The Dragon’s Voice

Hello and welcome! In this issue, we have articles from Keith and Caroline covering everything from stuffed parrots to training sea lions. As ever, we owe many thanks to Jim Morris for allowing us to use his WWI day by day material on the Facebook page.

I thought I would take the opportunity to mention that the Somme is changing, as Teddy and Phoebe from the Ulster Tower at Thiepval have finally retired after 15 years as the “guardiens”. I am sure we all wish them well.

Trevor

The Programme for 2017

Mar 4th : John Sneddon : Bombay Sappers and Miners at Neuve Chapelle 1914

Apr 9th (the second Saturday): Dr Graham Kemp : How the 10th Cruiser Squadron Won the War

May 6th : Jon Bell : Comparing Medical Services in the Great War with now

Jun 3rd : Stuart Hadaway : RWF and the Battles of Gaza and the Thomas Brothers

July 1st : Colin Walker : Scouts in the Great War

Aug 5th : Steve Erskine: Prison of Conscience - Richmond Prison in the Great War

Sept 2nd : Taff Gillingham : Daddy what did you do in the Khaki Chums: Development of Uniforms and Equipment.

Oct 7th : John Stanyard : Under Two Flags, the Salvation Army in WW1

Nov 4th : Jane Austin: News from Nowhere: a talk based on her recently-published book about family letters sent from the Western Front back to Bangor

Dec 2nd : Branch Social

Last month’s speaker

Our own Bridget Geoghegan came to talk to us about graves and memorials on the eastern side of Anglesey, including in the cemetery on the island in the middle of the Menai straights – Church Island. She showed just how much work is involved in trying to identify WWI graves that are marked with a family headstone. We have some of the information on these local memorials on the website - Anglesey heroes

“Q” Ships:

A mystery VC and a stuffed parrot

Keith Walker

On the 20th July 1917 the “London Gazette” published the following.

Citation reads:-

“To receive the Victoria Cross, Lieut Ronald Neil Stuart DSO, RNR and Sea. William Williams, RNR ON 6224A. Lieutenant Stuart and Seaman Williams were selected by officers and ships company respectively on one of HM Ships to receive the Victoria Cross under Rule 13 of the Royal Warrant dated the 29th January1856”

No other information was released, and so started the mystery of the VC.

(photos right: William Williams during the war and in later life)

“Q” ships also known as “Q” boats or “Special service ships” were heavily armed converted merchant ships. They were designed to lure enemy submarines into making surface attacks. The Germans preferred to attack single small merchant ships with their guns, saving their torpedoes for larger ships. The “Q” vessels were comparatively small ranging in size from 4,000 tons to small sailing ships. They were disguised to look old and poorly maintained. Their outward appearances were indistinguishable from ordinary merchantmen.

The “Q” ships armament usually consisted of one 4inch and two 12 pdr guns. The guns were disguised in a number of ways, behind hinged bulwarks, inside dummy superstructures and deck cargoes. They even concealed the guns in dummy life boats. The ships adopted many elaborate disguises. They changed the name of the ship, and some “Q” ships had as many as five names. The crew used

many ruses to convince the enemy that the vessels were genuine. One of the crew dressed as the captain's “wife”. Other members of the crew came up with other disguises. The cook even had a stuffed parrot in a cage. These men were part of the crew who were nicknamed the “panic party.”

When the “Q” ship was attacked, the ship would allow the submarine to come as close as possible. The crew would then simulate an “abandon ship” routine. The half of the crew who were the “panic party”, including the stuffed parrot, would leave the ship while the other half of the crew would remain hidden on board ready to man the guns. When the captain thought he was in range of the submarine “the closer the better”, he would order the disguise to be dropped and raising the White Ensign (a requirement of international law) he would engage the enemy.

The action that is of most interest to us here in North Wales is when a sailor from Amlwch on Anglesey was awarded the Victoria Cross. The date of the action was 7th June 1917, and the location was off the SW of Ireland in the Atlantic Ocean. The ship was HMS Pargust.

HMS Pargust (photo above right) was a 2817 tons converted collier built in 1907. In 1917, she was requisitioned by the Royal Navy. The ship was converted in the Devonport naval base. She was armed with five guns, that is one 4-inch gun, four 12 pdr guns, and two torpedo tubes, all in concealed mountings. She was also fitted with a gun in plain sight as many merchant ships were defensively armed by that stage of the war. The crew were all volunteers. The captain was Commander Gordon Campbell VC DSO and two bars, Croix de Guerre and Legion d' Honneur (6th January1886 to 3rd July 1953). Commander Campbell had an illustrious career in the navy ending as a Vice Admiral.

One of the crew was the sailor from Amlwch, William Williams. He was born on the 5th October 1890 at Well St, Amlwch Port to Richard and Ann Williams. The 1911 census has the family living at 57 Upper Quay St, Amlwch Port. The census reads:

Head Richard age 40 Seaman

Ann “ 44

William “ 20 Seaman

John “ 18 “ “

Richard “ 16 “ “

Ellen “ 12

Thomas “ 8

Before the war William was a seaman. He served on two 3-masted schooners, the SS Camborne and the SS Meyric, both out of the port of Beaumaris. He had sailed three times to the Rio Grande. William was 6ft tall, strong and very hard working. William was at sea when war was declared on the 4th August 1914 but William knew where his duty was and on the 29th September 1914 he enlisted in the Royal Naval Reserve as a seaman/gunner. His service number was 6224A and within a few days he was mobilised for service on the 2nd October 1914.

I do not know when William volunteered for the “Q” ships, but by 1917 he was serving on board HMS Farnborough which was a 3207 tons converted collier, built in 1904. She was armed with two quick firing 6pdr guns, five 12 pdr guns and one Maxim machine gun. It was on this ship that William received his first gallantry medal on the 17th February 1917 when HMS Farnborough sank U-83 off the south coast of Ireland.

The ship was captained by Commander Gordon Campbell (6th January 1886 to 3rd July 1953) whose order to his officers “should an officer of the watch see a torpedo coming, he is to increase or decrease speed as necessary to ensure hitting “. The ship was duly hit by a torpedo fired by U-83. As the ship sank lower in the water the “Panic party” went over the side, but the gun crews stayed concealed for more than 30 minutes. The submarine finally surfaced to finish off the ship with gunfire. But the gun crews of HMS Farnborough were quicker, opening fire at point blank range they sank the submarine. After the action, HMS Farnborough was beached at Berehaven and the crew returned to barracks at Devonport.

In April 1917, it was announced that Captain Campbell had been awarded the Victoria Cross and Seaman William Williams the Distinguish Service Medal.

The crew all volunteered to join Captain Campbell in his new command HMS Pargust, and it was on this ship that William won his second and highest honour, the Victoria Cross.

On the 7th June 1917, the ship was some 90 miles off the south coast of Ireland when the ship was hit by a torpedo fired by U-29 that blew a hole 30ft across in her side. The explosion had dislodged part of the screen that concealed the starboard gun. William jumped into action and quickly braced himself and taking the full weight of the screen on his back to prevent it falling and giving away the position of the gun. The rest of the crew went into its normal routine of abandoning ship. The “Panic party” went over the side with the poor stuffed parrot. The captain of the U-29 was a very careful man. He circled the ship for some time before he surfaced. All that time, William was perfectly still holding up the screen. When the submarine was in a good position, it must have been a great relief for William when Captain Campbell ordered the gun crews into action. They sank the U-29. William sustained a back injury from which he suffered for the rest of his life.

In July it was gazetted that Lt Ronald Neil Stuart (26th August 1886 to 8th February 1954) and seaman William Williams had been awarded the Victoria Cross. They were selected by ballot of the crew (rule 13 of the Royal Warrant 1856). They received their Victoria Crosses from King George V at Buckingham Palace on the 21st July 1917. Because of the secrecy of the “Q” ships, no public announcements were made. That is one of the reasons why this V.C is such a mystery. The ship HMS Pargust was so badly damaged it was of no further use to the Navy, so it was sold off.

Captain Campbell, together with his crew, was given another command, HMS Dunraven. This ship was a converted merchant ship of 3117 tons built in 1910. It was on this ship that William was awarded his third gallantry medal.

In August 1917, they set sail for the Bay of Biscay and on the 8th August they encountered the German submarine the U-71 on the surface. The submarine engaged them from long range. Captain Campbell tried to entice the submarine closer by making smoke pretending that his engine room had been hit. HMS Dunraven's gun crew manned the gun that was in plain sight. One of the gun crew was William. They fired widely as if in a panic. The rest of the crew went into its normal routine of abandoning ship, so the “Panic party” went over the side with the stuffed parrot. But this time the Captain of U-71 Oberleutnant zur See Reinhold Saltzwedal was not fooled, and he continued firing. One of the German shells hit the detonators of the depth charges, setting the stern of the ship on fire. Then one of the concealed 4 inch guns was hit and was catapulted over the side. All attempt of disguise was now gone. The U-71 circled the ship for over an hour shelling the ship and all this time William and his mates stayed with his gun. With HMS Dunraven sinking the U-71 sailed away. The survivors of this action were picked up by HMS Christopher which tried to tow the Dunraven but she sank two days later on the 10th August 1917.

After the action, William was awarded a bar to his DSM and the Medaille Militaire. Also awarded were Lieutenant Charles George Bonner (29th December 1884 to 7th February 1951) and Petty Officer Ernest Herbert Pitcher (31st December 1888 to 10th February 1946) who both received the Victoria Cross. As a matter of interest, U-71 sank in 1919 when it was making it way to surrender off the coast of Denmark. For his actions on the 8th August 1917 against HMS Dunraven, Oberleutnant Reinhold Saltzwedal received the Order Pour le Merite (a German decoration in spite of the name).

William was given some home leave and the Holyhead Chronicle tried to interview him. He was said to be “at home and indisposed”. What a modest hero. He went on to serve on an auxiliary ship until he was discharged from the navy as medically unfit on the 6th November 1918 with the rank of Leading Seaman.

After the war, William remained on Anglesey. He was employed on the docks at Holyhead. He was one of the founders of the local British Legion and was their standard bearer for some years. He married Elizabeth and had a daughter. Elizabeth died in 1931. Three years latter William married Annie Jones, a widow with two children. William never went back to sea but some time after the war he joined the territorial force. He joined the 6th Btn RWF (TF). He lived at 31 Station Road Holyhead. He died on the 26th October 1965 at the age of 75. He is buried at Amlwch cemetery.

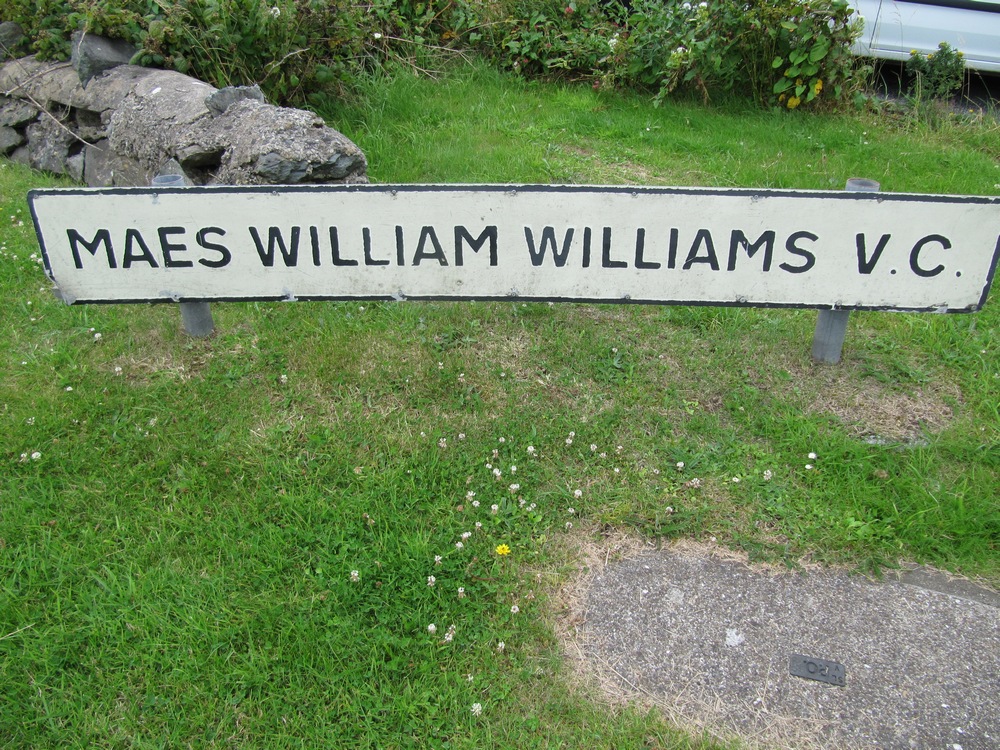

William is commemorated on a number of memorials. Amlwch has named a housing estate after him

His medals are held by the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff.

Between February 1917 and August 1917, Captain Campbell and his crew were awarded:

Five Victoria Crosses

Three Conspicuous Gallantry Medals

Two Distinguished Service Medal, plus 1 Bar

Two Medaille Militare

Two Croix de Guerre

There is no record of the stuffed parrot getting an award but I think it deserves a mention!

As the “Q” ships were so secret there were no public announcements of their activities until after the war had ended. Hence, there is the so-called “mystery” of William's Victoria Cross. There is some confusion with another Victoria Cross winner of the same name, William C Williams (15th September 1880 to 25th April 1915) RNR who was awarded his Victoria Cross on the 25th April 1915 while serving on the HMS River Clyde at the landings at Cape Helles in Gallipoli.

References and acknowledgements

Smoke and Mirrors by Deborah Lake, published Sutton Publishing Ltd, 2006

www.naval-history.net/WW1MedalsBr-VC.htm

Holyhead Maritime Museum

Dog Tag

Keith Walker

At my local history group I was shown this artefact. It was a 1917 French one franc coin made into a personal dog tag bracelet. The airman W.H. Jones Royal Flying Corps s/n 3514 survived the war.

After giving a talk on the nurses in WW1 to another history group, I was approached at the end of the meeting by a lady who said she was a retired nurse and thanked me for recognising the work of the nurses. But what was really interesting was that as a child in the late 1940s she went to France to live with her family, as her father was a supervisor with the CWGC. They spent some time in the area around Thiepval and because of the shortage of accommodation she spent a year to eighteen months living in the Ulster Tower. She said there was no running water or electricity at that time. She visited the tower last year for the commemorations of the battle of the Somme and was shown around the flat by Teddy and Phoebe. She spent sixteen years in France and only came back to

Britain to train as a nurse. She is a very private person so I have not used her name.

First World War Military Sites: Manufacturing and Research and Development

Gwynedd Archaeological Trust

Caroline Adams

In March 2014, Home Front Legacy 1914-1918 was launched by the Council for British Archaeology, Cadw, Historic Scotland and English Heritage. The aim is to record the physical remains of the war on home territory and coordinate this with existing records and archives.

As part of Home Front Legacy, Gwynedd Archaeological Trust has produced two reports so far, with another three still to come. The first, “The Militarised Landscape”, provided some of the information for a previous article in Dragon’s Voice on prison camps in North Wales. The one published in 2016 is “Manufacturing, Research and Development” and makes fascinating reading.

As an archaeological report, it gives a lot of detail on the size and position of remaining buildings and correlates this with contemporary descriptions, plans and photographs, etc to give an impression of what the sites would have looked like 100 years ago. This is not a dry list of buildings, however. They are described in the context of the work that went on there. I had not realised what a big part North Wales had played in the development of longwave radio communication or that there had been a Royal Naval Air Service airship base at what is now Mona Airfield. The airships were used to spot U boats and signal their presence to warships. They also had a limited bombing capacity themselves. Although this was an airship base, farming continued to be carried out on the site, which may explain the one human fatality from flying there. An airship hit a cow on landing and the damage caused it to be blown out to sea where one of the crew drowned. On another occasion, the engine failed on an airship escorting a convoy into Liverpool. It came down on the sea and was towed to shore by a trawler and moored at Llandudno north shore, to the amazement of holiday makers!

Fixed wing aircraft were still a very new development when the war started. Some of the early work on the mathematics of aerodynamics was done by William Ellis Williams at Bangor University. In the pre-war years, he developed a test plane and flew it from the sands at Red Wharf bay.

Most unexpected, however, is the section entitled “Sea Lion Training Base, Glan Llyn”. The threat from U boats was so serious that no suggestion for locating them could be turned down out of hand. There is even a record of an attempt to train seagulls to identify submarine periscopes. A scheme to train sea lions to follow the sound of a submarine went further. After initial trials in Glasgow swimming baths, fifty sea lions were stabled at Glan Llyn and trained in Llyn Tegid, Bala. Two of these progressed to chasing a real submarine in the Solent in May and June 1917, but there were problems tracking them and their performance was not reliable. The hydrophone was more accurate and the project was abandoned.

The section on manufacturing predictably starts with explosive and shell factories but goes on to describe the wide range of locally manufactured goods which contributed to the war effort. Road stone quarried in North Wales was transported to France in large quantities.

North Wales also contributed to feeding and clothing the army and populace. Although most of the woollen mills were in mid Wales, a lot of knitting was done in the North. A workroom of machines for knitting socks was set up in Blaenau Festiniog by an American charity, to help workers who were unemployed due to the changes in industry caused by the war. They were largely staffed by young women who had family commitments that stopped them moving away from home to work in munitions factories and those who were disabled. Older women provided hand knitting done at home. There were similar knitting rooms in Bethesda and Talysarn. Llanrwst had had a leather industry since the 16th century and during the war it produced leather for aviators’ clothing.

Next to the railway at Abergwyngregyn was the Aberfalls margarine factory. Throughout the war, it produced both margarine and soap. Pre-war, their top quality margarine contained butter and egg yolk but by 1918 the recipe looked much less appealing and included formalin as a preservative.

The main report ends with an addendum to their coverage of Frongoch last year, and is followed by comprehensive appendices and a selection of maps and photographs. Altogether it is an impressive piece of research, clearly presented and is well worth a read.

http://www.heneb.co.uk/ww1/reports.html

“Uff” Coastal Battery

Trevor

Well, childminding for the half term holiday does have its compensation. We were in the NE England town of Billingham for the break. Fortunately, Andrew McKay and his chums from the Burnley WFA had mentioned to us that there was the Heugh battery museum at Hartlepool (and Heugh is pronounced “Uff” by the locals). So, we had an expedition there which was interesting for all of us, not least due to the knowledgeable and enthusiastic volunteers in charge.

The battery is on the headland overlooking Hartlepool harbour and the former shipyard. On 16th December 1914, the Hartlepools were attacked by the German High Seas fleet. It was part of a tactic to lure the Royal Navy into an irrational response and pick them off, which in fact was the basic reason for most of the German ventures into the North Sea in WWI.

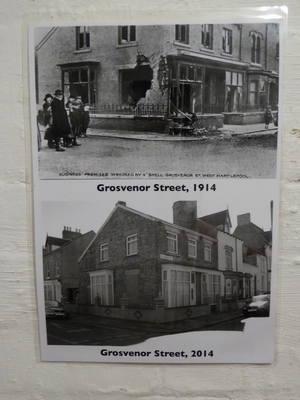

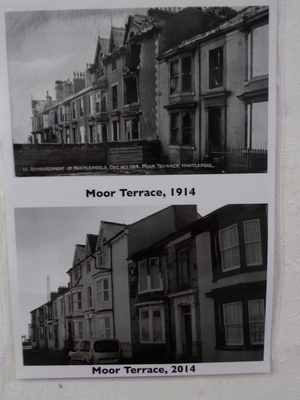

The two guns that are still there in fact date from WWII. The WWI guns would have been bigger as indicated by the recess in the concrete mountings for the guns. However, the magazine and the crew shelters are there and are accessible. The command post with ranging equipment is open and gives a clear view of the approaches to the harbour. The magazine has photos of the damage to the towns from the bombardment and views of the same locations today. There is a wonderful display of small arms, and a knowledgeable volunteer to explain them.

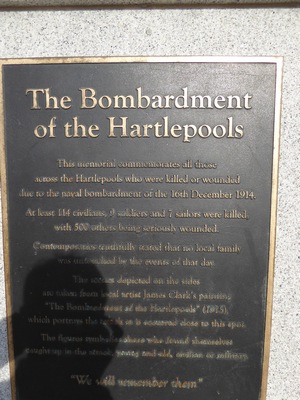

Outside the museum precincts there is a memorial to the attack, which lasted 45 minutes. The casualties were 114 civilians, 9 soldiers and 7 sailors killed with more than 500 wounded. Part of the reason the town was hit so badly was that the German ships were kept reasonably far offshore by the RN and the coastal battery so that their shells had a flat trajectory and tended to go over the battery into the town.

In the centre of Hartlepool, there is a RN museum with the HMS Trincomallee, a sailing ship built in 1807 which is well worth a visit.

There are some photos below of Heugh Battery Museum.

The memorial to those killed and injured, located just outside the museum. (The canon is from the Crimean war)

Above: the command post with ranging apparatus (and granddaughter)

Above: the command post with ranging apparatus (and granddaughter)

Above: View from the door of the command post, out to sea – is the enemy coming?

Above: View from the door of the command post, out to sea – is the enemy coming?

Above: view from the command post of the two guns.

The further away one has a blast wall behind it and a casing.

Above: two of the photos of the damage, “then and now”

Above: two of the photos of the damage, “then and now”

www.nwwfa.org.uk