The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have an article on the Christmas Day raid by the RN on Cuxhaven, and a review of a book on the Eastern Front. As there are no talks in December or January, the next edition of this newsletter will be for February 2020.

The Cuxhaven Raid – Christmas Day 1914

Trevor Adams

My interest in tracking Erskine Childers’ adventures lead me to uncovering the Cuxhaven Raid. Having run German guns into Ireland in July 1914, Childers was called up as a reservist to the RNAS to fight against the Germans in August. His famous novel Riddle of the Sands, published in 1903, dealt with a spying intrigue where the protagonists were sailing around the Friesian Islands. In fact, Childers and his friend Gordon Shephard had sailed in and around this area a lot in the era before WWI and they both knew the area well. So, when the idea of a raid on Cuxhaven was dreamed up, Childers knowledge of this coastal area of North Germany was thought to be vital. He was 44 years old at this time.

If your geography is a bit hazy, Cuxhaven marks the end of the Elbe estuary, which leads down to Hamburg. There was, and is, a fort at Cuxhaven to defend the mouth of the estuary against enemies, though today it is largely behind a high dike and is a museum. (Photo below: Fort Kugelbake at Cuxhaven).

The geography of the area is an important aspect of the events. The coastal area is described in German as Watt, which means mudflats or shallows (hence the name Wadden Sea). The island of Nieuwerk lies 8 kms off Cuxhaven and it is possible to reach it at low tide, on foot or horse-drawn wagon. The shallows extend some distance beyond the island. So, approaching this coastline with large ships is simply not feasible. (Photo below – the vast shallow emptiness of the Cuxhaven coast)

The plan was devised to launch seaplanes from ships some distance off the coast, bomb Cuxhaven, the airship base which was thought to be at Cuxhaven, and maybe the naval base at Wilhelmshaven. The crews would then land the planes on the sea and be recovered by submarines, the planes being abandoned, or by surface ships. The “slight problems” with this plan include the fact that it took place in late December with a short day length, there was sea mist, the planes of the era were very unreliable and could not attain any great height, so were flying at roof top level. The British did not even have a proper hand grenade in 1914, and even if they did have a worthwhile bomb, the planes would not have had the capability of carrying any significant weight. Even later in the war, the choice was between taking an observer/gunner and taking a weapons load of any merit.

The airship base “at Cuxhaven” is the main aspect of this article. Its location is worth clarifying because it is not in Cuxhaven. It was, and is, an airfield at Nordholz, 12kms south west of, and inland from, Cuxhaven. Today, there is a museum on part of the site, with a German Air Force coastal patrol base on the airfield itself. Please note, it is not a “Zeppelin” base, as the museum goes to great lengths to explain that Zeppelins were made in southern Germany and the local manufacturer in the north was Schuette-Lanz. So, it is an “airship” museum. Of course, there were Zeppelins there as well in WWI.

The jewel of the base was the Drehhalle. This was a hangar for two airships which could rotate through 360 degrees. It weighed 4600 tonnes. The benefit was to be able to avoid side winds hitting the airships when they were being removed from the hangar, or returned to it, otherwise considerable damage could be inflicted on the airship by striking the hangar. (Photo below: a model in the museum of the “Drehhalle”)

Many of the German airship raids on the UK started from Nordholz. It was thought, rightly, to be beyond the reach of an attack by ships because of its inland position and because of the extensive shallows on the coast fending off enemy capital ships. So, although attacking the airship base was supposedly one of the aims of the Christmas Day raid, the intelligence on which the raid was based seems pretty shoddy.

The fear of airship raids was far in excess of what they were capable of doing in reality. Gordon Shephard in one of his letters to his father in 1916 refers to the ridiculous panic caused by Zeppelin attacks in England.

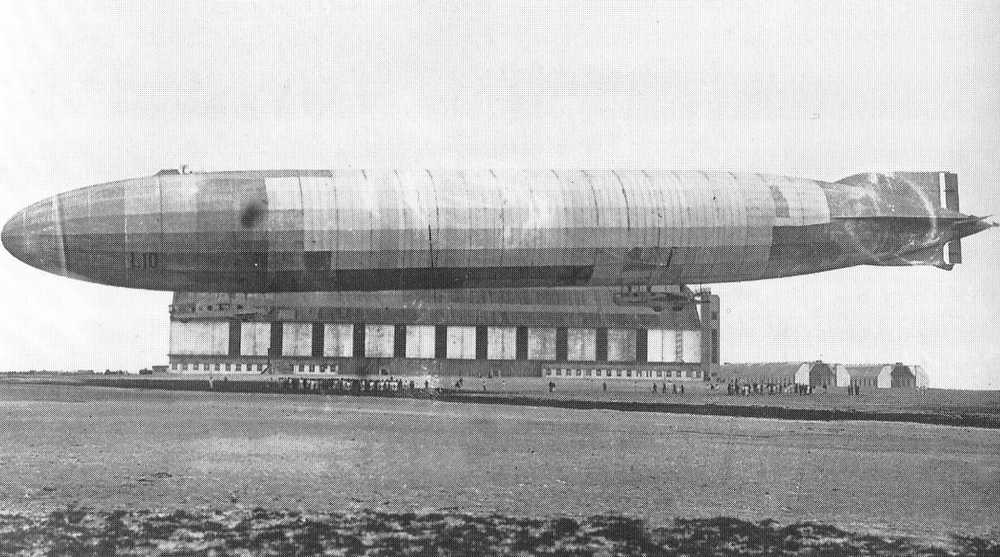

The official British account of the 1914 raid reports that nothing was in fact hit by any of the “bombs”, which is supported by the German account. The British account reports that Flight Sub Lt Vivian Blackburn attacked Wilhelmshaven, encountered heavy anti-aircraft fire and dropped one bomb there. The German book on the history of Nordholz base doubts the accuracy of this. An eye witness who was on duty on that day recalls a low-flying plane being fired at by the extensive flak emplacements on the airfield, dropping a bomb at the gasometer but which landed in woodland, and then disappearing into the mist. Research in the Lower Saxony archives shows that there were no flak emplacements in December 1914 at Wilhelmshaven harbour, and no reports of any bomb being dropped on Christmas Day 1914. So, it looks like the RNAS did in fact attack the airship base at Nordholz by a total fluke and never realised what they had done! (Photo below: airship L10 landing at Nordholz. The tiny dots on the ground are the ground crew. L10 was 163 metres long!)

So, what was the outcome of the raid? The aircrews were picked up by submarines and surface ships, and one crew by a Dutch trawler. The RN surface ships were attacked by German airships, a U-boat and sea planes. In the end, the Germans lost a seaplane, an airship, a trawler and had two planes damaged. The initial belief that the cruiser Von der Tann had been damaged in the raid proved to be false, as she was in refit (which is the reason she was not at the Battle of the Dogger Bank in January 1915). The British lost four seaplanes, and had four destroyers and a submarine damaged. Two dreadnoughts, Monarch and Conqueror collided and required to be repaired in dockyard. Two of the pilots were awarded the DSO and two CPOs (observers) were awarded the DSM.

What is the verdict? Well, it seems to have been an ambitious plan drawn up with sketchy intelligence, and which required much better aircraft than were available in 1914. It was the first combined attack ever by ships and planes but in reality it achieved little.

Erskine Childers continued in RNAS. Ultimately, he was one of the people who negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, but was on the anti-Treaty side in the subsequent civil war. He was betrayed by persons unknown, captured by the Free State army, given a pre-emptory trial for illegal possession of a handgun (in fact, given to him originally by Michael Collins) and was shot in Beggar’s Bush Barracks in Dublin on 24th November 1922. His son, also called Erskine Childers, became the fourth president of Ireland in 1973.

References

Schiffe am Himmel, Nordholz, Geschichte eines Luftschiffhafens. [Ships in the sky, Nordholz, History of an Airship Harbour] Hein Carstens. Bremerhaven 1997

The Cuxhaven raid 25 December 1914, http://warandsecurity.com

Book Review

War, Land on the Eastern Front

Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius

Cambridge University Press 2010

The author is an academic historian of Lithuanian origin who now works in the United States.

The book deals with a neglected aspect of WWI, that is the creation by the German army of a state in the occupied East, known as Ober Ost. This is a contraction of Oberbefehlshaber Ost – supreme commander east. The author deals with both German and Lithuanian sources which often reveal diametrically opposed views of a situation. He has unearthed a lot of previously unknown material.

In essence, it was Ludendorff’s idea to create a puppet state. The aim was to create a model for German colonisation in Europe and elsewhere. As part of this, one of his suggestions was to create a wall from the Baltic to the Black Sea to keep out the “hordes from the east”. Does this sound a little familiar in the current political climate?

The area initially encompassed was modern Lithuania, parts of Latvia, Poland and Belorussia. At the time, these were all part of the Russian empire, so the German soldiers thought that they would be dealing with the “Russians” as a homogenous entity. Of course, we know that there is and was, considerable ethnic diversity in the Baltic region, in fact more so then than now, not least as the Baltic German population no longer exists. By 1918, with the collapse of Russia the eastern border of Ober Ost was extended to a line of Kursk-Pskov-Narva. If you look at a map that is a long, long way east. In 1918, the German army had to keep one million men in the east to deal with this enormous area, including to organise the harvest and transport of food supplies to the starving millions in the countries of the central powers in Europe. Transport is complicated even today by the fact that the Russian railway gauge is different to the rest of Europe, so goods have to be transhipped to other trains at the border, or the train bogies changed.

The aim of Ober Ost was to educate the locals, to make them cleaner, to remove “filth” and in effect to turn the locals into quasi-Germans. There are of course parallels with British colonisation elsewhere. The agent for all this was the German army, in effect being used as an agent for social change. German culture was to be taught in schools and newspapers were produced to help educate the masses. However, all this was done in German, not in the local languages, so success was very limited, eg the locals could not read the newspapers that were supposed to educate them. The teachers did not speak German either.

Those local men who had not been forced into the Russian army at the start of the war were now forced to work for the German army. The German system in Ober Ost was rigid and did not meet the realities of daily life, eg the practicalities of farming. Lithuanian sources indicate that the indigenous population regarded themselves, probably accurately, as being very much trodden on by the German army whilst the view in the German records is somewhat rosier.

Issues facing ordinary German soldiers include that of dealing with the scorched earth retreat of the Russian army and of comprehending that the civilian population was not an homogenous group of “Russians” but an ethnic and religious mixture.

The tale is told of three men, in one town, called Schmidt, Kowalski and Kusnjetzow – all three names meaning “smith”. In spite of having a German name, Mr Schmidt regarded himself as a nationalist Pole, Mr Kowalski as a thorough Russian in spite of his Polish name, and Mr Kusnjetzow as German, in spite of his Russian name. The Pole with the German name, Schmidt, was a Roman Catholic; the Russian with the Polish name was Orthodox; and the German with the Russian name, Mr Kusnjetzow, belonged to the evangelical church.

The ethnic situation was an awkward one for the German soldiers to deal with, as their own “national” identity was only 50 years old. As well as a Polish local population, there were of course Poles in the German army, whom the local Poles regarded as their kin. The Jewish population could be communicated with, however, as they spoke Yiddish which is a derivative of German. In fact, the fortunes of the Jewish population declined markedly after the collapse of Ober Ost, and they were subjected to horrendous pogroms in Poland and the Soviet Union amongst other places.

Ober Ost was lost by defeat on the Western Front, not collapse in the east. Ultimately, the experience in the east in WWI acted as a foundation for the ideas of German expansionism, especially those later put forward by Adolf Hitler. Some of those soldiers who were in Ober Ost saw this as territory which had been lost by defeat in the west, not by them, and which they had rightfully gained in the first place. This was the basis for the radicalisation of many, including those who ended up in the German paramilitary groups, for example the Freicorps, such as Rudolf Hoess who later became commandant of the Auschwitz camp in WWII.

In WWII, the German involvement in western Russia, the Ukraine, Poland and the Baltic was much less benign than was the case in WWI. The suffering of the Jewish populations in WWII is well known but the 16 million civilian Russian dead are often glossed over. Would all that have happened in WWII but for the Ober Ost experience in WWI?

Overall, this is a valuable book. It is not a conventional WWI “which battle happened where” history and is fairly lengthy. Nonetheless, it is a worthwhile addition to our knowledge of an often overlooked area of the WWI global conflict.