The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have articles by Terry Jackson on PoWs, in particular the work of the curiously named Queen Victoria’s Fund Jubilee Association, two articles by Keith Walker on a forgotten nurse casualty, and tracking a Military Medal recipient. Finally, we have a review of a book by the dynamic Professor Alexander Watson on the siege of the Fortress of Przemsyl, which arguably stopped the Russians from invading Austria and southern Germany. The book also describes the considerable internal problems of the Austro-Hungarian army (with eleven languages in use).

For obvious reasons, we have no face to face branch meetings for the foreseeable future, but there is a Zoom meeting (of the Stockport branch) coming up, which anyone can join in.

Zoom Meeting: Bill Mitchinson on the Italian Army and the Eleven Battles of the Isonzo

Time: Feb 12, 2021 07:45 PM London

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/83413647642?pwd=V1FObElRcEhEVEV5T1cvamRtRTVDUT09

Meeting ID: 834 1364 7642

Passcode: 324521

The Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Fund Association

Terry Jackson

As well as the Red Cross, The Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Fund Association, Rue Muzy No. 15, Geneva, had special permission from the German Authorities to enquire about missing soldiers in the camps and hospitals in the war zone in Germany and Belgium. It circulated illustrated sheets with pictures of the missing.

The Enquiry Branch of the Association was created by Mr. S. Goodman, also known as Mr Guttmann (the Germanised version of his surname). He was a retired British officer of the Indian Postal Department and was living in Geneva. Some documents have suggested that he was a representative of the British Council in Geneva.

The work began in November 1914, when Lady Bullough asked Goodman to help find her brother, Captain Charles de la Pasture of the Scots Guards, since the Red Cross International Committee could not help. Goodman decided to send handwritten circulars to a number of PoW camps in Germany. When this proved successful (de la Pasture was killed 29 October 1914 aged 35), he received enquiries about other British officers who were missing in action. He then asked for photos which were attached to the circulars. As the project continued, Goodman combined the photos into a 'tableaux' (about 28 photos of individual officers, displayed on a sheet). (Photo above is of a painting of Captain de la Pasture.)

Then, in February 1915, the Germans forbade information on PoWs being passed on to private agencies. Consequently, Goodman applied to the QVJFA for permission to use their name. This organisation provided assistance to needy British subjects in Geneva. The QVJFA agreed and Goodman was appointed Honorary Manager of the Association’s Enquiry Branch. Despite this, for most, if not all of the war, the whole effort seems to have been run by Mr Goodman alone.

Examples of the QVJFA’s work included: Capt. Noel William Ward Webb MC, a Flight Commander in the Royal Flying Corps was posted as missing in action on 16 August 1917. He had subsequently been reported by the QVJFA as being killed on that date (photo below).

Second Lt. Thomas Wright Carson served in 6th West Riding (Duke of Wellington’s) Regiment. On 7 January 1917, his family was told he was missing in action by his unit, but they said it did not necessarily mean he was dead. He had been in France less than eight weeks. His brother was in the same regiment but could not say whether he was dead or captured.

While Thomas was out in No Mans’ Land with a couple of men on a raiding party, a flare went up and they took cover. When the flare died out, the other men looked for Thomas but there was no sign of him, nor could later patrols find him. It was assumed he had been captured as no shots had been fired. However four months later his brother was informed by the QVJFA that Thomas Wright had died on 27 December 1917.

The letter from the QVJFA to Thomas Wright Carson’s family read: “Dear Sir, We are grieved to be the bearers of sad news about your brother Thomas. We have received the following information from Countess E. Blucher von Wahlstatt in Berlin. She saw in our last list of missing officers the name of 2nd Lt. Carson, missing near Ypres, and wrote to tell us that a German officer on leave had told her that they came upon his body and later buried him with full military honours”.

By the end of the war the organisation had been operating for four years. Its lists had been sent to PoW camps in Germany, Belgium and occupied France, featuring around 400 names, including some French troops with details on a French corporal and a private, but only officers seem to have been featured in the British lists.

In total, 92 lists were circulated. Those enquiring about missing soldiers also received a copy of the list that included their relative, which was perhaps a small comfort to them. Enquiries were made amongst prisoners of war interned in Switzerland, although little information was obtained this way. Attempts to extend the branch’s enquiries to PoWs held in Turkey and Egypt were not successful.

Initially the whole project was funded by Mr Goodman and donations from some enquirers. After these funds ran out in May 1918, photographs were only included in lists if the enquirer contributed the cost of reproduction (8/-). As funds improved, smaller donations could be accepted. The branch’s success meant that people enquiring to the British Central Prisoner of War Committee about relatives who they thought might be PoWs were sometimes directed to it.

Some of the reasons for the branch’s success were judged to be co-operation with various German aid societies, and the goodwill created in Germany due to the branch circulating some lists of German PoWs around British PoW camps. After a while, Mr Goodman began to liaise with the German Red Cross Association. He responded to an enquiry from Princess Blucher of Wahlstatt in Berlin (referred to above) about her brother who was serving in the British army (Lt W. Stapleton-Bretherton, 4th Royal Fusiliers), This led to the Princess providing certain information on British PoWs in Germany.

The branch’s post-war report states that superstitious men sometimes threw their identity discs away before going into action for fear that they could bring harm to wearer! This obviously did not help identify those missing in action.

The Swiss Catholic Mission at Friburg occasionally obtained information from the Germans about British aviators, sometimes as soon as eleven days after they were killed or reported as captured which was a quick response in the circumstances.

Footnote.-The fates of the airmen are recorded, all of whom were killed in action.

Noel William Ward Webb MC & Bar, age 20 had 14 victories including the German ace Otto Brauneck on 26 July 1917.

Ward Webb was subsequently downed by Werner Voss, 3 days later near Polygon Wood.

Voss age 20 was shot down on 23 September 1917 over Poelkapelle, having just returned from leave and eventually being downed in a dog fight against superior numbers which included James McCudden VC, DSO & Bar, MC & Bar, MM.

McCudden, age 23, was killed in an accident on 9 July 1918.

A Slight Connection to Fame

Keith Walker

During the research on the Wrexham War Memorials you sometimes come across stories which have a slight connection to a more well-known character from the war. One such story involves a Wrexham nurse and Siegfried Sassoon CBE, MC (8th September 1886 to 1st September 1967), the well-known soldier, writer and war poet.

They were both at Liverpool Street train station in London when it was bombed. He was going from hospital to take over a cadet officer training unit at Cambridge, and she was going home on leave to Wrexham from a London hospital. Her name was Agnes Bertha Pugh (1895 to 30th October 1917). This is her story.

Agnes Bertha Pugh (known as Cissy to her family and friends) was born in Wrexham in 1895, and was the second daughter of William and Elizabeth Pugh of 14 Palmer St, Wrexham. Her father was a leather shaver, probably working at the Cambrian Leather Works in Salop Road. She was named after two of her father’s sisters. Her siblings (all born in Wrexham) were an older sister (no details), William Alexander (1897 to 1979), Sarah Jane (1899 to 1992), Addie Elizabeth (1901 to 1961) Harry (1902 to 1906), Alfred Edward (1903 to 1987), Ezra Campbell (1906 to 1908), Eric Leslie (1909 to 1909), and Harold Douglas (b 1911). By 1911, the family home was at 13 Bernard Road.

She was educated at the National School on Madeira Hill and followed her older sister into nursing.

By 1911, the family was living at 13 Bernard Road, and five years later at 110 Smithfield Road. During the Great War, Cissy went to work as a nurse in London.

On the morning of the 13th June 1917, twenty two Gotha “Giant “ GIV bombers took off from near Ghent in Belgium with the intention of attacking London. Sixteen of the machines reached the capital where they dropped a total of seventy two bombs over the City and East London. It would seem that Cissy was in Liverpool Street Station when the bombers appeared overhead.

Three bombs were dropped on the station at approximately 11.30, one of which hit platform nine, destroying one carriage of a train that was about to depart for Hunstanton and caused two carriages to burst into flames. A second bomb fell on another train the carriages of which were been used by military doctors to carry out medical examinations. It is believed that the bomb caused some oxygen cylinders to explode causing a further fire.

A total of sixteen people were killed and fifteen injured. One of the latter was Cissy Pugh (photo above left). According to family tradition, she was alongside a small boy who had been wounded and was covering him with her cloak when she herself was injured. She received treatment in London before been evacuated home to Wrexham where she was admitted to Croesnewydd Hospital. She died there on the 30th October 1917.

The war poet and author Siegfried Sassoon, serving in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, recorded his recollections of the raid in the book “Memoirs of an Infantry Officer”.

“In the trenches one was acclimatized to the notion of being exterminated and there was a sense of organized retaliation. But here one was helpless, an invisible enemy sent destruction spinning down from fine weather sky.”

The German air raid killed a total of one hundred and sixty two people and injured four hundred and thirty two others, including eighteen children killed when their school in Poplar received a direct hit. It was the most destructive German air raid of the war.

Cissy Pugh was buried in Wrexham Borough Cemetery on the 3rd November 1917 with, according to the newspaper, full military honours. Her obituary in the Wrexham Guardian noted:

Local Victim of German Vulture

We regret to learn that German atrocity towards the civil population has claimed a Wrexham victim in the person of Miss Cissy Pugh who died on Tuesday as a result of wounds sustained in an air raid whilst engaged as a hospital nurse.

She attended the Church of England School at Wrexham both for educational and religious purposes and her death is deeply felt by all the teachers and pupils who will always remember her as a kind loving and generous personality. Her motto ever was “Be brave and do your duty”, and to the end she always lived up to it, as rather than shirk her duty to the sick and wounded she remained in the danger zone and consequently met her death.

Cissy’s name is not recorded on any memorial in North Wales. Her grave (04164) has no headstone. Her sister nursed in Palestine during the war, and her brother William served in France with the 18th London Regiment (London Irish) and the 15th Royal Irish Rifles.

Notes

William Alexander Pugh (26th January 1897 to March 1979). Survived the war. He was married in 1921 to Gladys Pugh nee Wynn (1898 to 1974) .They had two daughters. In the 1939 register, he is living in Ormskirk and working in a butchers shop.

My copy of “Memoirs of an Infantry Officer” was published by The Folio Society, 1974. Page 217 records the bombing incident. The book was first published by Faber and Faber Ltd.

I did not find any records of Agnes Bertha Pugh serving as a Queen Alexander or a Territorial Force nurse.

References and acknowledgements

Wrexham in Memoriam, published 2020 by Friends of Wrexham Museums

Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, published 1974 by The Folio Society

Web site www.ancestry.co.uk

A Military Medal – the story so far

Keith Walker

Because of the pandemic, two of my battlefield tours in 2020 which I had booked were cancelled / postponed. So, with the money which I would otherwise have spent on the tours, I decided to purchase a Military Medal. My son Philip and I have a small collection of cap badges and medals, but we have always wanted a decoration. As a Victoria Cross was out of the question, we went for a Military Medal. We found a Military Medal complete with a World War One trio of medals awarded to a regular soldier who served in the Royal Fusiliers, at a price we could afford. This is a nice research project to keep me occupied during the time I have been shielding from this pandemic.

The information which has been found, so far:

- The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment), formed in 1686.

- In 1968, it was amalgamated with other regiments of the Fusilier Brigade to form the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers.

- The Royal Fusiliers in WWI. The 1st Battalion landed at St Nazaire in September 1914, as part of the 17th Brigade in the 6th

- The 2nd Battalion (which I believe our man was in) was part of the 86th Brigade of the 29th It sailed in March 1915 and landed in Gallipoli on 25th April 1915; then evacuated to Egypt in January 1916. From Egypt sailed to France and landed at Marseilles in March 1916.

- He is not on the CWGC site, so he survived the war.

His Military Medal was reported in the London Gazette on the 6th July 1917. From this I can only assume that the action for which the Military Medal was awarded was one of the actions which took place at the Battle of Arras, in particular the 2nd Battle of the Scarpe. The Royal Fusiliers played a part in this encounter. I have not found his citation but these are like the proverbial hen's teeth, ie hard to find.

I have deliberately not named the soldier, as I have found a couple of anomalies in his story which is not unusual in the early part of your research. So, research is ongoing. I need to find and read some war diaries, pension records etc. Watch this space for part two.

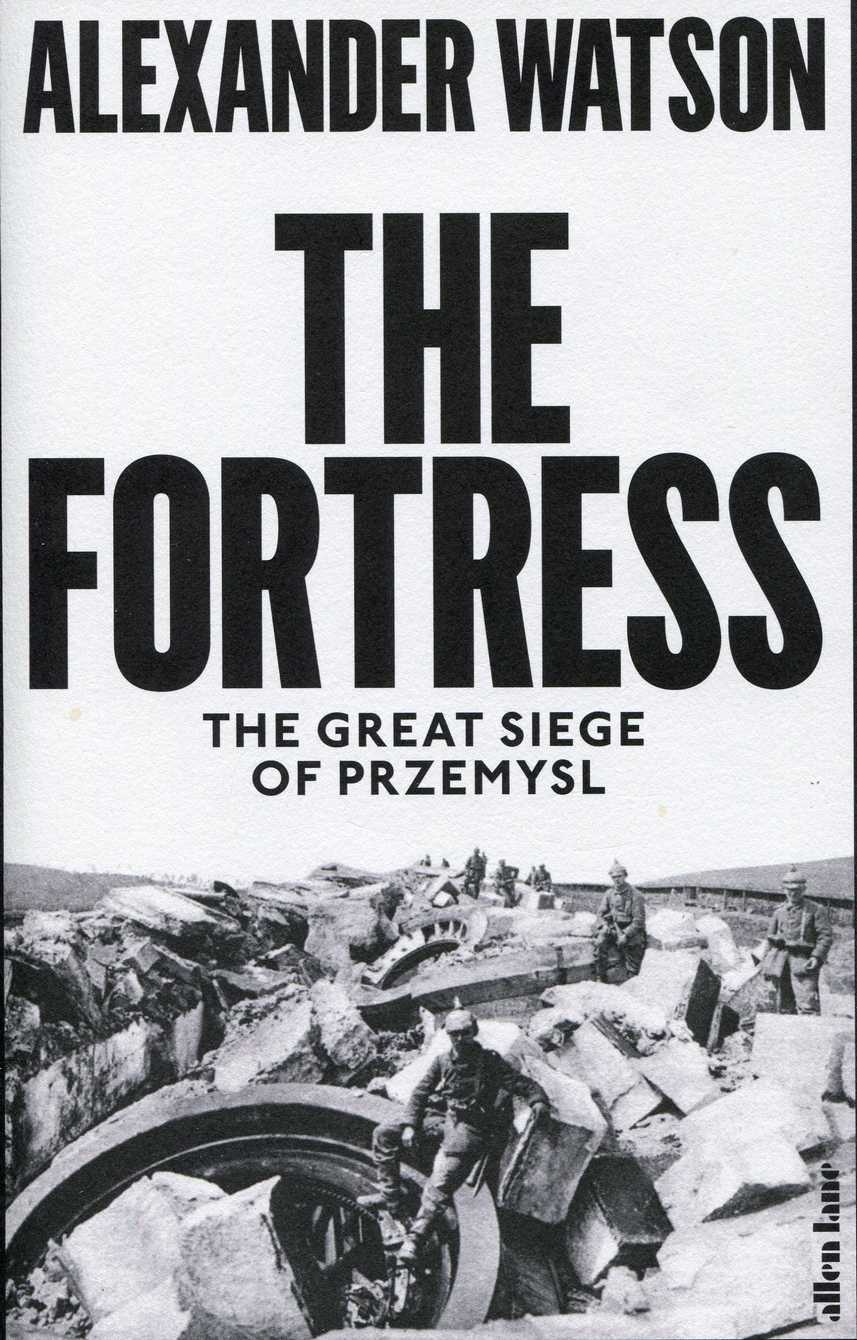

Book Review

The Fortress – the Great Siege of Przemsyl

Alexander Watson

Allen Lane 2019

Alex Watson is professor of British History at Goldsmiths College in London. He is a wonderful speaker and, if you get a chance to hear him, grab it.

Alex Watson is professor of British History at Goldsmiths College in London. He is a wonderful speaker and, if you get a chance to hear him, grab it.

This book is the only one, certainly in English that I know of, which deals with events surrounding the events at Przemsyl in 1914-1915. Today Przemsyl is on the Polish-Ukrainian border. In WWI, it was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Galicia, and the fortress was intended as a bulwark against the Russians. The borders of Galicia, where it lay, were rightly considered to be indefensible, so the defensive plan was to fall back to Przemsyl and the defensive line of the River San. Przemsyl would have been known by its German name of Premissel, which is at least easier to say, unless you are Polish.

Indeed, the word fortress is a misnomer because, like Verdun, it is a complex of major forts and small outposts surrounding the town. Some of outposts lie today in the Ukraine. However, unlike Verdun, it was never modernised either in terms of its armaments or in terms of reinforcing the structure to withstand modern artillery. The saving grace turned out to be that the Russians did not have the heavy siege mortars like those which the Germans deployed against the forts at Verdun and Liege. Indeed, many of those siege mortars will have been produced in Austro-Hungary at the Skoda armaments factories at Pils.

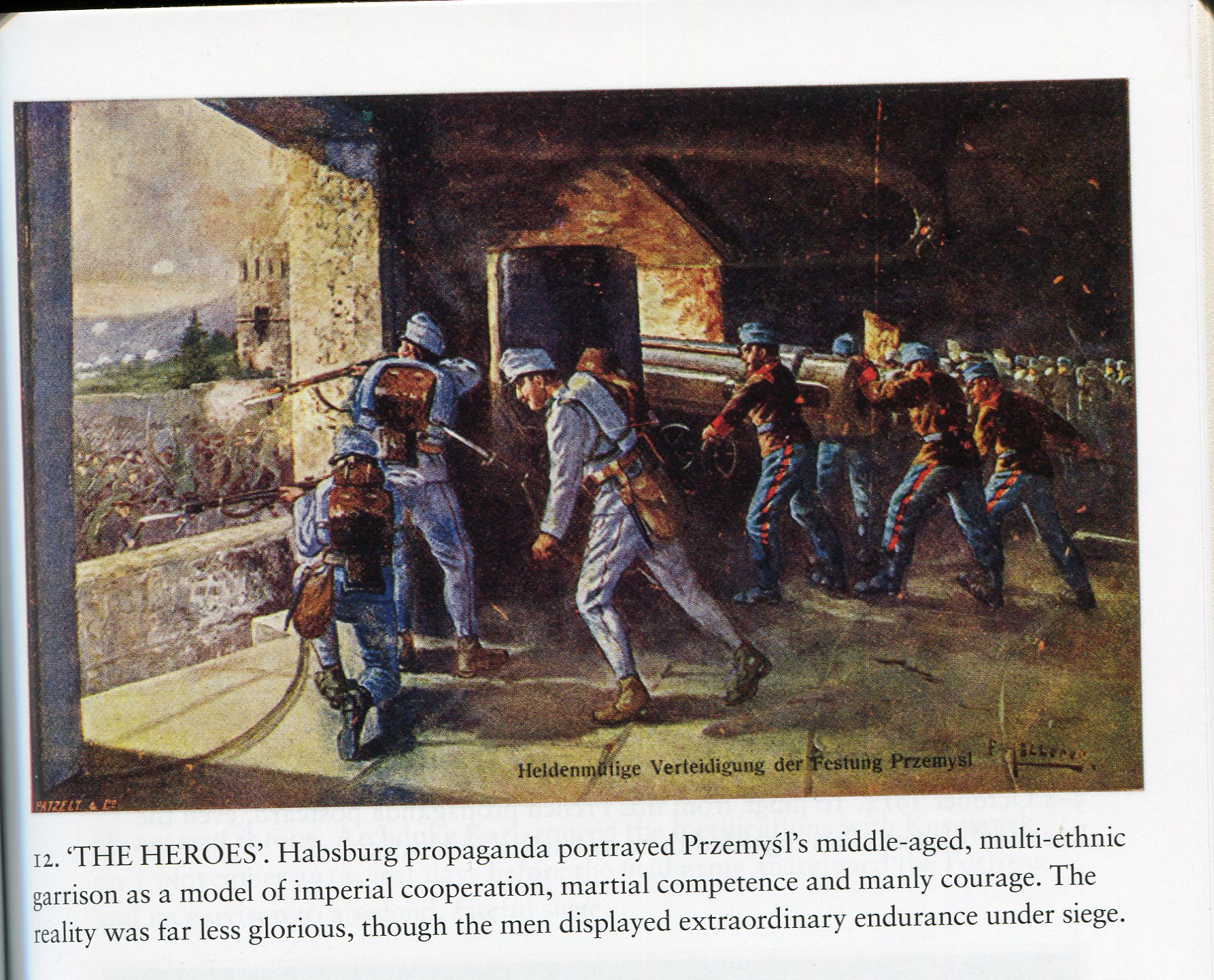

There were two episodes of siege, as the fortress held out as the Hapsburg armies retreated west in the face of the Russian advance, and then with the ebb and flow, it was relieved and besieged for a second time, more effectively and finally. The siege ended because of the garrison running out of food, notwithstanding having eaten most of the horses, and having to surrender. The Austrians maintained that it was the only siege in WWI where the defenders were not defeated, but if you are starved out and have to surrender, that is hardly a triumph.

As well as the casualties in defending the fortress itself, there were huge casualties suffered in the field armies fighting in Galicia, trying to fight the Russians and/or to free the fortress. There was associated fighting in the Carpathian Mountains over the winter of 1914-1915, again with huge losses on both sides. All in all, the major losses sustained by the Austro-Hungarians and the Russians at this early stage in the war greatly limited their actions thereafter. Austro-Hungary eventually needed help from Germany. Russia was not able to push westwards into Austria and Germany, as it could have done, but for the siege at Przemsyl.

The book deals with the bizarre structure of the Austro-Hungarian army, with its 11 languages and innumerable dialects. The Jewish soldiers were an important resource in this regard, as they will have spoken Yiddish, as well as the local language of the area where they were from. Yiddish is a German dialect, so German-speaking officers used the Jewish soldiers as translators into, say, Polish or Slovak or Hungarian or whatever was the language of that regiment.

As regards the local populations, there were murders and pillaging especially against the Ruthenes, by both sides. Ruthenes were distinguished by their religion of Greek Catholic Christianity. The Austro-Hungarians saw them as being sympathetic to the Russians and the Russians saw them as being renegades who were not “proper” Russian Orthodox Christians. The Ruthene population has largely emigrated from this region today.

On You Tube there are video interviews with local Polish experts, in English, which show the remains of the forts and help to explain what happened. They are a useful adjunct to the book. Professor Watson has been to see the forts and liaise with local Polish experts on a number of occasions. One of the videos is at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=856nOROd5ig

My personal hobbyhorse, not only with WWI but also European history generally, is the way that Russia is ignored. It is, after all, the biggest country in the world. This book certainly helps to correct that by bringing to attention this virtually unknown, but very important, episode of WWI.

The author has also written a book on Germany and Austro-Hungary in WWI, which is huge but with his easy-going writing style, it may well be worth trying. (Having now read it, the book is indeed very digestible in spite of its length).