The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have articles by Terry on the “Black Tom” explosion in New York City, by Caroline on life as a civilian internee in Baghdad in WWI, and a book review on the navy that you never knew existed – the Austro-Hungarian.

For obvious reasons, we have no face to face branch meetings for the foreseeable future, but there is a Zoom meeting (of the Stockport branch) coming up, which anyone can join in, and is on their website – www.landcwfa.org.uk.

The “Black Tom” Explosion

Terry Jackson

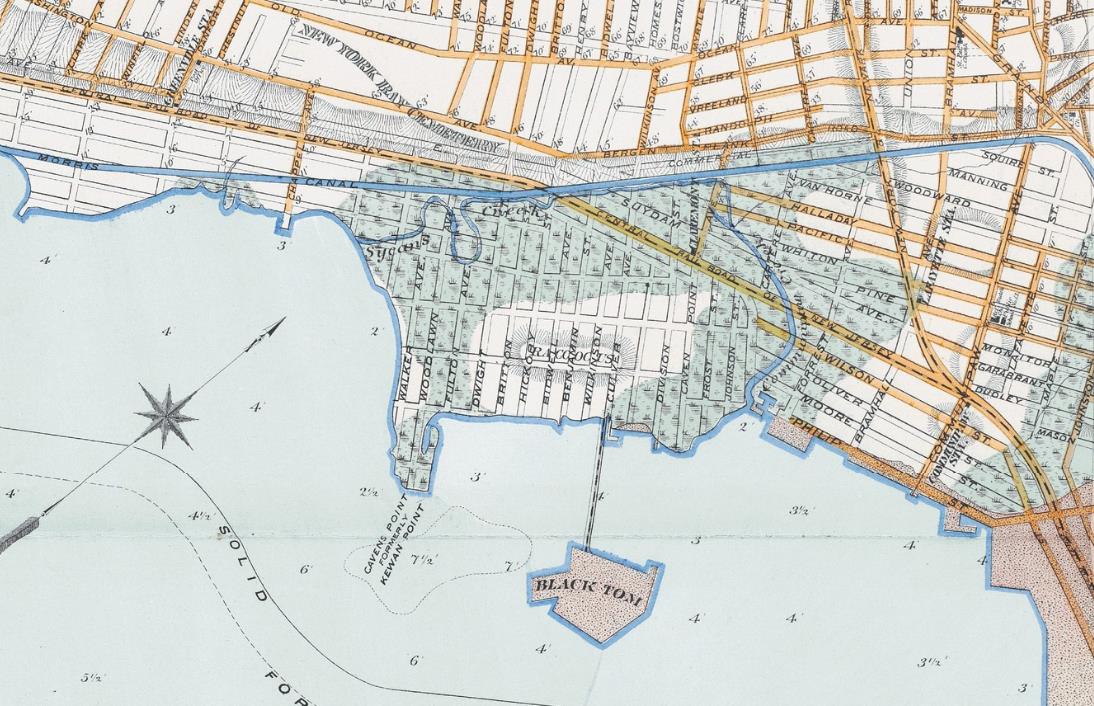

“Black Tom” originally referred to an island in New York Harbour next to Liberty Island. The island was artificial, created by land fill around a rock of the same name, which had been a local hazard to navigation. By 1880, the island was transformed into a 25 acre promontory with a causeway and railroad built to connect it with the mainland and was used as a shipping depot. Between 1905 and 1916, the Lehigh Valley Railroad, which owned the island and causeway, expanded the island with land fill and the entire area was annexed by Jersey City. A mile-long pier on the island housed a depot and warehouses for the National Dock and Storage Company.

Black Tom was a major munitions depot for the North Eastern United States. Until early 1915, US munitions companies could sell to any buyer. After the blockade of Germany by the Royal Navy, however, only the Allied powers could purchase from them. As a result, Imperial Germany sent secret agents to the United States to obstruct the production and delivery of war munitions that were intended to be used by its enemies.

On the night of the attack, about 2,000,000 lbs of small arms and artillery ammunition were stored at the depot in freight cars and on barges, including 100,000 lbs of TNT on Johnson Barge No. 17. All were waiting to be shipped to Russia. Jersey City's Commissioner of Public Safety, Frank Hague, (photo below) later said he had been told the barge was "tied up at Black Tom to avoid a twenty-five dollar charge”.

Just after midnight on 30th July 1916, a series of small fires were discovered on the pier. Some guards fled, fearing an explosion. Others attempted to fight the fires and eventually called the Jersey City Fire Department. At 2:08 am, the first and larger of the explosions took place, the second and smaller explosion occurring around 2:40 am. A notable location for the first major explosion was around the Johnson Barge No. 17. The explosion created a detonation wave that travelled at 24,000 feet per second with enough force to lift firefighters out of their boots and into the air. Fragments from the explosion spread out over long distances. Some lodged in the Statue of Liberty and some in the clock tower of the Jersey Journal building in Journal Square, over a mile away, stopping the clock at 2:12 am.

The explosion was the equivalent of an earthquake measuring between 5.0 and 5.5 on the Richter scale and was felt as far as Philadelphia (100 miles). Windows were broken as far as 25 miles away, including thousands in Lower Manhattan. Some window panes in Times Square were shattered. The stained glass windows in St. Patrick's Church were destroyed. The outer wall of Jersey City's City Hall was cracked and the Brooklyn Bridge was shaken. People as far away as Maryland (280 miles) were awakened by what they thought was an earthquake.

Property damage from the attack was estimated at $20,000,000 (equivalent to $470,000,000 now). On the island, the explosion destroyed more than one hundred railroad cars, thirteen warehouses, and left a 375 feet-by-175 feet crater at the source of the explosion. The damage to the Statue of Liberty was estimated to be $100,000 ($2,350,000 now) and included damage to the skirt and torch.

Immigrants being processed at Ellis Island had to be evacuated to Lower Manhattan. Although one contemporary newspaper report estimated that up to seven people died in the attack, four did definitely die- a Jersey City policeman, a Lehigh Valley Railroad chief of police, a ten-week-old infant, and the barge captain.

In the immediate aftermath of the explosion, two watchmen who had lit smudge pots to keep away mosquitoes were questioned by police but the police soon determined that the smudge pots had not caused the fire and that the blast had likely been an accident.

Soon after the explosion, suspicion fell upon Michael Kristoff, a Slovak immigrant. Kristoff who would later serve in the United States Army in World War 2, admitted to working for German agents transporting suitcases in 1915 and 1916 while the US was still neutral. According to Kristoff, two of the guards at Black Tom were German agents. It is likely that the bombing involved some of the techniques developed by German agents working for German Ambassador Count Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff and German Naval Intelligence Officer Franz von Rintelen, using the cigar bombs developed by Dr. Walter Scheele.

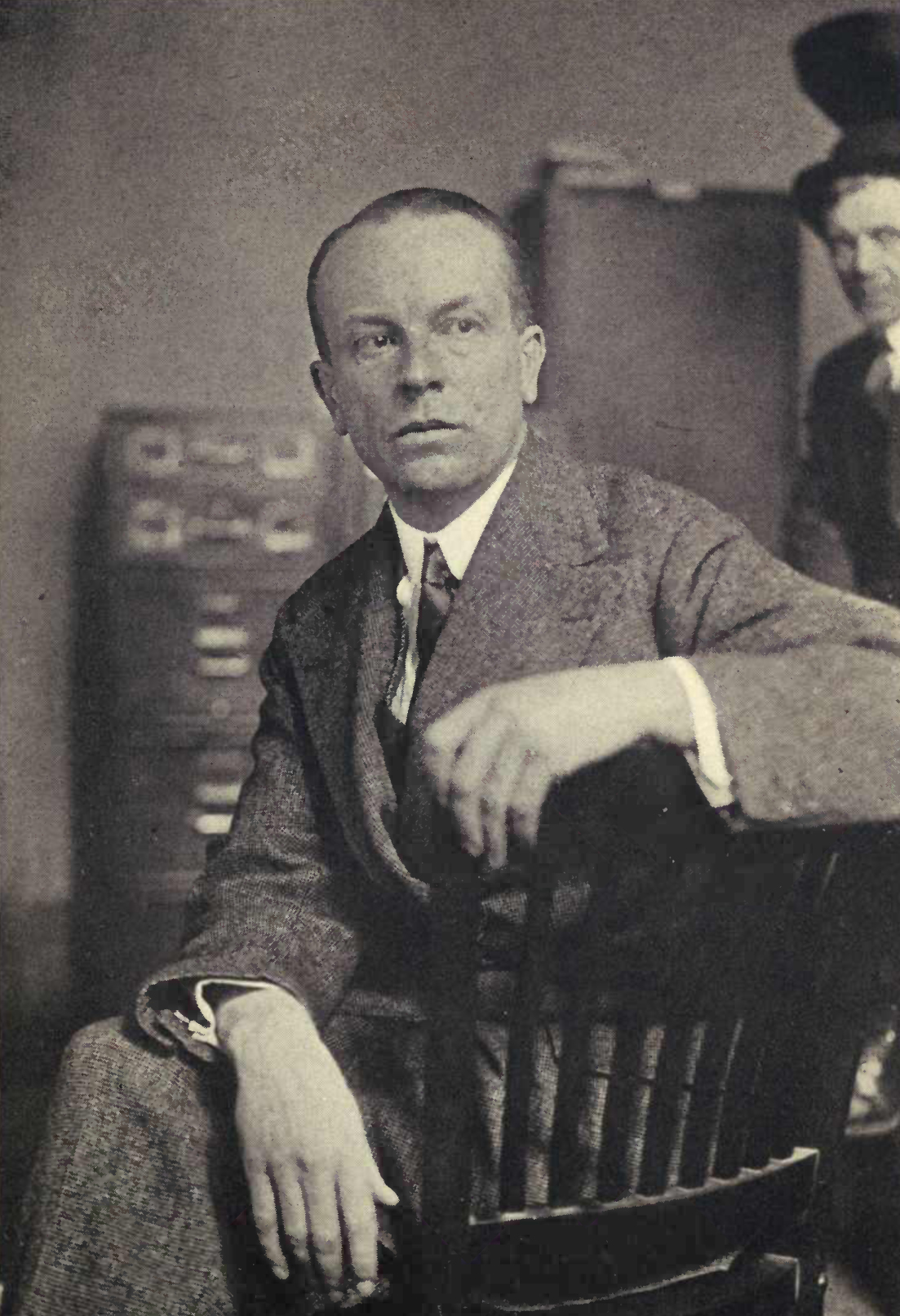

Von Rintelen (photo below) used many resources at his disposal, including a large amount of money. Von Rintelen used this money to make generous cash bribes, one of which was notably given to Kristoff in exchange for access to the pier. Suspicion at the time fell solely on German saboteurs such as Kurt Jahnke and his assistant Lothar Witzke, who are still judged as legally responsible. It is also believed that Kristoff was responsible for planting and initiating the incendiary devices that led to the explosions. Later investigations in the aftermath of the Annie Larsen affair in 1915 (a gun running ship) unearthed links between the Ghadar Indians conspiracy, who were expatriates, and the Black Tom explosion.

Additional investigations by the Directorate of Naval Intelligence also found links to some members of the Irish Clan na Gael group and Communist elements. The Irish-Liverpudlian socialist James Larkin asserted that he had not participated in active sabotage, but had encouraged work slowdowns and strikes for higher wages and better conditions in an affidavit to the lawyer John J McCloy in 1934, when McCloy was a legal advisor to the US government. There was not an established national intelligence service at the time of the explosion, other than diplomats and few military and naval attaches, making the investigation difficult. Without a formal intelligence service at the national level, the United States only had rudimentary communications security and no federal statute forbidding peacetime espionage or sabotage. This made the connections to the saboteurs and accomplices almost impossible to track.

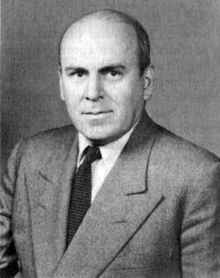

John J McCloy

This attack was one of many during the German sabotage campaign against the United States. It was notable for its contribution to the shift of public opinion against Germany, which eventually resulted in American support to enter World War One.

The Russian government sued the Lehigh Valley Railroad Company operating the Black Tom Terminal on grounds that due to lax security there was no entrance gate and the territory was unlit which permitted the loss of their ammunition. They argued that due to the failure to deliver them the manufacturer was obliged by the contract to replace them.

The Lehigh Valley Railroad, advised by their then lawyer McCloy sought damages against Germany under the Treaty of Berlin from the German-American Mixed Claims Commission. The Mixed Claims Commission declared in 1939 that Imperial Germany had been responsible and awarded $50 million (the largest claim among others) in damages which Nazi Germany refused to pay. The issue was finally settled in 1953 at $95 million (interest included) with the Federal Republic of Germany. The final payment was made in 1979.

The Black Tom explosion resulted in the establishment of domestic intelligence agencies for the United States. The Police Commissioner of New York, Arthur Woods, argued,

"The lessons to America are clear as day. We must not again be caught napping with no adequate national intelligence organization. The several federal bureaus should be welded into one and that one should be eternally and comprehensively vigilant."

The explosion also played a role in how future presidents responded to military conflict. President Franklin D. Roosevelt used the Black Tom explosion as part of his rationale for the internment of Japanese-Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

The incident also influenced public safety legislation. As a result of the sabotage techniques used by Germany and the United States' declaration of war on Germany, it led to the creation of the Espionage Act passed by Congress in late 1917. Landfill projects later made Black Tom Island part of the mainland, and it was incorporated into Liberty State Park.

Life as a Civilian Internee in Baghdad

Caroline Adams

In December 1913, Gladys Levack arrived in Baghdad along with her brother James and his wife Nora. Aged 32 and unmarried, she may have hoped to find a husband among the predominantly male European community in Baghdad or she may have come as family support to her newly married sister in law. Either way, it looked a better bet than being immured in a Yorkshire village with her mother! Nora’s father, Fredrick Parry, had worked in Baghdad for many years for Lynch Brothers, Merchants and had recently returned to England as managing director of their London head office. James Levack was a prominent member of the European/American community in the city. His “day job” was manager of the Baghdad branch of David Sassoon’s extensive trading empire, but he was also a Director at Large for the American Chamber of Commerce for the Levant and Honorary American Vice Consul for Baghdad.

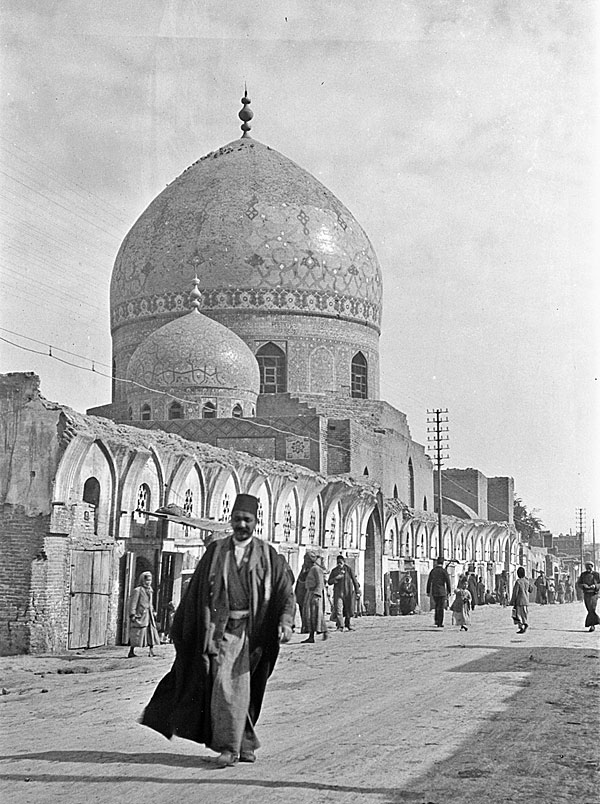

Baghdad street scene with a mosque

The European/ American community had a protected position in the Ottoman Empire, thanks to the Capitulations. These international agreements had been devised in the 16th century when the Ottomans were militarily and financially strong and needed international trade. They granted:

- Freedom of travel within the Ottoman Empire

- Freedom of religion

- Freedom to trade with no tax except a bilaterally agreed customs duty

- Freedom from the Ottoman judicial system. Subject to the laws of their own country, with courts set up by their own consuls.

For the Ottomans, the main problem by the 20th century was the bilaterally-agreed customs duties. As the empire became weaker, these became unilaterally imposed, to the detriment of the already poor Ottoman economy.

For Gladys, life in Baghdad was good in early 1914. The city was fascinating and beautiful and, with James and Nora, she would have been quickly accepted into a vibrant social life. But it was 1914. (Photo below – the British residency).

During the July crisis, many of the Gladys’s community probably felt quite secure. It was all so far away and, protected by the capitulations, even the Balkan wars had had little effect on their everyday lives. As the Ottomans declared full military mobilisation in August, though, some would have started to worry. But on 9th September, 1914, the crisis hit them in earnest. The Ottomans unilaterally abolished the Capitulations. Suddenly, they were cut adrift, unprotected in a foreign country. At first it was the taxation which hit them. Taxes went up on all non-essentials, including tea, coffee, and tobacco. Goods were requisitioned from businesses and “voluntary” contributions demanded from businesses and individuals. Refusal to pay would leave them subject to the Ottoman judicial system.

On 29th October, 1914, the Ottoman ships, the Goeben and the Breslau, opened fire on the Crimean Black Sea Fleet and shelled the Russian coast. On 2nd November, 1914, first Russia and the Britain and France declared war on the Ottoman Empire and that afternoon, Ottoman troops surrounded the British Residency in Baghdad. Over the next few weeks, British and French business men in the city were rounded up and interned in the British Residency and on 13th December, 1914, 41 people were deported from the city on a two month journey to the port of Mersin from where they sailed to Port Said and on to Bombay.

Transport of the era – Gertrude Bell’s caravan near Baghdad, 1909

Left in Baghdad were about 2,500 Indians (citizens of the British Empire), the Sepoy Guard from the Residency who were taken to the Ottoman barracks, about 10 British women and 10 children and several British business men. At least two of the latter were too ill to travel but Mr Walker of Lynch Brothers and James Levack of Sassoon’s seem to have been kept to assist the authorities in their requisitioning of the stores from their respective employers. It may also be that James’ position as Honorary American Vice Consul made his nationality unclear. America was not in the war at that time and in fact never declared war on the Ottomans.

Even without the war, Baghdad would have been difficult that winter. In December, the Tigris rose unusually high. Houses were flooded and many thousands of people were left homeless. In January and February, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague. At its worst, 40-50 people were dying each week. There were occasional outbreaks of cholera. And on top of all that, there was the war causing high taxes, food shortages and harassment from the authorities.

Harassment was probably worst for the British Indians. Most were Moslem and therefore, especially after the announcement of jihad, the Ottomans expected them to join their army. Most did not want to. Some were deported to India, but few had friends or family there. Those who stayed were further taxed and harassed. The British Government sent money to support them via the American consular system. Baghdad was fortunate in having Charles Brissel as American consul. He worked tirelessly to support civilian internees and prisoners of war, diplomatically, financially and logistically. James may have been able to assist him at first but it soon became clear that the safest thing for the remaining British to do was to stay at home unless their presence was requested by the Ottoman authorities. They were highly suspicious of the enemy aliens in their city and unpredictable in their dealings with them. Brissel wrote twice to the British authorities asking them to stop British in Basra trying to contact friends and family in Baghdad as this was leading to accusations of spying.

There is further detail in a letter from Brissel to Henry Morgenthau, the American Ambassador in Constantinople, dated 26th July, 1915. At least two British men had been deported from Baghdad to Deir el Zor, Mr Johnson and Mr Barter. Brissel details that Barter was told by the police that he was not a prisoner and could go to and from his business as he liked. Despite this, he was suddenly taken to the police headquarters and kept there till deported, despite being assured he was not guilty of any misconduct. He had to travel in the summer heat despite being unwell. Consequently, Brissel said, Mr Walker kept to his house except when required by the authorities to attend Lynch’s offices to assist with the liquidation of the business. There, he was forced to make up the accounts as instructed. No payment was being made to Lynch’s for the goods and none to Walker for his work. As with all the remaining British citizens, the American Consulate was supporting them financially and requesting reimbursement from the British Government.

James Levack is specifically mentioned as well. Like Walker, he was also keeping to his house unless his presence was requested, “with the exception of the day he went to bury his son”, two weeks before. This child could not have been more than 18 months old. Shortly after this, the police arrived at the Levacks’ home to take James to police headquarters. They could give him no information as to why he was wanted. As Barter had been deported a short time before, he feared the worst and believed he was making his final goodbyes to his wife and sister. In the event he was simply required to adjudicate between a merchant and a government agent on the correct price of sugar! He returned home the same day, none the worse, and returned to the task of selling the remaining stock from Sassoon’s. This had been returned to him a few months previously, presumably after the government had taken anything it considered useful to the war effort.

All this time, the Indian Expeditionary Force (IEF) had been making its way up the Tigris. By the time they arrived at Amara, they had captured about 50 Ottoman civilian officials. A plan was proposed to swap these gentlemen for the British women and children and the Residency Sepoy Guard, still in Baghdad. But the proposal was finally rejected by the Ottomans. Although it was revived in different forms over the next two years, no swap appears to have taken place.

With that hope dashed, the internees in Baghdad continued to survive as best they could, but by November, the IEF was approaching the city and Baghdad was filling up with Ottoman troops. It was time for the authorities to get rid of any British who might try to get information through to the IEF. Two people had managed that in February, and they would not take the risk of it happening again. Early in November, 1915, the Walkers and the Levacks left Baghdad in the direction of Mosul. The Walkers had a small child and Nora Levack was five months pregnant. This was the start of a year long journey that would finally take them to Constantinople, about 1,500 miles away. They would all arrive there, complete with baby Betty Levack, born in Mosul, but Mrs Walker died in Constantinople. Nora and James returned to England after the war, by that time with two children. James came back to Baghdad to manage Sassoon’s in 1919. Gladys survived the war but died in a military hospital in Thessaloniki on 16th December, 1918, just another fragment of the collateral damage of the Great War and a sad end to her escape from a Yorkshire village.

References

A Lady in a Salonica CWGC Cemetery. Caroline Adams.

https://www.nwwfa.org.uk/index.php/articles/a-lady-in-salonika

Record Group 84. Volume 19 (1915) American Archives

Photographs by courtesy of Newcastle University online archive of the letters, diaries and photographs of Gertrude Bell

Book Review

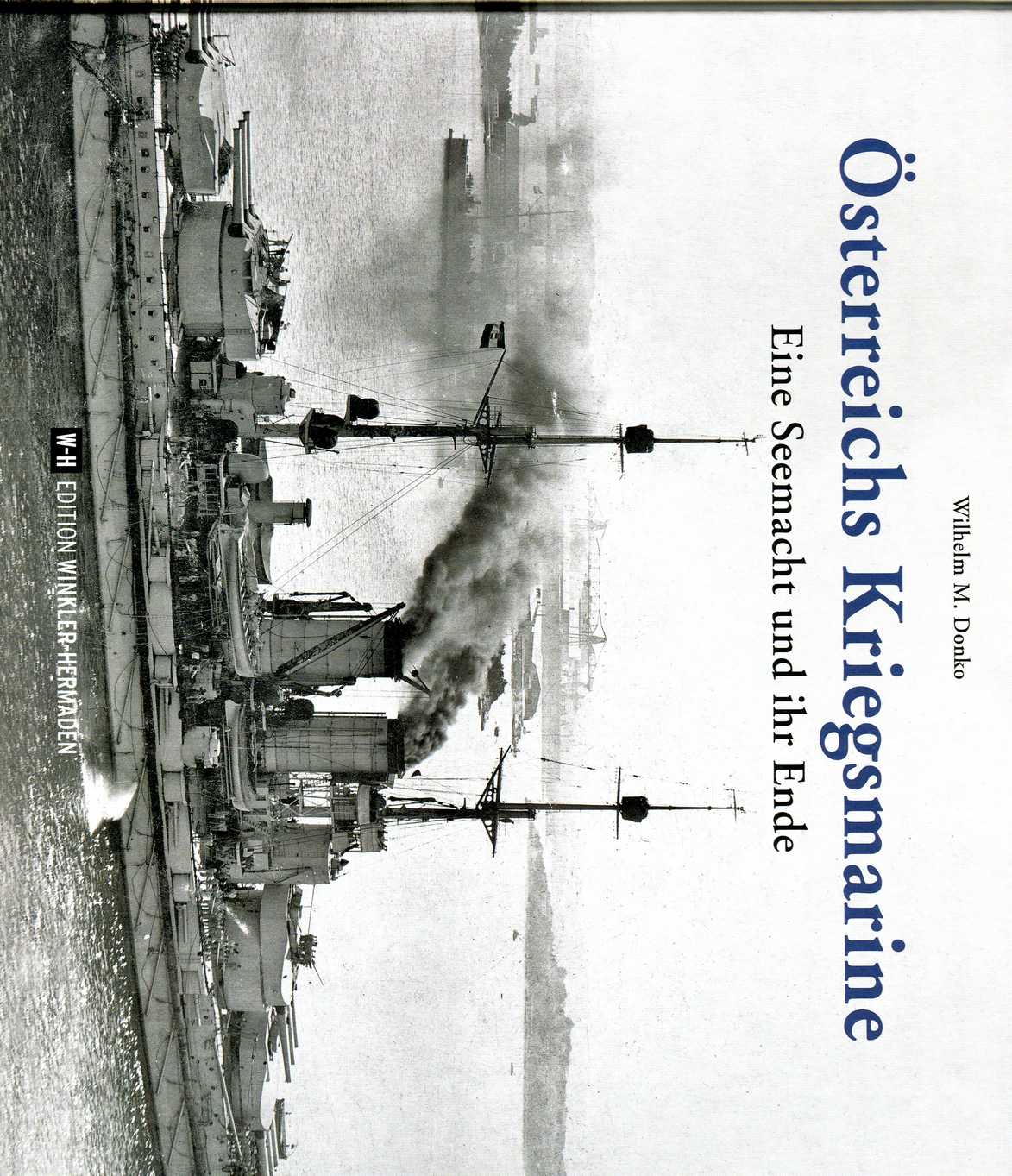

Austrian Navy

A sea power and its end

Wilhelm M Donko

Edition Winkler-Hermaden, Schleinbach, 2018

Well, did you even know that there was an Austrian navy? My first inkling of this aspect of WWI was when I visited the army museum in Vienna, a few years ago, and found a room of models and old photos of the navy. This book is a tribute to a navy that is forgotten in its own country, yet was a middle-ranking sea power in its day.

The author is in fact the Austrian ambassador to Norway. He has, however, a fascination with marine history and has written extensively on the topic.

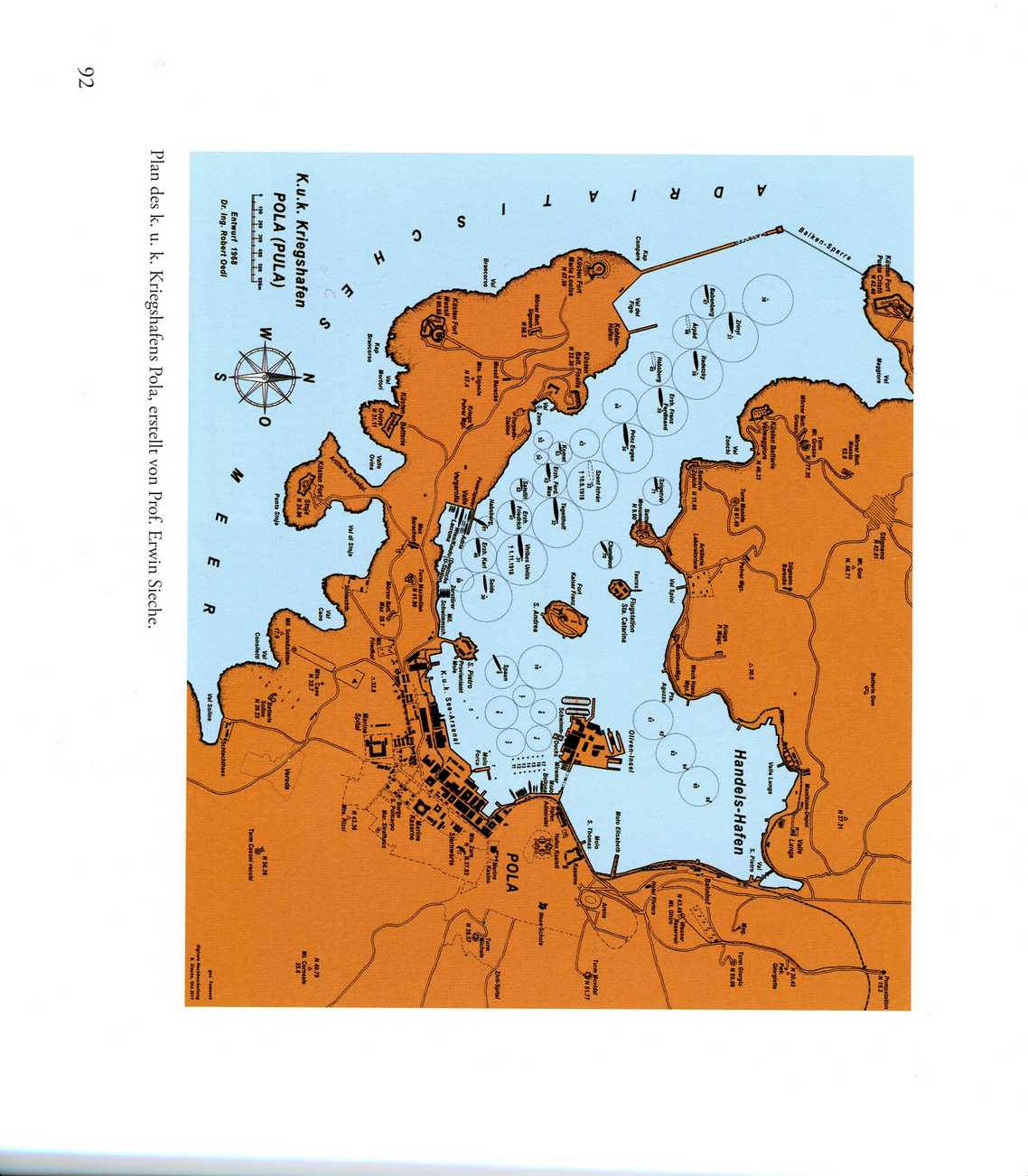

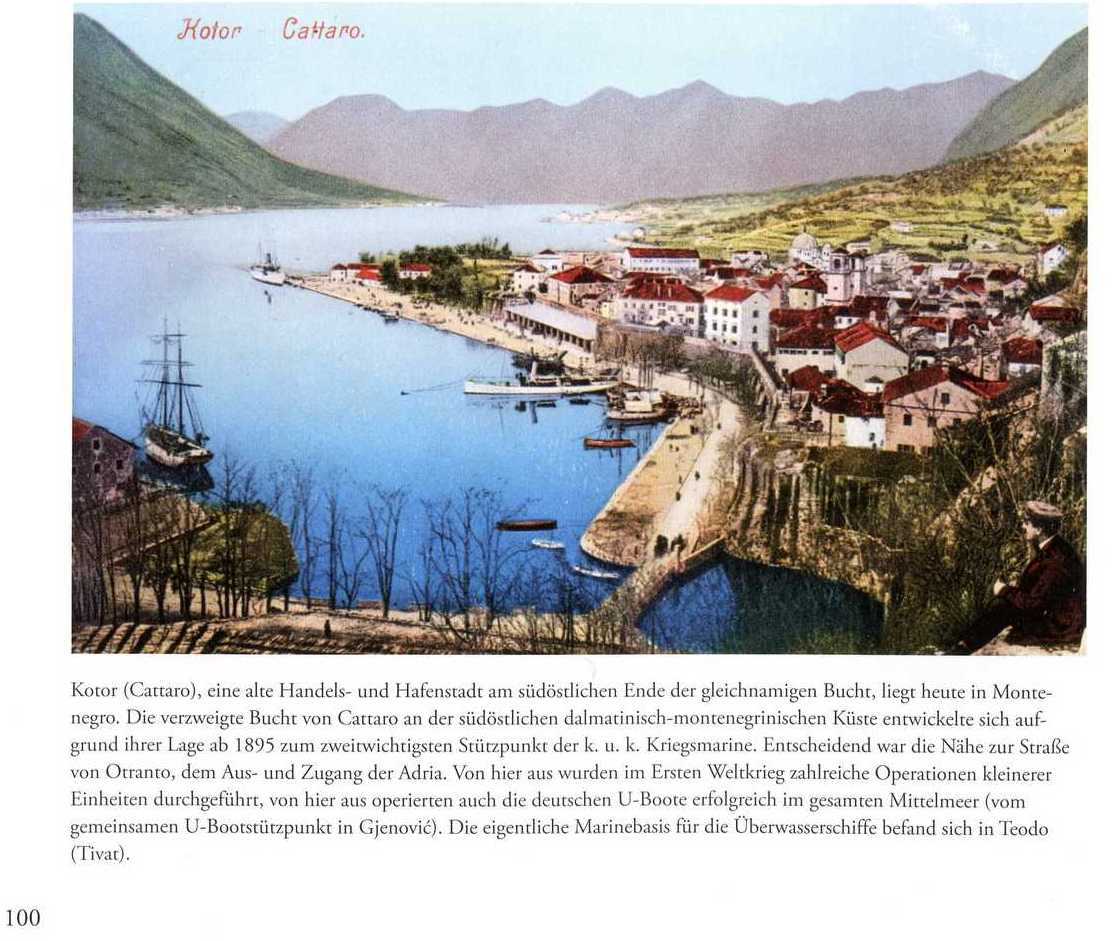

The book starts in modern Pula in Croatia, on the shores of the Adriatic. The author describes the modern scene and explains the naval origins of buildings and features of the town, for this was the principal port for the Hapsburg navy. Pula (Pola) is a wonderful natural harbour and was the obvious choice for a naval base. Trieste, now in Italy, was a major port for the Hapsburg regime but was a commercial centre rather than a military one. Fiume had a role as well, as it was the location of the officer training school and a shipyard. Today, Fiume is Rijeka in Croatia. Kotor (Cattaro) at the south eastern end of the Adriatic coast was another base which was used as a base for German U-boots in WWI. Today it is in Montenegro. Nearby Gjenovic was also used as a U-boat base. Surface ships were based in Teodo (Tivat on the bay of Kotor in Montenegro).

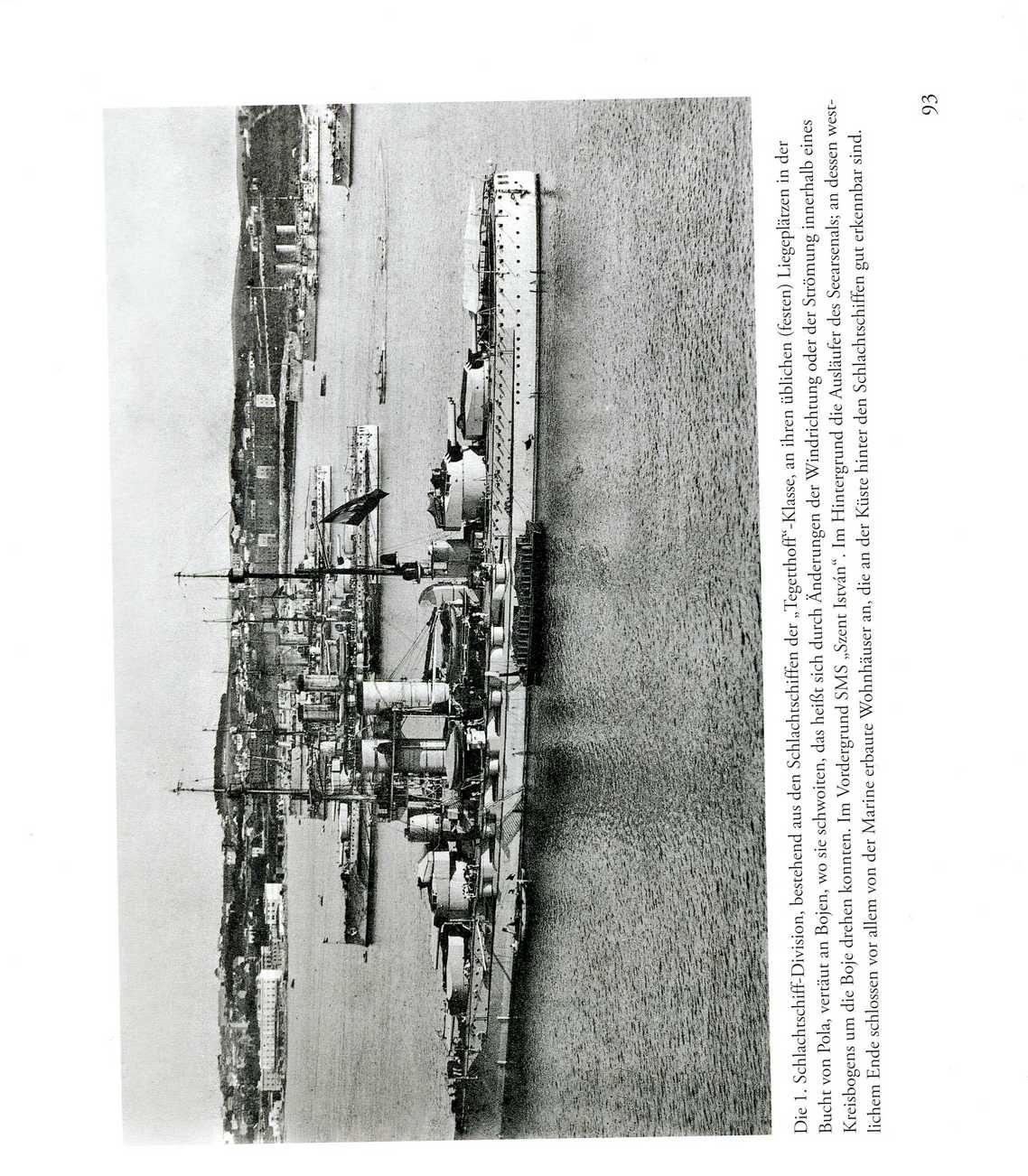

The battleships – Tegetthoff class “dreadnoughts”

The 18th and 19th century origins of the navy are discussed. One issue, always, with any Hapsburg entity is the nationalities involved. So, in the beginning Italians were very much involved. Given the seafaring traditions of, for example, the Venetians this is hardly surprising. With Italy becoming an independent country in the mid 19th century and struggling against Austrian control, there was a move afoot in the Austrian navy to remove Italian influence. Italy, in effect, became a rival across the Adriatic from Austro-Hungary. So, the navy cadre became much less Italian and much more like the Austro-Hungarian army, ie with the German-speakers as the biggest nationality but with a considerable contribution from other nationalities, notably the Croatians.

In the period leading up to WWI, the Austrian navy was modernised and expanded. There were shipyards in Pula and Trieste, so they could build their own ships. The Hungarians insisted that one of the four new dreadnought class battleships had to be built by them, which indeed one was, in Fiume. So, at the outbreak of WWI the Austrian navy had four of the cutting-edge dreadnought class battleships. In the navy nomenclature, they were Tegetthoff class, named after a visionary head of the navy who died in 1884 at the age of 43 of pneumonia, in Vienna not on his ship. There were also non-dreadnought battleships, heavy and light cruisers, destroyers and torpedo boats. One of the ship designers was British. His niece, in 1912, married a naval captain called von Trapp, whose offspring were later the subject of the Sound of Music.

The great natural harbour at Pula (today Pola in Croatia)

The sphere of influence for the Austrian navy was the Mediterranean and the Adriatic, although the ships did go further afield. The cruiser Kaiserin Elisabeth was caught in TsingTao, a German colony, when Japan attacked on 27th August 1914. She fought on for some weeks, until her ammunition ran out, and she was scuttled by her crew. The Mediterranean was an important route for shipping going to and from the Middle and Far East, notably India. In WWI, Australian and Indian troops were brought into France through the Mediterranean, and the British went east to Mesopotamia, Palestine, Gallipoli and Salonika. A hostile navy running rampant could have caused a lot of damage.

During WWI, however, the Austrian navy remained bottle up in the Adriatic by a French blockade. It was too dangerous for the French, or indeed the British, to enter the Adriatic because of the Austrian submarines. Germany supported Austro-Hungary by sending disassembled submarines over land to Pola where they were re-assembled. The Germans soon discovered that larger and better submarines could be sent by sea through the Gibraltar straights. They were stationed in the Austrian navy bases in the Adriatic. By 1918, there were two flotillas of German submarines operating from Austrian bases.

By October 1918, it was really all over for the Austrian navy. The big ships were divided up between Italy, France and Britain. The USA, Romania, Portugal and Greece were allocated the lesser ships. The country which we would know as Yugoslavia did not inherit the Austrian navy, not least as the Italians did not want another naval power in the Adriatic. Indeed, Italian navy divers sank the flag ship Viribus Unitis on 1st November 1918 in Pola harbour to prevent it falling into the hands of Yugoslavia. Four hundred sailors died.

So disappeared from history the Austrian navy. As the author points out, there was a key factor which the Austro-Hungarian and German governments failed to understand in following the doctrine of the American Alfred Thayer Mahan in his book The Influence of Sea Power upon History. That was, the importance of having strategic overseas naval bases, as well as powerful ships. If the Austrian or German navies had broken out through the Entente blockades, where could they have gone? This was the Achilles heel of both navies.

The book has some wonderful photographs. Indeed, the picture postcard was apparently an Austrian invention, so there are a selection of picture postcards illustrating the ships and bases of the Austrian navy. It is an interesting book with lots of photos on a neglected aspect of WWI. The book is in German.

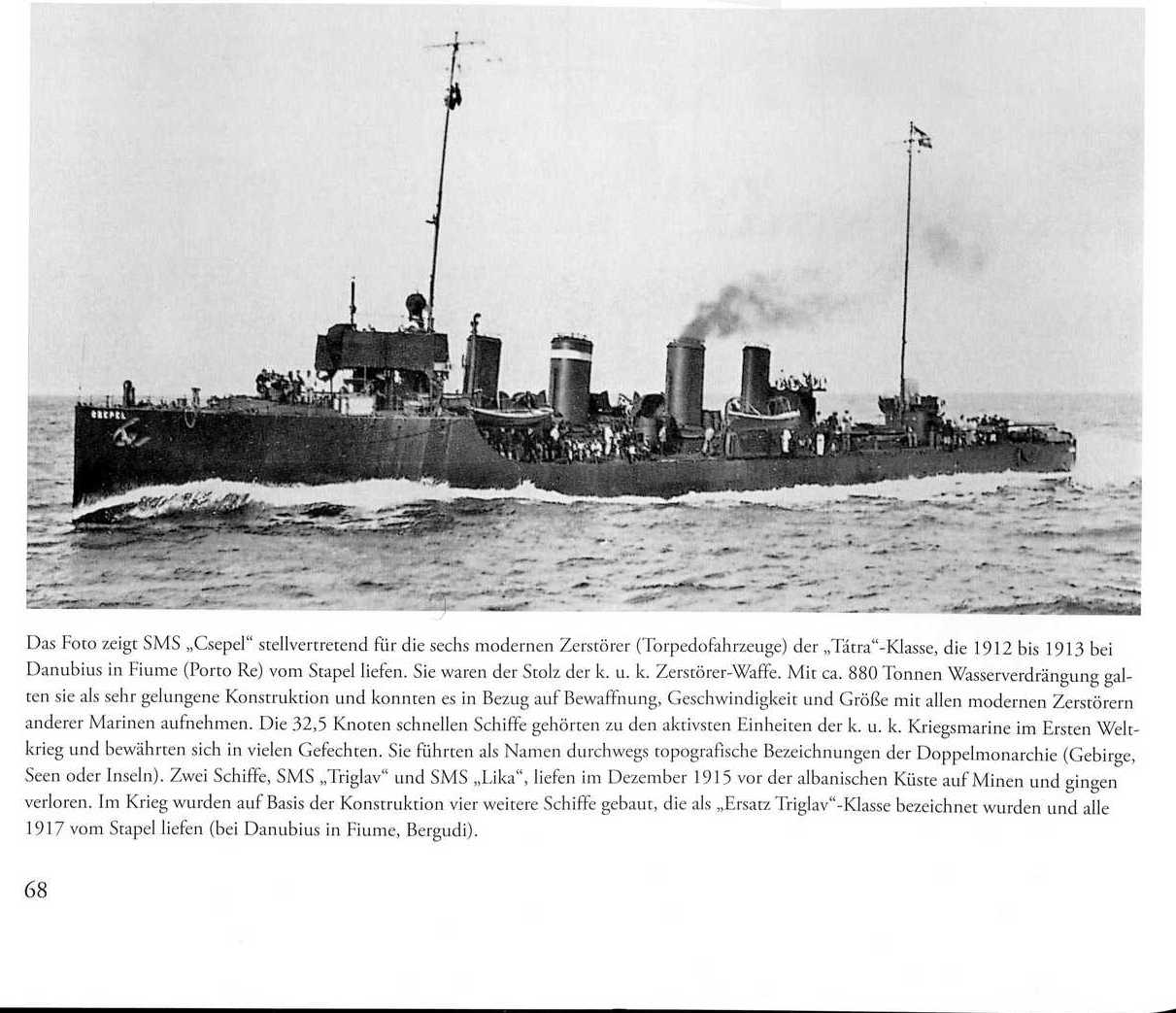

Destroyer “Csepel” (which is the name of an island in the Danube, today in Hungary), a new class built in 1912-1913 which could do 32.5 knots, and took part in various WWI actions

The harbour at Kotor (today Cattaro in Montenegro) which was the base for German U boats for the whole Mediterranean in WWI

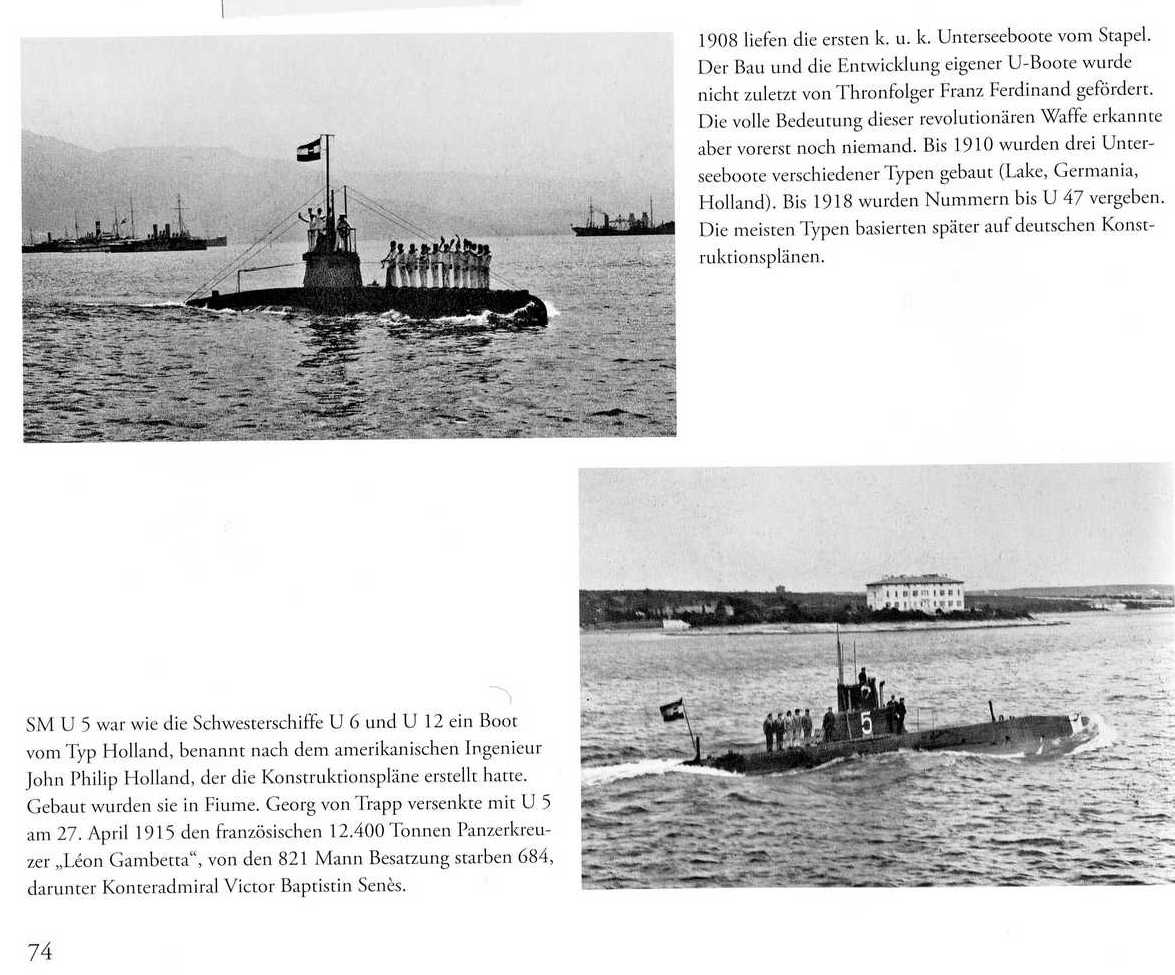

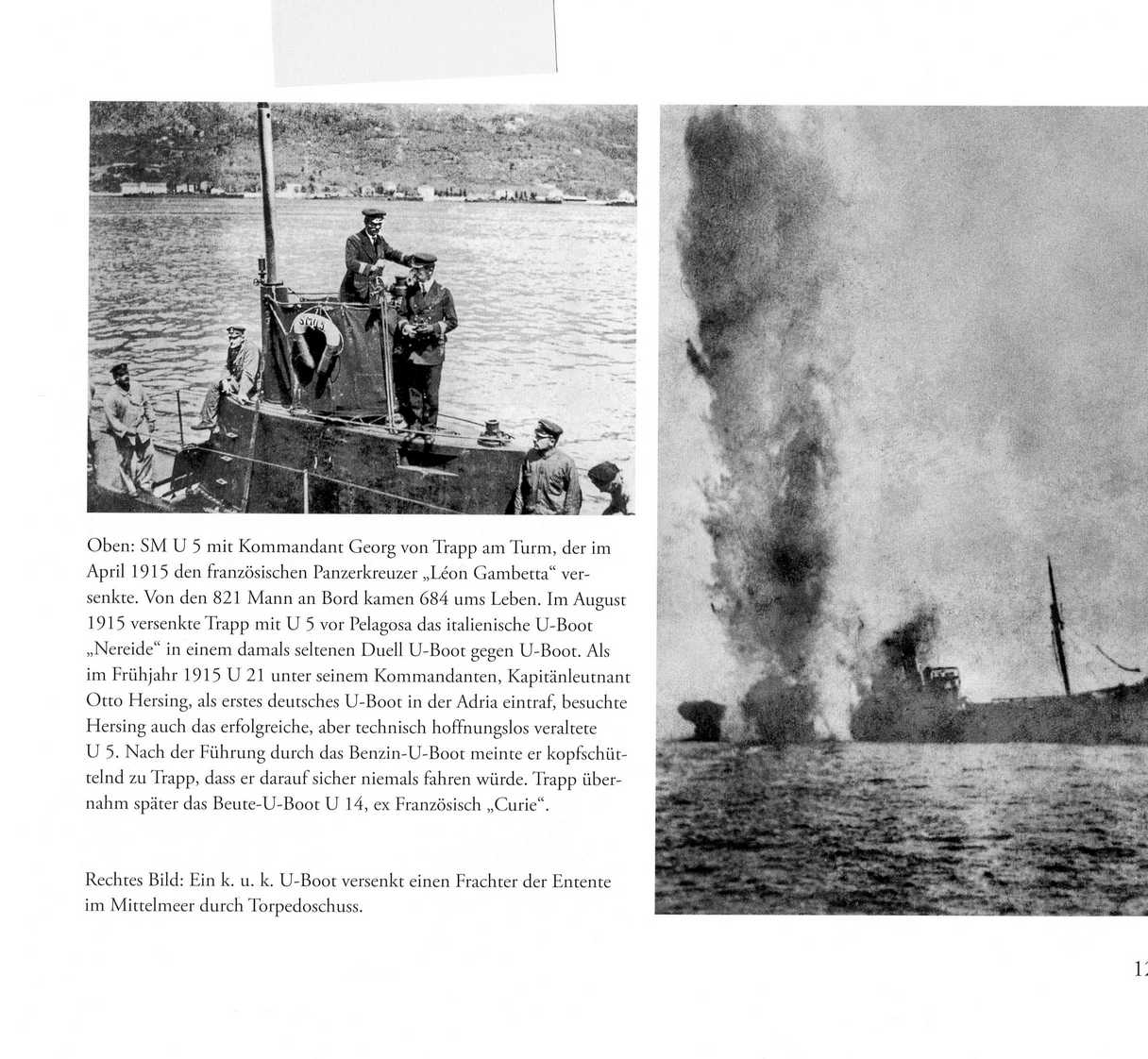

The Austrian navy had U boats from 1908. The captain at the start of WWI of U5 was Georg von Trapp, father of the “Sound of Music” children. He is in the left hand photo below.

U5 was petrol-powered, and was decommissioned early on in WWI, but not before it had sunk the French heavy cruiser Leon Gambetta, with the loss of 684 lives.