The Dragon’s Voice

In this issue, we have an article on the Polish contingent on the Western Front, yes there was one, and two book reviews. As ever, we owe many thanks to Jim Morris for allowing us to use his WWI day by day material on the Facebook page. The next issue of this newsletter will be February 2018, as we have no formal meetings of the branch until then, after next Saturday.

Trevor

The Programme for 2017

Nov 4th : Jane Austin: News from Nowhere: a talk based on her recently-published book about family letters sent from the Western Front back to Bangor

Dec 2nd : Branch Social

Last Month’s Talk

John Stanyard came to talk to us about the Salvation Army in WWI. In fact, an early decision was taken by the leadership that the Army should remain neutral, not least as it had a presence in many of the participating countries. A key role was the welfare of the troops, of course. Part of this was catering and, to that end, we have a copy of the recipe for doughnuts made by the American Salvation Army young ladies and served to the American contingent to make them feel not too far removed from their homeland. (See below).

The Polish “Blue Army”

Trevor Adams

I was fortunate enough to be at two talks this year given by Marcin Hasik on the Poles in WWI. You will gather from his name that he is Polish, and he is an historian. The story of the Poles in WWI is complex. A key episode was the Blue Army which fought on the Western Front in 1917-1918, and was the subject of Marcin’s second talk. It is “blue” because these Poles were a part of the French army and wore the French uniform but with the important variation of the “square” cap still worn by the Polish forces today. What follows below is a brief account of Marcin's talk at the Dublin WFA (and Ian Chambers' photos!)

For more than a hundred years before WWI, there was no Poland. The territory which we know as Poland in recent times was in 1914 subsumed into Austro-Hungary, Germany and the Russian Empire. Some Poles had therefore emigrated to other lands, including to France which had more than 20,000 Poles by 1914. Historically, upper class Poles had gone to France in the 19th century, eg the composer Frederick Chopin.

Of the 25.6 million Poles in 1914, some 2.6 million had emigrated to the United States, as indeed had many other Europeans in the pre-WWI period. There were also Polish communities in Australia and South America.

At the outbreak of WWI, about 1,000 of the French Poles joined the French Foreign Legion, as did some expatriate Czechs. At the Battle of the Marne in 1914, a large number of Poles in the German army defected to the French side. (In WWI, there were Poles as well in the Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian armies – I said it was complex.)

In May 1915, the Bayonne company of Poles was formed as part of the French army’s Marocaine Division, and were at an early engagement at Vimy, where there is a monument near the car park for the Canadian memorial there.

After June 1916, “foreign” citizens of enemy countries could not be in the French Foreign Legion, which included the Poles, though they could be in the French army.

Right: standard of the Bayonne company, complete with bullet holes

Moving now to consider the US situation, there were Polish self-help organisations there including the Falcon Field Squads, which were military training units. They had also existed in Galicia, part of  Austro-Hungary, but were restricted there in what they could do. The Falcon Field Squads were similar to, in Ireland, the quasi-military Ulster Volunteer Force and the Irish Volunteers in that they had access to weapons and training. (The Falcons still exist in the US today, as Polish clubs, typically around the traditional centres of Polish immigration in Philadelphia and Chicago). The transformation of the Falcon Field Squads was brought about by the entry into WWI of the US in April 1917. Paderewski called on the US Congress to allow a Polish unit to be raised, and called on Poles in the US to volunteer to go to Europe. At this time, President Woodrow Wilson called for an independent Poland.

Austro-Hungary, but were restricted there in what they could do. The Falcon Field Squads were similar to, in Ireland, the quasi-military Ulster Volunteer Force and the Irish Volunteers in that they had access to weapons and training. (The Falcons still exist in the US today, as Polish clubs, typically around the traditional centres of Polish immigration in Philadelphia and Chicago). The transformation of the Falcon Field Squads was brought about by the entry into WWI of the US in April 1917. Paderewski called on the US Congress to allow a Polish unit to be raised, and called on Poles in the US to volunteer to go to Europe. At this time, President Woodrow Wilson called for an independent Poland.

Elsewhere in the world, the Russian revolutions had taken place in March and November 1917 (ie the “October” revolution actually took place in November, as the Russians still used the old calendar). Paderewski saw Russia as an important ally for the independence of Poland, so the revolutions were seen as a positive step toward an independent Poland, rightly or wrongly.

Various figures of the era favoured the formation of the Blue Army, such as the Polish statesman Roman Dmowski who was an important mover in late 19th and early 20th century peaceful agitation for independence. (Unfortunately, his National Democracy movement lurched to right-wing nationalism after Poland’s independence.)

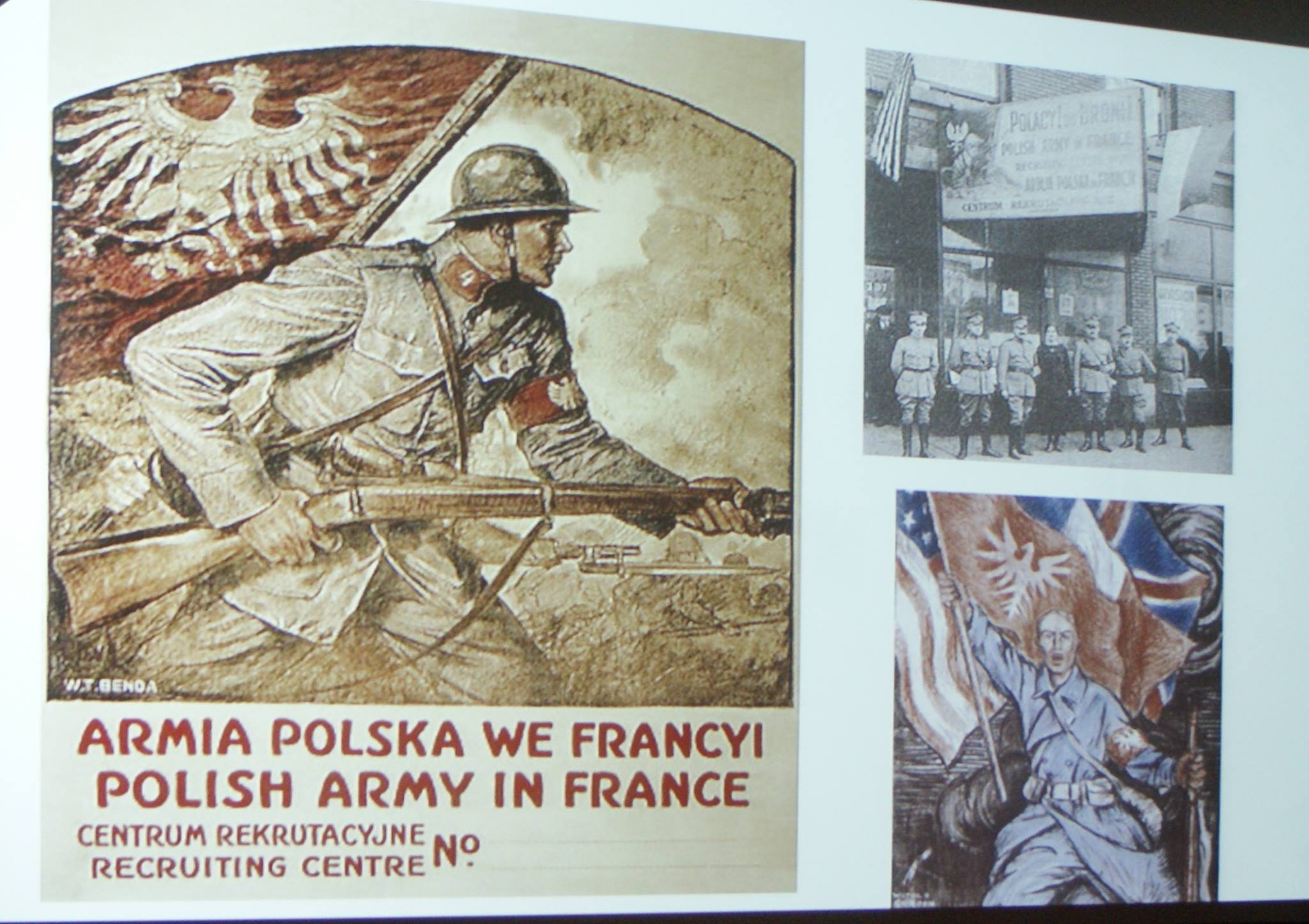

A famous figure from Poland’s past, Taduez Kosciusko, a hero of the independence war in the 1790s and who fought in the American War of Independence, was used as a recruiting figure for the Blue Army – see the photo left.

In France in 1917, the government called for the formation of a Polish army, and a Polish National Committee was also formed (as there was, of course, no Polish government as such). Existing Polish

soldiers in the French army could transfer to the Blue Army, ie the US contingent.

Right: poster used in the US to recruit for the Blue Army

In the US, only non-US citizens could join the Blue Army. Some 20,000 men were recruited and sent to France. The first contingent arrived there in December 1917. They fought with the French in Champagne in the summer of 1918. General Haller was appointed by the Polish National Committee as the commander of the Blue Army in October 1918, and it is said that it was he who promoted the name “Blue Army”. A major attack was planned for late 1918 but was cancelled because of the ceasefire.

Haller had been in the Austro-Hungarian army some time before WWI and had fought with the Polish contingent in the Austro-Hungarian army against the Russians. After the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, he had fought the Germans as he regarded the treaty as a disaster, resulting in the Battle of Kaniow, in the Ukraine between the Poles and the Germans, after which the Polish Legions were interned but Haller escaped via Siberia and ultimately to France. The Blue Army is sometimes referred to as “Haller’s Army”. He was a key figure in the post-WWI wars fought by Poland. He eventually died in exile in the UK in 1960.

Below: a Polish army “square” cap

After the Armistice in 1918, the Polish National Committee wanted the Blue Army to be transferred to Poland to help to secure its independence. This was only agreed to by the French after six months. So, in 1919, 192 trains transferred the Blue Army to Poland. By that stage, it comprised 70,000 soldiers, 120 tanks, 98 planes and some artillery. The Blue Army was de facto disbanded in late 1919 and became part of the Polish army. Some 10,000 to 12,000 soldiers returned to the US. In the

1919-1920 period, Poland fought wars against the Ukraine, Soviet Russia and Lithuania. The borders were finally settled by the League of Nations in 1921. Incidentally, the Polish unknown soldier is from the war with Ukraine, not WWI. There is a Polish memorial on the Western Front at Neuville St Vaast, near Vimy.

A footnote to all this is that the grandfather of German PM Angela Merkel fought in the Blue Army. He was ethnically Polish and was from what is today Poznan in Poland but was part of Imperial Germany in 1914. (Merkel is her married name. Her maiden name is Kasner which is the Germanised version of the original Polish “Kazmierczak”.)

Well, it is quite a complicated and little known chapter of WWI!

Book Reviews

Greenmantle

by John Buchan

Some of you may remember Paul Knight’s talk on Mesopotamia. In that, he mentioned the fall to the Russians of the fortified Ottoman city of Erzerum, in February 1916. Questions remain over the reasons for the sudden Ottoman collapse, and Paul commented that Buchan’s explanation in Greenmantle could well be accurate. I decided it was time to re-read that classic.

My copy is from Oxford University Press’s World’s Classics series with a fascinating introduction and explanatory notes by Kate Macdonald. ISBN 0-19-282953-X.

First, we should say a little about the author, in order to put the book in context. Buchan was in charge of Land Settlement during the British Government’s drive to resettle South Africa after the Boer War, but later returned to England. At the start of the First World War, he became involved in intelligence work. In 1915 he was the Times special correspondent on the Western Front and from late 1915 he worked for the Foreign Office and War Office. He was highly regarded for his knowledge and understanding of the wide geographical nature of the war and the interplay with internal politics in the nations involved. Between 1915 and 1919, he wrote the 24 volumes of Nelson’s History of the War. He was thus in a position to know something of the opinions and concerns of those in high places when he wrote Greenmantle in 1916, just after the genuine events that are the backdrop to his tale.

The story is a further adventure for Richard Hannay, the hero of The Thirty-Nine Steps. As he is convalescing after injuries received in the Battle of Loos, he is called to the Foreign Office and asked to take on an even more dangerous assignment that will see him cross Germany and, by circuitous routes, arrive in Constantinople. From there, he and his companions make their way to Erzerum as it is being bombarded by the Russians. After many adventures and escaping death by a hairsbreadth more than once, they foil the German plot, get information on the weak point of the Ottoman defence to the Russians and ride into Erzerum with the victorious Cossack cavalry. It is a rattling good adventure story and the characters so well drawn and the tale so expertly told that it seems almost believable. It is worth reading for the adventure story alone.

It is the context, however, that gives the historical interest. The plot which Hannay and his accomplices uncover is a German attempt to manipulate a dying Islamic prophet to inspire and inflame the jihad which had been proclaimed against the British and their allies. At Hannay’s initial meeting at the Foreign Office, it is clear that there is serious concern that the call to jihad would be heeded throughout the Moslem world and it is likely that this accurately reflects Foreign Office opinion in 1915/16. It is more questionable whether there was any basis of fact to support the idea of a German conspiracy to use the prophet Greenmantle, but Buchan was friends with both Aubrey Herbert and T E Lawrence and it is possible he had heard speculations or rumours to inspire his tale. Buchan’s detailed knowledge of various theatres of war leads to a convincing description of Hannay’s journey through war time Europe and his visit to Constantinople in 1910 allowed him to describe that area with detail and atmosphere. His theory was that the fall of Erzerum was due to information on the distribution of the Ottoman defences being smuggled to the Russian commander so that they attacked and broke through the one pass that was still weakly protected because the troops withdrawn from Gallipoli could not reach Erzerum until March. There is likely to be truth in this. T E Lawrence was working in the Cairo Intelligence Department in 1915 and is thought to have put the Russians in contact with some Arab officers in Erzerum who were secretly opposed to the Ottoman Government. This could have been the real source of the information, rather than Hannay and his friends.

Behind the adventure story, then, this book gives a feel for the genuine attitudes and conditions in both Europe and the Ottoman Empire in 1915/16, and I thoroughly recommend it. One word of ‘health warning’, though. Like other Buchan novels I have read, it contains comments and turns of phrase that to a modern reader are jarringly racist. This casual, unconscious racism is also a historical fact, however, and would have gone unnoticed when the book was written, an indication of how attitudes and standards have changed in the last 100 years. Another historical point is made by the comprehensive Explanatory Notes. Written in 1993, they assume the reader will have little or no knowledge of the First World War. This was probably accurate at that time but hopefully after the publicity given to the centenary of the War, some of those notes would be unnecessary today.

The Riddle of the Sands

by Erskine Childers

Those of you who heard Trevor’s talk on the Easter Rising will know of Erskine Childers as a gun runner for the Irish Nationalist Volunteers. This represented, however, a major conversion from his upbringing. He was born in London, but from age six, after the death of his father, he was brought up in Co Wicklow by relations who were part of the Protestant Ascendency in Ireland. He was educated in England at Haileybury College and Cambridge, and in 1895 became a parliamentary clerk to the House of Commons. During the Second Boer War, he joined the City Imperial Volunteers and spent nine months in South Africa in 1900. At the time of writing The Riddle of the Sands, he still supported the British Empire although now willing to criticise it when he saw the need.

Childers’ first book was unplanned. In the Ranks of the CIV was composed from the long descriptive letters he wrote to his sisters from South Africa. With the help of a friend who ran a publishing house, they edited his letters into a book and had the print proofs ready for his approval when he returned home.

The Riddle of the Sands had a more conventional origin. Started in 1901, it was published in mid-1903. It combines Childers passion for sailing with his conviction that the British navy was not ready to fight the European war which many people believed was coming. Late in the season, the narrator of the story is invited to join an acquaintance on his small yacht in the Baltic. From there, they make their way to the north German coast, and among the inlets and sand banks of the Frisian Islands, they uncover a plan for a German invasion of Great Britain.

Childers was a skilful sailor and had cruised this area several times with his brother. His descriptions of the scenery, the weather, and the intricacies and dangers of sailing there are based on personal experience. These descriptions and the detailed maps make the story easy to follow, even for someone with no knowledge of the Frisian Islands or the technicalities of sailing. The writing style is detailed but very readable and the story line is compelling.

As fascinating as the story itself, however, is the information it gives on attitudes at the turn of the century. The basis for the story is that a major European war was inevitable, that Germany and Britain would be on opposing sides and that both were preparing for this. I was surprised that, more than ten years before the outbreak of the First World War, these seem to have been accepted facts. Equally interesting is the criticism of British naval training and policy, carefully reasoned and explained by one of the main characters. This was clearly Childers’ own opinion and the book proved a very successful way to publicise his views. Winston Churchill is said to have credited the book with influencing the Admiralty decision to establish naval bases in Invergordon, Rosyth, Firth of Forth and Scapa Flow. It also helped ensure Childers’ skills were appropriately used when he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer reserve in 1914. His knowledge of coastal navigation was put to use as a navigation instructor for seaplane pilots. Later in the war he served with a coastal motorboat squadron in the English Channel. In The Riddle of the Sands, one character had explained the need for the navy to set up such squadrons.

Reading this book, I wondered to what extent the Howth gun running represented “fiction become fact” for Childers and his wife and friends. Certainly, the photographs they took of themselves and Mary Spring Rice’s diary of the trip suggest an element of amateurish melodrama. One cannot, however, doubt Childers’ dedication to the cause of Irish independence for which he worked and died after his return from the First World War. (Childers was shot in the Irish Civil War for possession of a gun, which ironically had been a gift from Michael Collins who by this time was on the other side, in charge of the new Irish army.)

Childers also wrote volume five of The Times History of the South African War, two books on cavalry warfare and The Framework of Home Rule and co-authored The HAC in South Africa. It is, however, his novel, The Riddle of the Sands, that has stood the test of time. I recommend this book both for its story and for the insight it gives into the thinking of the time.

Caroline Adams

Both Greenmantle and The Riddle of the Sands will be available for loan at the November meeting.

Footnote

When in Dublin recently helping with the WFA stall at a family history exhibition, I was asked to try to trace any records for a gentleman’s relative who had been in the merchant navy. In fact, we couldn’t find his record but the relative is known had sailed through two world wars and eventually retired to Dublin. He is recalled by the family for having acquired in his travels a monkey, which the public health department eventually removed from his terraced house for being a health hazard, and a parrot which sang “God save the Queen”. Not perhaps the best thing to be singing in 1960s Dublin!