The Dragon’s Voice

Well, it has been a few months since we had a newsletter, due to us being away and then being very occupied on family matters. However, the Dragon’s Voice is back! In this edition, we have an article on the worst disaster ever in the Irish Sea, the sinking of RMS Leinster and one from Leslie Lord on his Uncle Albert’s unfortunate death. As ever, we owe many thanks to Jim Morris for allowing us to use his WWI day by day material on the Facebook page.

Trevor

The Programme for 2018

Oct 6 : Jeremy Gordon-Smith - Photographing the Fallen, a War Graves Photographer on the Western Front 1915 - 1919

Nov 3 : Trevor Adams: What Happened Next? The Aftermath of WWI

Dec 1 : Christmas Meal

Last month’s speakers

After our summer break, the branch resumed with two speakers, both branch members. Steve Binks updated us on the progress of the pilgrimage to visit and say “thank you” to all British Commonwealth casualties on the Western Front.

Darryl Porrino spoke on unfortunate or unlucky deaths in WWI. This does explain some of the isolated graves in rather unusual locations, eg those resulting from the transport of troops up from Marseille. Darrel’s talk has encouraged Leslie Lord to write about his uncle, and Les’ article is in this edition.

The sinking of the RMS Leinster – a forgotten tragedy

Trevor Adams

The centenary of the sinking of the Leinster is on 10th October 2018. It will be commemorated both in Dun Laoghaire (pronounced “Dun Leery”), from where it sailed, and in Holyhead, its destination. The maritime museums in both towns have been very busy in making preparations. I hope to be at the event in Ireland.

The RMS Leinster was a ferry which not only carried Royal Mail letters and packets but on board the mail was actually sorted. (Of the 22 postal sorters at work on the day, only one survived.) Its sister ships, all Royal Mail Ships (“RMS”), were also named after the four ancient Irish provinces. The crews were drawn from both Ireland and Wales. The passengers comprised a mix of civilian and military. The military were both those living in Ireland and returning from leave, ones being transferred to GB, and visitors who were looking up relatives on their leave from active service, often emigres serving in the dominion armies. On the fateful journey, there were at least 771 passengers on board, but there is no definitive passenger list. The work by Philip Lecane in the Dun Laoghaire museum has created a list of 567 named casualties. For many years, the CWGC maintained that the casualty total was 176, but in fact that number comes from a 1919 HMSO publication and though it was not claimed to include any military casualties at the time, is frankly nonsense.

On the day in question, the Leinster left her berth in Dun Laoghaire, then called Kingstown, at 8.50am. Just after she had passed the Kish lighthouse some 7 miles out, she was hit by one torpedo at 9.50am. The ship was turned in an attempt to return to Dun Laoghaire but at about 9.55am she was hit by a second torpedo in the engine room and went down very quickly. The RMS Ulster had passed the Leinster a few minutes before the Leinster was hit, but the standing orders were that civilian ships were not to attempt to rescue survivors, as they would be a target for the submarine as well. The distress signal was passed by the Ulster to the Royal Navy, as the Leinster’s radio mast had been brought down. The destroyer HMS Liveley arrived after about an hour and a half, followed by the destroyers HMS Seal and HMS Mallard. The Helga, which had been used to suppress the Easter Rising in 1916, put to sea from Dublin and also took part in the rescue, as did tugs. Unfortunately, sea conditions on the day were poor being recorded by the RN ships’ logs as a wind speed of 6 to 7 from the south-west with a “very high sea” so that, although the lifeboats had been lowered, many had been swamped by the time help arrived.

On the day in question, the Leinster left her berth in Dun Laoghaire, then called Kingstown, at 8.50am. Just after she had passed the Kish lighthouse some 7 miles out, she was hit by one torpedo at 9.50am. The ship was turned in an attempt to return to Dun Laoghaire but at about 9.55am she was hit by a second torpedo in the engine room and went down very quickly. The RMS Ulster had passed the Leinster a few minutes before the Leinster was hit, but the standing orders were that civilian ships were not to attempt to rescue survivors, as they would be a target for the submarine as well. The distress signal was passed by the Ulster to the Royal Navy, as the Leinster’s radio mast had been brought down. The destroyer HMS Liveley arrived after about an hour and a half, followed by the destroyers HMS Seal and HMS Mallard. The Helga, which had been used to suppress the Easter Rising in 1916, put to sea from Dublin and also took part in the rescue, as did tugs. Unfortunately, sea conditions on the day were poor being recorded by the RN ships’ logs as a wind speed of 6 to 7 from the south-west with a “very high sea” so that, although the lifeboats had been lowered, many had been swamped by the time help arrived.

On their first landings at Dun Laoghaire, HMS Lively brought in 127 people, HMS Seal 51 survivors with two bodies, and HMS Mallard 20 survivors, with one body. Throughout the day of 10th October, boats continued to arrive at Dun Laoghaire with survivors and, inevitably, more bodies. By 10pm, more than 100 bodies had been recovered. Over the following weeks, bodies were washed up all over the Irish Sea coasts.

Many of the dead were buried in Grangegorman military cemetery in Dublin, which, incidentally, predates the formation of the CWGC. One North Walian there is Ezekiel Thomas of the RWF who was on his way home to Glan Conwy for his father’s funeral. A total of 12 RWF soldiers died on the Leinster, including one washed up at Abergele.

Civilian and military dead are buried far and wide.

- US sailor Perry Tailor is buried in Florida.(Don’t forget there was a considerable US Navy presence in Ireland by 1918*, and the Leinster had been escorted on occasions by US Navy ships, as well as by the Royal Navy.)

- Frank Higgerty, about to take up a commission in the army, is buried in Ottawa, Canada.

- Margaret Johnston is on the Great Orme at Llandudno.She was an English lady who had moved to Wales to avoid air raids in Southern England.

- Six crew are buried at Maeshyfryd in Holyhead, including a stewardess.

- On the Isle of Man, 11 identified bodies were washed up, some of which were repatriated, and a number of unidentifiable ones which were buried in unmarked graves on the island.Six known casualties are buried on the island today.

- A father and son, both called Charles Daft, are buried in Nottingham.

- The bodies of two members of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, Lieutenant Crawford and Pte O’Brien, were washed up in SW Scotland and they are buried in Kirkbean and Portpatrick churchyards.

- Canadian nursing sister Henrietta Mellett is buried in Mount Jerome civilian cemetery in Dublin

In addition to the above,

- Twenty-six crew are on the Merchant Navy Memorial at Tower Hill in London, with addresses both around Holyhead and Dun Laoghaire.

- VAD Anne Barry is on the memorial at Brookwood cemetery in Surrey.There were 5 VADs killed on the Leinster.

- Josephine Carr was the first member of WRNS to be killed in action.She was a clerk from County Cork and is commemorated on the Royal Naval memorial in Plymouth.Her death gives added irony to the quirky motto for the WRNS “Never at sea”!

But what of Robert Ramm and his crew on UB-123? It is likely that the U-boat entered the Irish Sea by going round the north of Scotland, down the west coast of Ireland and up into the Irish Sea from the South. It is believed to have sunk the tanker Eupion 10 miles west of Ireland on 3rd October. After the Leinster sinking, UB-123 went north. On 18th October 1918, UB-125 outbound from Germany received a message from UB-123 asking for advice on a route through the Northern Barrage minefield which had been laid since March 1918 by the British and Americans to block the route for U-boats into the Atlantic from the North Sea. UB-125 responded with some suggestions. UB-123 acknowledged the message, presumably from a location north east of Muckle Flugga in the Orkney Islands. Nothing was ever heard of UB-123 again. She is presumed to have hit one of the mines that day, as both British and US ships reported hearing a mine explode. UB-123 was lost with all 36 crew.

Ironically, eleven days after the sinking of the Leinster, the German naval command issued an order to U-boats that they were only to attack military vessels and in daylight, as the armistice was pending.

So, why has the Leinster sinking been forgotten for so long?

- The Irish War of Independence broke out between Irish nationalists and the British forces within a year of the sinking.It thus suited each side to deliberately forget the part played in WWI by Irish men and women.Irish officialdom wished to construct a myth of perpetual Irish struggle against British imperialism down the centuries, and the Irish serving in the British forces was an awkward fact to deal with.British officialdom sought to downplay the Irish contribution to WWI, not least because of the loss of the Irish republic but also to justify the behaviour of British politicians and forces in Ireland in the 1919-1921 period.Thus, the loss of the Leinster became part of the suppression of WWI memories on all sides.

- Historians have made a mess of the issue and have grossly under-stated the deaths on the Leinster. As said above, this partly stems from a 1919 British publication that did not include military casualties British Vessels and Merchant Ships lost at sea 1914-1918 and, frankly, sloppy research work on the part of historians in subsequent years.

- A lack of information about those who died has also played a part.The tragedy itself has been remembered in Dun Laoghaire and Holyhead to some extent but it is really only with the stories of the victims becoming known that true remembrance is possible. Of course, the work of Philip Lecane and colleagues at the Irish Maritime Museum and those at the Holyhead Maritime Museum has been central to this task.

*By 1918, there were 34 US Navy destroyers based in Dun Laoghaire, and some 104 US Navy ships in SW Ireland, at Cobh and Bantry, including dreadnought battleships.

References

Torpedoed! The RMS Leinster Disaster, Philip Lecane, 2005, Periscope Publishing, Penzance, and talk to the Dublin WFA, June 2018

An underwater 3D image of the Leinster as she now lies is here

A Long Lost Uncle

Leslie Lord

September’s speaker on accidents to soldiers reminded me of my Uncle Albert.

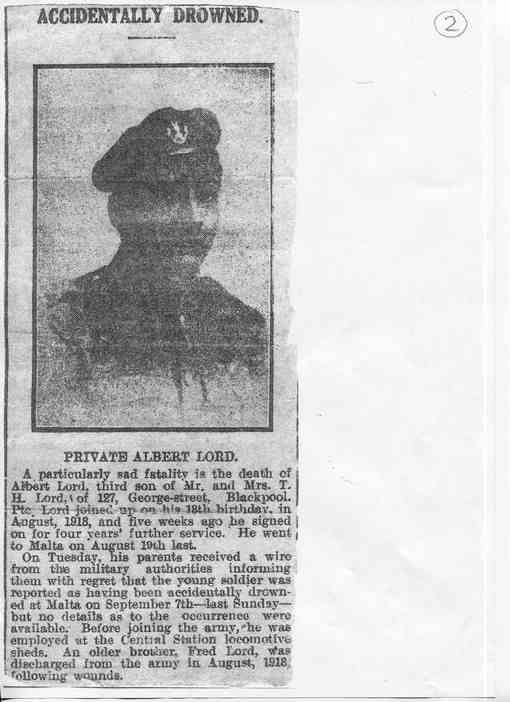

For years all I had was a small newspaper cutting with a photograph and the brief details of his family, military service and that he was accidentally drowned at Malta and mentioned that his older brother had been discharged from the Army in August 1918.

I had never heard my father refer to his brother Albert. Maybe this was an attitude of the times as my parents also never mentioned to me the death of their first born son Albert Edward aged 5 in 1925.

My father died in 1959 and my mother survived until 1980. When her house was cleared all relevant papers were collected by my older sister. With the help of her son and grandchildren she cleared out the loft of her house about six years ago and anything of a military look came to me.

It was like "Christmas"! Amongst the medals, pay books, and medical records there were letters. Two caught my eye immediately, one from Uncle Albert to my father and one from a Captain in the 1st Loyal North Lancashire Regt in Malta.

Uncle Albert's letter looks to have been written on Monday 2nd September (actually Monday was the 1st September 1919) following his arrival at St Andrews Barracks, Malta. It details his journey from Tidworth on the 19th August to Dover, the train from Boulogne to Marseilles and then sailing on the HMSTS Caledonia to Malta.

He notes that the mail leaves on a Tuesday and I am sure that he would have had his letter in the post by Tuesday 2nd September 1919.

It would be reasonable to expect this letter to take at least two weeks from being posted in Malta to arrive at its delivery address in Newcastle on Tyne, so that would make it about 16th September 1919.

The headed paper letter from Captain G.G.R. Williams, dated 14th September 1919,which I think would be addressed to Uncle Albert's father, details the unfortunate circumstances which lead to the death of Private Albert Lord on the 7th September 1919. The mention of being buried in Pieta Cemetery with full military honours took me straight to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records where I found that Uncle Albert was buried in Plot B, Row XX, grave 8.

When you look at the date of Uncle Albert's letter and that of his death, he died long before the letter to his brother would have arrived.

My grandparents would have been upset when their son Frederick returned home from the Army in August 1918 with the loss of an arm only to learn that in the same month their 18 year old son Albert had joined the Army. They would have had some comfort that by the time he had completed his basic training the major elements of the war would be over. His decision in 1919 to sign on for a further four years may have given him a broader outlook on life then returning to the locomotive sheds in Blackpool where he had previously worked.

For over 90 years, these letters had been stored and transported between at least five houses before I had to opportunity to see them. There are still papers referring to family members during WW1 & WW2 which are yet to be investigated!

To visit Uncle Albert's grave is on my long list of things yet to do in life.

On the following pages are a letter from Albert to his brother Fred; a letter from Albert’s company commander; and a newspaper cutting.

Letter from Albert Lord to his brother Fred

Pt A Lord 57645

D Coy 1st L.N.L. Regt

St Andrews Bkd

Malta

Monday, August Sept 2nd

Dear Fred,

Just a few lines to let you know that I have arrived at my destination. I left Tidworth on the 19th August went to Dover from Dover to Boulogne then to Marseilles and stayed there for 3 days in a Rest Camp and it was not half a hot place for I only went down the town once and that was enough; then to Malta on HMTS Caledonia and was 3 days and 2 nights, but very glad to say I am none the worse for the journey. I slept on deck both nights and it was grand - the sea was like a bath of water, and I could hardly tell I was in a boat.

We were nearly 50hrs in a French train from Boulogne and sometimes I could have walked faster. We were put in sidings for hours at a time 2 or 3 times. Well Fred, what I have seen of Malta I like very much and so far I would sooner soldier aboard than in England, and things are very cheap here: Gold Flake cigarettes 4d for 10, and fruit you can get it given to you nearly, grapes 2.5d/lb and peaches 3d/lb. The barracks are fine, could not wish for better, so you can see I am quite content. Now don't forget and let me have a letter and I will always answer them the mail leaves here every Tuesday. No more news at present.

Your loving brother

Albert

Letter written and posted on Tuesday 2nd September 1919.

He died on Sunday 7th September 1919.

Buried with full military honours on Tuesday 9th September 1919 in Pietra Cemetery, about 4 miles from the barracks.

Albert would have died before his brother Fred received the letter.

Letter from Albert Lord’s company commander

1st Loyal North Lancashire Regt

St Andrews Barracks

Malta

14/9/19

Dear Mrs Lord,

I am writing with greatest regret to tell you of the death of your son. I have already cabled the bad news to you but I know that you will want to hear from me as well.

He went down to bathe on Sunday afternoon and altho' apparently unable to swim he pushed off the rocks straight out into deep water. Every effort seems to have been made to save him but unfortunately with no success. By the time he was finally brought to the surface all hope of bring him round was gone. His loss is deeply felt with the coy and with the battalion. He was very popular amongst officers & men & in every way a splendid soldier. As you probably know he was regimentally employed in the Quartermasters stores as a storeman, a position only given to a good & perfectly reliable soldier.

He was buried on Tuesday 9th with full military honours in Pieta Cemetery about 4 miles from here. His death was a great shock to us all & you have the deepest sympathy of both officers and men in your bereavement.

His personal effects & a registered letter parcel which is unopened but I believe contains a present for his mother bought the morning before his death, I will send to you shortly. There will also be some money coming to you from me apart from any credit he may have with the Regimental Paymaster. I cannot tell you the exact amount yet but it is about £21. £5 of this is a war gratuity which he had drawn and the remainder is from the sale of his military kit amongst his pals in the company. If there is anything else I can let you know please write and ask me. Please believe me when I say how very sorry I am for you in your loss, as during this war I have had a lot of personal experience of what it means to lose those one loves, with deepest sympathy for Mr Lord and yourself.

I remain yours sincerely

G.G.R. Williams, Capt., O.C. D.Coy

The local Blackpool newspaper cutting is below.