Paramilitaries

They existed in Central and Eastern Europe, and in the UK. (The British used various paramilitaries in Ireland, mainly as they were cheaper than police or troops, and Britain was short of both). Cheapness is a key feature of paramilitary forces.

Paramilitary forces are a feature of political power vacuums. In the era in question, these forces existed both in contested border regions and inside the state. They were, in different guises, a way round treaty restrictions for governments, and also a feature of the weakness of the forces under direct control of those governments which did not have the military power to quash them.

A key issue with paramilitaries is - who controls them? A major problem was that they were, to a greater or lesser extent, out of control. Massacres of innocent civilians were, and are, a common feature of paramilitary activity. One way to control paramilitaries is to be even more brutal than they were, an obvious example of which is Hitler's "Night of the Long Knives" - see below.

One historian uses the term “warlordism” to describe paramilitary activities, that is whoever has the military might controls everything.

In these quasi civil war situations, both groups and individuals switched sides when it suited them.

Let us look at the Finnish civil war as an example of the use of paramilitary forces.

In 31 December 1917, Finland obtained its independence from Russia, somewhat as a side effect of the Russian October revolution (which in fact happened in November 1917, as the Russians still used the old Julian calendar.) Finland had been a semi-autonomous region in Tsarist Russia.

On 27 January 1918, “red” Finns seized Helsinki. The Russian Bolshevik army helped “red” Finns in Karelia (which today is astride the SW part of the Finnish-Russian border). The opposing “white” army was a mix of so-called civil guards, army conscripts, Swedish volunteers, and the German Baltic army division under von der Goltz. The German army took Helsinki on 13 April 1918. On 16 May 1918, white victory was declared. In the six months of the civil war, there were 38,000 dead, out of population of 3.2 million, ie more than 1% of the entire population was killed, partly in the “white terror” when the anti-Bolshevik forces murdered supposed Bolsheviks. About 10,000 of the 38,000 dead were combat deaths, the rest being massacres and deaths in prison camps. Like many civil wars, the Finnish civil war is not discussed in Finland today.

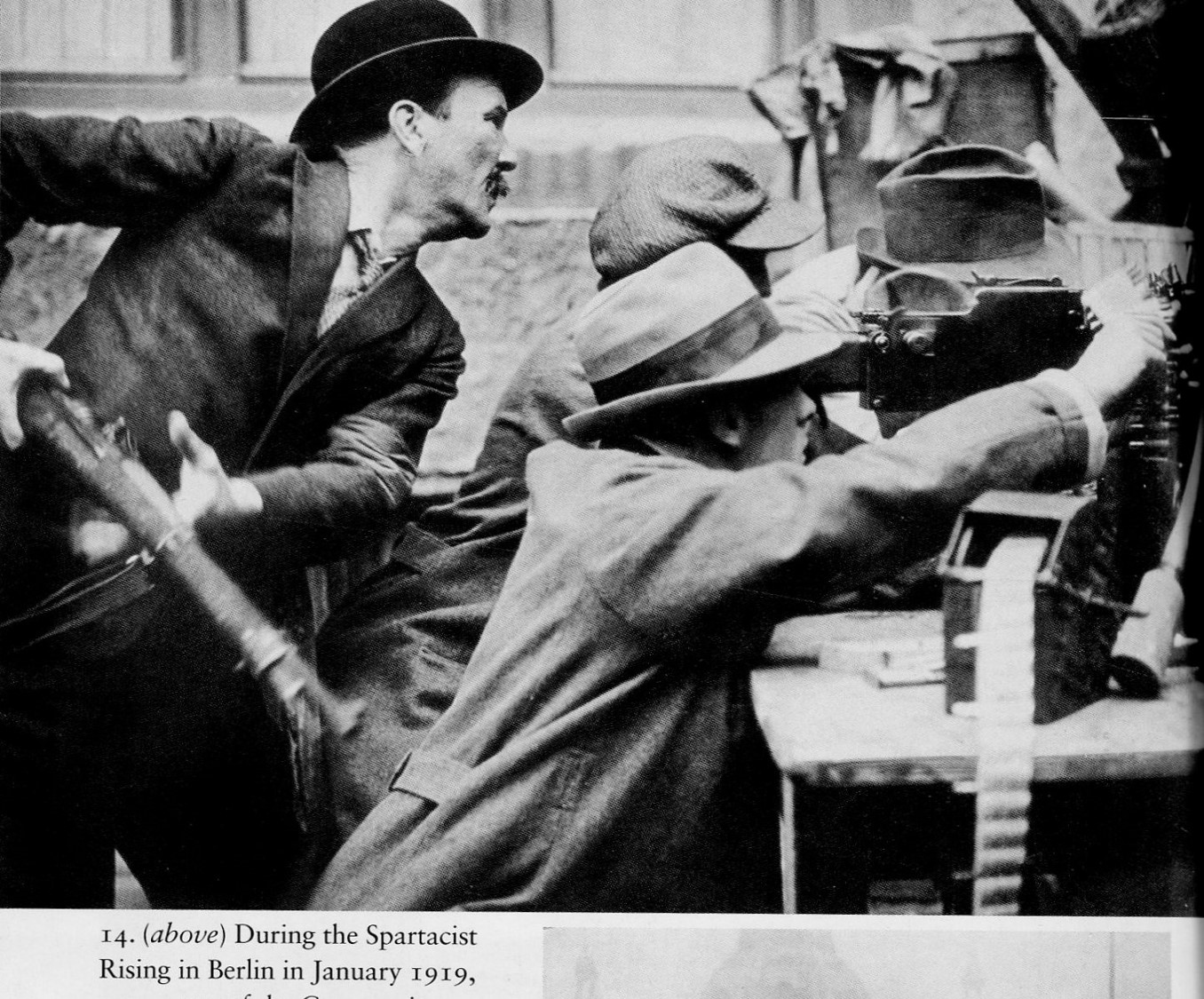

Perhaps the most notorious paramilitary force was the German Freicorps, but they were far from being the only German paramilitaries. There was “surplus” military personnel available, as the size of army was restricted, so the government of the day used the Freicorps but many of their “adventures” got out of hand, which brings us back to the question of how do you control paramilitaries. The Freicorps was the semi-official bulwark against communists. In Germany at the end of WWI, there was political chaos and street battles. See the photos from the Imperial War Museum collection of the fighting in Berlin and Munich.

As well as the Freicorps, there was the Einwohnerwehren (Home Guard). Both were dissolved by the government in the end. However, there were political paramilitaries belonging to the political parties:

- Sturmabteilung (SA) – National Socialist (Nazi)

- Rote Front – Communists

- Reichbanner Swarz-Rot-Gold – Socialists

- Stahlhelm - Conservatives

The SA gives an example of the uncontrollable nature of paramilitaries. When the Nazis came to power in 1934, the leadership of the SA was murdered by the Nazis in the Night of the Long Knives, which was actually a period of several days, as they were too much of a loose cannon and needed to be brought under control.

Freicorps guarding communist prisoners, Munich 1919 (Imperial War Museum)

The Freicorps suppressed the (communist) Munich republic in 1919 and were involved in the street battles with the Sparticists (communists) also in 1919. They murdered the communist politicians Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, and the centre-party leader Mattias Erzberger, who had signed the Versailles Treaty. The Freicorps took part in the Kapp Putsch in 1920, after which they and the Einwohnerwehren were supposedly disbanded. However, the Freicorps operated in the Baltics and were involved in anti-communist campaigns and purges against communist elements. Freicorps members were involved in the 1923 Munich beer-hall putsch, lead by Adolf Hitler (who, incidentally, started off as a communist). They became anti-left street fighters and some were involved with the Nazis.

Sparticist (communist) uprising, Berlin 1919: note the Maxim machine gun (Robert Gerwarth, The Vanquished)

There are more photos of civil unrest below and give some idea of the seriousness of the fighting in Berlin, with some closer to home further down the page.

Berlin 1919 – Freicorps (IWM)

Berlin 1919 – German army at Belle Alliance Platz (IWM)

Berlin 1919 – Government troops: note the soldier has a potato-masher grenade and an Iron Cross ribbon (IWM)

Tank in Capel Street, Dublin. Tanks were also deployed to Glasgow but were not on the streets

North Longford “flying column” of IRA, 1919-1921

Auxies in Dublin, March 1921. (Auxiliary Divn RIC, often incorrectly described as Black and Tans)

Ulster Special Constabulary C Specials – unpaid and ununiformed, just issued with guns. Albertbridge Road area of East Belfast. They were disbanded after 6 months. (Belfast’s Holy War, Alan F Parkinson)

The British Army after WWI – where were they?

There were major political arguments inside government about the size and deployment of the army, which boiled down to money! The UK was having to repay war loans to the US and finance pensions to ex-soldiers and their families at a time when there was a major economic slump. There were continual battles in Whitehall between the Treasury, which said that expenditure on the services needed to be reduced, and Sir Henry Wilson, CIGS (Chief of the Imperial General Staff), who was demanding either more resources or reduced commitments. In fact, politicians of whom Lord Curzon was the worst, were dreaming up colonial adventures in addition to the existing army commitments in Europe and beyond. Various “solutions” for the manpower crisis were discussed, notably using the Indian army in the Middle East and using African troops. These troops were cheaper than using white troops. Ultimately, there were major objections from the colonial authorities, including financial ones. Paramilitaries were another cheap route. They were used in Ireland, as the Black and Tans (RIC Special Reserve) and the Auxies (Auxiliary Division RIC), and the recruitment of local forces such as the gendarmerie in Mesopotamia –see Lt Col Barlow’s story below. The Auxies served in Palestine after the truce was agreed in Ireland in July 1921. A historian in Israel has been tracking their activities there in the years following 1921.

Army numbers in 1914 were 250,000 soldiers including 75,000 in India. The policy since the Indian mutiny had ben to retain a sizeable force of white soldiers in India. In the post-war period, this policy had to be greatly watered down as there were demands on army manpower in many theatres.

In November 1918, there were some 3,660,000 soldiers in the British forces. By 1919, this had been reduced to 800,000. By March 1920, the conscripts had all been demobbed, so that by November 1920 the army strength was 370,000. This was little more than the pre-war strength but there were now increased demands on the army, notably to occupy new territory as a result of the post-war treaties.

As we have seen earlier, the “old hands” of WWI were anxious to go home and they were replaced by new recruits whose training was often delayed and incomplete.

What was happening post-WWI was interfering in other people’s countries. One view of this is:

“The habit of interfering with other people’s business and making what is euphoniously called ‘peace’, is like ‘buggery’ – once you take to it you cannot stop”

General Sir Philip Chetwoode, quoted by Gen Sir Henry Wilson, in a letter of 11 August 1921 to General Sir Charles Sackville-West

An example of British army deployments - Mesopotamia

Let us look at the sad case of Lt Col Joseph Edward Barlow. He was born at Heswall on the Wirral, near Chester. He joined the Canadian army in Ottawa in August 1914, transferred to the British army in 1915 and was commissioned. He finished the war as a Lt Colonel with a DSO and an MC. He continued in the army and was CO of the 22nd battalion of the Manchesters in Egypt when he was recruited to join the Indian Office as a political officer in Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq. The British did not have sufficient manpower to put sufficient troops into Mesopotamia, so they were recruiting a local gendarmerie to fill the gap. There was a revolt in June 1920 and Lt Col Barlow was killed at the town of Tel Afar some 40 miles west of Mosul, along with the rest of the small detachment there. He is buried in Baghdad. The telegram informing the Indian Office in London of these events is below. It is worth noting that it was copied to Simla (where the Raj retreated to in the summer), Constantinople, and Tehran, all of which had a substantial British presence. History does repeat itself – British troops training the Iraqi police in 1920!

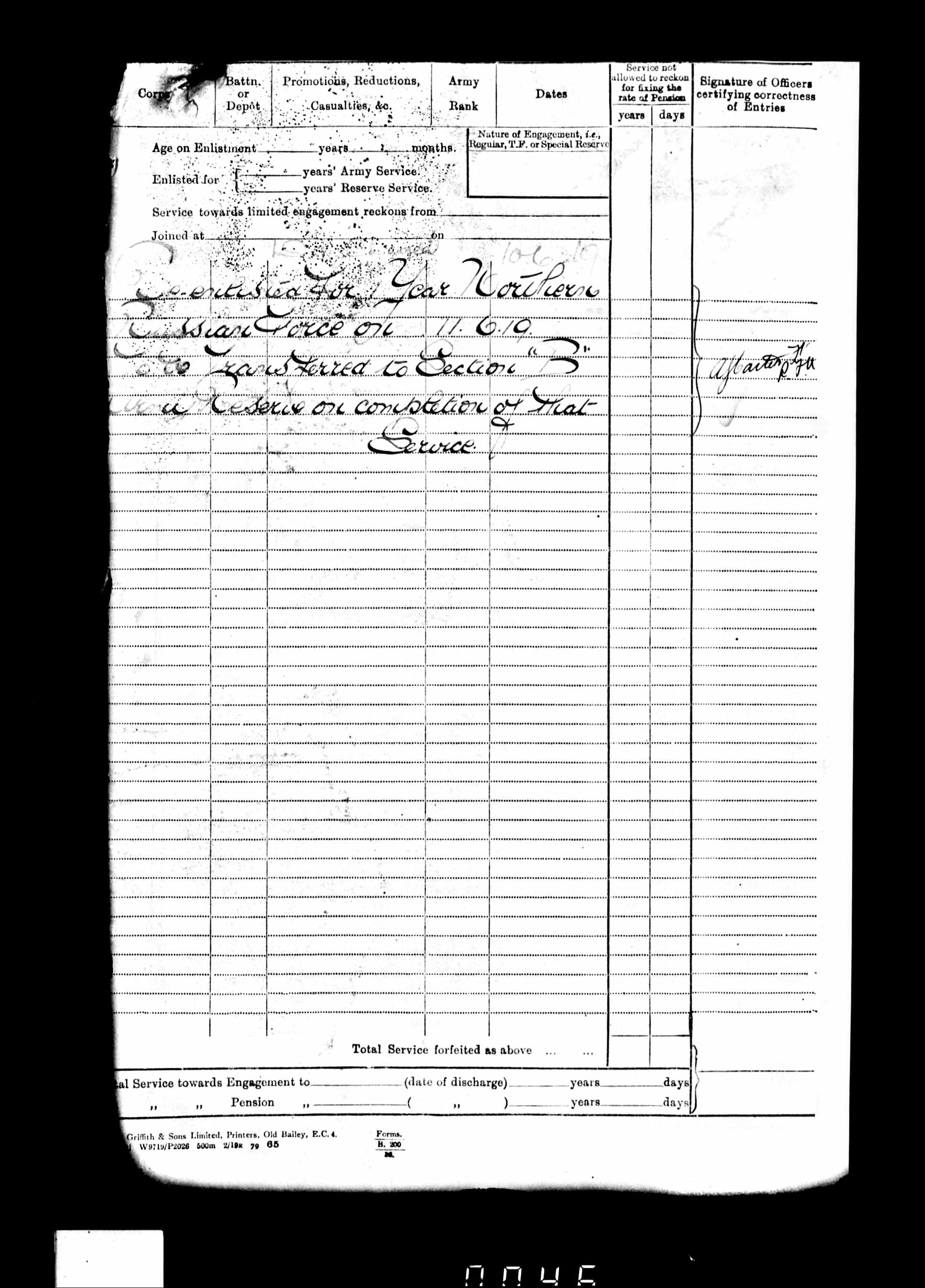

Another example – Gunner Lawrence Murphy, RFA

Gunner Murphy was from Fermoy in County Cork, joined the Royal Field Artillery in 1912 and served throughout WWI. He was demobbed in February 1919. But then his record has the sheet below. He signed up in June 1919 for the British Northern Russia force. So, here is an example of an ordinary soldier being propelled into one of the post-WWI conflicts. We will look at the British dalliance in Russia shortly.

British adventures in Russia

This is perhaps the outstanding example of ill-fated colonial adventurism.

Even before the end of WWI, when all was desperate on the Western Front, the government was playing around in Russia. In April 1918, troops sent to Arkhangelsk and Murmansk in Northern Russia. This started as 150 soldiers and marines and ended up as 18,000. The force was eventually withdrawn in October 1919. To quote Sir Henry Wilson CIGS:

Once a military force is involved in operations on land, it is almost impossible to limit the magnitude of its commitments.

There was also involvement, as we shall see, in the Caucuses. To quote the Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon:

It is a remarkable fact that though…we were the saviour of the situation, we appeared to be disliked by all parties.

This “dislike” is perhaps due to the fact that the British had no business being there. The region is today Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan (which, incidentally is not only three different languages but three different alphabets, none of which is European Latin or Russian Cyrillic).

Areas of British interference in Russia, marked by in red:

The Baltic, Murmansk and Archangel, Siberia, the Urals, the Caucuses, and (off the map) the Black Sea

Curzon had been Viceroy of India and was obsessed by India. He had a vision of a buffer zone to the north and west of India to protect it. However, to quote his fellow member of the government Lord Robert Cecil:

A certain section of the government consider that the Caucuses is one of the gates to India, treating, I suppose, the Caspian Sea, Transcaucasia and Afghanistan as a kind of private avenue leading to the actual Indian frontier

What conceivable hostile power is likely to attempt to invade India at this stage of the world’s history?

He goes on to say that, if it is the Russians, they are having a civil war at the moment, so have other matters on their mind. In short, Curzon’s idea was utterly impractical and unnecessary. One of the suggestions was a “defence line” stretching from Constantinople in Turkey through to Turkmenistan. The minor matter of who was going to man this line of several thousand miles never seems to have arisen in Curzon’s mind.

The fourth and last part of this article is here