An unknown chapter of the adventurism in Russia – the Baltic campaign

In monarchies, there is the saying “the king is dead, long live the king”, ie the new king automatically succeeds to the throne. Well, the British Foreign Office did much the same thing as regards WWI. On 11 November 1918, the rest of Britain may have been celebrating the end of the war but the Foreign Office was telling the Admiralty to send ships to the Baltic to support independence for the Baltic “provinces”. They were to oppose the Russian Bolsheviks, who were the new enemy. However, there was to be no interference in the “internal affairs” of the new Baltic countries. A key question, which the Foreign Office did not answer was, do we fire on Russian ships? In fact, the naval task force under Rear Admiral Cowan and the Admiralty under Admiral Wemyss made up their own pragmatic approach as matters progressed.

There were no post-WWI treaties until June 1919 at the earliest. So, the armed forces on both sides were controlled by the terms of the Armistices. Article XII of the Armistice with Germany reads as follows:

“All German troops at present in territories which before the war formed part of Russia must likewise return to within the frontiers of Germany as above defined as soon as the Allies shall think the moment suitable, having regard to the internal situation of the territories”

Well, that looks as if the German army has to go back to Germany, doesn’t it?

In December 1918, the RN reached Riga in Latvia. Captain HH Smith, the senior RN officer issued the following instruction to the German general in charge of the Baltic Division, von der Goltz:

The Germans are to retain sufficient force in the district to hold the Bolsheviks in check and are not to permit them to advance beyond their present positions

In other words, the German army are our new friends! The instruction rather surprised the German high command.

One of the first actions of the Royal Navy was for HMS Ceres to shell Latvian defectors (Bolsheviks). This is an interesting interpretation of the proviso not to interfere in the internal affairs of the new Baltic countries.

So, who is who in the Baltic?

There were two White armies (ie Tsarist) under Russian Generals Yudenich (North Western Army) and Prince Bermondt-Avalov (Western Army) photo left. Yudenich’s army had 40,000 German Freicorps (the Eiserne Division and the Deutsche Legion).

The German Ostsee division under General von der Goltz is there, occupying Latvia, having freed Helsinki of the Finnish Bolsheviks.

As well, there were reservists known as Baltische Landeswehr in Latvia, who were ethnically German. Bizarrely, in July 1919 the British thought they would be better with their own man in charge of the Landeswehr. So, an up and coming star was put in charge of this German unit – Lt Col the Hon Harold Alexander, later known as Field Marshall Lord Alexander of Tunis, photo right.

The Latvian National Army came into existence in July 1919, and the Lithuanian Army in May 1919. The Estonian national army was formed in May 1919 and was largely composed of Baltic Germans.

The Polish army was also in the region, though the issue was on whose side they were. Certainly, they fought against the Russian Bolsheviks but also against the Lithuanians, at various stages. The whole situation in the Baltic States was immensely complex. One facet of this was that the Russian White armies wanted to keep Russia intact and so opposed independence for the Baltic States. The British government had lent Yudenich six tanks and their crews. However, the Royal Navy was tasked with helping Baltic independence. So, at least in theory the British army and the Royal Navy were on opposite sides.

The opposition to the British in the Baltic region comprised:

- the Russian Red Army which included Estonians and Lithuanians

- the Army of Soviet Latvia, comprising Latvian riflemen and an international division, and

- the Bolshevik Estonian Riflemen.

But all the groups were highly ethnically mixed.

Events in this region were highly complex.

The following gives an idea of some events happening in this period.

On 22 Nov 1918, there was a Red army assault on Estonia and Latvia. This was halted by a combination of the

- Estonian army,

- Finnish volunteers

- Kuperjanov partisans (Estonian irregulars), and

- Baltische Landeswehr (ethnically German)

On 2 Jan 1919, the Latvian Riflemen (Bolshevik) take most of Latvia. On 22 May 1919, the Freicorps take Riga, capital of Latvia, and kill thousands.

Vilna (today Vilnius) was occupied by the Poles again in 1920.

In October1920, there was a Latvia – Lithuanian stand-off in llukste but by this time the borders of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia were pretty much consolidated. In March 1921, there was the Soviet-Polish treaty which brought to an end the Polish-Soviet war, see below, and settled the borders until WWII.

All military entities used terrorisation. It was an awful time to be a civilian in these regions.

Above: one of the more bizarre episodes. This is the Royal Irish Karelian Regiment, formed by eccentric British Officer Lt Col Philip Woods (from The King of Karelia by Nick Barron). The cap badge is a green shamrock on an orange background, to be totally politically neutral in Irish terms! (Imperial War Museum)

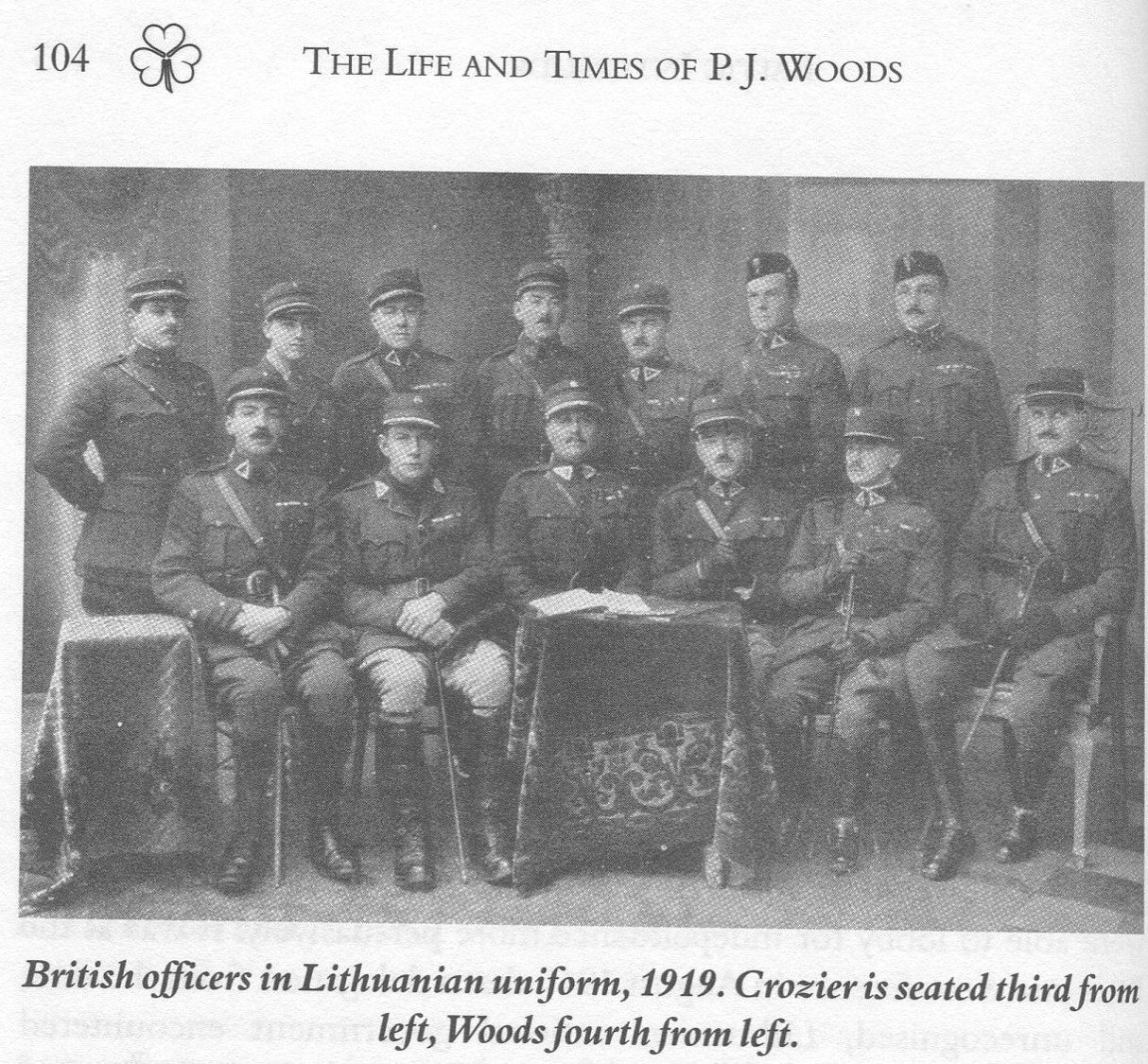

The photo below is from the same source and is of “Lithuanian army officers”, all of whom are in fact British army officers. (Nick Barron, The King of Karelia)

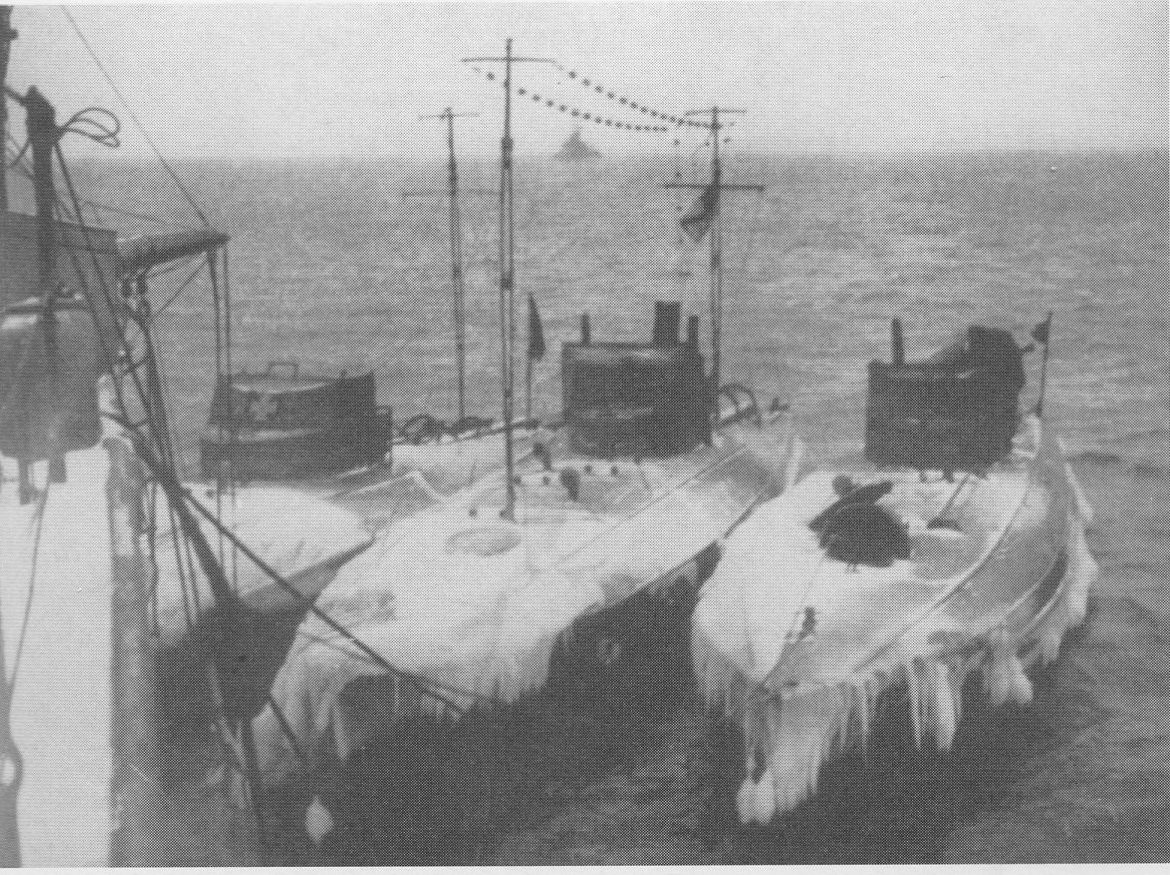

HMS Caradoc at Reval, now Talinn, in December 1918 (Imperial War Museum)

Gulf of Finland 1919, showing Reval which the RN used as one base, the Russian base at Kronstadt on Kotlin Island outside Petrograd (St Petersburg). Helsingfors is now Helsinki (from Geoffrey Bennett “Freeing the Baltic”, as is the photo below of coastal motor boats).

Royal Navy VCs

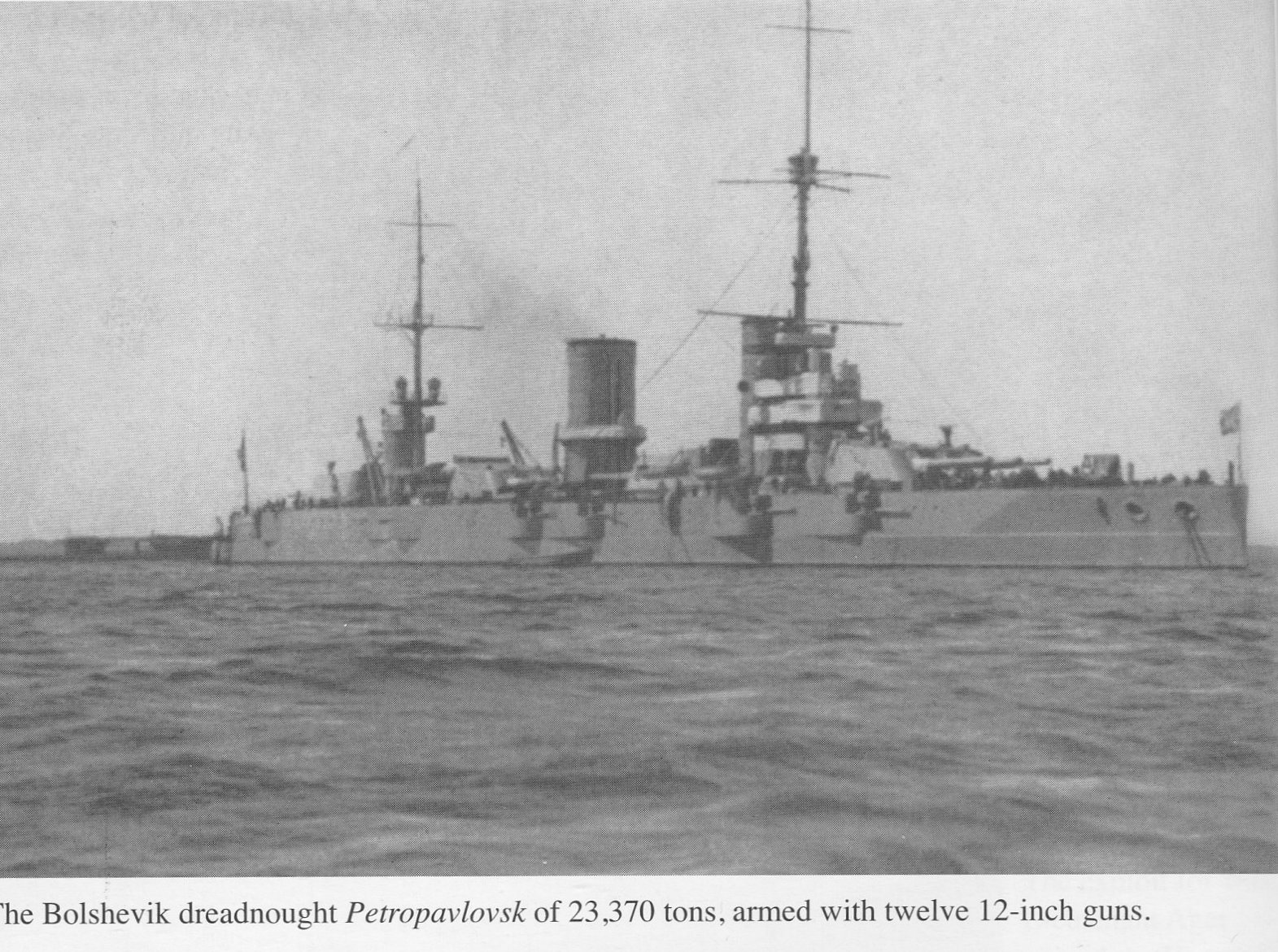

On 18 August 1919, an attack was mounted by coastal motor boats of the Royal Navy on the harbour at Kronstadt, outside St Petersburg. This was a pre-emptive strike, as Admiral Cowan was deeply concerned about the presence of the dreadnought battleship Petropavlovsk, and to a lesser extent of the older Andrei Pervozvanni. The Royal Navy only had medium cruisers in the Baltic, and indeed an attempt by the French to deploy one of their battleships had not gone well when it grounded in the confined waters of the Gulf of Finland. In the RN attack, both of the key targets were sunk, albeit in a harbour so they were later salvaged. VCs were awarded to three RN officers, all of whom survived and reached high rank later in their careers. They were:

- Augustus Agar (Commodore)

- Claude Dobson (Rear Admiral)

- Gordon Steele (Captain)

The main target - the Petropavlovsk (from Geoffrey Bennett, “Freeing the Baltic”)

The main target - the Petropavlovsk (from Geoffrey Bennett, “Freeing the Baltic”)

More Treaties

The fighting in the Baltic region was brought to an end in a series of treaties between various of the belligerents, and as these were genuine agreements between belligerents, unlike the Paris set of ultimate treaties, they had a good chance of working.

So, in 1920 there the treaties of:

- 2 February Tartu : Estonia – Soviet Russia

- 12 July Moscow: Lithuania – Soviet Russia

- 11 Aug Riga: Latvia – Soviet Russia

- 14 Oct Tartu: Finland – Soviet Russia

In March 1921, the Treaty of Riga was signed between Poland and Soviet Russia.

In 1922, the Treaty of Rapallo was signed between Germany and Soviet Russia. In 1926, the Treaty of Berlin was signed between Germany and all the Soviet republics, in effect confirming the Treaty of Rapallo.

British Salonika Force no more?

Let us look at the remarkable number of British forces in and around the Middle East in 1919.

After the Armistice with Bulgaria on 30 September 1918, the British Salonika Force (BSF) moved into Bulgaria. They were involved in the transfer of South Dubrudja, a Bulgarian speaking area, to Romania. (After WWII, the area was returned to Bulgaria.)

On 14 Dec 1918, General Milne moved his HQ to Constantinople from Thessaloniki. The BSF becomes the “Army of the Black Sea” on 9 Jan 1919. There were deployments at Batum on the Black Sea (Armenia) and Tiflis (Georgia). Milne’s troops were stretched from Greece into the Caucuses. Not only did he not have any new troops but his existing soldiers were being demobbed and sent back to the UK.

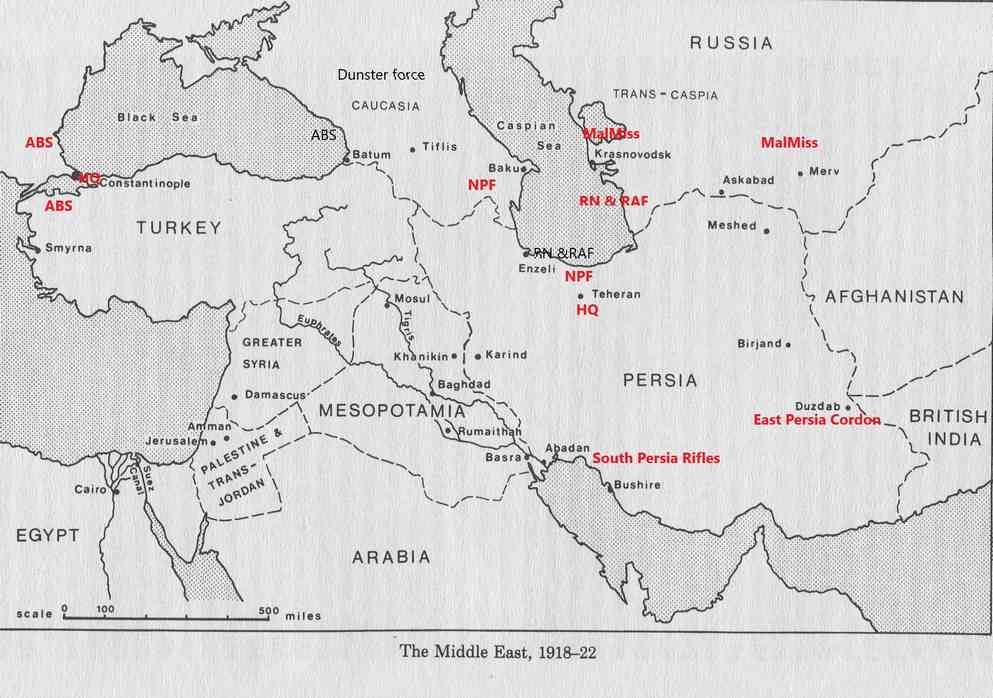

Mesopotamia had largely been taken by Sir William Marshall’s Mesopotamia Expeditionary Force by the time of the Ottoman collapse in October 1918. This force was accompanied by the variety of semi-autonomous units – see the map below and the description of the forces.

The Royal Navy had patrol boats on the Caspian Sea, and the RAF used seaplanes there. There were army detachments in what is today Turkmenistan. Remember this is the region which Curzon wanted to have as a buffer zone to protect India (but from whom?). So, the forces in this region included:

The Royal Navy had patrol boats on the Caspian Sea, and the RAF used seaplanes there. There were army detachments in what is today Turkmenistan. Remember this is the region which Curzon wanted to have as a buffer zone to protect India (but from whom?). So, the forces in this region included:

- Dunsterforce was in Transcaucasia toward the end of WWI to stop the oil wells falling into Ottoman or Russian hands, which they failed to do, unsurprisingly as it was an ad hoc formation of some 450 soldiers. (It was named after its leader Gen Lionel Dunsterville).

- Norperforce was in Northern Persia, hence its name, and up into Transcaucasia.

- Malmiss, supposedly an intelligence gathering operation of some 500 men of the Indian army, was at Krasnovodsk and Merv in what is now Turkmenistan, and Meshed in NE Persia. (Malmiss is Malleson Mission, after its leader, Gen Wilfrid Malleson).

- The South Persia Rifles, a scratch force of British, India and local forces was, as the name implies, in South Persia.

- The East Persia cordon was an Indian army force protecting the Indian frontier.

Dunsterforce, Armenia (Imperial War Museum)

Dunsterforce, Armenia (Imperial War Museum)

Memorial to British forces in Baku, Azerbaijan (CWGC). Those commemorated in Batumi (Georgia) are now on a screen wall erected in 2014 in the CWGC cemetery. The Haidar Pasha monument in Istanbul lists those killed in South Russia and also in Transcaucasia (and so overlaps somewhat with the aforementioned memorials).

Memorial to British forces in Baku, Azerbaijan (CWGC). Those commemorated in Batumi (Georgia) are now on a screen wall erected in 2014 in the CWGC cemetery. The Haidar Pasha monument in Istanbul lists those killed in South Russia and also in Transcaucasia (and so overlaps somewhat with the aforementioned memorials).

The Middle East –how to create a flashpoint

This was a secret agreement conclude between Britain and France, long before the war ended, in 1916 over territory which they did not occupy or own! Its existence was revealed in 1917 by the Russian Bolsheviks. The provisions were varied in the treaties of St Remo and Lausanne. So, the area of Northern Mesopotamia (Iraq today) around Mosul became British, not French, and Palestine, which was supposed to be an international zone, became British. These were practical variations as the British occupied these areas and were not minded to give them to the French.

The changes led to French resentment, and rivalries in the region. The French did not help Britan in the 1936-39 Palestine unrest, and French aided Zionist terrorist groups in Palestine in the 1940s.

In summary, the French ended up with control over Syria and the Lebanon. The British had control over Iraq, Trans Jordan and Palestine.

One of the key problems especially in this region was the shortage of troops. So, the system of so-called “air policing” was used. In effect, this was using aircraft to bomb insurgent forces but more often civilian areas. General Sir Aylmer Haldane, GOC Mesopotamia and Persia said:

“I do not consider that this country can be held and administered by a form of terrorism, which would involve the death by bombing of women and children”

Hugh Trenchard, head of the RAF, was quoted as having said in 1924 that the technique was most effective, as one could be sure to kill at least one third the inhabitants of the village that was being bombed.

So much for morality. In effect, the shortage of troops had lead the government into severe repressive measures. Self-determination was not much in evidence in Europe either, and for people of colour their efforts and loyalty in WWI were rewarded by the return of colonialism in a form that was at least as oppressive as before the war.

Europe – Poland

Poland is an example of the shifting borders of Europe in the 20th century. It had not existed as a country for 200 years. The various Paris treaties settled little in this area. Poland had the “blue army” which was ex-patriate Poles who had fought with the French, and Polish contingents from various of the former belligerents. Poland fought wars from 1918-1921. For example:

- November 1918 – against Ukrainian troops in Galicia

- Spring 1919 – against German Freicorps in Upper Silesia, a disputed region where there was in fact a plebiscite in 1921, as a rare example of self-determination; and

- Spring 1919 to late 1920 – against Soviet Russia.

The major conflict for Poland was the Polish-Soviet war:

- 1919 - Poles attack Belarus

- May 1920 – Poles capture Kiev

- June 1920 – Red army pushes Poles out of Kiev

- Red army advances through Belarus and Western Ukraine

- August 1920 – Red army close to Warsaw

- General Pilsudski attacks and forces the Russians to retreat, known as the “miracle on the Vistula”. (The Vistula is a river). French forces were in Warsaw under General Maxim Weygand, with staff officer Charles de Gaulle (to whom there is a statue in Warsaw today).

Lvov after the siege of 1920 (also Lviv or Lemburg, Imperial War Museum)

In March 1921, the Treaty of Riga between Poland and Soviet Russia was signed. Soviet Russia was in a weak position, not least as Poland occupied a huge swathe of territory. In the treaty, Poland got western Belarus and western Ukraine. This meant that four million Ukrainians, two million Jews and one million Belarussians were catapulted into the Polish state without having any say in the matter. These areas were heavily disputed for years to come, and were returned to Soviet Russia post WWII.

The blue line is the Polish border from 1921 to 1945. The blue area is the area of Belorussia and the Ukraine occupied by Poland. The red line is the border from 1945 until the present. The buff coloured area is regions transferred to Poland from Germany after WWII.

Poland, in effect, moved westwards, post WWII. The western land were areas expropriated from Germany by the Allies. The Polish population was expelled westwards from now Soviet areas in the east, and the German population was expelled westwards from the now Polish territories.

The compound countries – recipe for divorce?

The two obvious candidates for this description in Europe were Czechoslovakia and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovene (KSCS) which was Yugoslavia from 1929. Neither of these countries still exists – they have fallen apart.

Czechoslovakia was created from the Austro-Hungarian provinces of Moravia and Bohemia. Slovakia was added on by default and much to the surprise of the Slovaks whose consent was not sought by the Allies. The Czech politician Tomas Masaryk had been marooned in Russia after going to visit the Czechoslovak legion there. He had to exit via Vladivostok and then across the USA. There, he met Woodrow Wilson who had been lobbied by Czech ex-patriates into putting Slovakia into the new state.

Again, there was fighting between the new countries. The town of Teschen was disputed between Czechoslovakia and Poland. The supposed solution was to divide it between the two countries.

There was a Czech invasion of Slovakia in 1919 and defeat by Hungarian red army. Czech troops also moved into the Sudetenland, an ethnic German area, and there was a massacre of ethnic German protestors on 4 March 1919. There was looting of ethnic German and Jewish property in Prague at this time as well. So, again strife within, and across, borders. Eventually, Czechoslovakia did function as a democracy in the interwar years, a virtually unique achievement for the emergent countries in Europe.

Serbia moved into the areas of Banat, Backa, Baranja, southern Hungary, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Dalmatia, Montenegro, Croatia, and Slovenia, in effect much of what became the KSCS. In 1919, Serbs and Slovene troops occupied Carinthia. In a rare referendum in October 1920, Carinthia voted to be in Austria.

The KSCS structure looks problematic, just from its name, letting along the fact that the Muslim population was not even mentioned. Its structure was never settled. It was only through centralised power, royalist before WWII and communist post-WWII, that it was stable. When Tito died and the central power fell apart, so did the country in a bloody disaster. So, the lesson is that shoving populations into countries with other ethnic groups, without anybody’s consent, is a recipe for disaster. On another continent, that is what happened with Iraq.

Overall, the effects of the various treaties on European cities and countries was to make them less ethnically and religiously mixed than in 1914, at least partly because of the movements of populations. This process continued in the aftermath of WWII, so that the countries that we see today are much more homogeneous than the mixed societies that existed in Europe pre-1914. Is this progress?

By 1923, where have we got to?

The worst fighting is over but instability remains. The Middle East is still a case in point today.

From the British side, the CWGC cemeteries were “finished” by this time, but many memorials had not yet been erected.

The Lausanne Treaty between Turkey and the Allies was concluded. As this was a genuine treaty between former belligerents, it held.

The Treaty of Locarno (1925) was signed between France, Germany, UK, Italy, Belgium guaranteeing the western borders of Germany, and arbitration with Poland and Czechoslovakia over disputes concerning the eastern borders. This again was a “real” treaty between the involved parties which was therefore likely to be effective.

We now have a smaller UK. The UK had, by January 1922, lost a considerable chunk of its land area by the creation of the Irish Free State. (Incidentally, the last British troops did not leave Ireland until December 1922).

But has WWI ended? One historian opined that the fall of the Berlin wall in 1990 was the end of WWI. Maybe that is the case in Europe, but I doubt that many in the Middle East would agree.

End piece

What are we left with? Well, commemoration is perhaps a key matter uppermost in our minds. The photo below is from 2016 in Tallinn, with two RN personnel along with Estonian military laying wreaths in memory of the RN personnel killed in the Estonian war of independence (CWGC).

References

Books

Nick Baron, The King of Karelia, Francis Boutle, 2007

Geoffrey Bennett, Freeing the Baltic 1918-1920, Pen and Sword Maritime 2017

Norman Davies, Vanished Kingdoms, the History of Half-Forgotten Europe, Penguin 2012

Sir James Edmonds, The Occupation of Constantinople 1918-1923, Imperial War Museum Naval and Military Press 2010

Robert Gerwarth, The Vanquished, Penguin Random House 2016

Keith Jeffrey, The British Army and the Crisis of Empire 1918-1922, Manchester University Press, 1984

Alan F Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, Four Courts Press 2004

The books by Robert Gerwarth and Keith Jeffrey are the outstanding reference works for this period. Norman Davies’ book is an excellent work on the changes in European countries and borders over the centuries.

Internet

Added information has been filled in by the wonderful articles from an international panoply of authors in the International Encyclopaedia of the First World War, 1914-1918 online, Freie Universität Berlin. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/ To name but a very few of the 1000 or so articles:

Alan Sharp, The Paris Peace Conference and its Consequences

Annamarie Sammartino, Paramilitary Violence

Ceslovas Laurinavicius, Polish-Lithuanian Border Conflict

Christophe Declerq, German communities and their expulsion (Belgium)

Ian Packer, Lloyd George, David

James E Kitchen, Colonial Empires after the War/Decolonisation

Jaroslaw Centek, Baltische Landeswehr

Jaroslaw Centek, Polish Army in France

Jaroslaw Centek, Polish-Soviet War 1920-21

Jens Boysen, Polish-German border conflict

Katrin Boekh, Crumbling of Empires and Emerging States: Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia as (Multi)national Countries

Klaus Richter, Baltic States and Finland

Leonard V Smith, Post-war treaties (Ottoman Empire/Middle East)

Miklos Zeidler, Trianon, Treaty of

Nur Bilge Criss, Occupation during and after the War (Ottoman Empire)

Oksana Dudko, Polish-Ukrainian conflict over Eastern Galicia

Pawel Brudek, Polish Legionnaires Union

Pawel Brudek, Polish War Myths (East Central Europe)

Peggy Bette, War widows

Peter Haslinger, Saint-Germain, Treaty of

Roberto Mazzo, Occupation during and after the War (Middle East)

Stefan Marinov Minkov, Neuilly sur Seine, Treaty of

Tariq Tell, Lawrence, Thomas Edward

Tariq Tell, Sykes-Picot Agreement

Timothy C Winegard, Dunsterforce

Tuomas Tepora, Finnish Civil War 1918