The Dragon's Voice

In this edition, we have an editorial on the some health lessons of WWI, and articles on the Last Emperor, and on WWI traces on the island of Madeira. There is a review of a book on the fall of the Ottomans. Trevor

Editorial

Lessons from WWI

With the current crisis over Covid-19, it was interesting to reflect on lessons from WWI on disease control and treatment. Two aspects came to mind – confining ships passengers to their ships, and the nursing of ill patients.

Do not forget that WWI was an era before the discovery of anti-biotics, which really did not happen until WWII. Vaccination against viruses was known, as Louis Pasteur and Edward Jenner had used it against rabies and smallpox, respectively, a hundred years or so previously,

Looking first at WWI shipping, the Americans in 1917 and 1918 were rapidly building an army from very small beginnings. The soldiers were crammed into over-stretched accommodation in mainland USA, and then shipped to Europe in cramped ships. The imperative was to get soldiers to Europe to fight in the war. The basics of epidemic prevention and containment were ignored. In mid-1918, the Spanish flu hit. It is believed to have been a combination of a Kansas bird flu virus which came from the USA with the soldiers, and an Austrian severe flu virus that occurred in 1916, which resulted in a super virus.

As a result, the Americans lost half of their WWI fatalities to disease. You may see in books dealing with the Americans in WWI that viruses were unknown at this time. This is nonsense. The term was used before WWI. Earlier, in the 19th century, Louis Pasteur had described infectious agents which remained after he had filtered out the bacteria (as viruses are tiny). Also, the basics of public health and disease prevention were well-known. This brings us to the current era when we have seen cruise ship passengers kept cooped up in their ship, which not surprisingly resulted in the rapid spread of the virus through their ranks. The lessons of the transportation of the American troops in WWI were ignored in the modern, panicky response.

The other side of the coin is the treatment for a disease where drugs are of little use (as there are few anti-viral drugs available, even today). In the Spanish flu epidemic and the post-WWI treatment of tuberculosis victims, the management of patients was to have them exposed to fresh air and sunshine. In North Wales, there was a modern tuberculosis sanatorium established in 1918 at Llangwyfan near Denbigh, using these principles. (It still exists, but as a centre for learning disability patients). With the appearance of Covid-19, some infectious diseases specialists are again reminding us of the antiseptic properties of fresh air and sunshine. The inference is that society has become reliant on drugs, typically the anti-biotics available for bacterial diseases, and the basics of this nursing approach have been forgotten. So, another lesson from WWI for the modern world!

The Last Emperor

Or only a saint can fix your varicose veins?

On a recent visit to Madeira, we went looking for WWI history, as one does.

If your geography is not up to it, Madeira is a Portuguese island which lies several hundred kilometres off the Portugal mainland, and the West African coast, in the Atlantic. This location means that it has been an important staging post for ships. Both Captain Cook and Charles Darwin stopped off on their journeys, as did Napoleon, but less voluntarily. Today, most of the ships which visit Madeira are cruise ships that are there for a day or two. There are also longstanding British links to the island, as indicated by the existence of the “English church”, built in 1822, Reid’s Hotel, and Blandy’s wine merchants.

The church at Monte where Emperor Karl is interred

Madeira is the resting place for the last Austro-Hungarian casualty of WWI, Kaiser (“Emperor”) Karl. But how on earth did he get there? He succeeded to the Austro-Hungarian throne in 1916 on the death of Kaiser Franz Joseph. By this stage of the war, the conduct of the Central Powers campaign was firmly in the hands of the German High Command. However, Karl tried to promote peace settlements during the war, without any success. After the end of the war, Austro-Hungary fell apart, with both internal and external armed disputes. The Hapsburgs lost the Austrian and Hungarian thrones but Karl tried on two occasions in 1921 to install himself as Hungarian king. Eventually, the British exiled him to Madeira where he would be out of the way and could not cause political trouble for the Allies, who were busily dividing up Hungary and Austria. Do not forget that Hungary lost more land in the post-war “settlements” than did any other of the Central Powers (excluding the Ottomans’ loss of their Middle East empire).

Emperor Karl - the Blessed Charles of Austria

Emperor Karl - the Blessed Charles of Austria

Unfortunately, Kaiser Karl’s tenure on Madeira, in this life anyway, was not to last long. He and his wife arrived in November 1921, aboard HMS Cardiff. He caught a cold in March 1922 and died of pneumonia on 1st April 1922. He was 34 years old. He is buried in the church at Monte, the area of the Madeiran capital Funchal which overlooks the rest of the city. The side chapel where his coffin lies has the flags of his empire. The wrought iron door is adorned with numerous ribbons in Hungarian national colours (red, white and green) with messages in Hungarian. There have been moves over the years to have him moved to the Imperial crypt in Vienna, which have come to nothing.

Karl's coffin in the side chapel

Karl's coffin in the side chapel

His history does not stop there. In 2004, he was beatified by the Catholic Church. To be made a saint, you need to have performed a miracle, and the one which was deemed relevant for Karl was that he supposedly cured somebody’s varicose veins! In truth, his main good points were his religious piety and his attempts to promote a peace settlement during the later phases of the war. When you think of all the heroic deeds which people did during the war, and often died doing, perhaps a more heroic saint could have been found. This, of course, does not detract from his place in history.

There is a memorial in Vienna to the Austro-Hungarian WWI war casualties. The first name is that of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and the last is Emperor Karl.

The statue outside the church - "Beato Carlos do Hapsburg"

Traces of WWI on Madeira

The links which Madeira has with WWI are not immense but they served as part of the scenario after Portugal went into WWI in March 1916.

Funchal was attacked by a U-38 in December 1916, and three ships in the harbour were sunk. In December 1917, Funchal was shelled by U-156 and U-157 resulting in property damage, and three dead and seventeen wounded. There is a peace monument up behind Funchal on the high ground at Monte, built in 1927 and incorporated the anchor chains of two of the sunken ships. There is a memorial to the Portuguese war dead on the seafront in Funchal.

There are three WWI CWGC graves on Madeira, all in the “English” cemetery which belongs to the English church. Incidentally, the current vicar is from Newport in South Wales. They are:

Commander Cecil de la Mare Goldsmith, DOD 21st January 1917 aged 55 years, Royal Naval Reserve. He was the honorary British naval vice-consul and was retired from the P&O Steam Navigation Company. Presumably this is a death from natural causes or accident. His headstone is a civilian one. (Photo below).

Chief Shipwright (retired) Elias Mann, Service number CH/161737, HMS Argonaut, Royal Navy, DOD 22nd June 1915. Long service and good conduct medals. Served in the Boxer rebellion (1900) and the Somaliland Campaign (1902-1904). He has a CWGC headstone in a dark stone which is presumably local to Madeira*. Was he someone who came back from retirement? Presumably his death is from natural causes or accident. (Photo below). *Footnote: the CWGC headstone information for a WWII casualty below shows that the contract was given to a stonemason in Bangor, Gwynedd, so are they made from North Wales slate?

Seaman George Allen, Service Number1435D, HMS Amphitrite, Royal Naval Reserve, DOD 23rd May 1915. Again, presumably his death is from natural causes or accident. His headstone is the same CWGC style as Mann. (Photo below).

Seaman George Allen, Service Number1435D, HMS Amphitrite, Royal Naval Reserve, DOD 23rd May 1915. Again, presumably his death is from natural causes or accident. His headstone is the same CWGC style as Mann. (Photo below).

The church has some memorial plaques inside the building to, firstly:

“2nd Lt Edmund O Krohn, 84th squadron RFC, born Funchal 13th November 1898. Killed in aerial combat over the Forest of St Gobain on 1st March 1918”

Edmund Krohn is buried at Chauny Communal Cemetery, British extension, on the Aisne. He looks to have been moved from a German cemetery, as the paperwork on the CWGC site gives German language wording for the original grave.

Another plaque inside the church is:

“In proud memory of Robert Trail, Major QVO Corps of Guides, killed in action near Cambrai, December 1st 1917.

He has proven his faith in the heritage by more than word of mouth. Married in this church, May 1914, to Mildred, daughter of CJ Cossart of Madeira.”

Robert Trail was in the Indian Army. The Queen Victoria’s Own Corps of Guides (Cavalry) Frontier Force, (Lumsden’s) was a unit based in the North West frontier of India. In fact, it still exists today as a battalion in the Pakistan army. He was attached to the Jodhpur IS Lancers. He died of wounds and is buried at Tincourt New British Cemetery on the Somme.

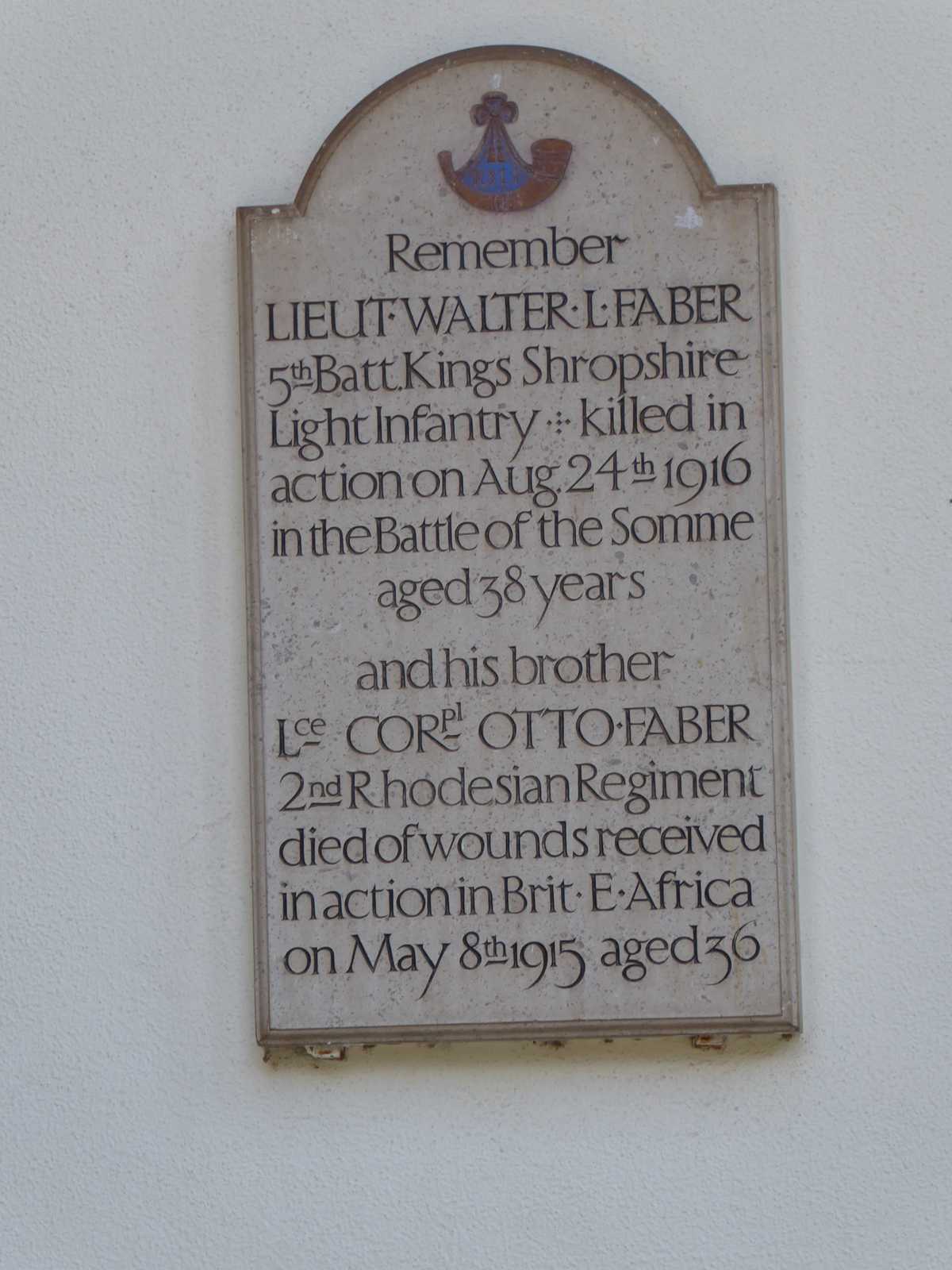

Outside the church is a plaque to two brothers:

“Remember Lt Walter L Faber, Kings Own Shropshire Light Infantry, killed in action 24th August 1916 in the Battle of the Somme, aged 38 years

and his brother

L Cpl Otto Faber, 2nd Rhodesian Regiment, died of wounds, British East Africa on May 8th 1915, aged 36”

Walter Faber is on the Thiepval memorial.

Otto Faber is on the Nairobi British and Indian Memorial. This commemorates those who were buried up country in the earlier part of the campaign in East Africa –

"Here are recorded names of officers and men who fell in East Africa before the advance to the Rufiji in January, 1917, but to whom the fortune of war denied the known and honoured burial given to their comrades in death."

The later casualties are commemorated by a similar memorial at Dar es Salaam.

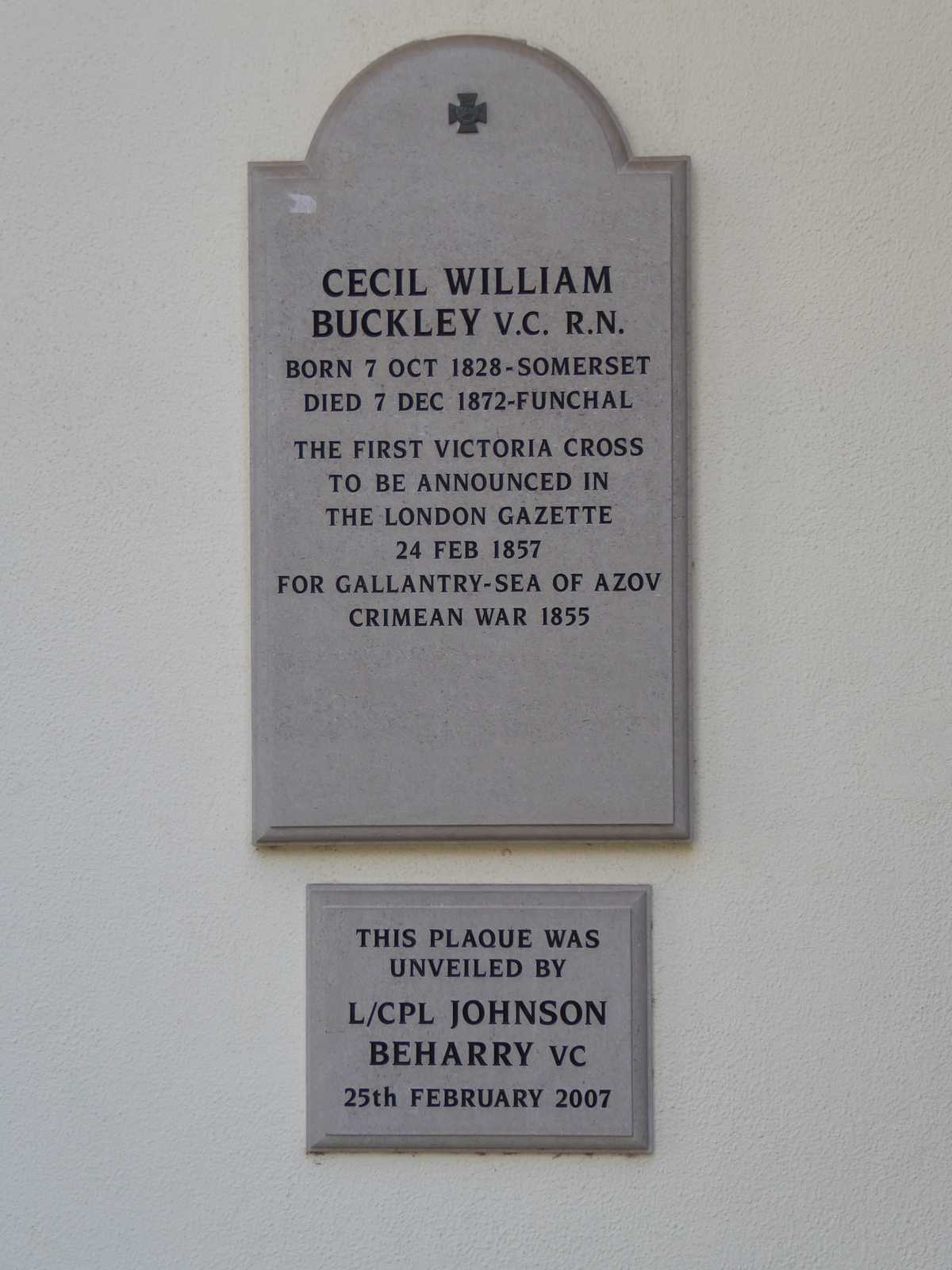

Another plaque on the church is not from WWI but is nonetheless interesting:

“Cecil William Buckley, VC, RN, born Somerset 7th October 1828, died Funchal 7th December 1872, the first Victoria Cross to be announced in the London Gazette, 24th February 1857, for gallantry, Sea of Azov, Crimean War 1855.

This plaque was unveiled by L Cpl Johnson Beharry, VC, 25th February 2007”

There are also three WWII graves in the English cemetery, which incidentally has many international graves. The three WWII ones are as follows.

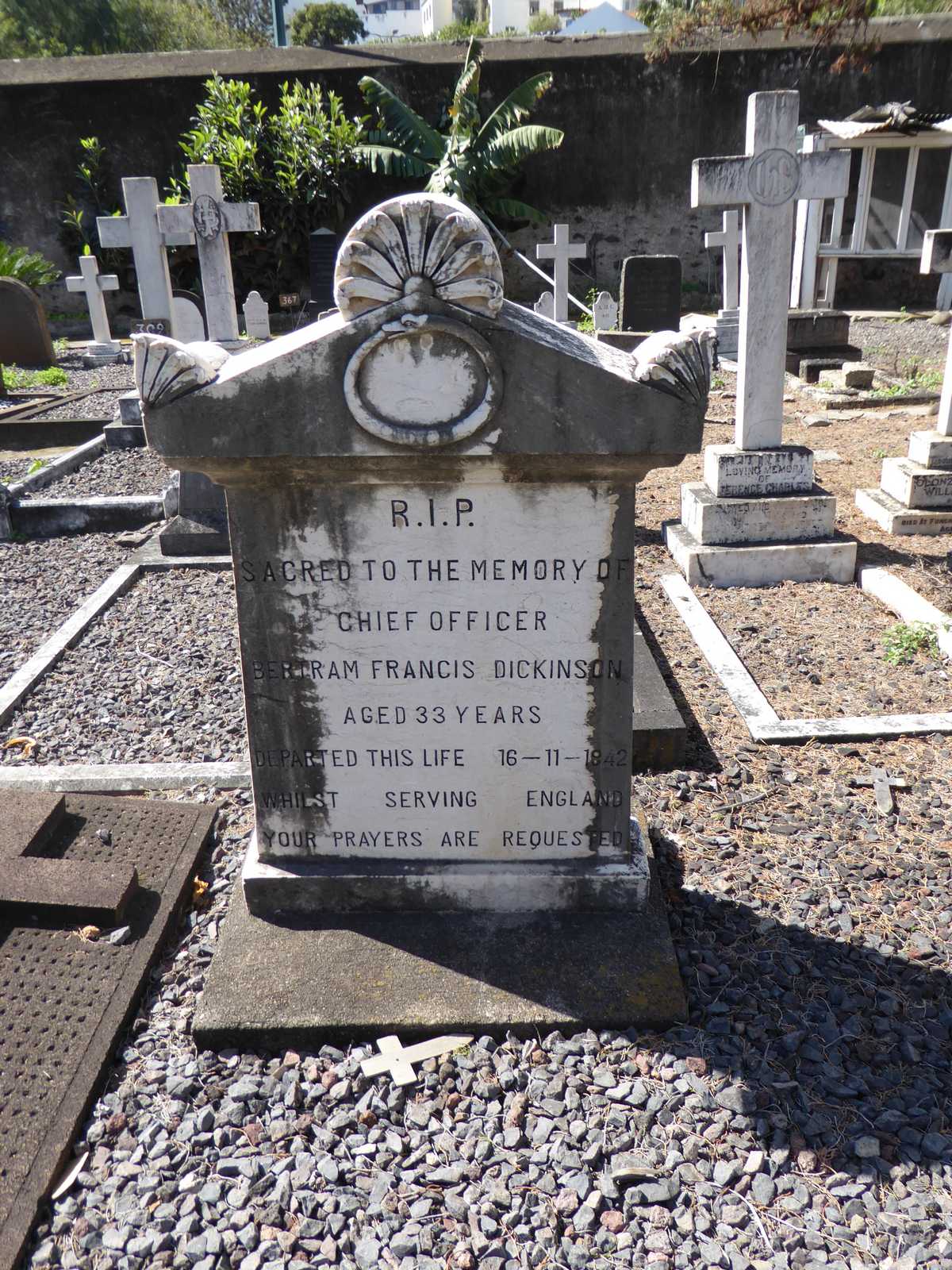

Chief Officer Bertram Francis Dickinson, Chief Officer, Merchant Navy, age 33, SS Bulmouth, 16th November 1942.

John Benjamin Smith, Donkeyman, Merchant Navy, age 42, SS Bulmouth, 7th November 1942.

It looks as if these two were injured in the same accident, or enemy action, or fell ill with the same disease.

Stanley Cuthbert Strang, Cadet, Merchant Navy, age 18, SS Corinaldo, 29th October 1942. His CWGC entry records that he was awarded the King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct and the Lloyds’ Medal for Bravery at Sea. Whatever his brave act was, it seems to have resulted in his death. The SS Corinaldo was attacked by U-509 on 29th October 1942, so it must have been that incident. Some of the crew survived, and clearly Strang made it as far as Madeira, dead or alive.

From the top - Chief Officer Dickinson, Cadet Strang and Donkeyman Smith

From the top - Chief Officer Dickinson, Cadet Strang and Donkeyman Smith

The Fall of the Ottomans

The Great War in the Middle East 1914-1920

Eugene Rogan

Allen Lane, UK, 2015

My wife had come across this book some time ago, and had thought it to be the most worthwhile one on the topic. At the time, she was researching the fate of an ex-patriate British lady in the Ottoman Empire. Neither of us then knew anything about the author. In fact, Eugene Rogan is professor of Modern Middle Eastern History at St Catherine’s College, Oxford. His writing is lucid and very easy to follow.

The Ottoman Empire comprised immense ethnic diversity, including Arabs, Kurds, Greeks and Armenians, and a variety of religions, including Shia and Sunni Muslims, Jews and a variety of Christians. The Empire covered the modern Middle East and more. Professor Rogan has opined that if the Ottoman Empire had not been dragged into World War One, it could still exist today and we would have a stable Middle East.

Many people will automatically think of the Gallipoli disaster when they consider Ottoman Turkey in World War One. Professor Rogan’s great uncle and his best friend were both fatalities at Gully Ravine. The British and Commonwealth fatalities were 3,800 but on a visit there the author discovered a memorial to the Ottomans’ 14,000 fatalities, a figure which is often ignored by British sources.

Much of the philosophy of attacking Ottoman Turkey was to knock it out of the war. In fact, Turkey stayed in the war until the last few weeks. Not only was the resolve of the Ottomans grossly underestimated but Gallipoli provided Turkey with its first victory in decades. They had lost a war against the Greeks for Greek independence, against Italy for control of Libya, the two Balkan Wars, against Russia in the Caucasus, and had ceded control of Cyprus and Egypt to Britain and of Bosnia-Herzegovina to Austro-Hungary, amongst other disasters. Gallipoli was when the tide turned, thanks to the incompetence of the Entente powers. It also was the foundation of Mustafa Kemal’s reputation as a leader.

Gallipoli was not the only theatre for the Ottomans. They fought the western Entente powers in Mesopotamia, Syria, Transjordan, Palestine, Sinai, Egypt, and the Hijaz, and the Russians in the Caucasus. These campaigns diverted hundreds of thousands of Entente troops from the western front and served to lengthen the Great War.

The major upheaval in Ottoman politics in the early 20th century was the Young Turks, a group of army officers, who rose in rebellion in 1908 against the autocratic regime of Sultan Abdulhamid II. The Young Turks were a popular “new broom” but their actions ultimately lead to their own deaths and that of millions of others.

The declaration of a holy war, a “jihad”, in November 1914 was envisaged by the Ottomans as a means of uniting their varied empire against the Entente powers. In religious terms, it was slightly odd in that it called for a war against some non-Muslims, ie France, Britain and Russia, but not against others, ie Germany and Austro-Hungary. The British and French saw the jihad declaration as being a ploy to unsettle their Muslim colonial subjects, but that seems to have been, at best, only a secondary objective of the Ottomans.

At the end of the war, the Young Turk leadership fled Istanbul at night to escape the anger of their own people on whom they had brought suffering, and now the indignity of an Allied occupation. The new Turkish regime sought to assuage the wrath of the Allies by convening tribunals to try the perpetrators of the Armenian massacres. Figures cited in the Ottoman parliament for the massacres ranged from 800,000 to 1.5 million. The tribunal process started in January and March 1919 with arrests of three hundred Turkish officials. The process petered out in August 1920. Eighteen officials were sentenced to death and three were actually executed. The proceedings of these trials has existed in the public domain in Ottoman Turkish since 1919, and, as the author states, make a mockery of attempts to deny the role of the Young Turks’ government in ordering and carrying this genocide. Several of the key figures then in exile were hunted down and killed by members of the Armenian Dashnak organisation. The only member of the ruling triumvirate to escape assassination was Enver who was killed in a battle near Dushanbe in the Tajik-Uzbek border region, leading a Muslim militia against Bolsheviks in August 1922. By 1926, ten of the eighteen condemned men were dead, with the others left looking over their shoulder for the rest of their days.

The “follow on” war where Mustafa Kemal routed foreign armies from Turkey and established the modern state is only dealt with in summary, as that event took place after 1920, the cut-off date for this book. Nonetheless, his seminal role in post-WWI Turkey is recognised.

The conclusion of the book reflects on the relative absence of commemoration of the centenary of WWI in the Middle East. Indeed, there is little perception today in the countries that were carved out of the Ottoman Empire that they and their citizens were involved in the conflict at all. There are, for example, few war memorials. Perhaps the real commemoration is the turmoil which many of those countries are in.

To quote Professor Rogan’s final words in the book:

“Yet as the war is remembered in the rest of the world, the part the Ottomans played in that conflict must be taken into account. For the Ottoman front, with its Asian battlefields and global soldiers, turned Europe’s Great War into the First World War. And in the Middle East more than in any other part of the world, the legacies of the Great War continue to be felt down to the present day”.

If you are interested in WWI in the Middle East, this book is a key to much of it.