The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have an article on the Dutch in WWI, by courtesy of Terry Jackson who is the ex-chair of the Lancashire and Cheshire branch, which meets in Stockport. We also have an article by Keith on books that have influenced him, and a short account of two little books, as he terms them. Trevor

The Netherlands and World War One

Terry Jackson

The Netherlands had every reason to advance peace and peaceful resolution on account of overseas trade and its colonies. It had chosen to remain neutral in conflicts for decades. Two Peace Conferences (1899 & 1907) had taken place in the Hague, so it seemed logical to provide a home for the Permanent Court of Arbitration there. The Permanent Court of Arbitration is an international court of justice that encourages the resolution of disputes which involve states, and was set in the Peace Palace in the Hague. The institution harmonizes with the Dutch efforts for peace.

But in the early years of the 20th century, tensions in Europe were rising. There had been unrest in the Balkans for many years. The Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires were confronted with nationalist movements struggling for independent states or territorial expansion. In a few cases these movements were supported by Russia, and sometimes they were fighting one another. Two antagonistic power blocks were formed. An arms race developed and within a year of the official opening of the Peace Palace the major powers were at war.

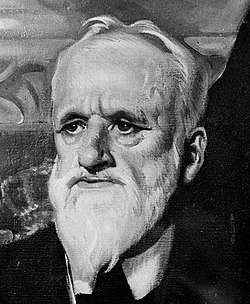

“All we wish is to be left alone”, the Dutch newspaper NRC (Nieu Rotterdamsche Courant) wrote on 1st August 1914. Holland’s position was clear; the country wished to remain neutral. Neutrality was endangered by the Germans, who had originally planned to pass through the province of Limburg to invade Belgium and France. After a few days of war, the Germans and the British indicated that they would respect the neutrality of the Netherlands, but only if this neutrality did not benefit the enemy. Therefore the Dutch constantly needed to compromise during the war so as not to offend one or both parties. Sometimes it was a close call. In March 1916, for example, there were rumours that the British were planning to invade the country and in 1918 the Germans demanded free transport across Limburg for their war effort. (Photo above left: Pieter Kort van der Linden, PM for most of WWI).

“All we wish is to be left alone”, the Dutch newspaper NRC (Nieu Rotterdamsche Courant) wrote on 1st August 1914. Holland’s position was clear; the country wished to remain neutral. Neutrality was endangered by the Germans, who had originally planned to pass through the province of Limburg to invade Belgium and France. After a few days of war, the Germans and the British indicated that they would respect the neutrality of the Netherlands, but only if this neutrality did not benefit the enemy. Therefore the Dutch constantly needed to compromise during the war so as not to offend one or both parties. Sometimes it was a close call. In March 1916, for example, there were rumours that the British were planning to invade the country and in 1918 the Germans demanded free transport across Limburg for their war effort. (Photo above left: Pieter Kort van der Linden, PM for most of WWI).

In order to prevent an invasion, the Dutch mobilised their army on the 1st August 1914. Approximately 200,000 men joined their barracks and were transported to the borders and the most important fortresses like the Waterlinie and the Defence Line of Amsterdam. The Netherlands made it clear that they clung to their neutrality and were prepared to defend it.

During the war years, the soldiers of the Dutch Army guarded the borders and the camps that held interned soldiers and civilian refugees. They tried to stop smuggling and detected and arrested spies. The Dutch Navy was in charge of the defence of the Dutch East Indies, coastal patrol and minesweeping. For lack of real acts of military aggression, the troops were soon bored, despite the continuing threat of war. Boredom was relieved by sports and educational programs. In the course of the war, soldiers got permission to visit their wives and families more and some returned to shops and farms.

After war began in August 1914 the Germans invaded Luxembourg and Belgium. They burnt and looted the town of Leuven and conquered Antwerp on 10 October 1914. One million Belgians fled to the Netherlands, which had a population of only six million people. Local committees and private individuals spontaneously offered accommodation and help.

A large number of refugees stayed during the war. Eighty thousand Belgians, both civilians and soldiers, eventually spent the four war years in the Netherlands. A lot of the civilian refugees were accommodated in ‘places of refuge’, which were small camps with facilities such as a post office, an infirmary, churches, shops and even libraries. Soldiers were disarmed and interned in camps. There were special camps for British and German soldiers. (Photo left: Dutch soldiers of the era).

A large number of refugees stayed during the war. Eighty thousand Belgians, both civilians and soldiers, eventually spent the four war years in the Netherlands. A lot of the civilian refugees were accommodated in ‘places of refuge’, which were small camps with facilities such as a post office, an infirmary, churches, shops and even libraries. Soldiers were disarmed and interned in camps. There were special camps for British and German soldiers. (Photo left: Dutch soldiers of the era).

The first days of war produced widespread shock in the Netherlands. The Amsterdam stock exchange immediately closed after the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war on Serbia. A large number of people withdrew their savings and pubs only accepted silver coins which were stable in value. Money exchange was in deadlock. The Dutch National Bank took a number of measures to stabilise the economy: they forbade the exportation of gold and introduced emergency money to replace the hoarded silver coins, the ‘zilverbons’. Private individuals took steps on their own initiative. Queen Wilhelmina (1880-1962) made a personal contribution and donated money, wool and garments to a newly founded National Fund for the relief of destitute families.

The Queen was sympathetic to the Allied cause, whereas her husband, Prince Henry of Mecklenburg Schwerin supported the German cause. They had one daughter, Juliana, but he also fathered several illegitimate children. The Liberal Prime Minister Pieter Cort van der Linden kept the country neutral, even though he supported the Central Powers, and held office until the elections of 1918.

The private ‘Netherlands Overseas Trust’, founded on 24 November 1914 by businessmen, bankers and ship owners, was particularly conducive to the stability of the country by entering into an agreement with the British, who were trying to ‘blockade the enemy to his knees’. Dutch importers agreed to have their ships inspected and guaranteed that the shipments were intended exclusively for the Dutch market. The system worked reasonably well during the first two years of the war. The majority of the Dutch population were affected when foodstuff got more expensive. Sometimes they were compelled to settle for brown bread instead of the popular white bread.

In Dutch homes, the news on the war was followed attentively. Newspapers reported extensively on the progress and consequences of the Great War. The Dutch government urged the press to observe a certain restraint: too much praise or too much criticism for one of the belligerent parties might have endangered the fragile Dutch neutrality. Not everyone observed the requested reserve. Some newspapers and journalists were proponents of one of the factions and others were easily bribed. (Photo left: the Dutch Royal Family –Queen Wilhemina with her daughter the future Queen Juliana, and consort Prince Henry.)

But acts of war and war crimes did influence the public opinion. Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956), cartoonist for the anti-German newspaper De Telegraaf, was quite explicit about his ideas. The German emperor was portrayed as an ally of Satan, and the newspaper described the Central Powers as ‘a band of heartless scoundrels who caused the war’. The editor-in-chief was arrested in December 1915 and released after seventeen days’ imprisonment.

But acts of war and war crimes did influence the public opinion. Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956), cartoonist for the anti-German newspaper De Telegraaf, was quite explicit about his ideas. The German emperor was portrayed as an ally of Satan, and the newspaper described the Central Powers as ‘a band of heartless scoundrels who caused the war’. The editor-in-chief was arrested in December 1915 and released after seventeen days’ imprisonment.

Photographs and movies often said more than words. In illustrated magazines like De Prins, De Katholieke Illustratie, Panorama and Het Leven, a lot of space was reserved for illustrated reports. In cinemas, the Dutch watched films and newsreels from England, France and Germany. These were often partial, while the Dutch press was trying to remain neutral.

The Dutch Empire comprised Suriname, the Netherlands Antilles, the Dutch East Indies, and Indonesia. The war made it clear that the Netherlands relied heavily on other countries to keep in contact with the colonies. For instance, the British controlled postal and telegraph services with the Dutch East Indies and restricted imports and exports. Transport of passengers was getting more and more complicated, chiefly due to German U-boats. The Indies no longer shipped their sugar, rice, oil, cotton, tobacco, tea and pepper to Europe, but tried selling them in their own region instead. Shortages in the Netherlands accrued. In the colonies, there were shortages of machines and medical equipment. In the last year of the war, exports nearly came to a standstill. Famine and rebellion appeared imminent.

The commanding staff of the colonial army feared invasions, and were indecisive whether to train and arm the Javanese, since they might have risen in arms against their masters. Their fear was aggravated by the rise of the first nationalist organisations. The situation was different in the Dutch West Indies, where restricted trade and communications were an incentive to small-scale agriculture.

The political consensus of the Netherlands was that they needed to maintain their neutrality. This brought about a number of measures that are still perceptible today. For instance, a number of issues on private schools and universal suffrage (1917) were solved. The shortages showed the importance of organizing the food supply. Partially in response to the flood of 1916, plans for closing the Zuiderzee finally passed Parliament in 1918. Large areas of the Zuiderzee would be reclaimed for farming after the construction of the world-famous Afsluitdijk dam in 1932 (see photo below).

From 1917 onwards, the war was getting closer to the Netherlands. Increasingly, German U-boats and British minefields were an impediment to the merchant fleet and fishery. Since the Netherlands relied on imports from overseas, there was a shortage of important raw materials and, consequently, a decline in domestic production. There were great shortages and prices were rising. Corn was scarce. Compared to the previous year, potatoes were twice as expensive. Meat was getting rare. Rationing was introduced. During the last months of the war more than fifty products – fuel, onions, wood, metal, soap, garments, amongst others – could only be purchased with ration books.

The shortages called for inventive measures. Soup kitchens had to provide cheap meals. School holidays were prolonged. Homes had gas supplies cut from three to five hours each day. The popular allotments provided vegetables. People used balls of newspapers for heating instead of coal. The government tried to guarantee a basic food supply by introducing products like the ‘uniform sausage’ and the ‘popular biscuit’. The Dutch made the best of it and waited for better days.

The Aflsuitsdijk and, yes, that is sea on both sides

Not everyone obeyed the law. A lot of farmers sold their crops on the black market or to the Germans, who were willing to pay much more. Furthermore, the government was forced to sell potatoes that were much in demand, in order to be able to procure fuel. The hungry population was annoyed and plundered food stocks. When Amsterdam housewives looted a freight load of potatoes, nine people were killed.

In the long term, neutrality turned out to be good for the Dutch economy. Industry and commerce were given free rein on the national and international markets now that there was no foreign competition. Companies were forced to develop innovative activities that would turn out to be lucrative – Philips, for instance, started blowing the glass for its light bulbs. Dutch mining experienced a rapid growth since German coal was only imported in very small quantities. The arms industry was developing and aviation growing. At the end of the war, the war profiteers turned out to have become very rich, especially when compared to the rest of the population which was suffering from the shortages. After hostilities ceased, there were three times as many millionaires than before.

The Prime Minister Pieter Cort van der Linden served from August 1913 until September 1918 as the head of a Liberal cabinet. He was pro-German but was able to maintain neutrality. He introduced universal suffrage in 1917 which enabled the Social Democratic Workers Party and the General League of RC, caucuses to win the 1918 election and he was replaced by Charles Ruijs de Beerenbrouch.

Towards the end of the summer of 1918 it became clear the Allies would win the war. Germany was war-weary and had its own trouble with revolution. That country agreed to an Armistice on 11 November 1918. Peace negotiations started immediately. The war may have been over, but it continued to reverberate. The First World War took away many of the younger generation. Nine million soldiers died and a lot of survivors suffered physical and emotional wounds from which they would never recover.

The map of Europe was redrawn in the Treaty of Versailles – signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Franz Ferdinand – and in other peace treaties at the end of the First World War. The Allies demanded territorial concessions and reparations for all the loss and damage during the war. An international organisation, the League of Nations, now had to deal with settling international disputes through negotiation. It could not prevent another devastating war from breaking out twenty years later. The neutral kingdom of the Netherlands would not be spared this time.

Because of the neutral status of the Netherlands, most Dutch war victims were seamen and fishermen. As a consequence, the First World War was given the same attention in the Netherlands as in the surrounding countries.

Terry Jackson

Editor’s note: if Terry will forgive me for adding my two penny worth, it is important to remember that WWI was little more than 10 years after the Boer Wars, and the Boers are of Dutch descent. I recall seeing a statue of the Boer general Rudolf de Weet in the national park of the Hoge Veluwe. So, there will have been empathy for the Boers and some antagonism toward the British. That later changed drastically because of the British efforts during WWII to support and liberate the Dutch.

Books

Keith Walker

I am looking at the bright side of being locked down and told to shield myself. It has given me time to reflect and do some serious reading. Looking at my bookshelves, I asked myself what books have influenced my thoughts and ideas of the concept of the world wars.

When I started senior school, aged eleven, my English teacher introduced me to the world of books, first the children's classics such as “Black Beauty”, and “Treasure Island”, then on to Shakespeare and the classical poets. At the same time, the class was taken to look at the local war memorial which was situated just outside the school. Little did I think then of how much that memorial would play in my later life. One of the names on the memorial turned out to be a relative: he would have been my uncle. This sparked an interest in me of the world wars. I was also given a RAF peaked cap, complete with a cap badge.

As I grew older, I started to read biographies of the men who fought in the war men like Group Captain Douglas Bader, and Group Captain Sailor Malan. This led me to look at the battles, like the Battle of Britain, Battle of the Atlantic, and the campaigns in North Africa, Italy, and D-Day. As well, I looked at the commanders of the battles Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, Air Chief Marshal Keith Park, Admiral Bertram Ramsay, Admiral of the Fleet Dudley Pound, Field Marshal Harold Alexander, and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. From these books, I began to wonder how the battle fitted into the whole war.

Next, I moved on to the grand strategy and the geopolitics. The Eastern Front and the Battle of the Pacific broadened my outlook on war. So, from one man's story to how he fitted within the battle to how the battle fitted in to the war. In this period of my life, it was mostly World War Two that I was interested in, together with politics and social history. Together with my son Philip, we had visited a number of museums, battlefield sites and RAF airfields. After a battlefield tour with Leger to the beaches of Normandy, we were viewing our photographs when Philip said “we don't know much about the First World War.”

The following year, we book a battlefield tour with Leger: “All Quiet on the Western Front.” The tour was an overview of the Western Front. We visited Ypres, Arras, and the Somme. One evening in the bar of the hotel, we were talking to the guide about any books he would recommend to further our interest in World War One. He recommended anything by Lyn MacDonald as a good introduction but warned us “that the First World War was like an itch that you could not stop scratching”. How true his words were!

My reading of the First World War developed over the next few years. Again, I started from one-man stories. Biographies of “Noel Chavasse, Double VC” by Ann Clayton, first published by Leo Cooper in 1992 and re-published by Pen and Sword in 1997. Another was “Corky's War”, the dairy of an RAMC stretcher-bearer 1915-1919 which was first published by Mutiny Press in 2008. For information on the battlefields, I used the battleground series by Pen and Sword. I looked at the field commanders of the war, for example “General Plumer” by Geoffrey Powell, first published by Leo Cooper 1990 and re-published by Pen and Sword in 2004. Another book, on General Horace Smith-Dorrien, really caught my attention, because of his links to the battlefields of South Africa. On a visit to South Africa, I was shown the house where he stayed and was looked after in his later life (but that is another story).

I am a child of the 1960's and was brought up with the conception of “Lions Led by Donkeys”, and “Oh, What a Lovely War”. Two of the books that changed my thinking were John Terraine's “Douglas Haig, the Educated Soldier” first published in 1963 by Hutchinson and re-published in 2005 by Cassell, and his “The Smoke and the Fire” published by Sidgwich and Jackson in 1980. These books dispelled some of the myths that were current at that time about atrocities, casualties, and generals living thirty miles behind the lines.

When I narrowed my reading down to look at the stories of the men behind the lines, I focused on the medical evacuation of the wounded soldiers and concentrated on the nurses. Two books which were of great interest were, firstly, “Unknown Warriors” by Kate Luard published by the History Press 2014. Kate Luard was a nursing sister in the First World War. This book was compiled from “Diary of a Nursing Sister on the Western Front 1914-1915” and was published anonymously in 1915 and as “Unknown Warrior, the Letters of Kate Luard”, published in 1930.

The other book, “Veiled Warriors”, was about allied nurses of the First World War by Christine E Hallett, first published by Oxford University Press in 2014. To understand the real horrors of war, a must read is the “Regeneration” trilogy by Pat Baker. These are “Regeneration”, first published by Viking Press in 1991, “The Eye in the Door”, first published Viking Press in 1993 and “The Ghost Road”, first published in 1995. These books changed my understanding of the First World War. Two others maybe deserve a mention: “Dreadnought” by Robert K Massie, first published by Random House in 1991 explains the tensions leading up to WWI, and the resultant arms race. The other interesting book is “Peacemaker” by Margaret Macmillan, first published by John Murray in 2001, which explains the consequences of the war.

Like the BEF in 1914, which had a long learning curve to fight and win the war, I also had a long learning curve to try and understand the war and its consequences for future generations. Little did I realise when I was taken to look at the Broughton Memorial Gates aged eleven how many battlefield tours I would do, how many books I would read, and also help in the publishing of books on that memorial and of the memorial in Brymbo.

Two Little Book Reviews

Keith Walker

Last year on a holiday in Anglesey, I visited the Holyhead Maritime Museum to further my research into the “Q” ships. I picked up two small books published by the museum, the first being “Holyhead and the Great War” by RE Roberts. In 1920, he collected cuttings of events during the war on the Red Cross, the sewing guild, and recorded the loss of ships from Holyhead. The book of 116 pages is a facsimile of those cuttings. Interesting to read what ordinary people were doing at the time.

“HMS Tara” by Richard Burnell is the story of the Holyhead passenger ship SS Hibernia which was requisitioned by the Navy, and renamed HMS Tara. The ship was entering the port of Sollum in the Mediterranean when she was torpedoed by a German U-boat. The crew were handed over to the Senussi tribesmen and held in the desert. After 134 days, they were rescued by the 2nd Duke of Westminster who was the commanding officer of the Cheshire Yeomanry Armoured Car Corps. The book has 100 pages and is a little gem of a read.