The Dragon’s Voice

In this issue, we have an article on WWI connections in the cemeteries on the Great Orme in Llandudno, some photos of Mark in fancy dress and three book reviews. As ever, we owe many thanks to Jim Morris for allowing us to use his WWI day by day material on the Facebook page.

Trevor

The Programme for 2017

Oct 7th : John Stanyard : Under Two Flags, the Salvation Army in WW1

Nov 4th : Jane Austin: News from Nowhere: a talk based on her recently-published book about family letters sent from the Western Front back to Bangor

Dec 2nd : Branch Social

Last Month’s Talk

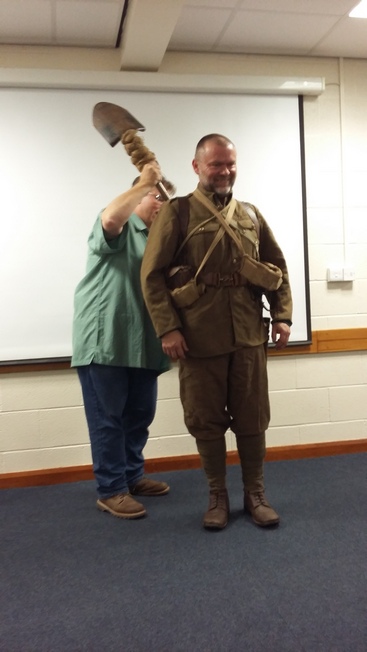

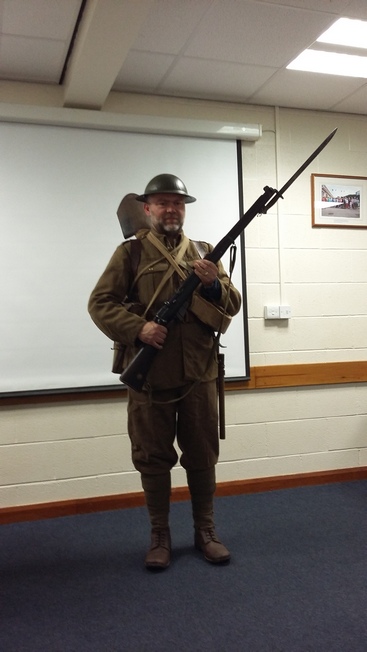

Taff Gillingham made the long trek from East Anglia to talk to us about the Khaki Chums, which can only be described as a group of hardened WWI enthusiasts who take it to the extreme of marching on the Western Front in authentic kit. This lead on to the second aspect of the talk which was on the developments of the soldiers’ kit over this period. We have some photos of Mark as the tailor’s dummy at the end of this newsletter!

Up on the Great Orme

Trevor Adams

Taking advantage of recent mild weather, and a decreased number of tourists, Caroline and I went in search of the grave on the Great Orme of a gentleman that I think I have mentioned here before,

In 1920, he joined a law firm in Trinity Square in Llandudno, now Swayne Johnson, where he stayed for the rest of his life. He was, incidentally, instrumental in the setting up of the tennis courts at the community centre, as it now is, where our branch meets in Craig y Don. He was the local Boy Scouts commissioner and secretary of the Llandudno association. He died suddenly in 1946.

The website “History Points” has information on the location of the graves of “interesting” local people in the Great Orme municipal churchyard, and I should add that there is also the St Tudno’s church graveyard beside it. Well, thanks to that site we found Major Parke’s grave without much difficulty (see photos).

However, he is not the only WWI casualty there. Mrs Mary Ann Johnson was killed when the RMS Leinster was torpedoed on 10th October 1918 (see photo below right). Ironically, the family had moved to Wales from Kent to avoid the danger of air raids. She had been visiting her daughter in Dublin. The family were clearly of some substance, as most of the recovered casualties from the Leinster are buried in Dublin. The official figure for the fatalities is 501, though the true tally is believed to be higher. On the Old Colwyn war memorial, Corporal John Williams is listed. He also died on the Leinster and is buried in Grangegorman military cemetery in Dublin.

David Cynnelw Williams, d1942, was a WWI chaplain who won the MC for rescuing and tending  wounded soldiers. He was one of only 14 Welsh Calvinist ministers to serve in WWI. He unveiled the Penmaenmawr war memorial in 1925. He was chaplain of the local Toc H branch.

wounded soldiers. He was one of only 14 Welsh Calvinist ministers to serve in WWI. He unveiled the Penmaenmawr war memorial in 1925. He was chaplain of the local Toc H branch.

Wandering around, we found a new CWGC headstone. I know from being with Steve and Nancy in western front cemeteries that this was a computer-cut stone. It is on the grave of Pte FR Newbery, King’s Liverpool Regt, dod 25th April 1920. The CWGC will put a headstone on a grave where the original family stone has perished or is illegible. This does require the consent of the graveyard authorities, which has obviously been granted here. I gather from the CWGC head of external relations that this consent is sometimes not forthcoming, believe it or not, and he named the Church of England as being notably difficult due to their extensive bureaucracy. The CWGC grave registration report form states: “died at 101 Rowson Street, Wallasey. Address: Normanhurst, Malom Road, Llandudno, aged 22”.

On the same grave registration report are listed (and marked as private memorials, ie not CWGC ones, so hard to locate even if the marker is still there today):

- Corporal Caradoc Evans, RWF, dod 30th June 1918, died at Kinmel Park, Rhyl

- Pte John Jones, RASC, dod 31st December 1920, died Ministry of Pensions Hospital Bangor

- Pte Sam. Chris. Boyce, RWF and Labour Corps, dod 9th October 1919, died 1 Wyddfyd Cottage, Great Orme, age 29

- Pte Albert Poole, South Lancs, dod 11th October 1919, died at Birkerley Cottage, Vardre Lane, Llandudno, aged 31

- Lt Eric Noel Pearce, RNR, 19th February 1921, died Hook (Hoole?) Chester, address Holme Dale, Church Walk, Llandudno. This has been struck through in red ink as “not a war grave”.

In fact, from the CWGC website, there are 38 casualties there, both WWI and WWII, along with four in St Tudno’s churchyard. These will have been largely, or entirely, private memorials.

In St Tudno’s churchyard, graves which are of particular interest in the WWI context are:

- Aldwyth Katrin Williams – the only daughter of the rector of Llanbedr-y-Cennin. She enrolled as a VAD in the early days of the war, serving in Llandudno convalescent homes, the Red Court and the Balmoral. She died of influenza on 8th November 1918, aged 26. The funeral cortege through Llandudno was joined by nursing staff and patients from the Balmoral.

- Harry Lawrence Oakley – the subject of a talk to our branch and a short article in an earlier edition of this newsletter (..\..\2016\dv copy\Dragon's October 2016.doc). He served in the Green Howards, finishing as a captain. He was a silhouette artist and his wartime drawings were published, including some used for recruiting posters. He ran a booth on Llandudno pier from 1922, doing on the spot silhouette portraits. Two of my neighbours in Rhos had their portraits done by him. He died in 1960.

- Mary Edith Nepean – born in Llandudno in 1876, she served as Red Cross nurse in WWI when she lived in Folkestone and commanded the detachment there. She wrote 30 novels, the first in 1917 “Gwyneth of the Welsh Hills” being made into a film in 1921 starring Madge Stuart and Lewis Gilbert. She died in 1960 and sadly there were only four mourners at her funeral.

- Guy Everingham – dod Easter Sunday, 8th April 1917. He enlisted in the RWF in 1914, and trained in Llandudno where he met his wife. They lived at Lynwood, St David’s Place, Llandudno. At the time of his death, he was a 2nd Lt in the RFC, serving as an observer. His plane was shot down by von Richtofen in the lead-up to the battle of Arras. Both observer and pilot are buried at Bois Carre CWGC cemetery. The stone in St Tudno’s churchyard is a memorial plaque to him on a family plot, presumably his wife’s family. His brother Robin was killed in 1915 in Gallipoli. Both are remembered on the war memorial in Llanidloes.

Well, it is surprising what you can find on your own doorstep. According to the CWGC there are a huge number of war graves in the UK, though as many will have private memorials some are not easy to find in a cemetery, but keep looking!

Trevor Adams

References

Book reviews

“The Vanquished: why the First World War failed to end, 1917 – 1923”

Robert Gerwarth

I came across this book when looking for another book on Amazon and thought it looked interesting. It is indeed. The writing style is very readable and not at all “academic”. Robert Gerwarth is the professor of modern history in University College Dublin.

Perhaps the following quote from the introduction gives a flavour of the subject:

“For those living in Riga, Kiev, Smyrna or many other places in eastern, central and south-eastern Europe in 1919 there was no peace, only continuous violence.”

The war may have ended for Britain and France and other major powers in November 1918 but that is certainly not the case for other participants, or for those who were unfortunate enough to be just caught up in it. This was a period of widespread political upheaval as had not been seen in Europe for 200 years.

“Between 1917 and 1920 alone, Europe experienced no less than 27 violent transfers of political power, many of them accompanied by latent or open civil wars.”

The most obvious example is the Russian revolution and subsequent civil war that cost three million lives. Indeed, a feature of these wars is the persecution, torture, mass-murder and ethnic cleansing of civilian populations, who in themselves were a key target of the often ill-disciplined, anarchic forces involved in the conflicts. These included the German Freicorps “helping” their allies in the Baltic states, and communists everywhere who regarded the elimination of supposed “enemies of the revolution” as a key component of their aim of creating a new world order. This era saw the rise of communism and fascism. Hitler, incidentally, started off on the extreme left before going to extreme right.

Border conflicts and ethnic disputes were factors in this era. The Polish state of the era fought aggressive wars on various fronts. The wartime Polish “Blue Army”, which had been part of the French army, became the central part of the post-war army of the new Poland, which of course had not existed as a single independent country for two hundred years. Between November 1918 and 1921, the Poles fought wars against the Russians, Belorussians and Ukrainians to the east, Germans to the west, Lithuanians to the north, Czechs to the south, and Jews as “internal enemies” on territory it already controlled. A key issue was the question of where the borders lay, and often in this period the realities on the ground were more important that what was decided in the post-war political decisions by the Great Powers.

The blotted copybook from the British, and indeed Welsh perspective, was the Asia Minor War between Greece and Turkey (though do not let us forget that the allied naval blockade which stopped food supplies reaching civilians in many countries in central Europe continued through the period of the peace negotiations). Lloyd George, and Churchill, had encouraged the Greeks to attack Turkey to seize parts of the former Ottoman Empire. However, Turkey had a very able army commander in Mustafa Kemal and he was determined to ignore whatever had been imposed on Turkey in the Treaty of Sevres, as part of the Versailles process, and did so very effectively. This was an horrific war with attacks and massacres of civilians by both sides, such as the massacre of 30,000 civilians in Smyrna in 1922, whilst British and French warships sat in the harbour and did nothing. Ernest Hemingway was one of the Western reporters present to record the horrible events.

Lloyd George had wanted to re-start WWI against Turkey but Canada and Australia refused to countenance such a step. The Conservatives in the coalition government bowed to public opinion which was very much against re-starting the war, and Lloyd George’s government fell on 19th October 1922. This was the “Chanak” crisis. Andrew Bonar Law succeeded Lloyd George and he appointed Lord Curzon to negotiate a settlement.

Eventually, a conference at Lausanne was arranged in 1923 between Britain, France, Turkey, Bulgaria, Greece, Italy and Soviet Union, and so was unlike Versailles where the Axis powers were not involved in the negotiations. The Treaty of Lausanne brought an end to the fighting, and led to the so-called exchange of populations where Greeks were expelled from Turkish territory and Muslims were expelled from what was now Greek territory. This exchange included the Pontic Greek population on the Black Sea coast who had been there since 700BC. Anatolia and eastern Thrace remained Turkish, in contrast to the Versailles imposed “solutions” of dividing Turkey amongst the Western powers, and also the creation of Armenian and Kurdish states was shelved.

The Middle East conflicts of today have their roots in this period as well. The Western Powers decided on the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire, not into new states for the benefit of the citizens of that region but instead as a colonial carve-up between France, Britain and Italy, the effects of which we are still living with today.

Perhaps the telling epitaph of this so-called “inter war” period is that at the outbreak of WWII in 1939 there were fewer democracies in Europe than there had been at the start of WWI in 1914. So, what did WWI and the Treaty of Versailles achieve? One may wonder.

Trevor Adams

“Little Grey Partridge”

First World War Diary of Ishobel Ross

who served with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals unit in Serbia.

Aberdeen University Press

ISBN 0 08 036419 5

Ishobel Ross was born in 1890 and grew up on the Isle of Skye. She was educated at Edinburgh Ladies College and Atholl Crescent School of Domestic Science and taught cookery at an Edinburgh girls’ school. When the Great War started, she made bandages with the Red Cross in her spare time, but in 1916 she heard about the Scottish Women’s Hospitals at a talk by Dr Elsie Inglis and she decided to volunteer with them. This book is a transcript of her diary from leaving home in July 1916 until her return to Britain in July 1917 and was published by her daughter several years after Ishobel’s death. It includes a fascinating collection of photographs.

I came across a reference to this book when reading about the Scottish Womens’ Hospitals, and I bought it despite a very damning review that appears on the Cambridge University Press website. I am pleased to report that I whole heartedly disagree with that review! It criticises the poor description of surrounding events and lack of deep analysis of her own reactions, but this totally misses the point that this is a personal diary, written for herself. It is a brief contemporaneous record of what Ishobel did and what she wanted to remember. Its value is that it is spontaneous and unselfconscious and as such gives us a picture of day to day life in the hospital and how one young woman coped with it. I totally disagree with the accusation that Ishobel makes it sound as if life in the hospital was ‘equivalent to a Girl Guide camp’. I do not think that a cook at a Girl Guide camp would have reason to record ‘The Bulgars are lying around the hillside unburied, and I am going up to bury some of them tomorrow’, or be required to assist in the operating theatre because of a shortage of nurses!

The war is, in fact, the constant backdrop to all of Ishobel’s writing, the sound of bombardment from the front line, the constant passing of troops of various nationalities, the arrival of the wounded, the funeral parties that passed her kitchen on the way to the hospital cemetery. It is all understated, but she had lived through it and would not forget. She did not need to record the detail. Of particular interest are the number of visitors to her kitchen, officers and men taking any opportunity for a moment of homely comfort and even some POWs managing a few minutes relief from a workparty constructing the road. She also met Serbian royalty and Flora Sandes, the British woman who fought with the Serbian army.

Equally understated are the conditions in which she worked, the intense cold, the snow and the mud in the winter, the heat in the summer and at times cooking in the open air because of lack of a kitchen building. One ‘building’ when it was ready was, in fact, only made of rush matting. Ishobel also takes for granted that the staff were expected to speak French and Serbian. After lessons on the journey out, her Serbian rapidly became fluent with constant practice talking to the Serbian orderlies, patients and visiting officers. Later, she was also taught some Russian by one of the patients.

The most detail, however, is given to describing the socialising and fun which the staff of the Scottish Women’s Hospital managed to create. I suspect that this is what offended the Cambridge University Press reviewer! To me, however, this is a vital part of the picture. It gave meaning to a life lived in awful conditions and surrounded by the suffering and often death of their patients. It cemented friendships, not only between the staff but also with the Serbian army and civilians. Any visit to the town for supplies was an opportunity to have coffee with the local Serbian officers, even if you had to push the lorry through the mud on the way back! The mutual affection and respect between the staff of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals and the Serbians is clear. The title of the book comes from the Serbian nickname for these brisk, efficient women in their grey uniforms, ‘little grey partridges’. The final entry in the book is a letter to Ishobel from Captain Mikail Dimitrivitch of the Serbian army, in 1918. It is also evident from current Serbian commemorations of the First World War that these ladies are not forgotten there.

I thoroughly recommend this book to anyone who has ever wondered how the ladies of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals coped and why so many of them remembered their time in Serbia with affection.

Caroline Adams

“Nurses of Passchendaele”

Christine E Hallett

Pen and Sword 2017

s/b 196 pages, Illustrated, £12.99

“The Ypres Salient saw some of the bitterest fighting of the First World War.

The once-fertile fields of Flanders were turned into a quagmire through which men fought for four years. In casualty clearing stations, on ambulance trains, and at base hospitals near the French and Belgium coasts, nurses of many nations cared for these traumatized and damaged men.

Drawing on letters, diaries and personal accounts from archives all over the world Nurses of Passchendaele tells their stories, faithfully recounting their experiences behind the Ypres Salient in one of the most intense and prolonged casualty evacuation processes in the history of modern warfare. Nurses themselves came under shellfire and were vulnerable to aerial bombardment and some were killed or injured while on active service.

Alongside an analysis of the intricacies of their practice, Christine Hallett traces the personal stories of some of these extraordinary women, revealing the courage, resilience and compassion with which they did their work”

So reads the back cover of this book, I had to read it!

Christine Hallett is Professor of Nursing History at the University of Manchester. She is a trained nurse and practised in the North of England before she moved into teaching and research.

The book is not just about the nurses. It explains the reason for the Battle of Passchendaele. She tells how important to the Belgian people was that little piece of Belgium that was known as the Ypres Salient. The ultimate aim of the battle was to try and reclaim the Belgian ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge. She even mentions the plans for an amphibious landing on the coast of Belgium (operation hush) east of Nieuwport. We now know that this plan did not happen, and the battle turned into one of the worst in the war for conditions and casualties.

Of interest to me was the planning of the medical support, and the decision to move three casualty clearing stations so close to the front line. The casualty clearing stations were grouped in threes. When one was full of casualties it closed, and then the next station took in casualties. They rotated them.

Also how the conflict of the VAD's and the trained nurses was up to a point resolved. The book talks about all of the other nationalities involved. The American doctors and nurses were the first to go into the front line, weeks before any of their fighting troops. To the great surprise to the British, some of the American nurses were trained as anaesthetists but this led to some of the British nurses being trained as anaesthetists, so relieving the doctors of that work. (Editor’s note: by this stage there were a thousand American doctors in the BEF, including as battalion medical officers.)

The book covers all the aspects of the injuries inflicted on the soldiers, not just the terrible wounds but also the gas victims and the problems of the conditions that the men were in, eg trench foot, trench fever and some of the illnesses and infectious diseases the men suffered. It also explains the development of the medical teams, how they improved over the course of the war, and how doctors and nurses worked in teams, on a shift pattern to cover the twenty four hours. The three casualty clearing stations No 44 British, No 32 British and No 3 Canadian which were formed as the Advanced Abdominal Centre were situated at Brandhoek, very close to the front line. This enabled the doctors to treat the patients within one hour of them been wounded. It was at Brandhoek in these casualty clearing stations that one of my heroines, staff nurse Nellie Spindler was killed on the 21st August 1917 in a shelling and bombing attack by the Germans. The account of this in the book is very well documented.

The book features many of the well-known women of WWI - Kate Luard, Edith Appleton, Kate Maxey, Minnie Wood, Elsie Knocker and Mairi Chisholm. The resilience of the nurses comes out in their humour. They gave names to some of their casualty clearing stations: No 46 was known as Mendinghem, No 47 as Dozinghem and No 62 as Bandaghem.

Sister Kate Luard was visited by Sir Anthony Bowlby, Consulting Surgeon to the BEF whose idea it was to move the casualty clearing stations close to the front. On a visit to Brandhoek, he said to her

“How d'you like the site this time? Front pew, what? Front pew, dress circle”. He may have thought it funny but Kate's reply is not recorded. One American nurse, a Miss Gerhart, was so liked and respected by the British that they first called her “American Sister” but later this changed to the more affectionately “Cat-Gut-Katie” .

The book is very well researched and written, with a full Bibliography and Index. It is a wonderful and inspirational read and at £12.99 a bargain. I highly recommend it.

Keith Walker

Just Another Soldier?

As we crouch in the trenches, waiting for the call

Men suffer all around me, brothers one and all

Now, all of a sudden, we’re about to stand

And we’re running blindly through No Man’s Land

Jumping over dead men, thinking of my home

Friends dying all around me, mouths bubbling with foam

And then

Terror! Searing pain! Shattering my arm

I dare to glance, hoping there’s not too much harm

I’m starting to fall, bullets screaming past my ears

My brothers dropping round me, I’m fighting back tears

Thinking of my family, I’m lying in the mud

My strength is failing me, as the ground soaks with my blood

Is this it? Is my life over? It’s only just begun!

I’m fading fast, God help me! I think my time has come

Finn Henderson (12)

Ballymena Academy, Ballymena

from Pam

RWF Exhibiton at Wrexham Library

There is an exhibition running from now until the 6th January at Wrexham Library on the RWF in Palestine and Egypt. Entry is free.

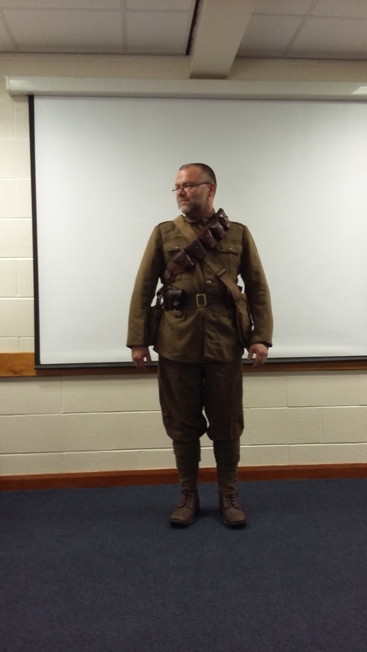

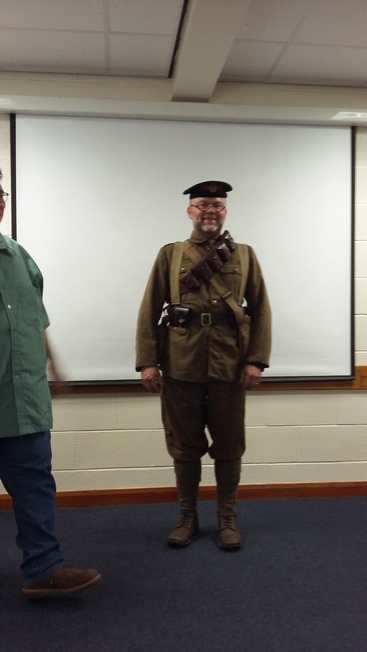

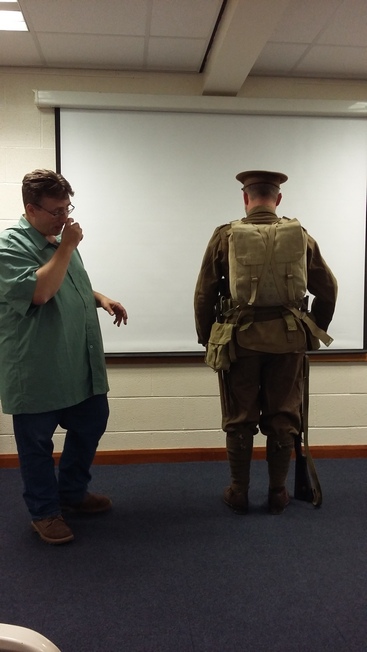

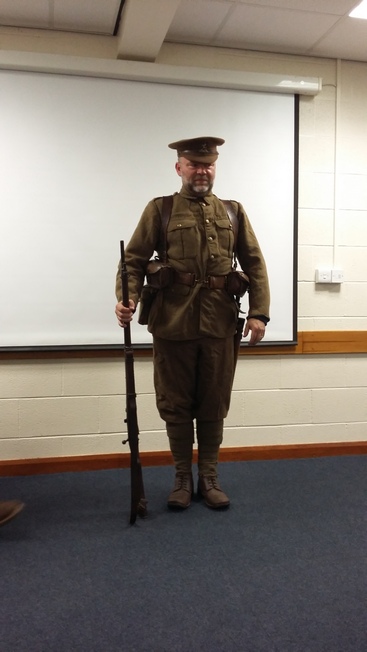

Photos below

This is a series of photos of Mark acting as the stooge for Taff’s exposition on British army webbing design. This starts with the 1903 pattern which came in after the second Boer War, complete with a quasi-beret. This pattern of webbing had lots of different components and was somewhat cumbersome. It was replaced by the more familiar, to us, 1908 pattern made of fabric which was much easier to wear. At the same time the SMLE Lee Enfield came in, which was less cumbersome than the Lee Metford.

With the Kitchener recruits joining up in WWI, production of 1908 webbing could not keep up, so leather webbing was re-introduced (8th photo below). In the rest of the photos, we see Mark with the WWI soldier’s kit of pack, bayonet, entrenching tool, cloth pouches for ammunition, steel helmet and a rifle.

Photos above, right, and immediately below are 1903 pattern webbing The 1908 pattern cloth webbing, photo above and below

The 1908 pattern cloth webbing, photo above and below

The Kitchener recruits' WWI leather webbing, photo above and the ones below

The complete WWI infantryman