The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have an article from a Canadian friend which was originally published in “Stand To” in the year 2001 about a “body-snatch” from the Western Front. Pam has sent us further extracts from the journal “20 Years On”. Finally, we have a review of an autobiography, or at least the first volume of it, of William Sholto Douglas about his time in the RFC and RAF in WWI. He was, of course, a senior RAF commander in WWII.

Trevor

The Programme for 2019

July 6th: Steve and Nancy Binks – Pilgrimage update

August 3rd: tba

September 7th: tba

October 5th: tba

November 2nd: tba

Mrs. Durie's Devotion

Gordon MacKinnon

A military funeral service was held at St. Thomas's Anglican Church, Huron Street, Toronto on Saturday, August 22, 1925. The deceased, Captain William Arthur Peel Durie, 58th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, had been killed in action in the trenches near Lens, France on December 29, 1917 and had already been interred in two military cemeteries. Exactly how his remains were removed from the Loos British Military Cemetery in 1925 is not known but there is no doubt that the removal was not authorized by the Imperial War Graves Commission, and that the persons who organized this illegal exhumation were Captain Durie's mother, Mrs. Anna Durie, and his sister, Miss Helen Frances Durie.

William Arthur Peel Durie was born in Toronto on August 8, 1881, the son of Lieutenant-Colonel William Smith Durie (1813-1885) and Anna Peel Durie (1856-1933). He seems to have been called "Arthur" by his family and "Bill" by some of his fellow officers. His only sibling was a sister, Helen Frances Durie (1885-1963). After attending Upper Canada College from 1893 to 1898 he was a banker for 15 years with the Royal Bank in Toronto until the Great War broke out. During this time he was unmarried and lived with his mother and sister on St. George Street in Toronto.

The "Fighting 58th" was one of the numbered battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force that was not broken up to be used as reinforcements for other Canadian units in England, France and Belgium. In February 1916, it was incorporated as one of the four battalions in the 9th Brigade of the 3rd Division, Canadian Expeditionary Force. From its arrival near the end of February in Flanders, it was involved in all of the major battles that the 3rd Division fought until the Armistice in November, 1918. Nearly 3000 casualties were sustained throughout this period. More than 900 were fatal.

The "Fighting 58th" was one of the numbered battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force that was not broken up to be used as reinforcements for other Canadian units in England, France and Belgium. In February 1916, it was incorporated as one of the four battalions in the 9th Brigade of the 3rd Division, Canadian Expeditionary Force. From its arrival near the end of February in Flanders, it was involved in all of the major battles that the 3rd Division fought until the Armistice in November, 1918. Nearly 3000 casualties were sustained throughout this period. More than 900 were fatal.

On May 5 1916, Lieutenant Durie was critically wounded at Zillebeke in the Ypres Salient when a bullet penetrated his right lung and came to rest in the pleural margin of his left lung. It was a nearly fatal wound because the bullet, which was never removed, missed the heart and major vessels that lie between the lungs. From May to November 1916, he was treated in military hospitals in France and England. Mrs. Durie had followed her son to Europe and was able to visit him in hospital.

After the fighting at Bellevue Spur, an offshoot of the Passchendale Ridge, on October 25-26 1917 the 58th required time to rebuild its depleted ranks but it was back in the trenches north of Passchendaele in November 1917. Appalling conditions resulted in large numbers of men becoming sick. By November 1917, it had returned to France and in the middle of December was in the Lens area. Captain Durie was granted leave of 14 days which he spent in England. He returned on December 22, 1917 to the trenches that the 58th now held in the Cité St. Émile sector at Lens. On December 29, 1917, during a fierce mortar attack, he was killed. He was buried in the Corkscrew Cemetery, Liévin, about four kilometres west of Lens (Row E, Grave 2). On February 20 1925, his body was exhumed by the Imperial War Graves Commission and reburied in Loos British Cemetery (Plot 20, Row G, Grave 19) as part of the consolidation of smaller wartime cemeteries.

Before World War I, there had been no British Army policy regarding the burial places of soldiers who were killed while on active duty. The dead were often buried in local cemeteries and frequently right on the battlefield. Bodies of those whose families could afford the cost were sometimes shipped back for burial in their home town cemeteries. When Fabian Ware began as a volunteer in the Red Cross to record the location of burial places of dead British soldiers in 1914, and learned that no official record was kept, he took the steps that led to the creation of the Graves Registration Commission and ultimately to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. In April 1915, the policy was established by the Commission of "equality of treatment after an equality of sacrifice”. The order forbade exhumations for repatriation on the grounds of hygiene and “on account of the difficulties of treating impartially the claims advanced by persons of different social standings."

Until April 1915, remains of some soldiers were occasionally returned to Britain for burial at family expense. The body of at least one Canadian, Captain Robert Clifford Darling of the 15th Battalion C.E.F. (48th Highlanders) who died of wounds in England on April 19, 1915 was repatriated to Canada without having been buried in England. It now lies in Toronto's Mount Pleasant Cemetery (Section V, Lot 89). The remains of Captain Durie, however, were removed from the Loos British Cemetery without the knowledge or permission of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Mrs. Durie used her Conservative Party connections in attempting to get her son's remains returned to Canada. The government of Prime Minister Meighen was unwilling to offer her any support. In 1921, an unsuccessful attempt was made to remove the body from Corkscrew Cemetery. Mrs. Durie and her daughter were in Europe at the time. A notice in the social column of Toronto's The Globe of June 17, 1921, states that "Mrs. Durie and Miss Helen Durie of St. George Street are sailing at the end of this week for England on route to France, where they will spend the summer" and another on August 22 notes that they "...have returned to Toronto from France where they spent the summer".

By 1925, the government in Ottawa had changed. Prime Minister Mackenzie King's Liberals had replaced the Conservatives. G.J. Desbarats, deputy-minister in the Department of Militia is quoted in the Liberal paper, The Toronto Daily Star on August 24, 1925 as saying "We have consistently set our face against the removal of bodies from the war zone. The bodies of those who died in France and Belgium are under the control of the Imperial War Graves Commission, and under an agreement with France and Belgium they are to remain in the country where they fell fighting together. As a matter of fact, quite recently a man who undertook to have the body of his son disinterred got into serious trouble with the Belgian authorities and the man who did the work narrowly escaped a prison sentence. I have not heard that the remains of Captain Durie were brought back. Certainly our policy is absolutely opposed to any removal of any bodies."

The Mail and Empire social column records that on August 17, 1925 "Mrs. Durie and Miss Helen Durie, St. George Street, were passengers on the S.S. Megantic from Liverpool yesterday after a short trip to France and England." Five days later the reburial of Captain Durie solemnly occurred.

The funeral on August 22 1925 was in three parts. There was a private ceremony for family and friends at the family residence, followed by a public funeral at St. Thomas's, Huron Street "crowded to capacity with men of the 58th Battalion and friends of the deceased." Pallbearers were some of the former officers of the battalion: Major W.E. Cusler, MC, Lieutenant-Colonel Dunham, Captain A.S. Brown, Colonel Dougall Carmichael, DSO [former CO], and Lieutenant-Colonel G.R. Geary, MC. Following the service, the remains were taken to St. James' Cemetery, Parliament Street, where they were interred in the same grave as Durie's father (Block 8, Plot 136). Mrs. Durie had a Cross of Sacrifice mounted over the grave similar to those found in Commonwealth War Graves Commission's cemeteries. Beside the main gravestone is a flat slab on which is engraved details of Captain Durie's military life. When she died eight years later, Mrs. Durie's body was buried in the same grave to lie beside her husband and son.

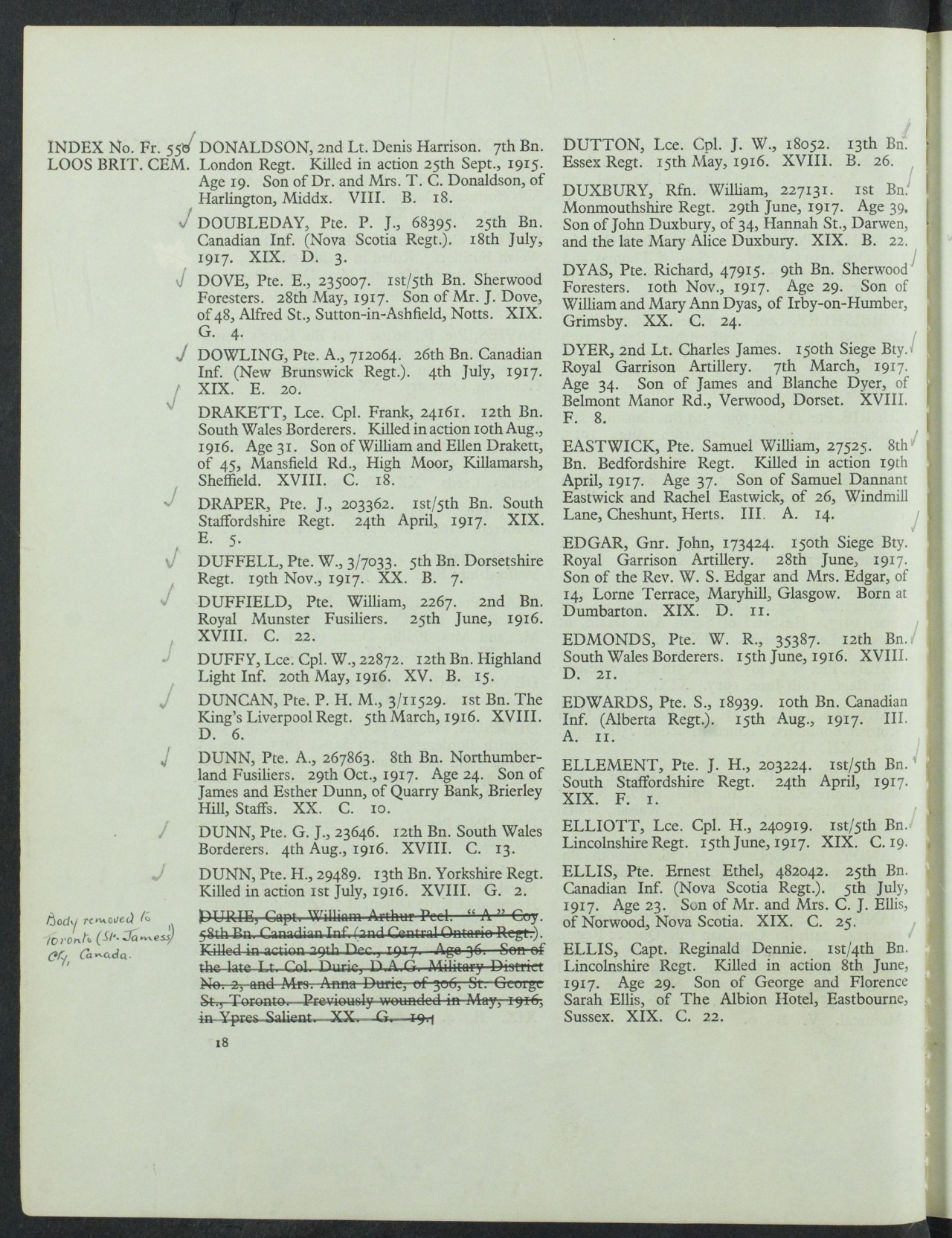

Footnote: Steve Binks has done a bit of detective work and has unearthed the original cemetery register from the CWGC website. It has been amended at some stage to indicate that Captain Durie had been removed to Toronto – see below.

From Pam Hall – an extract from Part 18 of the magazine “Twenty Years After”

Not a war history but – a book of memories

From The Editor to his Readers…

A Vintage Year

The second year of the War, 1915, produced a vintage crop of trench novelties. The Army had not at that time settled down comfortably with the excellent and fool-proof Mills’ bomb. Inventors however, were everywhere busy and the results of their industry gave pleasure and not a few thrills to members of bombing classes at home and overseas.

It so happened that for some months at the end of 1915 and early 1916, I was home from the front, and being temporarily attached to a training battalion, had excellent opportunities for the inspection of all that was going on in the bombing schools. Our own particular expert was a youngster of some eighteen summers, who at the outbreak of war was about to begin his second year in the medical schools of Edinburgh University. That boy, sadly now long since dead, had the hands, sensitive and delicate, of a surgeon, and he took to bombs and the handling of high explosives as some take to snake-charming.

All the skill and enthusiasm that in other circumstances would in all probability have carried him to Harley Street, he now devoted to his beloved grenades! Such was his knowledge that, until his death as the result of exposure on the Western Front, neither he nor any of the countless men he trained ever met with any mishap.

He built up a unique collection of grenades of all types. These, some of which were almost museum pieces, he kept for lectures. All his demonstration and practical work he carried out with jam-tin bombs, at the manufacture of which he was adept.

Sleeping on a Volcano

At an early stage of his career, supplies being hard to come by, he became friends with the manager of a coal-pit, situated some ten miles from the barracks. Once or twice a week he would set off on his bicycle, pedal his ten miles there and back, loaded on the return journey with two haversacks filled with sticks of gelignite. For a day or so after each journey all his spare time would be spent in a hut filling his tins with gelignite and quantities of metal spare parts. He kept his filled bombs in a shed until required for use, when he would fix detonators and fuses.

Nobody of course, objected to the bomb store, but much despondency was apparent in the officers’ quarters when it became known that the bombing expert insisted on keeping his store of demonstration grenades, plus all the unexpired portion of his gelignite… under his camp bed. This alarm was justifiable when it is understood that, not infrequently, there would be enough gelignite under that bed, to wreck the whole wing!!

From Classic Times

Not the least interesting among the novelties of 1915 were certain engines for hurling grenades from one trench to another. Of these I recall the West Spring Gun and the Trench Catapult. Both devices were modelled on the lines of siege weapons from ancient times. I cannot recall the fate of those grenade throwers and can only say that when I returned to the front in 1916 they were not in evidence, so far as I could see.

The West Spring Gun was a heavy and powerful thrower. Consisting of a throwing arm, with a shoe for the grenade, mounted on a heavy base plate and impelled by strong springs, it may have been that this engine was too cumbersome for trench use…. or, that it was too sensitive to mud and water! The Trench Catapult on the other hand, was light and readily portable. It was a strong rubber catapult mounted on a wooden frame. Under training battalion conditions, where the catapult could be properly housed and only brought out for use, its performances were excellent. The bombing instructor referred to earlier on this page and any of his squad could, at various ranges, drop five bombs out of six on the target. Perhaps however, conditions at the front were such that the catapult deteriorated and lost accuracy.

It was the crowning virtue of the Mills’ grenade that no amount of bad weather or careless handling seemed to destroy its efficiency.

Dangerous Souvenirs

This question of grenades and shells and their works is worthy of just a few words. A little knowledge of the subject is useful to others besides ex-servicemen, if only it helps them to recognise that a very undesirable type of war “souvenir” which I have reason to believe still lurks in many a home up and down the country…. is the live projectile!

(and possibly/probably STILL lurks eighty years on! Pam)

Book review

Years of Combat

William Sholto Douglas

Collins, London, 1963

I read this book as part of my research into the life and times of Gordon Shephard, who was the most senior RFC or RAF officer killed in WWI (and indeed the book does have information on him).

William Sholto Douglas was in the RFC from the early days of WWI. Subsequently, he served in various senior command posts in the RAF in WWII starting off as deputy chief of the air staff, and was commander of the British zone in occupied Germany after WWII. He became the first Baron Douglas of Kirtleside in 1948 after his retirement from the RAF.

For all his Scottish ancestry, Sholto Douglas was the product of very upper class English education. This rather posh background does come across in writing style of the book, and needs to be put up with in order to get to the very interesting personal account of the early days of the RFC, and eventually the RAF. Incidentally, in WWII his upper class disdain for Americans stopped him from being given a senior appointment in a theatre where the supreme commander was American.

In WWI, he started off as a 2nd lieutenant in the RFA and transferred to the RFC in January 1915, after a disagreement with his commanding officer. He became operational on the Western Front in August 1915, starting off as an air observer. Throughout the war, the bulk of the RFC’s work was air reconnaissance and artillery spotting, even though it is the fighter pilots who became famous. Later on in the war, air attacks on ground targets were more feasible but the weapons loads of the planes were a few pounds.

The main hazard to life and limb in the early days of WWI was the planes themselves. They were very fragile and had to be handled with extreme care. A key issue until late in the war was the low power of the engines available. So, the Farman plane took an hour and a half to reach 4000 feet, but on other days would not even reach that altitude. (It was a “pusher” with the propeller at the rear.) Later on, the radial engines of planes such as the Sopwith 1 ½ strutter and the V12 of the Bristol Fighter were major improvements, along with the ability to fire forwards through the propeller.

The planes themselves were made of wood with fabric covering which was “doped”, that is treated with a lacquer solution to stiffen the cloth. (In fact, it was nitrocellulose which would not have helped in the event of a fire). If that had not been properly applied, the cloth could flap and tear, probably causing an accident. There were no flaps at the edge of the wings – instead the whole wing was twisted, known as wing warping. The wooden frame could break in aerial manoeuvres, again almost certainly causing a crash. Sholto Douglas recalls seeing Mick Mannock managing to land a Nieuport after the lower wing had broken away – a tribute to Mannock’s considerable talent. The crash which killed Gordon Shephard in 1918 seems to have been another instance of the plane breaking up in the air, but this time with fatal results.

Sholto Douglas recalls his encounters with Immelman, Boelcke, von Richthofen and Goering. Indeed, much later he read Boelcke’s account of an encounter that Sholto Douglas had with him and Immelmann in December 1915. Boelcke believed that they had killed Sholto Douglas’ observer, Child, but in fact he had been thrown about so much in the encounter that he was thrown over in the aircraft and was violently sick, vomiting over Sholto Douglas in the rear seat! The RFC aircraft did not have any forward firing guns until 1916, apart from inefficient “pusher” configuration planes. With Douglas’ planes of this era, the observer sat in the front seat and the pilot in the rear. The observer had to fire his Lewis gun backwards, over the pilot’s head, which was useful if they were being pursued but not otherwise. There were also no parachutes, as supposedly a reliable parachute had not yet been invented. This was a lie from the high command, as Sholto Douglas recalls with righteous indignation, as parachutes were available well before WWI. The “idea” was to stop crews recklessly abandoning their aircraft.

As well as being vomited over by one’s colleagues, the crew would get a face full of flies, especially at low altitude, and be dosed with oil vapour from the engine. The engine oil of the era was castor oil, so there could be unfortunate effects on the digestive system of the crew.

In the book, the author recalls the somewhat bizarre early careers of those who became leaders of the RAF. Trenchard was serving as a Lt Col in the Royal Scots Fusiliers and learnt to fly in his late 30s. Arthur Harris was a bugler in the 1st Rhodesian Regiment and served the first few months of the war in German West Africa. Arthur Tedder was in the colonial civil service in Fiji. Peter Portal started the war as a motorcycle despatch rider. Keith Park was a Kiwi who served in Gallipoli as an NCO. Hugh Dowding was a Scot and had been a captain in the RGA who had learned to fly in 1913 at the age of 31. He transferred to the RFC on the outbreak of WWI.

After the end of WWI, Sholto Douglas left the RAF and worked for Handley Page as a test pilot. He was offered a financial job through family contacts by the famous banker JP Morgan but a chance encounter with “Boom” Trenchard saw him return to the RAF in 1920.

An interesting side issue is that Sholto Douglas’ father was Director of the National Gallery in Dublin during WWI, where Sholto Douglas visited him. In the summer of 1917, he was asked to reconnoitre appropriate sites for airfields in Ireland, and claims the credit for the creation of Aldergrove outside Belfast and Baldonnell near Dublin, both still in use today. He recalls landing his plane in Phoenix Park in Dublin outside what is now the president’s residence, as of course there was no airfield yet in use. He recounts that, if he turned up to recce a site by car in his military uniform, the “corner boys” would jeer and throw stones, but if he arrived by plane and landed in a field, everybody was ecstatically happy to see him! Clearly, it pays to arrive in style.

After retiring from the RAF, Sholto Douglas became chairman of British Airways, as we know it today, in 1949. He died in 1969.

This book is out of print, so if you want to read it you will have to track it down in a secondhand bookshop, online or otherwise. It is certainly an interesting account of the WWI era in the air.