramilitaries, 1919

Book Review

An Improbable War:

The outbreak of World War I and European Political culture before 1914

Edited by Holger Afflerbach and David Stevenson

Berghahn Books 2007

This is a collection of essays by eminent historians and stems from a symposium held at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia in 2004. The basic premise of the articles is that WWI should not have happened – so what went wrong? Holger Afflerbach is Professor of Modern European History at Leeds University, and David Stevenson is the Professor of International History at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

It is worth noting at the start that the consensus seems to be that the best account of the political crisis in July and August 1914 that lead to outbreak of WWI is the book, in three volumes, by Luigi Albertini, a conclusion which I would agree with. The current work is not concerned with the July crisis, as such. Rather, it looks at the historical, political and cultural factors at play in the relevant countries which lead to the crisis and to WWI.

The book starts with an introduction from former US President Jimmy Carter. You may wonder what his connection with WWI is. In fact, his father served in Meuse-Argonne in WWI. Jimmy Carter was in the US Navy and was the first member of his family even to finish high school. He served in WWII and Korea.

His introduction refers to the excessively–binding treaty system of the day being a factor in the genesis of WWI. He refers to the fact that there were no wars in Europe for forty-three years before WWI. In the US, WWI is much less in the consciousness today than are more recent conflicts, yet the US lost more soldiers in WWI than in Korea and Vietnam combined. Four empires disappeared as a result of WWI, and it was in some ways the beginning of the end for others.

Apparently, President Kennedy told his advisers to read “The Guns of August” by Barbara Tuchman, so that they would be better informed about the history of WWI and be able to avoid the same mistakes. This book is often criticised by modern historians but it easily still outsells many more recent works.

President Carter sees the League of Nations as a positive development of WWI, and eventually we had the United Nations, after WWII, as an attempt to avoid wars.

On political leaders, Carter contends that certain leaders of the WWI era saw war as a way to exert their political influence and perhaps territorial expansion. They thought they could go to war with impunity and win without the danger of loss.

His hope for the book is that one can learn some lessons on how to avoid a future catastrophe.

In the book itself, the question is whether WWI was a logical response to the political conditions in Europe in 1914, or rather a reaction against, and a break with, them. So, the issue is the degree of probability and inevitability in the outbreak of the conflict.

One aspect is whether WWI was caused by a series of serious professional mistakes by a comparatively small group of diplomats, politicians and military leaders, or is it an automatic outcome of the mind-set of the European generation of 1914? It was a common suggestion of many writers in the 1990s that European societies and their governments, in the summer of 1914, were filled with suicidal enthusiasm for the incipient conflict. However, much new research in recent years has successfully challenged that view. The current view suggests that public opinion in the belligerent countries was highly differentiated by region and by social class.

The book seeks to provoke a corresponding reappraisal of how the European political culture before 1914 dealt with the question of war and peace. First, the book seeks to cover not only the culture of individual states but also pan-European themes such as the rules of diplomacy, honour, gender, religion, and the arts.

So, in the first chapter Paul Schroeder contends that WWI was ultimately the outcome of changes in the unwritten rules, or norms, of the international system. The ever increasing brutality of these rules placed enormous pressure on some members of the international community, robbed them of breathing space, and ultimately forced them into suicidal action. According to Schroeder, Austro-Hungary may have become a perpetrator, but it was also a victim. In effect, he suggests that war was essentially unavoidable by 1914.

Next, Matthias Schultz looks at European congressional diplomacy between 1815 and 1914. He contends that even at the end of this period, adequate peacekeeping mechanisms existed, and that the Austro Serbian crisis could have been resolved by a conference or by a multilateral peacekeeping effort, instead of a forceful and unilateral Austrian action with German support. As the international system lost ethical foundation, war became more probable. Schultz characterises the Hapsburg monarchy, from a statistical analysis of the incidence of crises, as the leading fomenter of instability in Europe. He therefore disagrees with Schroeder who sees Austro Hungary as a great victim of the international system.

Samuel Williamson also looks at the situation in Vienna. He analyses the decision making process of Austro Hungary during 1914. His chapter shows that the Hapsburg political elite had not resolved the question of war against Serbia even before the Sarajevo assassinations, and that they had other political priorities. Thus, the Sarajevo assassinations became the decisive moment, in that without the murder of France Ferdinand and his wife, there would have been no decision by the Austrian government for war with Serbia. The author contends that German pressure was not decisive, and that the Hapsburg leaders made their own decisions.

John Rohl provides a powerful analysis of Wilhelm II and his political line, personal goals and responsibility during the July crisis. He believes that the German leaders deliberately started the war and traces the roots of the conflict to the German political system and the personality of the German ruler, whom he indicts for his duplicity and recklessness.

Jost Dulffer discusses the two Hague peace conferences and their attempts to limit the level of armaments and to outlaw the use of certain weapons. Alternatives to the existing European balance of power system, with its adjustment mechanisms of arms build ups and deterrence, had no chance of making headway in an era when every state was keen on keeping control over its own sovereignty, including the right to configure its armed forces in the light of its own strategic planning and perceived security needs. There was a third peace conference envisaged for 1915. Had not war intervened, the momentum in favour of arms control and international arbitration might have developed further.

Michael Epkenhans analyses the Anglo German naval race, showing how Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, Secretary of State of the Imperial German Naval Office, overcame all internal resistance to his fleet building programme. Unquestionably, the naval rivalry poisoned Anglo German relations. However, by 1914 the most acute phase of the naval race was over and the British had won it, not least because Tirpitz and the German Navy had run out of money. Although the naval rivalry contributed to the deterioration of the international situation, and especially to Germany’s place within it, it did not in itself trigger the outbreak of the war.

Similarly, in his discussion of the land armaments race David Stevenson confronts directly the question of whether or not the world war was improbable. He argues that land armaments competition indeed destabilised European international relations, but that the leaders of the powers could have found peaceful solutions to their security predicaments. Earlier arms races had ended without hostilities and the pre-1914 race, although a critical danger to European peace, might have evolved into a non-violent confrontation or “cold war”.

The essay by Gunther Kronenbitter investigates the war planning of Helmut von Moltke the younger and Franz Conrad von Hotzendorf, the German and Austrian general staff chiefs. Both men agreed that the impact of a large scale continental war would have devastating repercussions on European civilisation for decades. They also recognised the unpredictability of the outcome of such a conflict. Yet precisely because they were trapped by their understanding of national and personal duty, they prepared for a war which they thought would inevitably be a disaster for Europe and for their countries. Whilst neither chief had the authority to initiate a war, their narrow understanding of military security subjected European peace to an enormous structural burden. In other words, although developments in armaments policy and in strategic planning did serve to endanger peace, they did not so destabilise the international order as to make war unavoidable.

Holger Afflerbach addresses the central themes of the volume by analysing the expectations about war current among the European governments of 1914. His basic contention is that, if contemporaries had really believed war to be unavoidable, then everyone would have expected that after Sarajevo events would lead quickly to the outbreak of hostilities. But in fact the opposite was true. The elites of the era did not believe that a Great War was probable and they were completely surprised by its outbreak. The notion that nobody would risk such a devastating catastrophe was all the more widely accepted because of the highly developed system of deterrence of the day. Afflerbach therefore denies that European societies of the day expected a cataclysm, contrary to the thoughts of earlier historians. He also discusses the various military leaders who dreamed of a great European war out of self-indulgent motives, but he suggests that even they believed that such a war was both improbable and liable to be immensely destructive. However, the danger in this situation was that some statesmen were so confident that a Great War was impossible that they planned their actions without the necessary caution. The war was therefore improbable because it went against the tides of that time. The actual outbreak of war was even a consequence of the misplaced confidence that peace was secure.

Friedrich Kiessling pursues a similar line of argument in his analysis of policymakers conduct during the diplomatic crises of the years leading up to 1914. He insists that in trying to explain the war’s origins it is a mistake to focus only on those factors which seemingly lead to an escalation of international tensions. He looks instead at efforts to achieve detente and de- escalation in political conflict. Paradoxically, this policy of seeking détente may have been too successful, leading to miscalculations by some of Europe's leading statesmen in the July crisis. Because compromise had been achieved in previous crises and war had repeatedly been averted, the assumption may have been that in 1914, too, conflict could be avoided. The mind-set of “improbable war”, or of dangerous faith in détente, made key decision makers perilously insouciant. For both Afflerbach and Kiesssling, the outbreak of war in Europe was a consequence of carelessness caused by overconfidence, comparable to the complacency of the crew of the Titanic who failed to reduce their speed at the moment of danger.

Roger Chickering analyses the popular mood in the summer of 1914, focusing his attention on the middle-sized German city of Freiburg. It is a combined general survey of the public opinion literature, with an interesting case study. He adds:

"the dramatic scenes of the summer of 1914 ought to be understood in the light of their own political and cultural dynamics. They should not be taken as evidence that an inveterate German war enthusiasm made war probable or inevitable.”

Consequently, his contribution weakens the hypothesis that WWI was unavoidable.

The next chapter, by Joshua Sanborn, deals with developments in Russia, again with reference to the question of whether the political culture in this country made the Great War probable or not. His complex arguments show how difficult it is to find clear and simple trends in pre-war societies. He discusses the evidence for growing popular patriotism and militarism in pre-1914 Russia, as in other European countries. Examples include the celebration of the Franco-Russian alliance, government-led centenary commemorations of the victory of 1812, the abolition of schoolteachers’ exemption from conscription, changes to the school curriculum, and the creation of new patriotic societies. On the other hand, he also demonstrates the reservations felt about these developments on the part of pacifists and of authoritarian conservatives, including the Tsar. Yet, he concludes that a particular form of patriotism, that is a deep concern for Russia's status as a great power, was decisive in hardening policy in the July crisis and impelled decision-makers to opt for a war that no-one regarded with enthusiasm and was widely considered to be highly inopportune.

There are chapters on the roles of culture, religion and gender in international relations before 1914, as well as to the topic of internationalism as an influence on the question of European peace. In particular, Ute Frevert in her essay states that gender-related understanding of honour in European societies had a distinctive influence on the events of summer 1914. In short, she refers to manly posturing which made attempts to peacefully solve the crisis extremely difficult.

The last three chapters describe the view from afar. Ottoman Turkish politics and their view on Europe are analysed in a chapter by Mustafa Aksakal. He draws on newspapers and other publications to demonstrate that the Ottoman leaders felt they were victims of the international system. They actually hoped for a war in order to be saved from their difficulties. From their perspective, a local war was not only probable but also desirable. The Young Turks dreamed of a war of liberation and independence and they were eager to secure German help for it. The ultimate goal was to stabilize the Turkish international position and to halt its secular decline. However, it is likely that the government in Constantinople neither envisaged nor predicted a general European war, although when this event occurred it was perceived as a great opportunity.

Fred Dickinson analyses reaction in Japan to the war in Europe. His essay shows the surprise felt in Japan when WWI broke out. Once war had broken out, Japanese newspapers and political commentators looked for explanations and found them in the materialistic European culture, in the instability of the balance of power, and finally by conceiving of the war as a racial struggle. In addition to the general explanations, Japanese commentators tended to see Germany as being primarily responsible for the catastrophe. The author also identifies a Japanese culture of profiting from turbulence in Europe in order to make opportunistic gains in East Asia.

The final chapter by Fraser Harbutt examines the perspective of the United States. Americans were generally shocked and surprised by the outbreak of the conflict. It seemed to be an act of European suicide which they had not previously considered to be possible or probable. Developments during the first few months of the war had already made it likely that American neutrality would be pro-Allied and that the US would eventually intervene against Germany. The views from afar demonstrate again that many contemporary observers from inside and outside Europe did not foresee the conflict and that they considered it as a highly improbable event.

All the authors acknowledge that the international system before 1914 was endangered by several developments, prominent among which were armaments competition in the single-minded military understanding of national security. So, was the war unavoidable? Well the authors are rather divided on that. However, WWI did mark an abrupt departure from previous trends in European political culture, not their continuation or automatic outcome. The consensus is that WWI was not inevitable. In the words of a pre-1914 French school book "war is not probable, but it is possible."

Overall, this is an excellent and wide ranging analysis of the factors behind the defective decisions made by many governments in the July crisis. It is to be highly recommended.