Why did World War One happen?

This article has its roots in a talk which I wrote for the Western Front Association branches in North Wales and in Dublin. More profoundly than that, it is been part of my search to understand World War I and especially its causes. This is a rather difficult task. However, it has unearthed much interesting material, hence it is presented here so others may access it. If the reader looks to no other parts of this article than sections 4 to 8, then they should get a good overview.

1.What to read?

There has been a plethora of material written over the decades on the causes of World War I. Indeed, the number of books is said to be over 25,000. One wonders who sat down to count them!

Luigi Albertini – “The origins of the war of 1914”

Perhaps the most profound of the early tomes is that of Luigi Albertini. It still holds its own. This is a work in 3 volumes. It has the advantage of an author who was able to communicate with many of the leading participants of the events in question, not long after the events themselves. He was editor of a major Italian newspaper and that status granted him access to key players in the events of July and August 1914. Of course, the biggest gap usually is the Russians, because of the 1917 revolutions and the chaos thereafter, resulting in the loss of historical material and also of key witnesses. The book was first published in Italy in 1941 and did not appear in English until 1952.

AJP Taylor – “War by timetable”

Alan Taylor was a high profile historian who was well-known in the 1960s and 70s. His books are always an interesting read, and his book “The Habsburg Monarchy 1815-1918: a History of the Austrian Empire” is certainly a fascinating analysis of a country central to the events of 1914. The book that we want to mention in this context is his “War by Timetable” where his basic thesis is that the incredibly complex mobilisation plans of the continental great powers were such that once they began to mobilise their troops the plans could not be stopped. Of course, in this era we are talking of transportation by rail and therefore the complexity of moving huge numbers of men, horses and materiel by train to specified destinations.

Michael Neiberg (US) – “Dance of the furies: Europe and the outbreak of WWI”

Michael Neiberg is an American historian whose book analyses the attitudes and feelings of ordinary Europeans in the period leading up the 1914 July crisis. In short, they neither wanted nor expected a war in the summer of 1914: “most Europeans had difficulty adjusting to the idea of a general war sparked by an issue as insignificant as the Balkans”. The book deals with the views of the people, rather than being an analysis of the politicians’ deeds. He dispels that notion that the European populations were a collection of rabid nationalists intent on mass slaughter, though the tone of the newspapers of the day is another matter.

Sean McMeekin – “The Russian Origins of the First World War”

Russia is, in many ways, the neglected factor in discussions about the outbreak of WWI. Key interests to the Russians were access to warm-water ports, ie ones that did not ice up in the winter and, consequent to that, access from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean for their warships, which was prohibited by Ottoman Turkey. The Russian sphere of influence was Eastern Europe, where they would collide with Imperial Germany, sooner or later. They needed allies in that struggle.

Jean-Paul Bled - “The wayward successor”

This is a book in German by a professor in the Sorbonne in Paris. It is a superb account of Franz Ferdinand and shows how he was a pragmatist who sought to keep the Hapsburgs in power, and an outsider to the court establishment.

Tim Butcher – “The Trigger: hunting the assassin who brought the world to war”

This book seeks to dispel the myths surrounding the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie. The key falsehood was that it was a plot by the Serbian government. In fact, the assassin, Gavrilo Princip, was a Bosnian Serb who collaborated with others including Bosnian Croats and Bosnian Muslims to effect the assassination. They were trained and supported by the Black Hand, a group of extreme Serbian nationalists (whose leaders were subsequently executed by the Serbian government in 1917, for treason).

German-language sources

With the centenary of WWI being with us as this is written, more German language sources have come to the fore, though you need to be able to read German or to find a translation. However, they often give a much better insight into the mind of the establishment of Imperial Germany.

2.Obstacles to Understanding

Inane books and authors

Unfortunately, there has been a plethora of books of variable quality published on the origins of WWI, with a surge to coincide with the centenary of the events in question. Some even manage to conflate the issues of WWII with the events of WWI. For example some bizarrely attribute anti-Semitic tendencies to a German army in WWI that itself had many Jewish soldiers. In fact, the Jewish communities in Eastern Europe were the ones which could be easily communicated with as they spoke Yiddish, in effect a German dialect. (See Vejas Liulevicius).

Typically, in some British books the British government of the era is portrayed as “white knights” riding to the aid of the distressed damsel, ie Belgium.

Propaganda – do people believe it today?

In short, it is quite surprising how often those who should know better regurgitate contemporaneous propaganda as if it were fact. Propaganda is very interesting and should be taken on board but recognised for what it is – a tissue of lies woven round a thread of truth.

Covering the Establishment’s back in UK

This is a very British problem. Sir Edward Grey, the foreign secretary of the day, is a case in point. He was a Wykehamist, ie an old boy of the “public” school at Winchester, and generations of other public school boys from there have covered his back, including, unbelievably, at the centenary in 2014. He was, as a journalist eulogised, the longest serving foreign secretary, having served since 1906. However, absent from the eulogy was that Grey didn’t go to foreign countries, including the British Empire. Whilst the King travelled widely, Grey only accompanied him once, on his only foreign trip, to France in May 1914, at the King’s insistence. We will see later in the article how he was absent from Whitehall for a considerable period of the crisis and did not take the advice from the professional civil servants in the Foreign Office. (For more on this see Niall Ferguson The Pity of War). A review in New Statesman of a book on Grey said: “Because Sir Edward Grey was such a nice man, historians have followed his contemporaries in excusing the reality that he was such a disastrous minister: arguably the most incompetent foreign secretary of all time for his responsibility in taking Britain into the First World War”.

19th century political background

The UK had not fought a European war for 99 years and in any event was focussed on the Empire. Germany had been pulled together to form a country, not least by the efforts of Bismarck. France was recovering from the internal chaos of the Paris commune and was subject to the continuous wrangle between the Catholic Church and secular state, and indeed anti-semitism.

Understanding the Europe of 1914

The Europe of 1914 was a very different place from today. Borders were different and populations were in different countries from today and also in some cases in different places. At the centre of Europe was the moribund Austro-Hungarian Empire, which still existed because the Great Powers feared what would happen if it was not there, with considerable justification if one looks at the events post 1918.

World War One aftermath – Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles is in many ways about vengeance rather than a new world order. Its version of events of 1914 should be viewed in that light. The treaties, plural, after WWI created as many problems as they solved, if one looks at the causes of WWII and more recently, the Balkan Wars and conflicts in the Middle East.

Stalin: WWII– NKVD, Soviet bloc

World War Two radically changed the European landscape and makes it even harder for us to envisage the Europe of 1914. There were frontier changes post-1945, most obviously those concerning the Eastern borders of Germany. However, there were many others, eg between Poland and the Ukraine. Harder to envisage are the changes in populations. The Holocaust removed much of the Jewish population from Europe but the efforts of the NKVD and the Soviet army murder battalions is often overlooked. The removal to exile and annihilation of civilian populations changed the human landscape of central and Eastern Europe, the numbers involved certainly running into millions though the exact count is unquantifiable, unless something emerges in the future from the Russian archives.

Languages

This is still a problem today, not only as documents will have been written in the language of the country concerned, but that names of places have changed from one language to another, or simply been altered. For example, Bratislava in Slovakia was known as Pressburg in the days of Austro-Hungary.

3.The best explanation? The Balkan Wars

Bismarck famously remarked that the next European war would be sparked off by something stupid in the Balkans. He also said it was not in Germany’s interests for the bones of single Pomeranian grenadier to be buried anywhere in the Balkans. Bismarck died in 1898.

The Balkans in 1912 was the interface between the Ottoman Empire and Christian Europe, and had been so for several hundred years. Vienna had been besieged by the Ottomans in 1683. However, the Ottoman Empire was now creaking and losing its grip. Bosnia-Herzogovina was annexed by Austro-Hungary in 1908.

The First Balkan War followed in 1912, when the Ottoman Empire was pushed back out of the Balkans by Serbia, Greece, Bulgaria and Montenegro. (This alliance had been formed under Russian auspices).

The Second Balkan War was started in 1913 by Bulgaria, which tried to snatch more of Macedonia than they had been awarded in the treaty negotiations after the first war. They lost the war, miserably, in two months.

So, by 1914 a third Balkan War was at the door. Tensions and ill feelings ran high between the former allies themselves, and of course Austro-Hungary has to be added to the mix. A Bulgarian war memorial in Southern Macedonia refers to WWI not as the 1914-1918 war but as the “1913-1918” war.

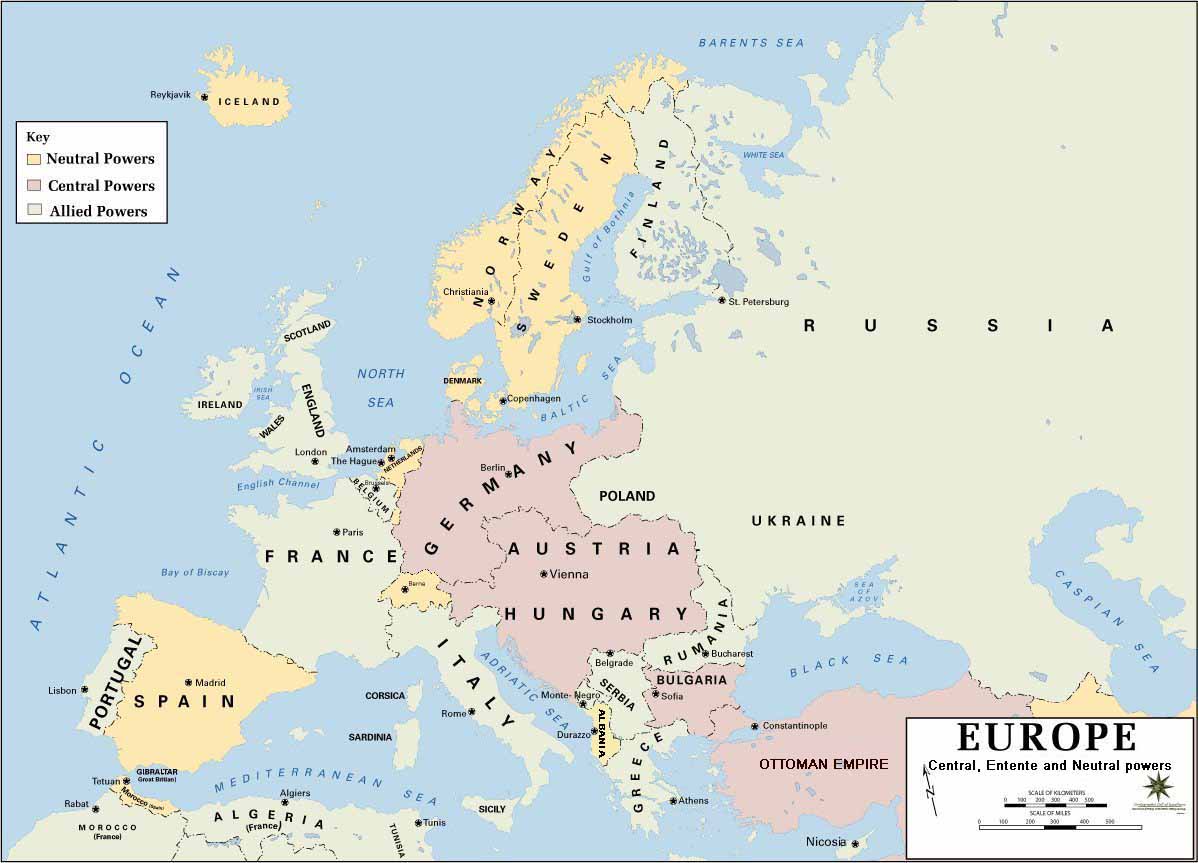

The Europe of 1914, with the Central Powers in lilac, the Entente Powers in light blue, and the neutrals in orange (from Dept of History, United States Military Academy)

Note: both Germany and Austro-Hungary are face to face over a border with the Russian Empire (Poland did not exist as an independent country)

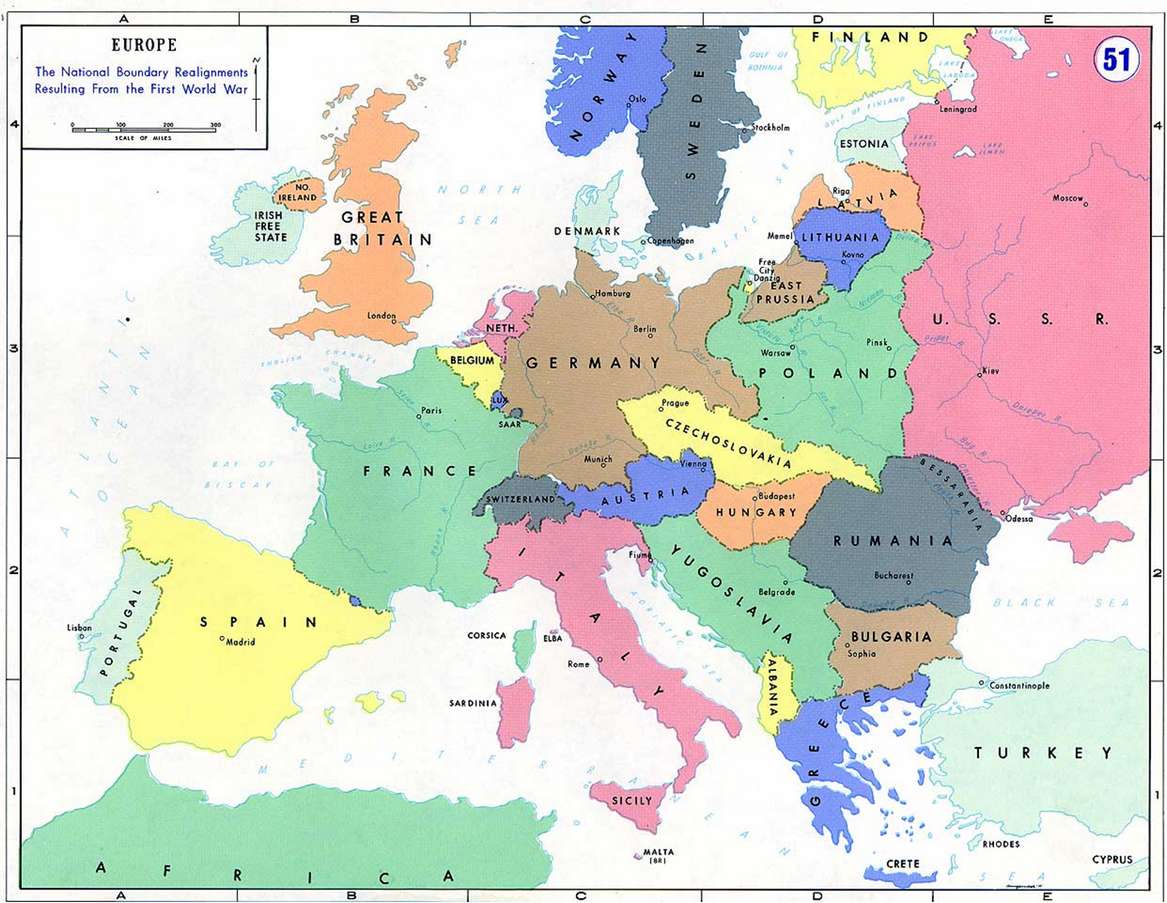

Europe post-WWI

Note that Germany, Austro-Hungary, Russia and the Ottoman Empire have lost territory and that Poland now exists

4.The schools of thought on why WWI happened

The best analysis of the differing theories of causes of WWI which I have seen is a paper from the University of California, Santa Barbara, though there is no author ascribed to it. It may be one of the student papers published on the internet by Professor Harold Marcuse of UCSB, or indeed it may be by the professor himself. (Sections 4 to 8 of this article are taken from the Santa Barbara paper). The url was http://www.uweb.ucab.edu/~zeppelin/originsww1.htm

In summary, the schools of thought can be described as:

A. International relations

1. Expansionist Germany

2. War a result of European “powder keg”

B. Domestic politics

1. the German elite wages war for imperialistic aims and to ameliorate social unrest

2. events outside Germany trigger war – includes elites of various countries

Let us look at these in turn.

5.A1 – International relations - expansionist Germany

This is the version in the Versailles Treaty, in effect “it was all Germany’s fault”.

Key scholars are:

Luigi Albertini, The origins of the war of 1914 (1952)

DCB Lieven, Russia and the origins of the First World War (1983)

Zara S Steiner, Britain and the origins of the First World War (1977)

AJP Taylor, several works

Albertini: he stresses the failure of diplomacy and much miscommunication as being major factors in the causation of WWI. However, he does state that German aggressiveness was also an important factor.

Lieven: he focuses on a bellicose Germany and a weak Tsarist regime under Nicholas II. The principal problem for Russia was a weak executive which was trying to maintain the royalist regime, despite Russia’s weakness when faced with an aggressive Germany. Lieven asserts that Russia was being defensive and that internal social unrest was a factor, as was Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese war 1904-1905. He maintains that Russia did not enter the war foolishly but saw things clearly. Germany’s militarism and its failure to curb Vienna leads Lieven to conclude that blame for the war lies “unequivocally with the German government”.

Steiner: she contends that Germany threatened British interests and that Britain responded defensively to German aggression.

AJP Taylor: “war by timetable”, where events are put beyond the grasp of statesmen by mobilisation timetables, ie once an army had started to mobilise the railway schedules were so complex that the mobilisation could not be stopped for fear of creating chaos. However, he blames Germany for disturbing the balance of power by its own self-aggrandisement and triggering its own encirclement by other countries, sparking off WWI.

6.A2 - International relations – “not Germany’s fault”

The common theory here is that the Europe of 1914 was a powder keg.

Key scholars are:

James Joll, The origins of the First World War (1992)

LCF Turner, Origins of the First World War (1970)

Paul Kennedy (Yale)

Joachim Remak, The origins of World War I (1967)

The common factors which created a war juggernaut which statesmen were powerless to stop are said by the various authors to be:

- militarism,

- mobilisation schedules

- a defective alliance system, and

- diplomatic blunders.

Militarism

War plans is the most common factor cited, notably Germany’s Schlieffen Plan (which we will deal with again, below). The German problem, so to speak, was to avoid having a war on two fronts, which was a situation they knew they could not win in the long term.

The plan hinged, literally, on pushing two million troops through Belgium and seizing Paris in eight weeks in a huge semi-circular movement. Do not forget troops of this era would be marching once they were on enemy territory, not riding on lorries or trains. The German army would have to capture the Belgian railway junctions immediately at the onset of hostilities, so their window of opportunity was a narrow one. Once the Russian army mobilised, the German army knew that they had to attack quickly, as a delay would be enough to ruin any chance the Schlieffen Plan had of succeeding. Indeed, it was an inept plan but those of other nations were worse.

The cult of the offensive was an important factor as well, that is the key thinking in military circles of the time was that the best form of defense was to attack the enemy first. In fact, none of them had realised that the balance of power had shifted with new propellants based on ammonium nitrate in 1880s, the Maxim machine-gun, and quick firing artillery like the French 75mm (see Norman Stone, The Eastern Front).

Ultimately, the cult of the offensive truncated negotiations in July 1914, as there was a perceived necessity to be able to strike the first blow.

The existence of the Schlieffen Plan in effect hastened the need for the mobilisations of the French, Russian and German armies.

Alliances

These were a destabilising factor by July 1914. The Anglo-French Entente Cordiale was vague and did not oblige the UK to go to the aid of France. The support for Austro-Hungary and Russia in their respective problems in the Balkans was noticeable by its absence (ie from Germany and France respectively).

Two relevant issues were (1) the need for Austro-Hungary to attack Russia at the same time as the Schlieffen Plan was implemented and (2) the need to prop-up weaker partners, ie Germany to prop up Austro-Hungary and Russia to prop up Serbia.

The Franco-Russian alliance gave Germany the feeling of being encircled and was a destabilising influence on Europe. Keenan argues that it was a military marriage of convenience between a Republican France and a Tsarist Russia that were political opposites and had different expansionist agendas. This alliance guaranteed that any Balkan quarrel could erupt into a great conflict.

Failure of diplomacy

In effect, the “powder keg” school of thought includes the diplomatic ineptness as a major factor (see Joll, The origins of the First World War). The incompetence of the Austro-Hungarian regime before, but especially after, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand is a major factor that is often undervalued. Remark blames Austro-Hungary in general, Serbia for failing to control the Black Hand and its associates, and Russia for failing to consider the consequences of its mobilisation.

The incompetence and corrupt nature of the Tsarist regime of Nicholas II is a major influence.

The obsession of France to recover its “lost” territory and avenge the ignominious defeat of the Franco-Prussian War is also often under-estimated.

7.B1 – domestic politics – “all Germany’s fault”

The central figure in this school is Fischer. The relevant works are:

Fritz Fischer, Germany’s aims in the First World War (1961/1967)

Fritz Fischer, From Kaiserreich to Third Reich (1979/1986)

VR Berghahn, Germany and the approach of war in 1914 (1993)

Wolfgang Mommsen, Domestic factors in German foreign policy before 1914

(1973)

Immanuel Geiss, German foreign policy (1976)

It has to be said that the Fischer viewpoint is redolent of German WW2 war guilt. He contends that the German elites wanted a war since 1912, based on domestic fears of the socialist successes in 1912 elections. In effect, they were trying to stave off democracy and the threat to their own privileged positions. The tactic was to use the Austrians and their casus belli, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, for starting a war.

The new, in 1961, archives revealed Bethmann Hollweg’s call for annexations and economic mastery over central Europe. Thus, a war would stave off democracy at home and bring about continental hegemony.

Fischer goes further and seeks parallels between German intentions in 1914 and 1939, which does seem to be a step too far. Overall, he attributes a lot of power over world events to a tiny elite in one country, which seems improbable. In any event, they were little different from their counterparts in other European countries.

Perhaps the biggest weakness is that Fisher this does not look at the culture of the time, in that war and nationalism were used to quell the working class in many countries. Bethmann Hollweg’s programme came after war had broken out, so was not a reason for starting a war.

Berghahn suggests that the rapid industrialisation gave power to working classes which was out of kilter with the existing political and social structure. Instead of social reform, the elite used the armaments industry and militarism to ameliorate social tension. In fact, the result was more social unrest.

Mommsen emphasises the malfunction of government and constitution which were at loggerheads with the modernizing forces of rapid industrialisation and mass politics. By 1914, the anachronistic Austro-Hungarian, German and Russian governments were unable to deal with the differing, rapid social changes in their own countries. The elites used nationalism and, ultimately, war to quell the working class.

8.B2 – domestic politics – “events outside Germany”

The basis of this school is that archaic forms of government and great social upheavals existed in all countries. The relevant works are:

Arno Mayer, Domestic causes of the First World War (1967)

Samuel R Williamson, Austro-Hungary and the coming of the First World War (1990)

Niall Ferguson, The pity of war (1999)

Mayer - In effect, nationalism and war were used to maintain status quo and fend off social change. All conservative European politicians consciously used popular nationalism and edged closer to war to preserve their social hierarchy from the rise of left and right-wing groups. His thesis is maybe over generalised but the point that policies and actions cannot be separated from their creators is often neglected.

He also identifies Austro-Hungary in particular as being a key problem.

Williamson – carries this argument forward and opines that Austro-Hungary’s role has often been neglected. It was a moribund empire composed of many ethnic groups, religions and languages. The decision-making was perverse and influenced by its own agenda in the Balkans, which was to see off a resurgent Serbia that threatened to foment trouble within the empire, and by Russia’s ambitions in the Balkans. They hoped for a local war to put Serbia back in its place, and that German backing would make the Russians back down.

Ferguson – points out that armament spending in Germany was lower than in the Entente powers and that the rise of socialist party was an indication of rising anti-militant sentiment. He places responsibility on the UK, not least as Sir Edward Grey slanted policy against Germany and grossly misread their intentions. Grey and his colleagues plunged the UK into the war to save their own political skins. Ferguson points out that the UK had planned to invade Belgium anyway in the event of a continental war. He puts forward the UK strategic plan, as expounded by Professor Stephen Badsey, that the UK had decided long before 1914 that they would need to protect the northern European ports from falling into one set of hands by going to war. Any navy based therein would be a major threat to the supremacy of the Royal Navy, which was the force that held the British Empire together.

The next section is here