Erskine Childers and the Cuxhaven Raid, Christmas Day 1914

Trevor Adams

Perhaps one of the more obscure chapters in the life of Robert Erskine Childers was his involvement in the early war North Sea operations, in the present case his taking part in the raid on Cuxhaven on Christmas Day 1914. If ever the expression the “fog of war” could be applied to an operation, this was it, as we shall see.

Although Childers is often thought of today as being an arch Irish Republican, which indeed was one side of his character, he was also a child of Imperial Britain. He had been to a prestigious public school, Haileybury, and to Cambridge University. He served in the British army in the Boer War with the Honourable Artillery Company (HAC), a reserve unit which is so posh that one can only join by invitation. So, it was little surprise that he returned to the colours, albeit naval ones, in August 1914, in spite of having been engaged in gun running into Ireland for the Irish Volunteers, just a few weeks earlier.

The Cuxhaven raid was a forgotten minor chapter of WWI that was only resurrected in the aftermath of WWII when historians and strategists were examining the seaborne air attacks of WWII such as Midway, Coral Sea, Pearl Harbour and Taranto2. It was only in the post-WWII analysis that the significance of the Cuxhaven Raid was recognised, as being the first seaborne air attack in military history, and also undoubtedly the least successful. Although it is called the “Cuxhaven” raid, in fact its roots lie in the paranoia existing in the United Kingdom (then including Ireland of course) on the threat of aerial attack by so-called Zeppelins. The aim was to attack the airbase that was known to exist to the south of Cuxhaven but without precise information as to its location. In other words, the level of planning of the raid was inept.

In fact, the airship base was at Nordholz, some eight miles (14km) south of Cuxhaven and inland, not on the coast. Today, it is still an operational airfield for the German air force coastal operations, and the site of a wonderful museum on both the era of the airship and more recent aviation history. Indeed, the visitor will find that the term used there is “airship”, as Zeppelins were built at the works in the South of Germany on Lake Constance, on the Swiss border. The northern German airship was the Schűtte-Lanz which used a plywood framework, not the high-tech alloy of the Zeppelin, but had many technological advantages over the Zeppelin. It is a bit like referring to all vacuum cleaners as Hoovers.

Churchill’s ideas for North Sea warfare in 1914-1915

Winston Churchill was First Lord of the Admiralty before and in the early part of WWI. One of his obsessions was German airships – “Zeppelins”. They could do long distance reconnaissance and carry a bomb load, both of which were tasks that were beyond the ability of aircraft in 1914. Indeed, there was widespread paranoia about Zeppelins, and their supposed abilities, in general. In fact, the Germans only had about eight military airships at the outbreak of the war.

As part of the offensives against Zeppelins, the RNAS had carried out an ineffective bombing raid from Belfort in Eastern France on the Zeppelin works at Friedrichshafen on 21st November 1914, which involved infringing Swiss airspace. (RNAS was the Royal Naval Air Service, or, in navy slang, Really Not A Sailor). In fact, the Zeppelin works still exists in Friedrichshafen today, making much smaller airships. There is also a wonderful Zeppelin museum there, on the shores of Lake Constance.

In the period in the lead up to, and just after, the outbreak of hostilities, Churchill had suggested various harebrained attacks in the North Sea. He had ordered studies of possible landings by the Royal Navy on the Dutch, German, Danish and Scandinavian coastlines2. You will note that this involves the invasion of neutral countries. Of the German possibilities, the islands of Helgoland and Borkum were the two being heavily pushed by Churchill in late 1914 and early 1915. However, the greater problem would have been trying to hold enemy territory against what would surely have been massive counter attacks.

In the end, planning the Dardanelles naval attacks and the Gallipoli campaign took over the attention of Churchill and the War Cabinet2.

So, the raid on the airship base at Cuxhaven was thought up as being a way to forestall Zeppelin attacks on the UK, or indeed Entente forces on the Western Front, without committing ground forces. It was spurred on by the German navy attacking Hartlepool, Whitby and Scarborough on 16th December 1914. There was felt to be a need to “do something”.

Erskine Childers’ recruitment

On the outbreak of WWI, Churchill needed people who knew the Dutch and German coastline intimately. He asked Sir Henry Oliver, the Director of Naval Intelligence to find someone appropriate. Oliver failed in his attempt to recruit Gordon Shephard, as he had already left for service in the RFC in France, as of course part of the BEF. Oliver’s staff then tried to trace Erskine Childers – but why him? The answer lies in Childers’ sailing exploits.

Erskine and his brother Henry started sailing seriously when they bought a cutter, The Shulah, in 1893. Various localised sailing adventures with that and its successor Mad Agnes followed. In October 1897, he set off in another yacht, The Vixen, intending to pick up his brother and a friend at Boulogne and head West. However, the weather was not promising, so they headed East to the Friesian Islands on a journey which would be the inspiration for his only novel, The Riddle of the Sands. In 1905, he took delivery of The Askard, a wedding present from his father in law, Hamilton Osgood. Erskine and Molly Childers sailed The Askard to the Baltic in 1906 and 1913 (and elsewhere in between but the sailing records are patchy at best5). Certainly, the little channels of the Friesian islands and the Baltic archipelagos provide a wonderful sailing experience for the yachtsman. By August 1914, Childers had a detailed knowledge of the Dutch and German coastlines. That was his value to the Royal Navy.

So, Oliver’s staff sent out telegrams to trace Childers, one even being sent to the headquarters of the Irish Volunteers in Dublin! In early August, Erskine Childers reported to the Admiralty4 to be interviewed by his old friend Captain Herbert Richmond, Assistant Director of Naval Operations. He emerged a few hours later as a Lieutenant in the RNVR (Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve), never having previously having had anything to do with the Royal Navy. The upper class “old school tie” system was alive and well. (If you are not up to speed on naval ranks, a RN Lieutenant is equivalent to a captain in the army).

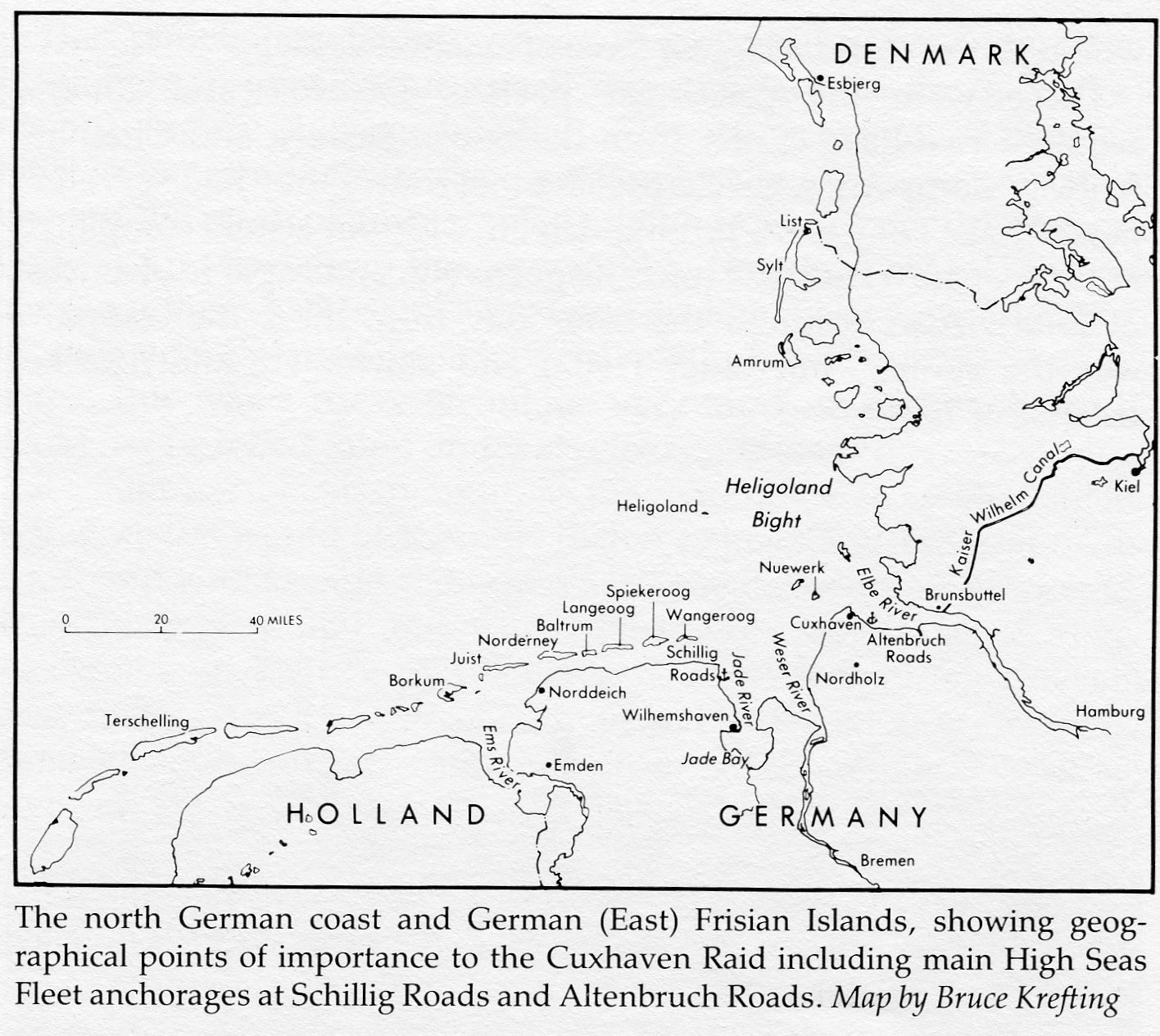

Geography of the German coast

Cuxhaven is a harbour town at the mouth the River Elbe, which leads up to the port of Hamburg, and guards the access to Hamburg. The island of Helgoland lies some way off the coast. Both were naval bases in 1914, although Wilhelmshaven was the major base on this stretch of coast.

The coast is flat with extensive mudflats, called Watt in German, hence the name of the area of sea as the Wattenmeer – “the sea of mudflats”. Just off Cuxhaven is the island of Neuwerk, some 12 km out, which can easily be reached on foot at low tide. Indeed, it is possible to walk out for 20km. So, if you can walk out that far, the sea is so shallow that it is impossible to bring large naval vessels close in, save for the defined shipping channels which back in the day would also have been well defended. That coupled with the flat, featureless coastline and the flat trajectory of high velocity shells from naval heavy guns would have rendered an effective coastal bombardment very difficult.

The flat expanse of the Wattenmeer at Cuxhaven, with the bundles of twigs to mark the walking route out to the island of Neuwerk

Erskine Childers’ naval service

Following his being recruited by Captain Oliver in early August, Childers was immediately given a small office in the Admiralty and asked to draft a plan for the invasion of the German island of Borkum, which he duly did, on his own, in three days4. The plan was quietly stifled by the War Office and senior figures in the navy who regarded the idea as idiotic and amateur. Considering that the Admiralty had given the task to an amateur who knew nothing about offensive seaborne operations, this is hardly surprising. It was another one of Churchill’s schemes which was quietly mothballed, never to see the light of day.

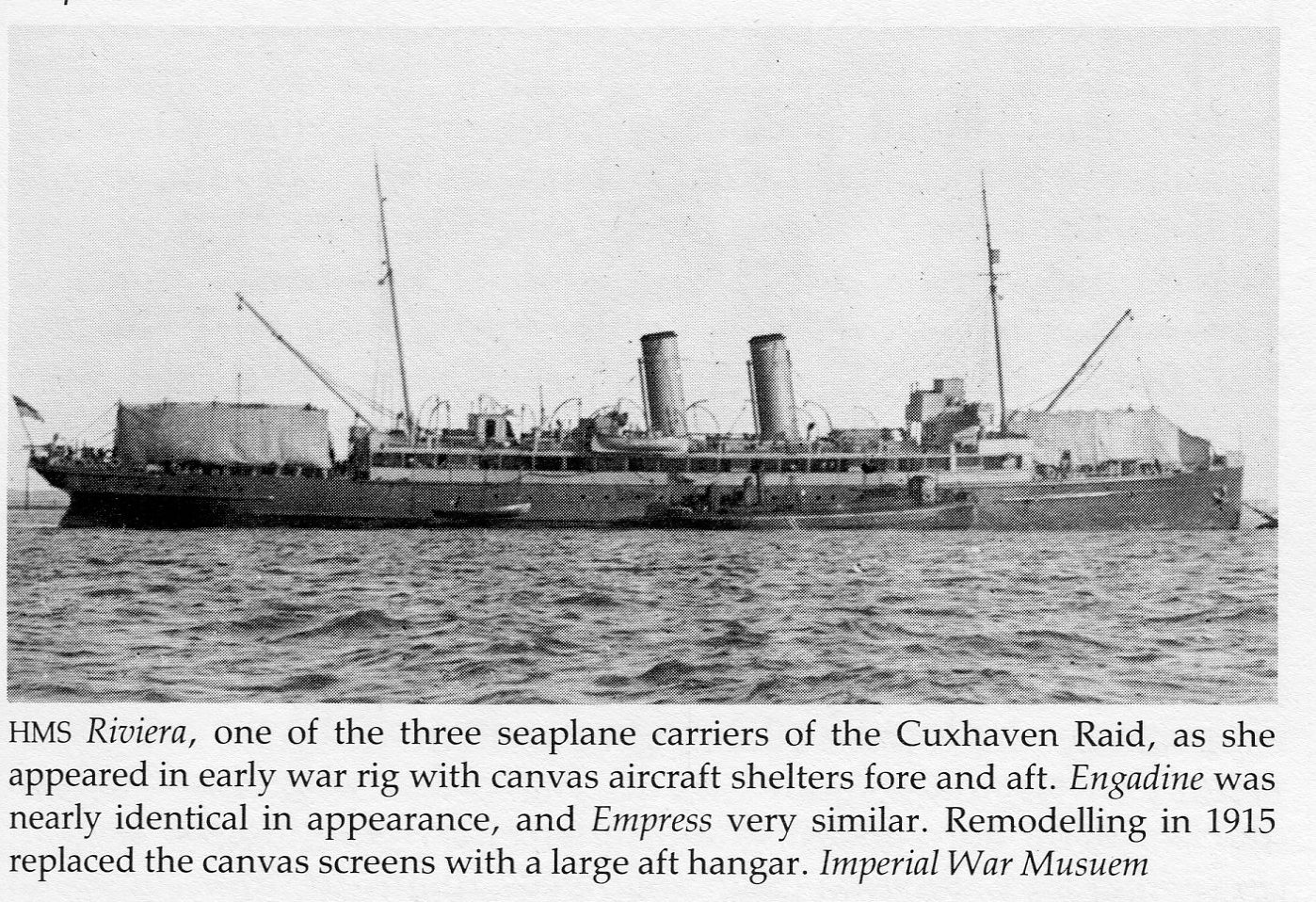

On 18th August 1914, Erskine Childers reported to the naval air base at Felixstowe, on the East coast. Two days later, he was attached to HMS Engadine, at the rather advanced age of 44. He was referred to as “uncle” by his fellow crew members. His primary function was to teach navigation to pilots and observers, using both charts and the stars. He also volunteered to be the ship’s intelligence officer.

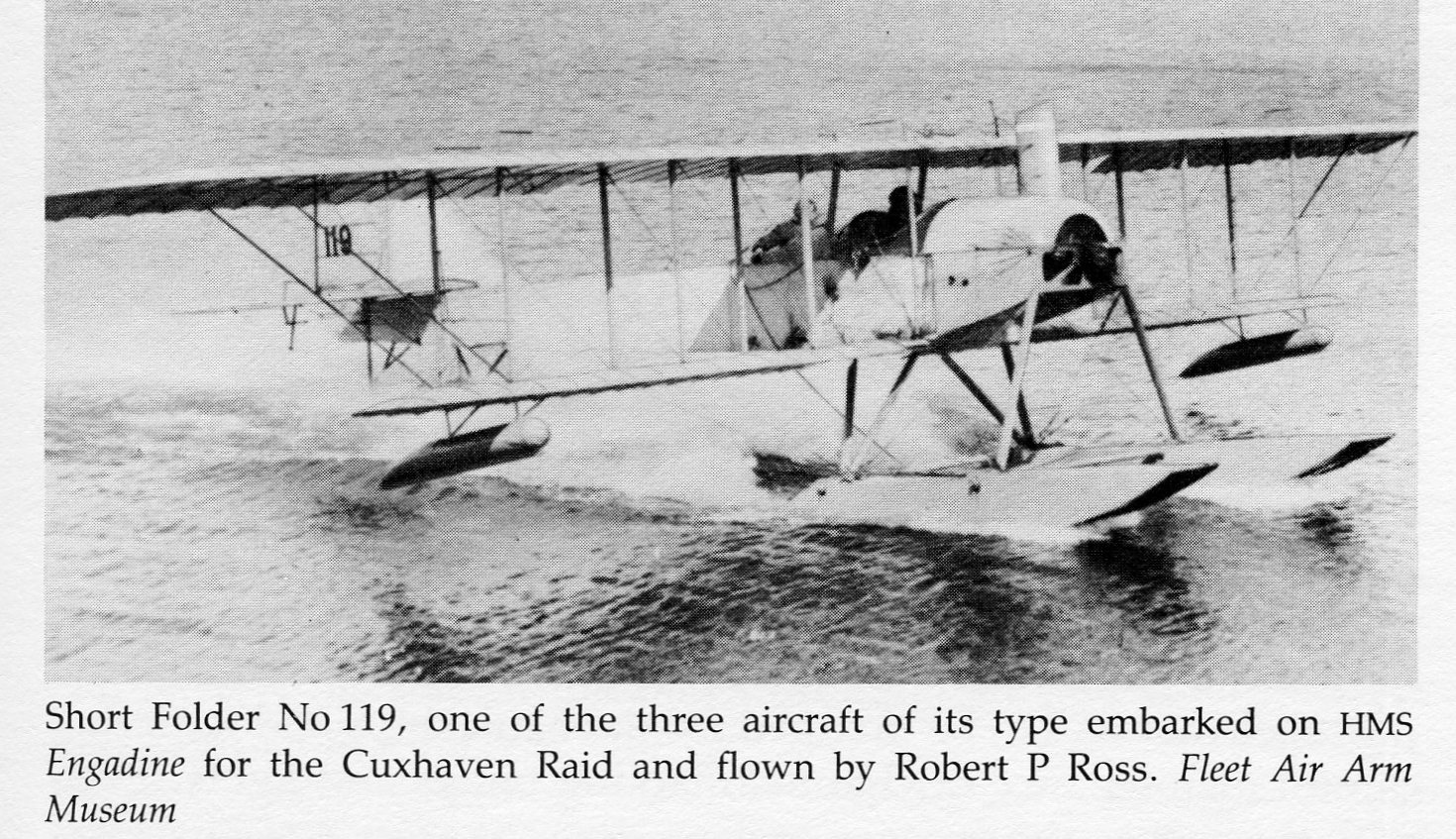

This ship was literally an aircraft carrier, ie it carried aircraft, but at this stage in naval aviation the planes were seaplanes which had to be lowered on to the sea for take-off and then recovered from the sea, when they hopefully returned from their mission. It had been converted from a cross-channel ferry, in a process taking all of a week.

Childers is recorded as having been rescued along with his pilot when they had to land their seaplane off Hartlepool in late September. So, he was obviously involved in flying at an early stage of his naval career.

The Cuxhaven Raid

The officer in charge of the raid was Squadron Commander Cecil Malone. Of Childers input, he said:

The valuable assistance rendered by Lieutenant Erskine Childers RNVR, whose knowledge and experience connected with the navigation of the German coast proved invaluable in instructing the pilots.

And he referred to:

The energy expended by him in preparing charts and collecting topographical data.

Whilst one of Childers’ biographers has suggested that he acted as chief observer in the air and in effect, lead a close formation of aircraft, this is not what happened in 1914. Instead, the aircraft made their own way. There were up to 150 ships involved in various roles, all to facilitate the delivery of just 81.5 lbs (39kgs) of explosives (though in fact only a fraction of that was dropped in anger by the aircraft).

The plan was to launch the planes from a point north-east of the island of Helgoland and fly south west, to make a landfall in the Cuxhaven area. They were then to “seek out” the airship base. On their way back, they were to carry out reconnaissance missions, which were to find out whether:

- the Elbe lightships were still in place

- there was a channel through the minefield at the mouth of River Jade and, if so, whether there were buoys visible

- the exact anchorages of ships in Schillig Roads (near Wilhelmshaven) could be identified

- the number and types of ships in Wilhelmshaven harbour could be identified

- the location of the boom guarding Schillig Roads could be seen, and

- there were suitable targets in Schillig Roads for the British warships to fire at.

After the attack on the airship base and the reconnaissance, the planes were to fly westward, and follow the Friesian Islands as far as Norderney. They were then to turn north between Norderney and Juist to a point 20 miles north of Norderney where the carriers were to be waiting. Aircraft of this period did not carry radios. As well as surface ships, submarines were deployed to the area to act as rescue vessels for planes which had to land without finding their mother ship.

What the aircrews didn’t see – the Drehhalle (rotating hanger) at Nordholz, which could turn through 360o, to mitigate the effects of crosswinds when moving the airships in or out. This was to avoid hitting the fragile airship on the hanger doors. A complete rotation took an hour.

This was all happening on virtually the shortest day of the year on a foggy North Sea coast in the middle of the winter. On 25th December 1914, there was indeed fog along the coast. This led to uncertain navigation by the aircrews, and ultimately uncertainty about where they had been and what had happened. Consequently, the bombing missions, such as they were, had no success. From the German records, two veterans who had been stationed at the airship base at Nordholz at the time recall a British plane appearing out of the mist and it dropping two bombs which missed the hydrogen gasometer by 100m or more1. The anti-aircraft batteries fired at it vigorously. (This, incidentally, was the only occasion that bombs were dropped on or near Nordholz during the whole war). However, none of the British crews believed that they either had found the airship base or bombed it, however inaccurately.

So, who was the phantom pilot? Well, Gaskell Blackburn reported that he had dropped two bombs on ships in Wilhelmshaven harbour, and had been heavily fired at by anti-aircraft batteries. However, the Wilhelmshaven archives do not record any bombs falling on the harbour or the town on 25th December. Furthermore, there were no anti-aircraft batteries in the harbour or the town1. So, Blackburn’s plane seems to be the most likely candidate for the “phantom” attacker. If so, he was the only pilot to find the Nordholz airship base, even if he never realised it!

Flight Lieutenant Charles Edmonds was the only flier to undoubtedly bomb German warships. He dropped two bombs on the light cruisers Stralsund and Graudenz in the River Weser. The German records state that one was wildly inaccurate and the other was 200 meters away off the Graudenz beam, putting up a 10-meter column of water. Edmonds later carried out the world’s first torpedo attack from a plane, in 1915, and ultimately became an air vice marshal in the RAF3.

Another “first” for the Cuxhaven raid was an attack on a warship from the air. Edmonds certainly did so, but in addition the German airship L5 which was 20 sea miles north of Nordeney attacked the Royal Navy. It spotted a British submarine rescuing the crews of three planes. The submarine then dived. A number of RN surface ships were spotted going to recover the aircraft floating on the sea. To hinder this, L5 dropped two bombs without hitting the submarine or the surface ships.

Childers was the observer for Flight Commander Cecil Kilner in Short seaplane number 136. (Not all the planes carried observers, not least to save weight). In their joint report, they state that they reached the coast at 8.17am at an altitude of 1000 feet (330 meters). They encountered fog and had to drop to 200-300 feet (70-100 meters) in order to see the ground, as that is how they navigated.

“The fields were under hoar frost and the atmosphere was dull and dark”.

“Shortly after crossing the coastline, the engine began to misfire, possibly due to the extreme moisture of the atmosphere or to over lubrication.”

This problem continued for rest of their flight, dropping the revs from 1300 to 800 at times. They believed that the airship base was “a few miles” to the east of the village of Cappsiel. They located a village that they believed to be Cappsiel, and then searched east and south of it, without success3. The task was abandoned as the engine continued to misfire, and they reached the coast near the River Jade. They headed west-north-west to Schillig Roads. They were heavily fired at but Childers managed to identify various warships, albeit the seven battleships he reported as dreadnought classes Deutschland and Braunschweig were in fact pre-dreadnoughts, as the dreadnoughts in question were at Brunsbűttel at the time. Their report states that they did not drop any bombs on these vessels “as a hit did not seem practicable”. They flew to the island of Wangeroog to attack a submarine base but could not find it. At 9.40am, they headed north from Nordeney and were recovered by one of the aircraft carriers.

The Kilner/Childers plane was the only one to be able to do any of the reconnaissance tasks, and, even then, they were heavily shackled by poor visibility. They were able to establish that:

- there was no swept channel leading to the River Jade

- there was no boom defending the harbour at Schillig Roads, and

- no worthwhile targets were there.

None of the planes scouted the main naval base at Wilhelmshaven.

There were attacks on the Royal Navy ships by the airship L5 and by surface ships and submarines. However, the only shots actually fired by one surface ship at another was the German battleship SMS Wettin firing on a German trawler. In the end, the British losses were four men lost at sea, due to heavy weather on the following day. One of the sailors was from HMS Caroline, now a museum in Belfast. The weather was so bad that the ships were ordered to return to port. The navy lost four seaplanes and had some ships temporarily disabled because of the damage inflicted by the bad weather – two battleships, three destroyers and a submarine. The British flotilla was protected, as the German coast had been, by typical North Sea foggy weather.

There were various exaggerated claims for the effects of the Cuxhaven raid, including the myth that the battlecruiser Von der Tann had been damaged in a collision3, as it was not present in the battle of the Dogger Bank, four weeks later. In fact, the Von der Tann was in drydock for planned maintenance at that time, and could not be extricated when the operation was hastily rescheduled to take advantage of a break in the weather.

One major lesson on the efficacy of airships or aircraft attacking ships which emerged from the Cuxhaven raid was, to quote Commander Reginald Tyrwhitt3, that “given ordinary sea room, our ships have nothing to fear from seaplanes or Zeppelins”. That held good for the rest of WWI, but the tables were turned in WWII, when warships became very vulnerable to air attack.

A forgotten lesson of the raid was that submarines can be used to rescue downed aircrews in a concerted attack on the enemy. The US Navy did do this to good effect in the Pacific campaign in WWII, one notable rescued pilot being President George HW Bush, as he became later in life.

What did Erskine Childers do next?

In summary, his naval career was as follows6,7:

August 1914 - March 1915: HMS Engadine

March 1915 – December 1915: HMS Ben my Chree (another seaplane carrier, originally a Manx ferry). Service in Gallipoli and Egypt.

December 1915 – March 1916: Coastal Motor Boats in the North Sea

March 1916 - July 1917: Intelligence officer, the advanced seaplane base, Dunkirk

July 1917 – April 1918: Secretariat of the Irish Convention, Dublin

May 1918 – September 1918: Naval section of air intelligence at the Air Ministry

September 1918 – November 1918: Intelligence officer with no. 27 Group HQ, RAF Bircham Newton, working on the planned air raid on Berlin

November 1918 – December 1918: In Belgium, preparing report on bomb damage

March 1919: Discharged from service

He was promoted to Lieutenant Commander RNVR in December 1916 and was redesignated as a major when the RAF was formed in March 1918. He received a Mentioned in Despatches for the Cuxhaven raid in 1915, and a DSC in 1917 for his work in Egypt.

So, the arch Establishment figure of 1914-1918 became the hardline Irish Republican in 1919 who would not accept the Treaty in 1921. Many others have written about him and his Irish activities, doubtless more authoritatively than the present author ever could. However, I remain fascinated by his role as surely the oldest new lieutenant ever to grace an RNAS plane.

References

- Hein Carstens, Schiffe am Himmel, Verlag Heimatbund der Mȁnner von Morgenstern, Bremerhaven, 1997.

- Paul Halpern, A Naval History of World War I, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1994.

- RD Layman, The Cuxhaven Raid, Conway Maritime Press, London, 1985.

- Leonard Piper, The Life and Death of Erskine Childers, Hambledon and London, London and New York, 2003.

- Hugh and Robin Popham, A Thirst for the Sea, Stanford Maritime, London, 1979.

- The Private Papers of Lieutenant Commander RE Childers, DSC, RNVR, Imperial War Museum.

- Service records of Robert Erskine Childers, ADM-273-5-8, ADM-273-19-232, ADM-337-117-202, ADM-337-124-493, AIR-76-85-171, National Archives, Kew, London.

The photographs of the HMS Riviera, Short plane and the map are from the Layman book, which I would recommend to anyone seeking the detail of the Cuxhaven Raid.

The Riddle of Erskine Childers by Andrew Boyle deals with his Irish adventures.