The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have an article on the differences between the Spanish flu and Covid-19, articles on the RAMC in WWI, and on the Brodie helmet. The first article is by Caroline who is a retired doctor. The two subsequent articles are by courtesy of Terry Jackson who is the ex-chair of the Lancashire and Cheshire branch, which meets in Stockport. Trevor

The 1918 ‘Flu Pandemic and Covid-19: a Comparison

Dr Caroline Adams

Editor’s introduction: Our WFA President, Professor Gary Sheffield, wrote in the most recent edition of “The Bulletin” that the Spanish ‘flu and Covid-19 were different and, if WFA members could do nothing else, they could spread that message. Here, Caroline gives us her overview of the differences and similarities.

How does the 1918 ‘flu pandemic compare to the current Covid-19 pandemic? I have no doubt that not one, but several books will shortly appear on that subject, but here are a few of my own thoughts on the matter.

The two diseases are caused by viruses from very different families - influenza viruses and coronaviruses. The ‘flu virus is seasonal. Coronaviruses tend to be present in high numbers all year round. ‘Flu viruses have been endemic in human populations for centuries. They mutate freely, so one year’s ‘flu may be worse than another’s but the antigens are similar. In the 1918 pandemic, therefore, older people often already had appropriate antibodies and most deaths were in young adults. In contrast, Covid-19 appears to be completely novel in humans. No one has pre-existing immunity and the death rate is highest in older people. So, the list of differences could go on and on. They are biologically-different organisms causing different diseases.

But they both have each caused a viral pandemic and that is where the main similarities lie. There is no cure and no vaccine. They have both caused illness, death and fear, inadequate action and over-reaction, governments struggling to appear in control, sound scientific advice and fake news.

At first glance, there is not a lot of similarity between 1918 troop ships and 2020 cruise liners. We have discovered, though, that both are very good virus breeding grounds. A cruise ship’s cabins are way more luxurious than troop ship accommodation, but when the ventilation system cycles air round the ship, the viruses travel round too. That situation is not over – there are thousands of cruise ship crews still marooned at sea.

In both pandemics, people have clutched at straws, looking for an effective treatment. In 1918 it was aspirin. In 2020, it was hydroxychloroquine, though I think we have discredited that much quicker than massive doses of aspirin were stopped in 1918. We do, thankfully, have better developed systems today for assessing drug efficiency and working on vaccines but, in 1918, as in 2020, the way to avoid infection with a respiratory, droplet-spread virus is to avoid contact with other people: ‘Stay at home. Wash your hands. Save lives.’

The 1918 ‘flu hit developing countries hardest. The current pandemic is at an earlier stage in some countries than in others, so the numbers are not in yet. It is obvious, though, that the spread will be higher in communities where housing is too crowded to ‘socially distance’ and where those who don’t work, don’t eat. Shanty towns and refugee camps will be badly hit. If you don’t have access to a hospital with an intensive care unit, the chances of surviving a severe infection are reduced, and they are even lower if you have no access to a hospital at all. As with any disaster, man-made or natural, it is the poorest who come off worst.

And what of the long term consequences? The 1918 pandemic killed predominantly young adults, the bread-winning generation, at a time when the war had already killed millions of young men. The demographics of Covid-19 will at least leave us with most of our working age adults. There will be workers to fill the jobs. It remains to be seen how many jobs there will be for workers.

Will we learn the lessons of this pandemic? Exploiting the natural world has enabled viruses to jump species. Lack of preparation for a pandemic, despite warnings, has hindered our response, as has poor co-ordination and co-operation between countries. Will we do better in the future? What lessons did they learn about disease management in 1918, and have they been forgotten?

The development of the RAMC in WWI

Terry Jackson

Dr Jessica Meyer, Associate Professor, Leeds University recently gave the Lancashire and Cheshire Branch an in-depth account of how wounded soldiers were treated on the Western Front. This is an account by Terry of that talk. There is further information on Jessica’s work at the end of this account.

The first aid for a wounded soldier was his own dressing pack. These were very basic, but gave the soldier a degree of comfort. Casualties would either walk or be brought to the Regimental Aid Post situated in their trench lines and would receive initial first aid

Regimental Aid Post (RAP)

The RAMC (Royal Army Medical Corps) chain of evacuation began at a rudimentary care point within 200-300 yards of the front line. Regimental Aid Posts (RAPs) were set up in small spaces such as communication trenches, ruined buildings, dug outs, or a deep shell hole. The walking wounded struggled to make their way to these whilst more serious cases were carried by comrades or sometimes stretcher bearers. The RAP had no holding capacity and here, often in appalling conditions, wounds would be cleaned and dressed, pain relief administered and basic first aid given. The Regimental Medical Officer in charge was supplied with equipment such as anti-tetanus serum, bandages, field dressings, cotton wool, ointments and blankets by the Advance Dressing Station (ADS) as well as comforts such as brandy, cocoa and biscuits.

If possible men were returned to their duties but the more seriously wounded were carried by RAMC stretcher bearers often over muddy and shell-pocked ground, and under fire, to the ADS, sometimes via a Collecting Post or Relay Post to avoid congestion.

Regimental Aid Post

Advanced Dressing Station (ADS)

These were set up and run as part of the Field Ambulances (FAs) and would be sited about four hundred yards behind the RAPs in ruined buildings, underground dug outs and bunkers. In fact, anywhere that offered some protection from shellfire and air attack. The ADS did not have holding capacity and though better equipped than the RAPs could still only provide limited medical care. Here, the sick and wounded were further treated so that they could be returned to their units or alternatively, were taken by horse drawn or motor transport to a Field Ambulance. The Main Dressing Station (MDS) roughly one mile further back did not at first have a surgical capacity but did carry a surgeon’s roll of instruments and sterilisers for life saving operations only.

In times of heavy fighting, the ADS would be overwhelmed by the volume of casualties arriving and often wounded men had to lie in the open on stretchers until seen to. ADS would also have comforts such as brandy, cocoa and bandages, field dressings, cotton wool, ointments and blankets. If possible, men were returned to their duties but the more seriously wounded were carried by RAMC stretcher bearers often over muddy and shell-pocked ground and under shell fire, to the Field Ambulance, sometimes via a Collecting Post or Relay Post to avoid congestion.

In times of heavy fighting the ADS would be overwhelmed by the volume of casualties arriving and often wounded men had to lie in the open on stretchers until seen to.

Advanced dressing station

Field Ambulance (FA)

These were mobile front-line medical units for treating the wounded before they were transferred to a Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). “Field Ambulance” is not an actual vehicle – it refers to an RAMC unit. Each Army Division would have three FAs which were made up of ten officers and 224 men and were divided into sections which in turn comprised stretcher-bearers, an operating tent, tented wards, nursing orderlies, cookhouse, washrooms and a horse drawn or motor ambulance. Later in the war, fully equipped surgical teams were attached to the FA and urgent surgical intervention could be performed to sustain life. By the autumn of 1915, some FAs had trained nurses posted to them.

In these early stages men were assessed and then labelled with information about their injury and treatments. As in a Casualty Clearing Station, medical officers had to prioritise casualties using a procedure known as triage. Many of the wounded were beyond help; morphine and other pain killing drugs were the only treatment. (Note: “triage comes from the French word to organise or sort out, and is a system first devised by Napoleon’s surgeon general).

Casualty Clearing Station (CCS)

These were the next step in the evacuation chain and are situated several miles behind the front line, usually near railway lines and waterways so that the wounded could be evacuated easily to base hospitals. A CCS often had to move at short notice as the front line changed and although some were situated in permanent buildings such as schools, convents, factories or sheds, many consisted of large areas of tents, marquees and wooden huts often covering half a square mile. Facilities included medical and surgical wards, operating theatres, dispensary, medical stores, kitchens, sanitation, incineration plant, mortuary, ablution and sleeping quarters for the nurses, officers and soldiers of the unit. There were six mobile X-ray units serving in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and these were sent to assist the CCSs during the great battles. CCSs were often dangerously vulnerable with large depots containing munitions and supplies alongside which were targeted by enemy aircraft and artillery. (Photo left: Australian CCS at Grevillers).

A CCS would normally accommodate a minimum of fifty beds and 150 stretchers and could cater for 200 or more wounded and sick at any one time. Later in the war, a CCS would be able to take in more than 500 and up to 1000 when under pressure. In normal circumstances, the team would consist of seven medical officers, one quartermaster and 77 other ranks, a dentist, pathologist, seven QAIMNS (Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service) nurses and non-medical personnel. Major surgical operations were possible but sadly, men who had survived this far often succumbed to infection. The CCSs were usually in small groups of two or three to enable flexibility. One might treat cases for evacuation by train, ambulance or waterways to the base area, leaving one free to receive new casualties and another was able to treat the sick who could be moved, in order to receive battle casualties in an emergency.

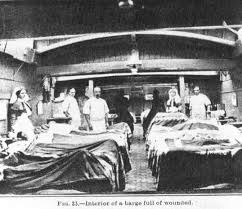

Australian CCS at Grevilliers

Initially, the wounded were transported to the CCS in horse-drawn ambulances – a painful journey and, over time, motor vehicles or even narrow-gauge railways were used. Often the wounded poured in under dreadful conditions, the stretchers being placed on the floor in rows with barely room to stand between them. The admissions and evacuations were incessant and almost all that could be done in the time was to feed the patient and dress his wounds. One of the greatest boons was the provision early in 1915 of trestles on which the stretchers were placed. Comforts such as sheets, pillow cases and bed socks were obtained from such organisations as the BRCS (British Red Cross Society). As the number of casualties grew, so the need for experienced staff increased. In the first Battle of Ypres, difficulties were highlighted with an influx of between 1,200 and 1,500 casualties in twenty four hours and in the Battle of the Somme of July 1916 there were between 16,000 and 20,000 casualties on the first day of the offensive. By August 1916, selected CCSs had as many as twenty five nurses on the staff.

Gas was first used at Ypres in April 1915 and thereafter as a weapon by both sides. Patients were brought in to the CCS suffering from the effects and poisoning of chlorine, phosgene and mustard gas, amongst others.

The seriousness of many wounds and infection challenged the facilities of the CCSs and as a result their positions are often marked today by military cemeteries. Kate Luard was posted to a number of CCSs including one as Head Sister of No.32 CCS which specialised in abdominal wounds. It became one of the most dangerous when the unit was relocated in late July 1917 to Brandhoek to serve the push that was to become the Battle of Passchendaele. She had a staff of forty nurses and nearly 100 orderlies.

From the CCS, men were transported en masse in ambulance trains, road convoys or by canal barges to the large base hospitals near the French coast or to a hospital ship heading for England. Back home, men would be sent to a local hospital unless they needed specialist treatment. These would often be schools or similar institutions

The Victorian Building on the junction of Greek Street (in Stockport) and Royal George Street was used as a Military Hospital (diagonally opposite the TA) as was Alexandra School further down Castle Street.

The system worked for the early years of static trench warfare, but in the 100 days advance it was increasingly difficult to move the aid facilities forward to keep up with the progress of the front line units.

A fascinating study of probably the most essential non-combative service in the Great War

Terry Jackson

Jessica Meyer’s book “An Equal Burden: the Men of the Royal Army Medical Corps in the First World War” is available from OUP and as a free download from the OUP website - here

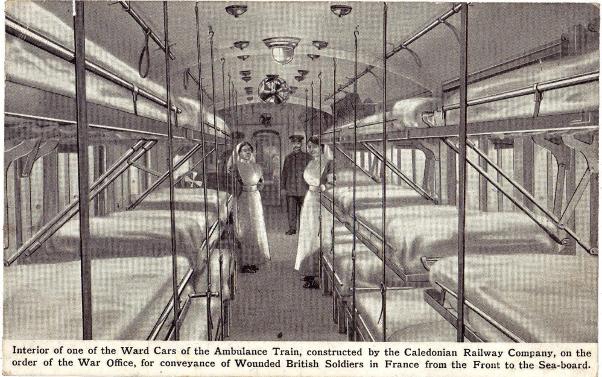

An ambulance train

An ambulance train

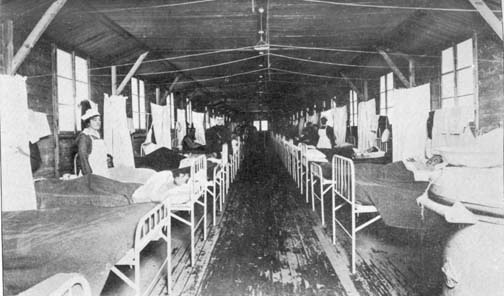

A hospital barge

A base hospital

A hospital ship: HMHS Brighton

The Brodie Helmet

Terry Jackson

At the end of the Victorian era following the Boer wars and several Empire campaigns, the British army had realised that the old red tunic with white cross belts was an easy target for the modern high velocity smokeless bullet. Thus the Khaki uniform evolved, being less obtrusive. It was accompanied by a soft cap.

The 1914 war was expected to be short and one of movement. However, by the end of the year, the European theatre had evolved into a stalemate with two frontline trenches facing each other from Belgium to Switzerland. The Germans were in enemy territory, so, realising the outflanking fighting was leading to the prospect of a siege in the field, dug in whenever they found the high ground. Their attitude to the enemy was if you want your land back, fight for it, but we have the better positions. They also quickly learnt the value of trenches on reverse slopes.

The Allies were not fully geared for a huge offensive in an attempt to push the enemy back and trench warfare commenced. Trenches offered relative safety. Rifle shots would only succeed if a soldier exposed himself. So, the most effective way of attacking the enemy was by shell fire. High explosive was obviously fatal, but was costly in material terms. A simpler way to kill or injure the enemy was by the use of shrapnel. In the standard field gun (e.g. French 75mm), a shrapnel shell would contain 270 lead ball-bearings. A time fuse ignited explosive from the rear in the air and thrust them out in a deadly cone. (In actual footage one can observe the white cloud of the shell and then further along see the dust raised as the shrapnel bullets hit the ground). (Photo above right– a Brodie helmet)

This was an ideal way to attack soldiers in trenches. The balls would cause fatal and other wounds, especially to the head and upper body. To counter this, the French were the first to adopt protective headgear. It is generally held that a French officer, Adrian, initially suggested a metal skull bowl to be worn under the soldier’s cap, after he had learnt that a soup bowl under a cap had saved a poilu’s life. Subsequently, the Casque Adrian was developed based on traditional headwear. However, it had faults. It was made in several pieces with a riveted crown piece, which could break. Nevertheless, it did provide some protection.

The British realised they needed some form of helmet. Several inventors offered prototypes. In June 1915 a design by John Leopold Brodie came to their attention. Brodie had anglicised his name when he moved from Latvia. The model (of which there were 2 types, A & B- the former being adopted) was a basic one-piece bowl and rim similar to helmets of the pre industrial era. A liner was attached by a small screw on the top. It was to be made of mild steel.

Initially, an order for 850 per day was made to Army Navy Co-operative Society Ltd, as it was simple to make. However, on reflection, the Army decided manganese steel would be better as it could offer protection against shrapnel travelling at up to 750 feet per second.

Unfortunately, there was only one steelworks that could meet this requirement. Also, this type of steel is particularly brittle in a stamping process. This meant that whereas one million mild steel helmets could be made in less than 3 months, it would take up to 6 months for manganese models (Firth and Sons).

Fortunately, Firth and Sons indicated that following trials with the firm Beardmore & Co*, a specialist naval armour company, the figure could be met. This could be done by Firth and Sons, Hadfields Ltd, Beardmore & Co*, Mirris Steel Co, and Joseph Sankey and Sons**. The Army & Navy Co-op would then assemble the liners. (Many of the companies were based in Sheffield with one in Scotland ship yards* and another in Bilston**). Slight modifications were made for ease of production.

Helmets were first introduced to the Scots Guards in mid-November 1915. Earlier, on 9 August at Hooge, the Official History 1915 Vol 2 p.109, indicates a few helmets were used, but in the early morning mist they were mistaken for the enemy and were fired at by comrades.

By mid-March 1916, 270K helmets had been made but only 140K had arrived on the Western Front. There was an initial scare when head wounds appeared to have increased, until it was realised that this number reflected those who would have otherwise received fatal wounds. A study at Ypres during the Battle of the Bluff on 2 March 1916 showed all head wounds had reduced by 75% compared to figures prior to the introduction of the helmet. Haig was impressed and demanded that all his soldiers were issued with the helmet. By the first day of the Somme, one million helmets were in use in France. The helmet was popularly known as the “Battle Bowler” or the “Tin Hat.”

Some improvements were necessary after the introduction of the helmet, following feedback from their wearers. The liner was uncomfortable and difficult to adjust. The painted surface reflected light and the rim was sharp and could injure a comrade. Improvements were made. The liner was improved, helmets were dulled with sawdust and a crimped border reduced the sharpness of the rim.

Experiments were made with chain visors to protect the eyes, but could cause disorientation and were not popular. Eventually, all troops were provided with the helmet and production continued until the end of the war. Colonial troops and the Americans used the helmets - the latter eventually producing their own version. In September 1917, Home Command Units were issued with them as they tackled the Zeppelin and Gotha menaces. (Photo right – casque Adrian)

The Brodie remained standard equipment in the Second World War, mainly with improvements to the liner and adjustable straps. (A simpler model was adopted for paratroopers, having no rim). By the time of D-Day a new model was beginning to be introduced, being a deeper bowl and from its shape known as the “Turtle.” Film footage shows these being used mainly by Canadians on D- day. After the victory in 1945, it became the standard issue for British forces and stayed in service until the introduction of the ballistic nylon helmet of 1985.

Most armies now use synthetic helmets, the Americans initially using Kevlar. However, in the hi-tec. world of today, improvements are constantly being made and the specifications are being continually updated. Body armour is also now much lighter and can be worn as standard equipment.

Terry Jackson

Editor’s note: Terry has been an affectionado of helmets since trying on his grandfather’s WW2 Civil Defence Zuckerman helmet, as a small boy. His collection includes: GB - Brodie WW1, WW2 'Turtle; Zuckerman, WW2 Paratroop, Ballistic Nylon, BN Paratroop; French Casque Adrian WW1, Adrian WW2; German WW1 & WW2; USA WW2 & Post WW2 Kevlar; Italian; and French, Japanese, and Russian WW2.