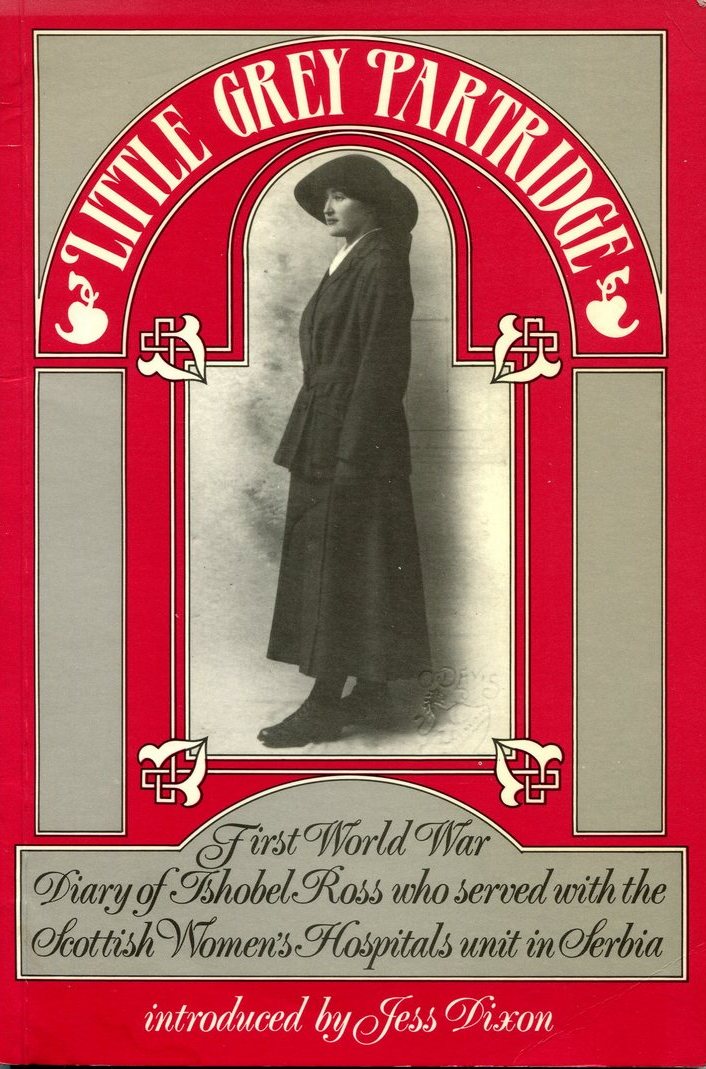

Little Grey Partridge

First World War Diary of Ishobel Ross who served with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals unit in Serbia.

Aberdeen University Press

ISBN 0 08 036419 5

Ishobel Ross was born in 1890 and grew up on the Isle of Skye. She was educated at Edinburgh Ladies College and Atholl Crescent School of Domestic Science and taught cookery at an Edinburgh girls’ school. When the Great War started, she made bandages with the Red Cross in her spare time, but in 1916 she heard about the Scottish Women’s Hospitals at a talk by Dr Elsie Inglis and she decided to volunteer with them. This book is a transcript of her diary from leaving home in July 1916 until her return to Britain in July 1917 and was published by her daughter several years after Ishobel’s death. It includes a fascinating collection of photographs.

I came across a reference to this book when reading about the Scottish Womens’ Hospitals, and I bought it despite a very damning review that appears on the Cambridge University Press website. I am pleased to report that I whole heartedly disagree with that review! It criticises the poor description of surrounding events and lack of deep analysis of her own reactions, but this totally misses the point that this is a personal diary, written for herself. It is a brief contemporaneous record of what Ishobel did and what she wanted to remember. Its value is that it is spontaneous and unselfconscious and as such gives us a picture of day to day life in the hospital and how one young woman coped with it. I totally disagree with the accusation that Ishobel makes it sound as if life in the hospital was ‘equivalent to a Girl Guide camp’. I do not think that a cook at a Girl Guide camp would have reason to record ‘The Bulgars are lying around the hillside unburied, and I am going up to bury some of them tomorrow’, or be required to assist in the operating theatre because of a shortage of nurses!

The war is, in fact, the constant backdrop to all of Ishobel’s writing, the sound of bombardment from the front line, the constant passing of troops of various nationalities, the arrival of the wounded, the funeral parties that passed her kitchen on the way to the hospital cemetery. It is all understated, but she had lived through it and would not forget. She did not need to record the detail. Of particular interest are the number of visitors to her kitchen, officers and men taking any opportunity for a moment of homely comfort and even some POWs managing a few minutes relief from a workparty constructing the road. She also met Serbian royalty and Flora Sandes, the British woman who fought with the Serbian army.

The war is, in fact, the constant backdrop to all of Ishobel’s writing, the sound of bombardment from the front line, the constant passing of troops of various nationalities, the arrival of the wounded, the funeral parties that passed her kitchen on the way to the hospital cemetery. It is all understated, but she had lived through it and would not forget. She did not need to record the detail. Of particular interest are the number of visitors to her kitchen, officers and men taking any opportunity for a moment of homely comfort and even some POWs managing a few minutes relief from a workparty constructing the road. She also met Serbian royalty and Flora Sandes, the British woman who fought with the Serbian army.

Equally understated are the conditions in which she worked, the intense cold, the snow and the mud in the winter, the heat in the summer and at times cooking in the open air because of lack of a kitchen building. One ‘building’ when it was ready was, in fact, only made of rush matting. Ishobel also takes for granted that the staff were expected to speak French and Serbian. After lessons on the journey out, her Serbian rapidly became fluent with constant practice talking to the Serbian orderlies, patients and visiting officers. Later, she was also taught some Russian by one of the patients.

The most detail, however, is given to describing the socialising and fun which the staff of the Scottish Women’s Hospital managed to create. I suspect that this is what offended the Cambridge University Press reviewer! To me, however, this is a vital part of the picture. It gave meaning to a life lived in awful conditions and surrounded by the suffering and often death of their patients. It cemented friendships, not only between the staff but also with the Serbian army and civilians. Any visit to the town for supplies was an opportunity to have coffee with the local Serbian officers, even if you had to push the lorry through the mud on the way back! The mutual affection and respect between the staff of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals and the Serbians is clear. The title of the book comes from the Serbian nickname for these brisk, efficient women in their grey uniforms, ‘little grey partridges’. The final entry in the book is a letter to Ishobel from Captain Mikail Dimitrivitch of the Serbian army, in 1918. It is also evident from current Serbian commemorations of the First World War that these ladies are not forgotten there.

I thoroughly recommend this book to anyone who has ever wondered how the ladies of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals coped and why so many of them remembered their time in Serbia with affection.

Caroline Adams

There is a link to the website commemorating the Scottish Women's Hospitals - Scottish Women's Hospitals