The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have articles by Steve and Nancy, on CWGC Efiles, Terry Jackson on the evolution of the German helmet in WWI, and a review by Keith of a book on Wrexham and WWI.

Zoom talk. There were will a Zoom talk at 8pm on Friday 9th October on Gordon Shephard – the man who never was? by Trevor.

The details of how to connect are as follows. You can either click on the link and it will take you through to Zoom and download Zoom software and take you into the meeting, though you will need to enter the passcode when asked. Otherwise, you can download Zoom software and set up your own free account. You then use the meeting ID and then the passcode to enter the meeting. Doors open at 7.45pm! Click on “Join with computer audio” to be able to listen. You can click on “Join with computer video” if you wish to be seen!

Time: Oct 9, 2020 7:45 PM London time

Join Zoom Meeting:

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81096652185?pwd=QlEycW9xbStJSUI2NDJ5bTczV0tGQT09

Meeting ID: 810 9665 2185

Passcode: 605121

Family correspondence files released by CWGC

Steve and Nancy Binks

The CWGC have recently added a new source of research to their growing on-line archives. Known as “Efiles”, they are correspondence files between the commission and next of kin covering subjects such as: exhumations, inscription requests, return of wooden crosses, maintenance and upkeep of graves etc.

The records can be searched by title, such as “exhumation”, casualty name or by burial ground. All the Efiles will open by clicking on the reference number. (Other archive files will open if there is an attached media file). Unless you are looking for a specific casualty, the burial ground search criteria offers the most interesting, as it details all the burials where Efiles exist from the same burial ground.

The files make compulsive reading. As I had already researched Bethune Town Cemetery and its burials (see last month’s Dragon Voice), I thought I would start with “Bethune” as my search criteria. This returned 33 documents, not all Efiles; some are photographs or committee meeting minutes, indeed anything where “Bethune” returns a result.

Scrolling down... the Efiles eventually appear, the first of which is in regard to Bombardier Henry Jeffrey and the Commission’s wish to replace the private memorial on his grave for a “CHS”, ie a Commission headstone, (so I worked out!) Correspondence is mostly in date order and quite easy to follow, using arrows or scroll bar.

Interestingly, the Commission stood firmly behind their principles of equality when dealing with private (or none standard) headstones, but the decision usually lay with the next of kin. Where the memorial was placed by colleagues of a serviceman’s unit, the Commission tended to correspond with the regiment (for example). Usually a request for the cost of upkeep was sufficient for them to accept a CHS!

Readers may remember the case of Captain Arthur Durie’s exhumation by his wife from Loos British Cemetery, covered in a previous edition of Dragon’s Voice? Well, whilst Nancy watched the tedious first “Hobbit” film on television, I decided to read all 430 pages of the Efile! What a tenacious lady the mother was. At one point, the Commission was expecting her to visit her son’s grave and passed on instructions to ensure it was in good order. Letters in her file include Fabian Ware, the Prime Minister of Canada and Rudyard Kipling. Although the French authorities wanted to press for prosecution, the British government (and IWGC) preferred to allow the problem to disappear, afraid of the (bad) publicity.

Another file (Tyne Cot) details the correspondence between the Commission and the Hopkins family (of Canada). It details the families fight to regard their son’s remains as their property, as it was the father who, with the assistance of an exhumation team, had found his son’s remains! He was buried at Tyne Cot, but exhumed by the family. However, they were apprehended at Antwerp and the body was later reburied in the military plot at Schoonselhof Cemetery.

Always anxious to learn more about the burial and commemoration process, I came across the file of the Slipp family, (Lillers Communal Cemetery). It tells the heartfelt story of Mrs. Slipp who cannot afford to pay for the inscription on her son’s headstone (Private James Slipp) and requests a photograph. Rather coldly – in my opinion – the Commission respond by informing Mrs. Slipp that their funds no longer cover photos and advises her to contact other agencies. Later correspondence includes her request for information about a visit to her son’s grave, with the mistaken impression that the Commission organises trips. A quick check on Private Slipp’s burial record shows there is no inscription.

This got me thinking. I believed that when the Commission was faced with families not being able to afford the cost of inscriptions (21/2 d per letter), they waived the cost by accepting a voluntary payment up to one pound. (This is according to Philip Longworth’s book on the history of the CWGC, “The Unending Vigil”. I have felt disquiet with this book for some time, having read it three times!). He was the Commission’s historian.

If you don’t have time to read the whole file, the Commission have included a brief synopsis of the file contents on the search page. Interestingly, they seem to have overlooked the main reason for Mrs. Slipp’s first letter! (Who said ALL ranks were treated the same?)

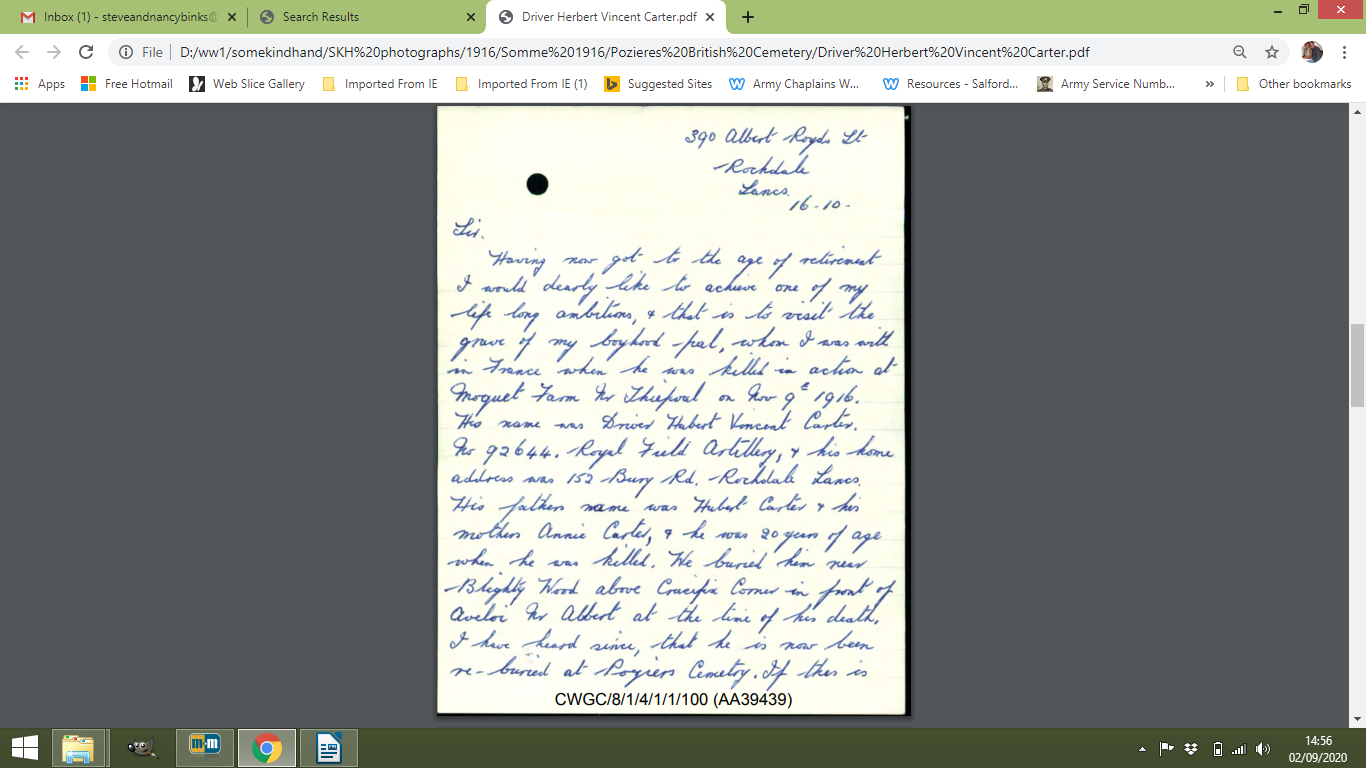

Here is an example, below, of a letter from the Efiles.

Mr. G. Warden, a lifelong friend of Driver Herbert Carter, writes to the Commission ahead of his own pilgrimage. Letter dated 1961.

The German Steel Helmet

Terry Jackson

In 1914, the German Army went to war with the traditional spiked helmet made of leather. As with the other belligerents, the rapid increase in artillery firepower meant that something more resistant to shrapnel and flying debris was needed.

The first attempt to give some protection was by the Army Group Gaede* in early 1915. (*The unit’s commander). They were active in the Vosges. It is a very rocky area and many of the trenches were in rock cuttings. This led to a high level of splintering from shell explosions with the inevitable effect of wounding, especially to the head.

With no immediate developments at the national level, the group decided to design one themselves. Lt-Colonel Hesse the Chief of Staff headed the project. This was a specialised skull cap somewhat more developed than the French calotte and included a nose-guard. It was quite heavy and a small cloth and leather cap was worn underneath for comfort. The steel was 5-7mm thick and  weighed 2.05kg. Most were subsequently melted down and are rare nowadays. (Photo above: Gaede helmet).

weighed 2.05kg. Most were subsequently melted down and are rare nowadays. (Photo above: Gaede helmet).

At a more national level, in 1915 Professor Friedrich Schwerd of Hannover Technical Institute and also a Captain in the Landwehr, was in contact with Professor August Bier, the Naval Doctor-General and an army consultant. Schwerd had set up an electromagnet with which he intended to extract splinters from the brains of injured soldiers. During their conversation Schwerd assured Bier that a helmet could be produced to protect against splinters and shrapnel, but not bullets. A study of 100 head wounds showed only 20% were from bullets, the remainder being from shell fragments or shrapnel. A very small splinter could cause massive brain damage and most head wounds were sufficiently severe to take the soldier out of army service. Bier sent this information to 2nd Army. Both experts were of the opinion that a protective helmet could and should be developed.

Copies were sent to the various Army doctors and von Falkenhayn then Chief of General Staff. He in turn advised the Prussian War Ministry that this should be acted upon. After high level discussions in August the War Ministry informed Krupp Essen that the Juncker Foundry in Berlin would develop the helmet and Krupp were to provide the steel. (Junker had already been experimenting with steel helmet designs). By September 1915 after taking expert advice Schwerd (photo left) reported to the Clothing Section of the War Ministry that a helmet should be produced.

The helmet was to be of 0.5mm thick steel with neck and forehead protection. 5% nickel steel was preferred, but 11% manganese steel could be used. It would be able to protect against shrapnel and small splinters but not bullets. Two side vent lugs would allow ventilation. Anti-rusting paint and a top coat would be applied. Consideration was then given to design based on the statistics - 80% of head wounds were from artillery fragments/shrapnel and only 20% from rifle fire.

By September 1915 Schwerd had determined what rationale was required for the production of a helmet and had discussed the matter with several specialist companies. It would be designed to give protection against shrapnel and splinters. Protection against rifle bullet penetration was not feasible as the weight of the extra protection would make the helmet too heavy to be worn. Splinter fragments would threaten from any angle. The helmet also had to allow for soldiers firing whilst lying down. Thus the characteristic shape of a bowl with a peak, a dip by the ears and neck protection produced its recognisable shape, which was similar to knight’s helmets of the past. The helmet would have two proud lug holes to the sides for ventilation and a liner with three pads and a chin strap attached to the internal part of the lugs. After much discussion a separate metal forehead shield was developed which could be strapped from the side lugs. In theory this would assist snipers as they would be firing from a fixed spot and muzzle flash might reveal their position. It proved to be unpopular and was not extensively used. (Photo below: “square dip” helmet).

Various factories were employed in the trials and manufacture of the helmet and liner, reflecting Germany’s abundance of specialist engineering and military equipment companies.

Eventually after many reviews, it was aimed to produce a one piece helmet of 5% nickel steel or 11% manganese steel. After considerable testing, the first shipment of helmets for field study was sent to Captain Rohr’s 1st Assault Battalion in December 1915. These proved satisfactory and by February 1916 they were being used at Verdun. Following good field results, von Falkenhayn authorised a general issue in the same month. The Allies soon became aware of this development and the Parisian newspaper ‘Le Temps’ carried an article on the helmet on 10 March 1916. Gradually more units were issued with the helmet. Austria purchased 416,000 in late 1916 and began producing its own model in May 1917 and manufactured 534,000 themselves. Minor adjustments such as the toning down of light reflection and liner improvements were made over time. (Photo below: Willy Rohr).

In September 1916, through its Military Attaché in Washington DC the Americans attempted to purchase a specimen, but the Prussian War Ministry were unable to oblige. However, one was eventually given to the Americans via Paris. (Photo below: helmet with visor).

Turkey also ordered helmets from Germany in 1918. The front visor was removed and the sides trimmed. It was suggested that was to enable the soldier to touch his head on the ground during prayer, but it was to give better ventilation. Only 5400 were delivered.

In 1918 a variation was introduced with cut outs at the side. This has often been identified for use by wireless operators to accommodate headsets. However, it was to give better ventilation and only limited numbers were issued. As Germany struggled towards the end of the war, recycling of used or damaged helmets was common due to the shortage of material caused by the Allied blockade. It has been estimated that about a million helmets were produced during the First World War. (Photo below: the cutout helmet).

After the War various organisations wore the helmet during the internal struggles in Germany. Prior to the Second World War the helmet was redesigned. It retained the traditional shape but with a shallower bowl of thicker metal. The external lugs were removed, the side air vent being flush. Various internal organisations (fire and police, etc) had adapted designs. German paratroopers were issued with a brimless helmet. (Photo left: visorless helmet)

Towards the end of the Second World War a new design was being tested. Although similar to the original it had no turned curves which were a structural stress weakness. It was the helmet adopted by the East German Authorities until re-unification. Like most other nations Germany is now using a composite material helmet.

(For further information see ‘The History of the German Steel Helmet 1916-1945 by Ludwig Baer-ISBN 0-912138-31-9. Several other books are available that cover helmets and body protection).

East German army helmet

Book Review

Keith Walker

Wrexham

In Memoriam

1914 - 1918

by

The Friends of Wrexham Museum

edited by W. Alister Williams

Published by Bridge Books 2020

493 pages (A 4) format (paperback)

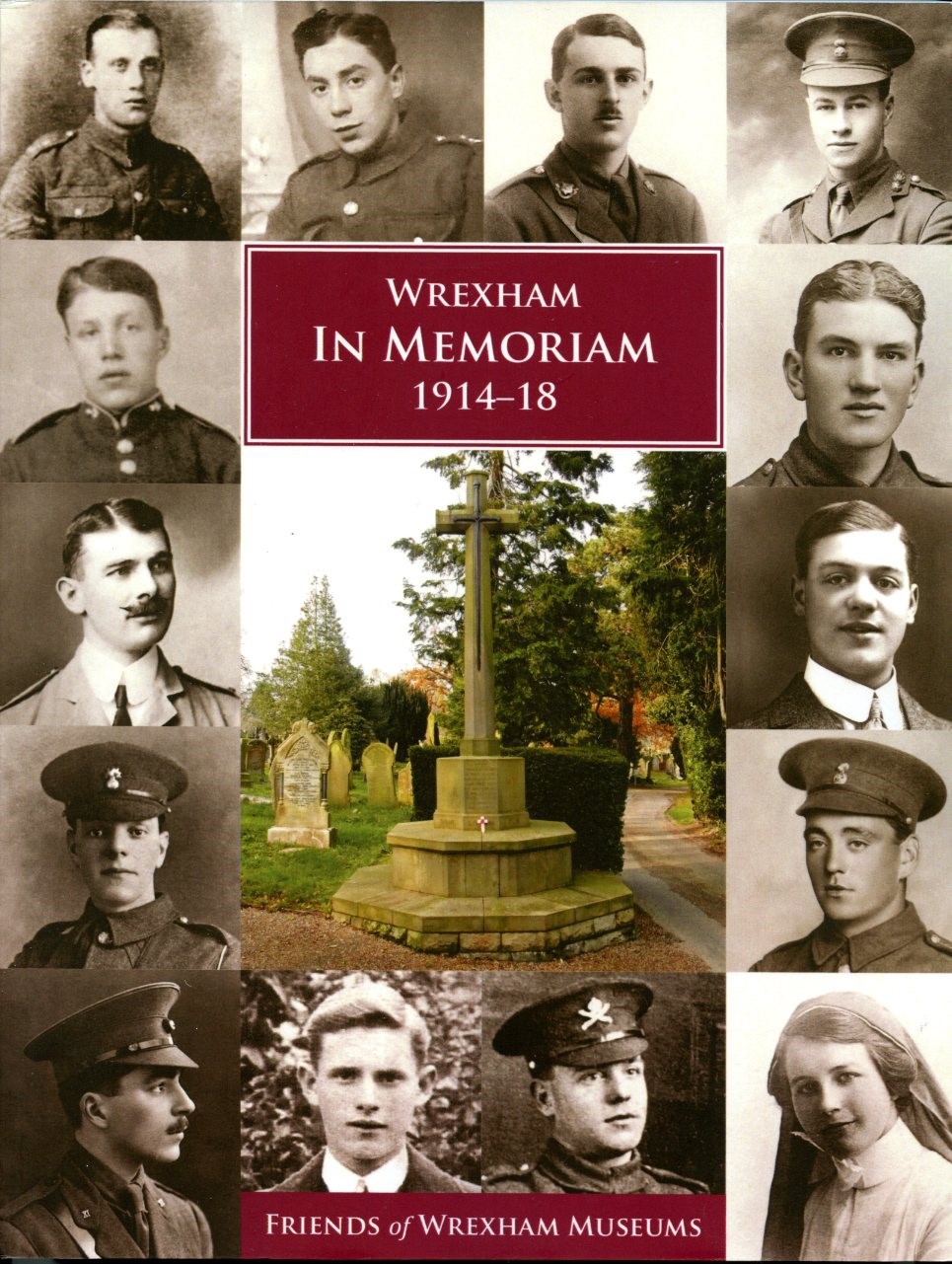

This book has taken over six years to produce. It is a remarkable achievement by Mr WA Williams and his team at Friends of Wrexham Museum. The book contains over five hundred names of men and women who died from the consequences of World War One.

To date, only one hundred copies have been distributed. I know some have been placed in reference libraries and archives. The book is a reference work, comprising of seven chapters:

Contents by chapter

- Preface

- Glossary of Terms

- Wrexham 1914

- War Memorials

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission

- In Memoriam

- Wrexham the War Losses 1914 - 1918

1.Preface

The preface explains how the project was started and defines the area of the town of Wrexham that was going to be researched.

2.Glossary of Terms

The title is self-explanatory, but also defines some of the schemes that were happening at the time, eg the Darby Scheme.

3.Wrexham 1914

A short history of what was happening in Wrexham in 1914. Wrexham at that time was a garrison town. The Royal Welsh Fusiliers were stationed in the barracks. Wrexham was a recruiting centre for the military forces. Three medical units were set up for the injured and recuperating soldiers. On the home front, a munition factory was sited near the railway station.

4.War Memorials

Illustrations of the many war memorials found in churches, chapels, company offices, and schools in Wrexham. In the archives a number of rolls of honour were found. Two notable buildings in Wrexham are the old War Memorial Hospital, now part of Coleg Cambria, and the Memorial Hall, both have a number of memorials in and around them.

5.Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

This chapter gives a brief history and explanation of the work of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. There are also illustrations of some of the memorials to the missing found in France, Belgium, Iraq, Gallipoli, Egypt, Israel, Greece and India.

6.In Memoriam

This is the main part of the book. It contains the names of just over five hundred men and women who met the criteria for the book. It gives a biography of them from before the war, their war record, and the place and date of death, and the location of burial or commemoration. The book also gives details of the casualty’s family post war.

7.Wrexham: the War Losses 1914 - 1918

This is a statistical analysis from the book of the war losses by year, regiment, area, street, background, trade and education.

The book has a number of photographs of the men and women. It is well illustrated with battlefield maps, weapons, memorials and headstones. It is well written and researched. The only criticism I have is that it is in paperback. I would love a hard back copy, but that would have probably doubled the price of the book.

For anyone doing military/family history of the town of Wrexham the book is highly recommended.