Book Review

The First World War Diary of Noël Drury

6th Royal Dublin Fusiliers

Gallipoli, Salonika, Palestine and the Western Front

Edited by Richard S Grayson

Army Records Society

Boydell Press, 2022

The Army Records Society produces an annual volume of the papers of, usually, a soldier who is well-known and which is edited by one of their esteemed academic historians, though sometimes the topic is a bit more wide-ranging than one person’s papers. This particular volume has been eagerly awaited for rather longer than intended, due to the Covid pandemic and the consequent suspension of publishing operations. The editor of the present volume is the professor of 20th century history at Goldsmiths College, University of London.

The story of Irish soldiers in WWI is one that has been hidden until comparatively recently, especially the history of the Southern Irish soldiers. In fact, 200,000 soldiers from the island of Ireland volunteered for service with Irish regiments. The late Professor Keith Jeffrey estimated that a further 50,000 served with other British army regiments and with the Canadians, Australians, Americans, New Zealanders and other Entente armies. At the time of Noël Drury’s death in 1975, the issue of there having been soldiers from what is now the Irish Republic serving in WWI was ignored by Irish officialdom, and unknown by the general public. The memory was kept alive by the families of those who served, and those in the Irish Defence Force with an interest in their own history.

The approach of the centenary of WWI, and Northern Ireland Peace Process, saw a new interest in WWI, not least as an example of Irishmen, and women, from all over the island working together. Our WFA colleagues in the Republic have worked hard to raise awareness of this aspect of Irish and British history. All this has led to a plethora of books on Ireland’s role in WWI, including ones on key figures with Irish connections, and those who are less well known. (Kitchener and Gough are two of the well-known ones). So, the “forgotten” diaries of a Dubliner who served in a regiment that has not existed for 100 years have now seen the light of day, some 45 years after they were deposited in the National Army Museum.

A word on the three Irish divisions in WWI is perhaps called for. The Division number of the Irish Divisions indicates their political background, in that the 10th was neutral and was formed first, as it was least trouble. The 16th was Redmond’s Irish nationalist volunteers, and the 36th was the Ulster Division, the core of which was Carson’s protestant militia, though not forgetting that there was a substantial contribution from the members of the Catholic community in the North.

I discussed with the historian Stephen Sandford, who wrote a history of the 10th (Irish) Division, that the division was rather kicked around the globe by the powers that existed at the time. Stephen said that indeed they were treated as being disposable, but for the average soldier the odds of him surviving the war were in fact better in the 10th than the 16th or 36th.

Noël Drury (1884-1975) was from a middle-class Dublin Protestant family and served most of the First World War as an officer in the 6th Royal Dublin Fusiliers (“RDF”) in the 10th (Irish) Division. The 10th Irish division was the first of Ireland’s wartime volunteer formations to be posted overseas, arriving at Gallipoli in August 1915 in the Suvla Bay landings. Drury and his battalion experienced several key phases of the Gallipoli campaign before being redeployed to Salonika in October 1915 (in fact into the mountains, while still being issued only with tropical kit). Drury was away from the battalion for a year in 1916-1917 suffering from malaria, but re-joined in Palestine towards the end of 1917. From there, his battalion was sent to the Western Front in the summer of 1918 to take part in the Hundred Days Offensive. Drury’s diaries describe training, daily life, contrasting theatres of war, and show what it meant to be an Irish officer in the British army. He was also a keen motorcyclist in his youth and took part in the Isle of Man TT races before WWI, and car races after the war. His younger brother Kenneth was a doctor who served in the army from August 1914 throughout the whole war, winning an MC in 1916 and finishing as a major. Noël Drury’s diaries were donated by his family to the National Army Museum in 1976, after his death.

For all his genuine Irish credentials, Drury had been educated at the public school of Mill Hill in North London, which was founded to take non-conformist pupils. Thus, it was unlike most public schools which only took either Anglican or Catholic pupils, as the case may be. The Drurys were Presbyterians. So, his writing is that of an English public school boy – who else would use the word “scrimshanking”? It means a shirker, by the way. He is therefore in the same category as Max Staniforth, who was with the 16th Irish Division and whose letters were also edited by Professor Grayson, ie they were both from an Anglo-Irish background. This is to the detriment of neither of them, as both authors write lucidly.

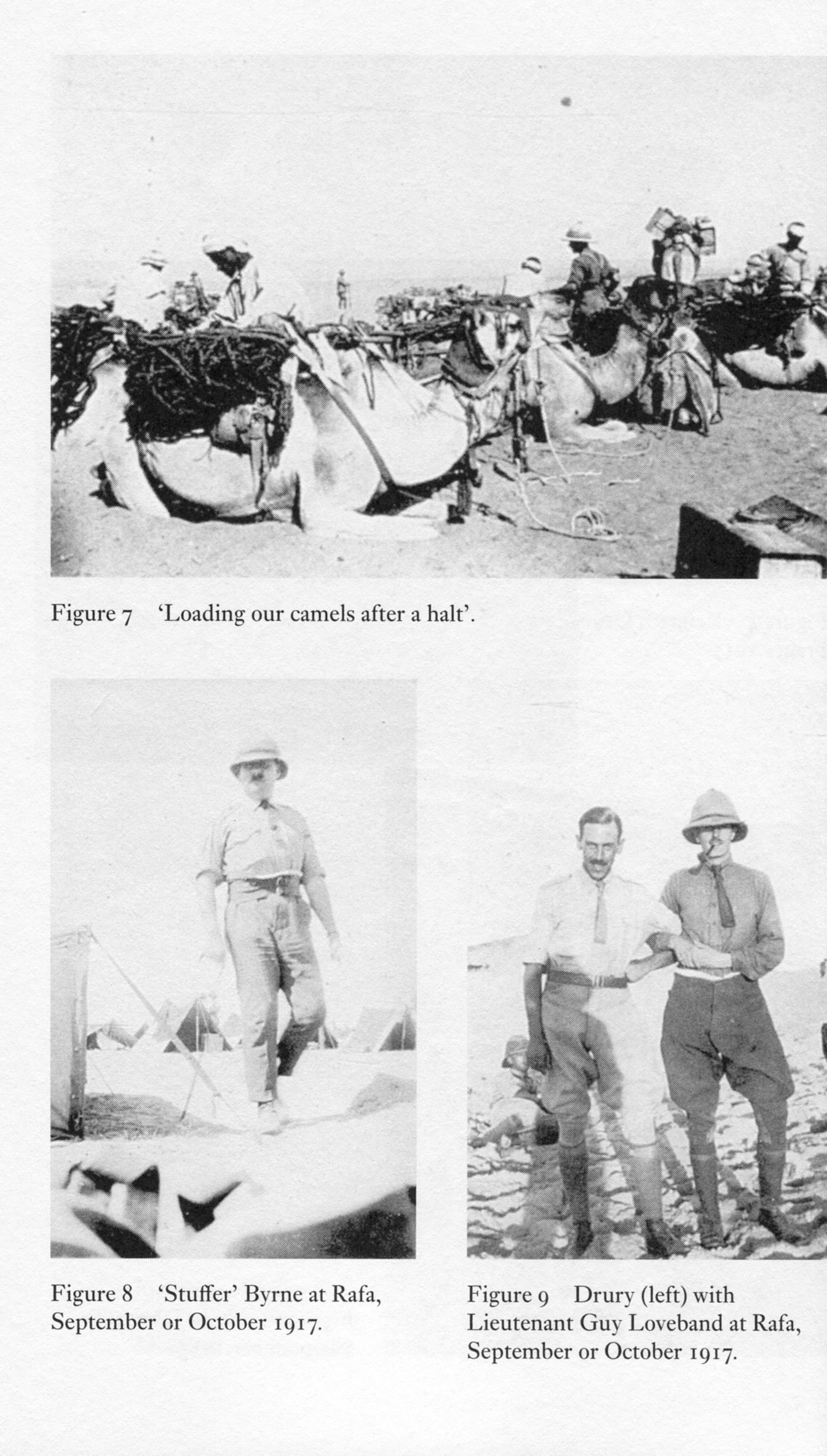

The book contains some photos of where Drury was during the war, of his fellow officers and of the man himself. It also has some wonderful words of the era and army slang, eg the Connaught Rangers were referred to as the “common dangers”.

The 10th Irish, or at least it component parts, ended up in four different theatres in WWI. After initial training, they were sent to Gallipoli via Gibraltar, Malta, Egypt and the Greek islands. The public school boy, trained in the classics, was fascinated to see some of the locations. Drury and his fellow officers tried to buy melons using Attic Greek which greatly amused the locals (as would someone in the UK trying to buy groceries using Anglo-Saxon). The voyages were not terribly pleasant in the warmer climates, especially at night when the portholes had to be kept shut for fear of the lights giving the ship’s position away to U-boats.

The arrival at Suvla Bay was to be a foretaste of the chaos of the Gallipoli campaign. The troops landed without orders and without maps. Drury is critical of the general staff for their lack of organisation. Indeed, anyone who thinks that the Gallipoli campaign could have been saved should read the first-hand accounts of people like Noël Drury.

His first experience of major action was an advance from Hill 50 towards Ali Bey Chesme. He writes “The firing was worse than I imagined it would be and I felt very scared”, with snipers hidden in trees being a particular problem. The attack failed and Drury attributed that to

“the failure by the staff to work out any proper scheme at the beginning while there was a chance of our getting there without much opposition” and “the extraordinarily bad behaviour of the 11th (Northern) Divn troops and some of the 53rd”.

The 6th Royal Dublin Fusiliers lost 11 officers and 259 other ranks, with 6 of the officers being killed, which required some reorganisation of the battalion. A subsequent attack on “KTS” ridge and a counter attack by the Turks saw more casualties. Drury was appointed adjutant which would give him greater insight into liaison between his unit and both 33rd Brigade and the 10th (Irish) Divn.

My personal interest is in the next phase of the diaries which deal with the move to Salonika on 10th October 1915. We were there a few years ago with Alan Wakefield and the Salonika Campaign Society. In Salonika, the 10th (Irish) were there to support the French in an attempt to protect Serbia from Bulgarian aggression. Drury was delighted to see Mount Olympus which had such significance to the ancient Greeks. The 6th RDF were sent north from Salonika (Thessaloniki) in November to Kosturino, a ridge high in the mountains. This is one heck of a climb to get up there today in good weather, never mind in December 1915 while carrying a lot of kit.

“It is impossible to get warm, everything is frozen solid. There were 42 degrees of frost last night – ten degrees below zero [= -23C]. We had an enormous sick parade this morning, nearly 150 men reporting. There were many bad cases of frostbite in hands and feet and ears.”

The 6th RDF were in reserve when the Bulgarians overran elements of the 10th (Irish) Divn holding the ridge on 6th December. They were covering the retreat of the French on 8th December, and saw heavy fighting. There is a certain lack of amusement on the part of Drury at the tardy French withdrawal, taking goods and animals removed from the civilian Serb population. The whole force was withdrawn to Doiran, just inside the then Serbian frontier, and then back to Salonika where they helped to construct the defensive “birdcage” line. Drury refers to his delight in seeing storks and wild tortoises, with which I heartily concur – they are definitely still there today. He also records the shooting down of a Zeppelin.

The 6th RDF had been reinforced by elements of the Norfolk regiment who apparently had a rather snotty attitude about being attached to an Irish regiment which, Drury points out, was old and prestigious having been first raised in 1641.

By May 1916, the allied forces were being extended north to Lake Doiran and the Struma valley. The heat at this time of year was oppressive. This area was subject to malaria (which has been eradicated since) and Drury did indeed contract that disease. He was eventually evacuated back to the UK for treatment for malaria and corneal ulcers. He was not back with the 6th RDF for a year.

He records the effects of the fire which destroyed much of old Salonika on 21 August 1917. The British soldiers and sailors helped the locals to evacuate whereas, according to Drury, the French and Italians got drunk on stolen wine.

In September 1917, the 10th (Irish) Divn were sent to Egypt and then to Palestine. He has a wonderful mention from his classical studies of Herodotus visiting the pyramids and describing them as being “very old” (sometime around 450BC).

The Palestine campaign was to protect the Suez Canal from the Ottoman forces which controlled the Middle East, as the canal was the gateway to the British colonies in the Far East. The 6th RDF saw little action in the first four months. They were in reserve for the Battle of Beersheba in October 1917, and were then holding positions round Gaza in early November. They did not take part in the attack on Jerusalem but had to protect the position from a possible counter attack, and spent “a miserable Christmas Day with chattering teeth and aching bodies”. Jerusalem is in the Judean Hills. He tells of later engaging a local guide to take him and his friend round the holy sites of Jerusalem.

His description of the fighting in Palestine is very much of an open country campaign, with the added problems of running ahead of your supplies, and co-ordination with other units, or even finding the other units.

In July 1918, the units of the 10th (Irish) were transferred to France. The division was “Indianised”, and stayed in Palestine but without the “Irish” designation.

In France, the 6th RDF was part of 198th Brigade in the 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Divn. Drury was in hospital for much of August with a recurrence of eye problems. He re-joined the 6th RDF on 16th September 1918 some 40 miles west of Arras. The fighting was very much a war of movement and often the heavy artillery, at least, could not keep up. So, the 6th RDF were regularly on the move, sleeping where they could in the ruins of buildings. On 7th and 8th October, the battalion was involved in fighting round Le Catelet, about 15 miles south of Cambrai. Drury noted “The enemy are now driven into open country and those of us who have been accustomed to open fighting feel much more at home than in the trenches.”

They were also involved in the attack on Le Cateau on the 17th and 18th October, along with the 2nd RDF who had fought there in August 1914. The war had now become one of pursuit, so there were no major engagements. When news of the armistice came, Drury could scarcely believe it, and as for the men “they just stared at me and showed no enthusiasm at all……..They all had the look of hounds whipped off just as they were about to kill”.

The final location of the 6th RDF was the Belgian town of Jemelle. Bizarrely, he discovered in Hastiere that the Germans had sold the locals a supply of Union Jacks with which to welcome the British! Drury secured home leave in January 1919. However, he found his brother Jack and sister in law ill with the Spanish flu. (Jack seems to have run the family business whilst his brothers were at war). When Drury was in London returning to Belgium, he received word of a deterioration in their condition. He was granted leave to return to Dublin but arrived after Jack had died. He returned to London and explained the situation to the War Office which gave him further leave. He was demobilised on 11th March 1919, without re-joining his battalion. The final entry is his diary reads “Doffed uniform and turned civilian again”.

The family paper making business seems to have run into financial difficulties in 1926 and closed. What he did for employment after that is not known. He died on 5th December 1975 at his home, in Foxrock, perhaps the poshest part of Dublin. He never married and shared his house in later years with a cousin, Winifred Drury, who seems to have been the person who donated Noël Drury’s diaries to the National Army Museum (or indeed we should say Captain Drury as he was known). Thanks to her and the Army Records Society, we have this first- hand account of the four theatres in WWI in which an Irish battalion was involved.