The Dragon’s Voice

Hello and welcome to the first issue of 2017! In this issue, we have articles from both Keith, on Clement Attlee’s WWI service, and Steve, on the burial grounds around Mons. As ever, we owe many thanks to Jim Morris for allowing us to use his WWI day by day material on the Facebook page.

Trevor

The Programme for 2017

Feb 4th : Georgina Holme : Some Great War Commemorations in Anglesey

Mar 4th : John Sneddon : Bombay Sappers and Miners at Neuve Chapelle 1914

Apr 9th : Dr Graham Kemp : How the 10th Cruiser Squadron Won the War

May 6th : Jon Bell : Comparing Medical Services in the Great War with now

Jun 3rd : Stuart Hadaway : RWF and the Battles of Gaza and the Thomas Brothers

July 1st : Colin Walker : Scouts in the Great War

Aug 5th TBC

Sept 2nd : Taff Gillingham : Daddy what did you do in the Khaki Chums; and Development of Uniforms and Equipment.

Oct 7th : John Stanyard : Under Two Flags, the Salvation Army in WW1

Nov 4th : TBC

Dec 2nd : Branch Social

The Burial Grounds of Mons

Steve and Nancy Binks

This is the first of two articles on the cemeteries and churchyards around Mons, particularly in relation to the fighting of August 1914. The articles include some background detail of the casualties of Mons, the medical services and stories - hitherto unknown - of the servicemen and their burials.

Medical Arrangements

Each infantry division had a war establishment of three Field Ambulance (FA); invariably one FA per infantry brigade. However in August 1914, these medical units did not embark or move to the assembly area with their respective infantry divisions. II Corps’ two divisions, heavily engaged on the 23rd August, had only one FA per division; two were still de-training at Havre and two were outside the battle zone, de-training at Valenciennes. Therefore, the 7th FA covered all three brigades of the 3rd Division and the 13th FA covered the three brigades of the 5th Division. At full strength, a field ambulance consisted of 10 officers, 224 other ranks and 10 ambulance wagons.

The 7th FA established their main Dressing Stations in Frameries: a local hospital of 40 beds and two schools of 50 beds each. 13th FA used the “Ecole Communale” at Dour and sent detachments forward to the railway stations at Boussu and Sardon. Further Belgian hospitals were also used at Givry and Paturages. With so little medical support for II Corps and in such a short time frame, it was impossible for both FAs to organise an effective evacuation programme, consisting of advance dressing stations, bearer posts etc. Only twenty of the usual sixty ambulance wagons were available to II Corps. Furthermore the Assistant Director Medical Services (ADMS) was advised to “make local arrangements” for the evacuation of the Corps' casualties. (As per field regulations, this would entail the evacuation of the sick and wounded to the Corps refilling points, where casualties would be transported back to railheads by empty supply wagons). Even with a full complement of ambulance wagons, the roads were too congested and the enemy advance too rapid for this to have worked. Even though I Corps had their full complement - with little requirement placed on them through the day (23rd August) - there was no arrangements made to co-operate.

So, few were evacuated, relying almost solely on ambulance wagons* or local trains. Sixty three sick managed to be sent by passenger train from Dour; a further 42 wounded men were got away from St. Ghislain on a passenger train, the locomotive for which was organised by the stationmaster! Destination for both was Amiens. The vast majority of the sick and wounded were left in the hands of the Belgian Red Cross and at the mercy of their captors.

Together with the hundreds of wounded, five Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) officers (and an unknown number of their staff) were taken prisoner during the Battle of Mons. Lt. Hamilton (C section, 7th FA) notes that about 100 casualties (both British & German) were split between the two chateaux of St Symphorien. For two weeks he was allowed a free hand to travel around the temporary hospitals holding British casualties and to report on those that were well enough to travel as PoW's, or those that required further medical attention. By mid-September, Hamilton was a PoW at Torgau where he states that there were 200 British officers and 800 French.

*An ambulance wagon could hold nine patients

Casualties

A total of 667 servicemen of the BEF were killed in action or shortly died of their wounds in the two days which constitute the Battle of Mons: 23rd - 24th August, 1914. The Official History (OH) details the casualties (killed, wounded, missing and Prisoners of War) as 3,784; the vast majority of these men were taken prisoner, including many hundreds of the sick and wounded.

The greatest fatalities on the opening day of battle were inflicted on Smith Dorrien’s II Corp’s two divisions; 3rd Division’s 8th & 9th Brigades holding the canal around the north and east of Mons felt the full force of von Kluck’s 1X Army Corps (two divisions). Fatalities: 4/Middlesex (90), 4/Royal Fusiliers (41) and the 2/Royal Irish Regiment (38). Further west, defending the canal bank, 14th Brigade, 1/East Surrey’s lost 43 men killed in action. On the 24th August both divisions fought a rear-guard action: 2/South Lancashire (42), 1/Norfolk (53) and 1/Cheshire (55) all suffered high fatalities, once more allowing the BEF to “slip away”.

The Unknown

Of the 667 servicemen killed at Mons, 292 have no known grave and are commemorated on the Memorial to the Missing at La Ferté sous Jouarre. There are 313 “unknown Mons burials” in the burial grounds of August 1914: Frameries (67), St. Symphorien (65) and Hautrage (60), being the most numerous. Many of these burials were carried out by the enemy during their tenure of Mons and perhaps with more diligence a higher number could have been identified.

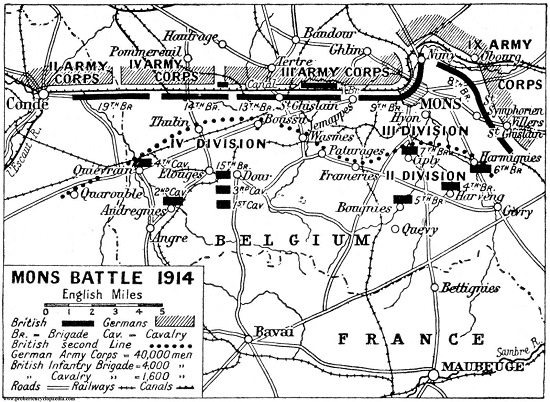

Dispositions of Smith Dorrien’s II Corps on the morning of the 23rd August, 1914.

Dispositions of Smith Dorrien’s II Corps on the morning of the 23rd August, 1914.

Haig’s I Corps, which wasn’t fully engaged, held a refused right flank, through Harmignies, to Binche

The Burial Grounds

The British “visited” Mons on two occasions during the Great War; in August 1914 and again in November 1918. Only one truly British Cemetery was established in Mons (by Canadian 1st & 4th Casualty Clearing Stations); this was later concentrated in to the town communal cemetery extension. All other burial grounds in and around Mons are either communal cemeteries, churchyards, or former German burial grounds.

St Symphorien Military Cemetery remains the most visited cemetery in the Mons sector. Its unusual layout, first VC recipient, and “first and last casualties”, puts it on every battlefield tour of Mons. And it was here that Nancy and I started our Pilgrimage. Its history is well documented.

The cemetery is the final resting place for the vast majority of the officers and men of the 4/Middlesex who fell during the Battle of Mons (86 known burials) and several who died of wounds in the coming weeks. The final three burials of 1914 are of particular interest:

L/14500 Private Michael Tierney

L/14684 Private George Henry Clarke

L/9509 Private Thomas James Spence

These men share the same date of death: 4th November 1914. It doesn't seem conceivable that, of only seven men to die from their wounds, three should die on the same day! Tierney's Medal Index Card states, “Died after capture”. Spence's service record states, “disc in enemy hands” and “reported dead transmitted through the American Embassy and the Foreign Office”. Other than these snippets, there is little to confirm my assumptions that these men had evaded capture and were therefore shot as spies.

The first soldier that we “thanked” was another 4/Middlesex man, L/8659 Private Percy Charles Brandon, who was killed in action on the first day of battle. He was 29 years old and like so many of his battalion, Percy was a reservist. On transfer to the reserve in 1911, he found work as a “carman” for Mr. William Wheatley Waine (furnishings manufacturers), who held a patent for a sofa-bed. Amazing what you can discover amongst service records!

The large communal cemetery in Mons was initially used sparingly by the Germans to bury those men (of both sides) who succumbed to their wounds (from the Mons fighting). By 1917 Mons had become a major centre for PoW’s. (The camp was at Gembloux). The cemetery was extended on its northern side and contains burials of British, Russian, French, Italian, Belgian and Rumanian servicemen.

Hautrage Military Cemetery was also a German burial ground, established in August 1914. In the summer of 1918, the Germans concentrated many British graves from the battlefields; mostly men from the 5th Division: 2nd Duke of Wellington, 1/Royal West Kent’s and 1/East Surrey. With additional post war concentrations, including unknowns, the cemetery is likely to account for all the fatalities for these three battalions sustained at Mons. I wish the detail that we now record regarding the partial known headstones was applicable during these earlier visits!

The remaining burial grounds of August 1914 are communal cemeteries and churchyards, scattered throughout the ground over which the British withdrew, the largest of which are the plots in Frameries (95 burials, 67 unknown), although with the exception of one grave, this is a post war concentration. It was the Canadian 2nd and 3rd Divisions which reached Mons on the 10th November, 1918 and their fatalities lie buried with earliest British burials in Frameries and other communal cemeteries. Amongst the burials are the known and unknown of officers and men from the 1/Lincolnshire Regiment:

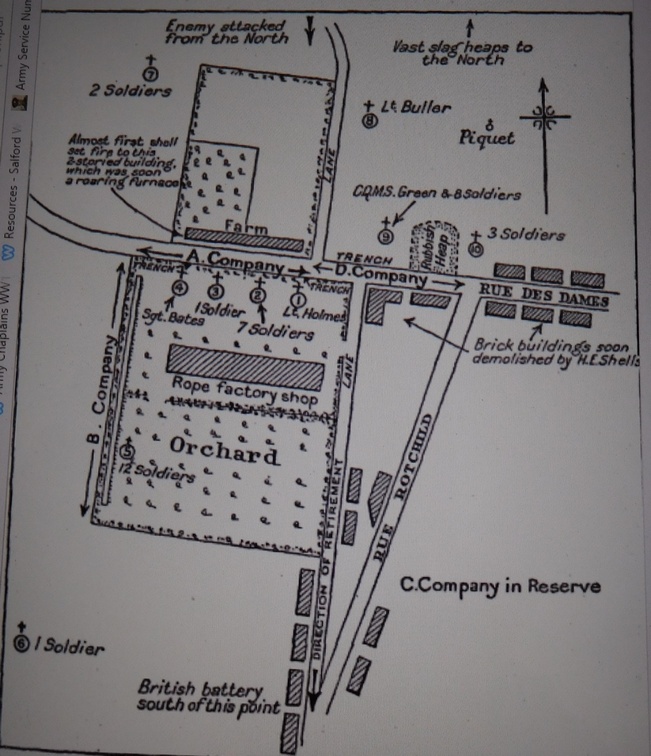

24th August, 1914

The 1/Lincolnshire battalion acted as rear-guard for the 9th Brigade (3rd Division) on the morning of the 24th August. It had arrived at the village of Frameries in darkness the previous evening and at once dug in. At first light (around 4.00am), the enemy opened a fierce bombardment which set fire to some of the buildings being used as part of the Lincoln’s defensive line. The battalions (two) machine guns were well located and together with an excellent field of fire, held by A, B and D coys. accounted for many of the enemy as they tried to advance using stooked straw as cover. As the enemy reformed the Lincoln’s took their chance and “slipped away”, taking the road from Frameries to Eugres.

The Mystery of the 1/Lincolnshire Battalion’s “Unknowns”

Their fatalities were light for such a daring rear-guard action; some twenty two men from the battalion are listed as casualties on the CWGC website. Six have a known burial, five at Frameries and one at Jemappes. Thus, sixteen are commemorated on the Memorial to the Missing at La Ferté sous Jouarre. However twenty nine of the unknown at Frameries Communal Cemetery are badged as “Lincolnshire Regiment”; three of the headstones are over group burials: seven, eight and twelve soldiers and a further two single graves. From further reading and a review of the on-line burial records, it seems that burial information was passed to the Graves registration Unit (GRU) by two officers of the Lincolnshire Regiment who visited the battlefield site at Frameries in December 1918 and identified the place of burial, indicating the location of the known and unknown. It is likely this include at least fourteen men from other units of the same brigade; most likely 1/Northumberland Fusiliers and 1/Royal Scots Fusiliers; both of whom fell back through Frameries.

Whilst looking through the burial reports of both cemeteries, Jemappes and Frameries, I took time to look at some of the old on-line registers. These were originally printed for every burial ground but those for graveyards and communal cemeteries were usually held at the local “Marie” and not at the cemetery, and therefore are rarely scrutinised. Those scanned by the CWGC contain many pencilled amendments, and comments, particularly when graves were concentrated in the later years.

The plan which appears in the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire’s History of the rear-guard action at Frameries. The original “sketch” was drawn by either Captain Masters or Stapleton following a visit to the battlefields of Mons in December 1918. It is likely that the original burials were carried out by the enemy as the only graves identified by name were the officers. It is likely that the point marked “No.5”, the grave of twelve soldiers, could not have contained Lincoln’s, although the exhumation team have accepted the Lincolnshire officers’ involvement as accurate!

The plan which appears in the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire’s History of the rear-guard action at Frameries. The original “sketch” was drawn by either Captain Masters or Stapleton following a visit to the battlefields of Mons in December 1918. It is likely that the original burials were carried out by the enemy as the only graves identified by name were the officers. It is likely that the point marked “No.5”, the grave of twelve soldiers, could not have contained Lincoln’s, although the exhumation team have accepted the Lincolnshire officers’ involvement as accurate!

One such entry is that for S/43486 Private Leonard Harry Lockley, 4/Seaforth, who died on the 30th October 1918, having been taken prisoner in the fighting near Cambrai. He had a Special Memorial headstone erected in Jemappes, which usually indicates that his body could not be found (in the confines of the cemetery). His register entry has been crossed through and amended to Langemarck German Cemetery. It is likely that his body was found when German burials were exhumed from Jemappes and moved to the mass grave at Langemarck, his remains not being individually identifiable. His headstone schedule states; “H/S (headstone) removed, now known to be buried at Langemarck German Cemetery”. In 2004, a new plaque was added to the mass grave at Langemarck for Private Lockley and one other British soldier, who no doubt has a similar story.

It is unlikely that this headstone and the corresponding graves will ever give up their mystery. It reads:

“Twelve soldiers of the Great War

Lincolnshire Regiment

23rd August 1914

Known unto God”

World War One Military Service of Clement Richard Attlee

(A Modest Prime Minister, 1945 to 1951)

Keith Walker

There is an infamous quote ascribed to Sir Winston Churchill about Clement Attlee:

There is an infamous quote ascribed to Sir Winston Churchill about Clement Attlee:

“A modest man, but then he had so much to be modest about”.

Clement Attlee was certainly a quiet and modest man. In his autobiography “As it happened” published by William Heineman 1954, his military service in World War One amounts to two pages in a two hundred and twenty seven page book.

Clement Richard Attlee was born on the 3rd January 1883. He was one of eight children born to Henry and Ellen Attlee in Putney, Surrey. He had four brothers and three sisters. His father was a solicitor. He was known by his family and friends as Clem. [Editor’s note: the London solicitors’ firm of Druces and Atlee still existed in the 1990s, and when I dealt with them there was still an Atlee on the partners’ list.]

Clem was educated at Northaw school in Kent, then Haileybury College and at University College Oxford where in 1904 he graduated with a BA second class honours in Modern History. He then trained as a barrister at the Inner Temple and was called to the Bar in 1906.

In 1906, Clem volunteered with his brother Thomas to help in the running of Haileybury House, a charitable club for working-class boys in Stepney in the East end of London. The charity was set up by his former school, Haileybury. Clem soon became its manager. This is where Clem started his political journey; some people say that Clem “went left by going East”. Part of the activities of the boys club was drilling and learning about the army. It was a way of instilling discipline and pride in the boys. So, on the 13th March 1906, Clem took a commission in the Territorial Army and became Second Lieutenant CR Attlee, 1st Cadet Battalion, the Queens Regiment. In the next few years Clem, who was very committed, took his boys through their drill. He organised camps where they could march and learn field craft. Clem was very keen on rifle drill and marksmanship.

By the outbreak of war in August 1914, Clem by the criteria of the day was considered too old for the army at 31. But in September 1914, he was ordered to report to Tidworth camp in Wiltshire. He was promoted to Lieutenant in the 6th South Lancashire Regiment. He was put in command of a company of seven officers and two hundred and fifty men. His men came mostly from the Wigan, Warrington and Liverpool areas of Lancashire. On arrival, Clem found the officers’ mess president was a Major Pine Coffin who Clem said was “an inimitable raconteur” most of whose stories started with “so I said to this feller, I shall shoot you”.

Over the next few months Clem and his men trained in Tidworth, Winchester and Blackdown. On the 8th February, Clem was promoted to captain and put in command of “B” company. In the spring of 1915, the South Lancashire Regiment were expecting to go to the Western Front. They were issued with maps of the areas they were going to, but they were surprised to be issued with lighter tropical kit. They then realised they were going to either Gallipoli or the Middle East. On the 13th June 1915, the regiment was part of the 13th infantry division and set sail from Avonmouth on the SS Ausonia, a 8,153 ton troopship built by Swan Hunter in 1909. It is of interest that this ship was used in the evacuation of Gallipoli in January 1916. The SS Ausonia was torpedoed and sunk by gunfire by U-55 South-West of Ireland on the 30th May 1918 with forty four lives lost. The ship stopped at Malta and then went on to Alexandria in Egypt. From Alexandria they sailed into the Aegean Sea to the island of Lemnos and the port of Mudros. At 6pm on the 1st July 1915, they sailed on two destroyers to Cape Helles on the Gallipoli peninsula. On entering the bay, they transferred across to the SS River Clyde, a 2,000 ton collier which was used as a makeshift pier.

While they were transferring they were under constant artillery and machine gun fire from the Turkish troops on the hillsides overlooking the bay. Once ashore with all their equipment and provisions, they were sent into the trench system which was very close to the Turkish front line. In a letter sent to his mother by a fellow officer of Clem's, a Captain Baxter stated that the trenches were only 30 yards apart and very close to the enemy. The other enemy of the soldiers was the conditions they were in and the weather. In the same letter, Captain Baxter listed his complaints, first the heat “makes it more like hell than anywhere else I know” quoting Kipling; from 10am to 5pm “one is absolutely prostrated”. The second complaint was the millions of flies which hung around their heads. Thirdly the thirst, they were always short of water. Fourth and last was the evening shelling, some of it shrapnel. Clem wrote a poem at this time called “Stand To”

From step and dug-out huddled figures creep

Yawning from dreams of England; bayonets gleam.

And rat-tat-tat machine guns usher in

Another day of heat, and dust, and flies.

It is no wonder that in these conditions men fell ill. At the end of July 1915, Clem collapsed with dysentery. He was stretched from the battlefield and evacuated from Cape Helles. Clem was told his war was over and the doctors ordered him home to England. Clem insisted that he should be allowed to recover in the military hospital in Malta. It was while Clem was recovering in Malta that his regiment took part in one of the major battles of the Gallipoli campaign. The South Lancashire Regiment landed at Suvla Bay to open a second beachhead ready for the attack at Sari Bair. In this attack the regiment casualty list was very high.

By October it was estimated that of the 100,000 troops left on the peninsula, over half being unfit for duty. Discussions were being made to consider evacuating the peninsula.

In November 1915, Clem re-joined the regiment at Suvla Bay. By this time, the conditions had got even worse than before his illness. The winter weather had set in heavy rain and off shore gale force winds whipping up the sea making the re supply of provisions impossible. After some negotiations with the French, the British government in London made the decision to evacuate the troops. It was at this time that Clem played a vital role in the evacuation. He was given command of two hundred and fifty men and six machine guns, and told to hold the last line around the cove at Lala Baba. Over the next few hours under the cover of darkness, hundreds of troops evacuated the beach. At 3.30 am on the 20th December 1915, Clem was told that all the men were clear of the beach. He then took his own men to the last transports on the beach. On the beach, he met the officer in command Lieutenant General Fredrick Stanley Maude KCB, CMG, DSO (24th June 1864 to 18th November 1917). These two men were the last to leave the beach. So by the end of the Gallipoli campaign, it had cost 43,000 dead and 250,000 wounded.

Clem in later life always supported Churchill. He said “Churchill’s idea was a good one, but the military planners had failed the mission”.

One can only imagine how Clem and his men must have felt as they saw the dawn of that December

morning coming up. Maybe a sense of failure, or the relief of being away from those really terrible conditions they were trying to fight in. They landed at Mudros, and after a brief rest were transported to Port Said in Egypt.

The regiment stayed in Port Said throughout the month of January 1916, re-equipping and patrolling the Suez canal. At the beginning of February1916, the regiment was ordered to sail to Mesopotamia. They sailed down the Suez Canal through the Red Sea, and the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea. They arrived at the Shatt-el-Arab which is just south of Basra on the 25th February 1916. The 6th South Lancashires had been sent to Mesopotamia as re-enforcements. After initial success at driving out the Turks, the Turkish army had fought back and surrounded General Charles Townshend and his troops at Kut. Clem's division was to go up the river to relieve the siege. The regiment boarded two paddle boats to take them up the river. They made their way to a camp at Wadi which was fifty miles from Kut. The Division Commander Lt-Gen Fredrick Maude had devised a plan for the relief of Kut.

On the 16th March 1916, they began their march to Kut. Near the Turkish lines where they dug in, they were a mere 100 yards from the front line trench of the Turks. The attack started at 4.45am on the 5th April 1916. Clem took his men over the top. The first line of trenches was taken by the Sixth Kings Own, and the second by the Sixth East Lancashire Regiment. The Sixth South Lancashire Regiment went through to the third line. It was as Clem and his men reached this trench he said that everything went blank. A shell had hit the trench throwing Clem in the air. When Clem's corporal reached him, Clem was drenched in blood. He had a bullet in his left thigh, and a large piece of shrapnel had made a large hole in his right buttock, he also had a large number of cuts and burns from the shrapnel. As the shelling stopped for the second time, he was put on a stretcher and taken off the battlefield. He was taken back through his lines to a field hospital. At the field hospital, it was found that a piece of shrapnel had gone right through his thigh; a bullet had also gone through his other thigh. They found the bullet embedded in his equipment. He also had damage to his knee joints which made walking impossible. The injuries were so serious he was ordered back to England.

While he was at this field hospital, he was informed that the shell that had hit the trench was one of ours, ie “friendly fire”. It is one of the ironies of war that Clem was carrying a red flag as a marker for the artillery. Over the next couple of weeks, repeated attacks were made, but failed to relieve Kut. On the 26th April 1916 General Townshend surrendered to the Turks after 147 days of siege. Thirteen thousand allied soldiers where made PoWs. Kut was eventually retaken by the British and allied troops led by Lieutenant General Fredrick Maude in February1917.

Clem was taken from the field hospital down the river Tigris to Basra and then on a hospital ship to Bombay. He finally arrived back in England on the 6th June 1916. For the rest of 1916, he was recovering from his wounds. With his regiment still in the Middle East, Clem was transferred to the tank corps. He did some training with them in Dorset but when they were sent to France he was disappointed not to go with them. He says he was seen as an Easterner having only fought in the Eastern theatre.

On the 1st March 1917, Clem was promoted to Major in the 5th Battalion South Lancashire Regiment. He trained with them at Walney Island, Barrow-in –Furness, Cumbria. He had two short spells in France, 15th to 29th March 1917 and the 10th to 24th September 1917 as an observer. Clem was desperate to get back to the front. He did not get his wish until May 1918 when he finally went to France, arriving at Givenchy. Clem was with the 55th West Lancashire Division as they went into Artois in pursuit of the retreating Germans. As the division was advancing towards the German lines at Lille, Clem was carried off the battlefield for the third and last time. The details of this are vague but it seems he was hit and blown up as he was making a dash out of his trench towards the Germans. Evacuated back to England, Clem's war was over.

Of the major campaigns of the war Clem had fought in three of them: Gallipoli, Mesopotamia and on the Western Front. He heard the news of the German defeat in hospital in Wandsworth London. Clem was awarded the1914/15 Star, British War Medal and Victory Medal.

In September 2016, a new biography of Clem Attlee came out written by John Bew published by Riverrun. I thought when I bought this book there would be some new information on Clem's war years. There was not. But what was new is the insight of the letters Clem wrote to his family, especially his brothers. His brother Bernard (1873 to 1943) enlisted as a military chaplain in the Royal Naval Division. His brother Laurence (1884 to 1969) was a Lieutenant in the RASC and finally his brother Thomas (1880 to 1960) who was a conscientious objector and a total absolutist who would not do any war work. Thomas spent some time in jail for his beliefs. In November 1918, when Clem was recovering in Wandsworth hospital, his brother was serving time in Wormwood Scrubs a few miles away. Their mother said she “did not know which of them she was most proud of.”

On my bookshelves, I have over one hundred books on Sir Winston Churchill (30th November 1874 to 24th January 1965) and about the same on David Lloyd George (17th January 1863 to 26th March 1945). On Clement Richard Attlee there are just seven. Historians have let this man down.

To some extent we are living in the legacy that Clem left us after his time as Prime Minister (1945 to 1951). On the military side, there is the formation of NATO and Britain as a nuclear power. On the social side, there is the formation of the welfare state and the birth of the NHS.

Clem was a quiet and modest man who just got on with the job. He left us a pun on himself in the form of a Limerick.

Few thought he was even a starter

There were those who thought themselves smarter

But he ended PM

CH and OM

An earl and a knight of the garter.

Biographic details of:-

Major General Sir Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend KCB, DSO

(21st February 1861 to18th May 1924)

He surrendered to the Turks at Kut and spent the rest of the war as a PoW.

Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Stanley Maude KCB, CMG, DSO

(24th June 1864 to 18th November 1917)

He was the last man off Sulva Bay in December 1915. He led the relief of Kut. He retook Kut February 1917 and took Baghdad March 1917. He died of cholera on the 18th November1917. He is buried in Baghdad (North Gate) War Cemetery.

I could only find one reference to a Major Pine-Coffin

Major John Edward Pine-Coffin, DSO The North Lancashire Regiment, DoD 22nd August 1919 .

Reference and Acknowledgements

Mr Attlee by Roy Jenkins, published William Heinemann 1948

As it happened by CR Attlee, published William Heinemann 1954

Attlee by Kenneth Harris, published Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1982

Citizen Clem by John Bew, published Riverrun 2016

www.longlongtrail.co.uk

Endpiece

Many of you will have known Denis Otter of our branch. Well, I gather from his fellow Burnley WWI expert, Andrew McKay, that Denis’ wife had offered Denis’ books to Andrew. Andrew tells me that when he collected them, he had to take his trailer as there more than a thousand books! Andrew also has a CD which Denis’ son put together of various bits of information which Denis had uncovered. So, in short Denis’ material is in good hands!

www.nwwfa.org.uk