The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have articles by Terry Jackson on the US Navy in WWI, and an article on the factor that, apparently, killed lots of soldiers in WWI – mallard ducks. Really?

Zoom talk

There were will a Zoom talk at 8pm on Friday 9th October on Gordon Shephard – the man who never was? by Trevor. (Strictly speaking, this is for the Lancs and Cheshire branch but obviously anyone can join the talk as it is on the internet).

The details of how to connect are as follows. You can either click on the link and it will take you through to Zoom and download Zoom software and take you into the meeting, though you will need to enter the passcode when asked. Otherwise, you can download Zoom software and set up your own free account. You then use the meeting ID and then the passcode to enter the meeting. Doors open at 7.45pm! Click on “Join with computer audio” to be able to listen. You can click on “Join with computer video” if you wish to be seen!

Time: Oct 9, 2020 7:45 PM

Join Zoom Meeting:

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81096652185?pwd=QlEycW9xbStJSUI2NDJ5bTczV0tGQT09

Meeting ID: 810 9665 2185

Passcode: 605121

The US Navy in World War One

Terry Jackson

During World War One, the US Navy inflicted few losses on the German Navy - one definite U-boat plus others possibly mined in the huge North Sea barrage laid in part by the US Navy between Scotland and Norway. Also, few major ships were lost to enemy action - one armoured cruiser and two destroyers. However, the large and still expanding US Navy came to play an important role in the Atlantic and Western European waters, as well as the Mediterranean after the declaration of war in April 1917.

Most of the battlefleet stayed in American waters because of the shortage of fuel oil in Britain, but five coal-burning dreadnoughts served with the British Grand Fleet as the 6th Battle Squadron (US Battleship Division 9) tipping the balance of power against the German High Seas Fleet even further in favour of the Allies. They were also present at the surrender of the German Fleet. Other dreadnoughts (Battleship Division 6) were based at Berehaven, Bantry Bay, Southwest Ireland to counter any break-out by German battlecruisers to attack US troop convoys. Some of the pre-dreadnoughts and armoured cruisers were employed as convoy escorts between 1917-18 both along the coasts of the Americas and in the Atlantic.

All three scout cruisers of the 'Chester' class together with some old gunboats and destroyers spent part of 1917-18 based at Gibraltar on convoy escort duties in the Atlantic approaches. The destroyers were part of 36 United States destroyers that reached European waters in 1917-18. Many of them were based at Queenstown*, Ireland, St Nazaire and Brest, France. Their main duties were patrol and convoy escort, especially the protection of US troopship convoys. Some of the 'K' class submarines were based in the Azores and 'L' class at Berehaven, Bantry Bay, Ireland on anti-U-boat patrols 1917-18.

In 1917, the programme of large ship construction was suspended to concentrate on destroyers (including the large 'flush decker' classes’, 50 of which ended up in the Royal Navy in 1940), submarine-chasers, submarines, and merchantmen to help replace the tremendous losses due to unrestricted U-boat attacks. Some of the destroyers and especially the sub-chasers were deployed in the Mediterranean, patrolling the Otranto Barrage designed to keep German and Austrian U-boats locked up in the Adriatic Sea.

A month after the United States declared war, the first American warships arrived in Europe on 4 May 1917. The Germans had resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1917, leading to more than 800 Allied ships being sunk in a matter of months. Without escorts, these ships served as easy prey for the Germans. This warfare had reduced British grain stores to a critical three week supply. The Royal Navy urgently requested more destroyers for hunting submarines.

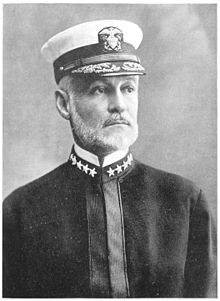

The destroyers’ arrival was due in part to the presence in England of an American naval mission headed by Vice Admiral. William  Sims (photo left). A few years before as Capt. Sims, he was President of the Naval War College at Newport. Appointed by the first Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), William Benson, together they anticipated a transatlantic naval war involving new challenges and technology. Ashore and in exercises of the “War College Afloat” they studied the role of the Navy in modern war.

Sims (photo left). A few years before as Capt. Sims, he was President of the Naval War College at Newport. Appointed by the first Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), William Benson, together they anticipated a transatlantic naval war involving new challenges and technology. Ashore and in exercises of the “War College Afloat” they studied the role of the Navy in modern war.

By 1917, Benson (photo left below) anticipated a naval campaign in European waters that would require a naval headquarters in England. Sims, with established reputation throughout the Navy, proved the ideal officer for that mission. He travelled to London under an assumed name, in civilian guise, arriving on 2 April 1917 with the intention of establishing direct contact between the United States Chief of Naval Operations, the Royal Navy, and other Allied naval forces.

By establishing an office in England called the “London Flagship,” Sims and a select staff of officers and expatriate American specialists evaluated and passed Allied naval communications and intelligence to the Department of the Navy. Sims and his staff promoted American naval opinions when reviewing strategy with the British Admiralty. They challenged the Royal Navy’s anti- submarine method and insisted that supply ships should sail in protected convoys.

A trial convoy formed on 10 May at Gibraltar, and sailed to England without loss. The second escorted convoy, bound for England from Virginia, also arrived undamaged. After that, all supply and troop shipping was required to sail in convoys. By mid-June, the five American  destroyers were escorting groups of arriving merchant ships into harbour. The convoy strategy overcame the German unrestricted submarine warfare campaign.

destroyers were escorting groups of arriving merchant ships into harbour. The convoy strategy overcame the German unrestricted submarine warfare campaign.

In the first month of American involvement in World War I, the US Navy changed the strategic balance, not with its growing fleet, or daring operations, but through sound strategic thinking. The convoy system secured the passage of the American Expeditionary Forces to France along with vital supplies for all the Allies. America was becoming a world power with a first class navy.

German and British naval policies made it difficult for the United States to remain neutral between 1914 and 1917. However, the intermittent German employment of unrestricted submarine warfare posed the severest challenge because of the inability of a small submarine to observe traditional prize rules. Disputes over enforcement of the British blockade could usually be settled by legal means in a prize court. German actions, in contrast, were final and could result in loss of life. The ship had been sunk, and - given the geographical realities of the North Atlantic - often in conditions hazardous to passengers.

On 4 February 1915, Germany declared the waters around the British Isles to be a war zone in which ships, even those flying the flags of neutral nations and their passengers, would be at risk. America insisted on the right of its citizens to travel unmolested. A series of German attacks resulted in strong American protests and temporary modifications of German naval actions. The most famous incident was the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1915, after the German government had published a warning in the New York press directed at residents of neutral nations sailing in ships flying enemy flags. There were 128 United States citizens among the 1,200 lives lost. In the face of the press and political storm that followed, the German government drew back and ordered submarines not to sink large liners, even those that flew enemy flags. This incident created a pattern reflecting the tug of war within the German government between those elements in the military anxious to exploit an effective weapon, and those seeking to minimize damage to relations with a powerful neutral like the United States.

There was another serious incident in March 1916, shortly after the Germans embarked on what could be called a “sharpened”  submarine offensive. On 24 March, the cross channel steamer Sussex (photo left) was torpedoed without warning and severely damaged; American citizens were among the casualties. Although the Germans denied responsibility for the incident, the protest by the United States government was sufficiently strong to bring about the so-called “Sussex pledge” on 4 May. German submarines would attack merchant ships only under prize or cruiser rules, not without warning. It was not until 1917 that a very few American flagged ships came under direct German attack, and some American lives were lost in them. Between 1 January 1915 and 31 January 1917, there were only three American fatalities.

submarine offensive. On 24 March, the cross channel steamer Sussex (photo left) was torpedoed without warning and severely damaged; American citizens were among the casualties. Although the Germans denied responsibility for the incident, the protest by the United States government was sufficiently strong to bring about the so-called “Sussex pledge” on 4 May. German submarines would attack merchant ships only under prize or cruiser rules, not without warning. It was not until 1917 that a very few American flagged ships came under direct German attack, and some American lives were lost in them. Between 1 January 1915 and 31 January 1917, there were only three American fatalities.

Germany’s failure to achieve favourable results in the Battle of Jutland, the long stalemate on land, and German naval assurances that unrestricted submarine warfare would force the British to make peace within a few months brought mounting pressure on the German government to sanction the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. The pressure was strong enough that, at the Schloss Pless Conference on 9 January 1917, it was decided to commence unrestricted submarine warfare as of 1 February. President Wilson responded by breaking diplomatic relations with Germany on 3 February. However, there was no state of war until German submarines sunk a number of American flagged ships in March. In at least three cases - the Vigilancia (photo below), City of Memphis and tanker Illinois - President Wilson considered German actions  as “overt” acts of war, for they involved ships clearly identified as American. In some cases, ships were westbound in ballast, so there could be no question of contraband cargo. It is debatable how much weight Wilson gave to these sinkings in making his final decision to ask Congress to declare war against Germany in April 1917. Nevertheless, the clear offensive nature of these acts and lack of ambiguity - such as Americans traveling under a belligerent flag - provided a powerful justification for action by Congress.

as “overt” acts of war, for they involved ships clearly identified as American. In some cases, ships were westbound in ballast, so there could be no question of contraband cargo. It is debatable how much weight Wilson gave to these sinkings in making his final decision to ask Congress to declare war against Germany in April 1917. Nevertheless, the clear offensive nature of these acts and lack of ambiguity - such as Americans traveling under a belligerent flag - provided a powerful justification for action by Congress.

The United States Navy embarked on a major building programme, which was approved by Congress in August 1916. New construction over a three-year period was to include ten battleships, six battle cruisers, ten scout cruisers, fifty destroyers, and sixty-seven submarines. It was, however, a fleet destined for a major naval encounter, which did not reflect the necessities of the naval war in Europe. The Navy at the time had only forty-seven destroyers in commission, the type of warship most needed in the struggle against submarines. Upon entering the war the Navy suspended the 1916 program and prioritised the construction of destroyers, building 273 of these ships. Few of these destroyers, however, ever entered wartime service.

Rear Admiral William Sowden Sims who had been dispatched to discuss possible cooperation with the British even before the United States formally entered the war, sought to convince the American government that the Allies desperately needed anti-submarine craft - preferably destroyers, but in practice any suitable craft was needed. This meant overcoming the concerns of the Chief of Naval Operations, Rear Admiral William Shepherd Benson saying that the loan of destroyers to the British would leave the American battle fleet unbalanced and not ready for future possible fleet action. Fortunately, the American government realized that the decisive theatre of war would be European waters, where destroyers, not battleships, were needed.

The first tangible naval assistance to the British came in the form of six destroyers of the Eighth Division, Destroyer Force, Atlantic Fleet, which arrived at Queenstown, on the southern coast of Ireland on 4 May 1917.They were the first instalment of a planned destroyer force of thirty-six, a goal achieved by the end of August. The destroyer tenders Dixie and Melville (photo left) were also sent to support the destroyers. The American destroyers worked under the command of Vice Admiral  Sir Lewis Bayly, the British Commander in Chief, Coast of Ireland. Engaged first on patrol duties and subsequently as convoy escorts, these destroyers were probably the most important American contribution to the naval war. A large number of converted yachts later supplemented the destroyers’ anti-submarine work, particularly off the French coast. Admiral Sims was designated commander of US Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, and had headquarters in London, commonly known by its telegraphic address as “Simsadus”.

Sir Lewis Bayly, the British Commander in Chief, Coast of Ireland. Engaged first on patrol duties and subsequently as convoy escorts, these destroyers were probably the most important American contribution to the naval war. A large number of converted yachts later supplemented the destroyers’ anti-submarine work, particularly off the French coast. Admiral Sims was designated commander of US Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, and had headquarters in London, commonly known by its telegraphic address as “Simsadus”.

The Americans did not deviate from their strategic point of view that the centre of gravity of the naval war was on the other side of the Atlantic. They might have been tempted to do so in the summer of 1918 when the German Navy sent large submarines to operate off the North American coast. The six U-cruisers eventually achieved a number of successes between May and October 1918, sinking ninety-three ships, more than half were American, but almost two-thirds were either sailing craft or small fishing vessels.

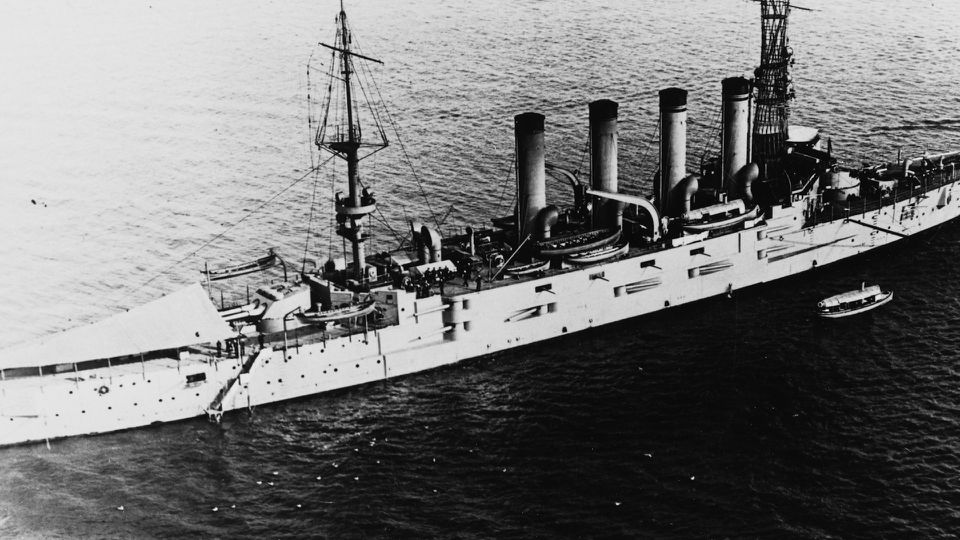

Convoys were for the most part unscathed. The most notable event was the sinking in July of the large armoured cruiser San Diego (photo left), sunk by a mine off Fire Island, near New York harbour. This demonstrated that the war had come to America's  doorstep. Indeed, there was even a partial blackout of New York City for a period of time. Importantly, the US Navy did not recall forces from European waters, and reassured America's Allies that this policy would not change. Furthermore, the German Navy was unenthusiastic about these operations. The limited number of large submarines and the long transit times involved meant operations off the American coast were uneconomic compared to operations in European waters.

doorstep. Indeed, there was even a partial blackout of New York City for a period of time. Importantly, the US Navy did not recall forces from European waters, and reassured America's Allies that this policy would not change. Furthermore, the German Navy was unenthusiastic about these operations. The limited number of large submarines and the long transit times involved meant operations off the American coast were uneconomic compared to operations in European waters.

The prospect of a major naval battle similar to Jutland in 1916 may have receded, but could not be completely discarded. If such a battle ensued, the American Navy was understandably anxious to contribute with its most powerful warships. Consequently, Battleship Division Nine of the Atlantic Fleet, consisting of four dreadnoughts under the command of Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman joined the Grand Fleet on 7 December 1917 and was designated Battle Squadron Six. The Americans, at British request, deliberately sent coal-powered battleships, as the British Isles had abundant sources of coal but had to import oil. The American dreadnoughts added to British naval superiority, although they never participated in the major fleet action for which they were designed. Later in the war, in September 1918, another three American dreadnoughts were stationed at Berehaven, Ireland, to counter a possible threat of German raiders in the North Atlantic. Once again, however, they never actually fired their guns in a hostile engagement.

The war against submarines required a different type of warship, one small and suited for escort or hunting duties. The American Navy developed craft commonly called “sub chasers”. These were 110-foot wood hulled vessels of seventy-five tons displacement, each armed with a three- inch gun and a few depth charges and powered by a gasoline engine. They were far less complex to build and operate than the larger craft and were therefore ideally suited for construction by smaller private yards. The Americans eventually built more than 400 of these ships. Unfortunately, they were far from ideal for their purpose as they were too slow to effectively escort convoys. Admiral Sims recognized their deficiencies, but made the best use of them possible. As he admitted to  a French naval officer, he did so simply “because we have them.” The Americans placed great hopes on an innovative method of hunting U-boats with hydrophones or sound detectors. The sub chasers in theory would operate in groups of three. Two chasers would locate the submerged submarine by cross bearings while the third would execute the “kill” with depth charges. The British had experimented with hydrophones with indifferent results and the Americans were also disappointed with this strategy. The experiments in underwater detection continued after the war, leading to the development of ASDIC (sonar), widely used in the Second World War. (Photo above – USS Texas, which is the only remaining dreadnought in the world).

a French naval officer, he did so simply “because we have them.” The Americans placed great hopes on an innovative method of hunting U-boats with hydrophones or sound detectors. The sub chasers in theory would operate in groups of three. Two chasers would locate the submerged submarine by cross bearings while the third would execute the “kill” with depth charges. The British had experimented with hydrophones with indifferent results and the Americans were also disappointed with this strategy. The experiments in underwater detection continued after the war, leading to the development of ASDIC (sonar), widely used in the Second World War. (Photo above – USS Texas, which is the only remaining dreadnought in the world).

The number of sub chasers in European waters steadily increased, as did the areas that they covered; by the end of the war, there were over one hundred in use. One squadron of thirty-six chasers operated from Plymouth in northern waters. Another group of chasers operated in the Strait of Otranto at the entrance to the Adriatic. This was a natural choke point through which Austrian and German submarines, operating from their bases at Pola and the Gulf of Cattaro, had to pass in order to reach the Mediterranean. The British, French and Italians were attempting to close this passage to submarines through a constantly expanding mine net barrage (the Otranto Barrage) patrolled by drifters and destroyers as ‘chasers’. Unfortunately, while the theory was fine, results were disappointing. The war ended without any chasers destroying a single submarine. The barrage was credited with two submarine sinkings: one submarine was ensnared in a net, and one was sunk by a mine.

The American effort in naval aviation was at least somewhat more successful than the Otranto Barrage. The rapid development of aviation was one of the notable features of the war, and the US Navy exploited its potential. The US Naval Air Service began operations at the British air station at Killingholme, near the mouth of the Humber, in July 1918 and eventually established four seaplane bases and a kite balloon station in Ireland. In France, there were six seaplane stations, three dirigible stations, and two kite balloon stations. Additionally, there was a large assembly and repair base at Pauillac, near Bordeaux, under construction at the time of the Armistice. In Italy there were another two seaplane stations on the Adriatic. Naturally this growth took time and accelerated in the closing months of the war. The numbers by then were impressive: 2,500 officers, 22,000 men, and over 400 aircraft. The Navy relied primarily on foreign-designed and foreign-built aircraft.

The lack of suitable aircraft slowed the development of a Navy and Marine “Northern Bombing Group” of land planes in northern France, whose mission was to bomb German submarine bases on the Belgian coast. The range of aircraft over the high seas was still relatively limited, but in coastal waters they were effective. This was especially true after German submarine commanders responded to the extension of the convoy system by moving closer inshore to attack ships after convoys had dispersed and ships headed to their final destinations. Because World War I aircraft could not carry a bomb load sufficient to sink a submarine, aircraft were perhaps most useful in harassing submarines and making it difficult for them to stalk ships on the surface or take up favourable firing positions. Naval use of aircraft therefore prevented losses rather than destroyed submarines.

The Navy also developed a more effective anti-submarine craft than the 110-foot chasers. These were the 200-foot, 430-ton “Eagle” Boats sometimes referred to as “Ford” Boats because they were built by the Ford Motor Company of Detroit. Over one hundred of these were ordered. Ford applied the industrial techniques of mass production to their construction when possible. A non-traditional ship builder like Ford, with yards on the Great Lakes (and thus far from the ocean) was a notable example of the industrial potential of the United States applied to the war effort. However, no ships were finished before the end of the war. The same techniques of mass production were applied to the building of standardized classes of cargo ships. One of the largest complexes of shipyards in the world was constructed on the undeveloped mud flats of Hog Island, near Philadelphia. There was also a large class of so-called “Lakers”; the “Lake” class of smaller freighters built in shipyards on the Great Lakes. Their size was limited by the necessity of passing through the Welland Canal in order to reach the high seas. Again, relatively few of these ships had entered service by the time of the Armistice.

The debate on instituting the convoy system began within the Royal Navy just as the United States entered the war. The British had already experimented with local systems. Extension of the convoy system proved to be slow, with the relatively ineffective patrol systems continuing at the same time. Convoys had their doubters in the American as well as British naval commands, and even the role of Admiral Sims, long credited with their adoption, is unclear. Nevertheless the United States was an invaluable source of anti-submarine craft, whether the craft were used on patrols or in convoys.

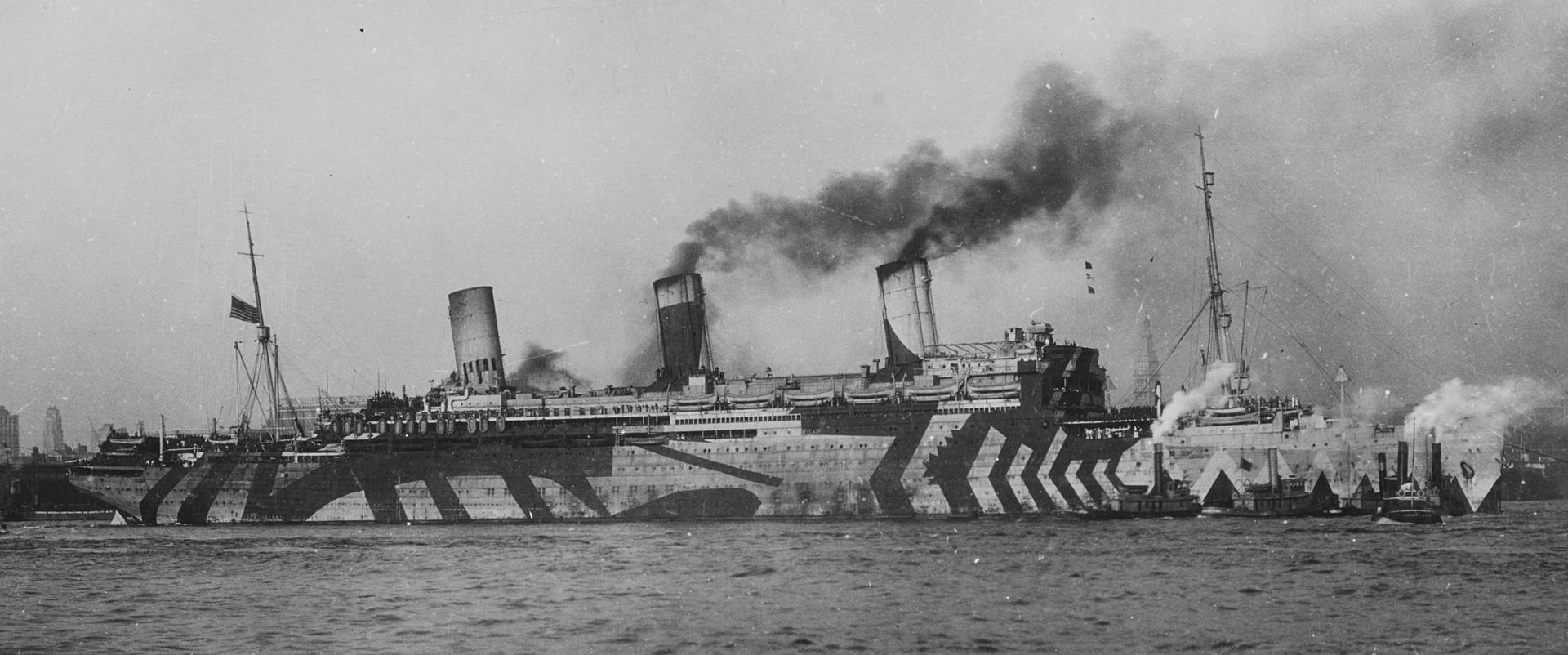

The American naval contribution to logistics was also great. By the end of the war there were over a million American soldiers on the Western Front, transported with only minor losses across the ocean. The American merchant marine did not have the large liners found in the European fleets, but the Americans were able to make use of British, French and Italian liners and eighteen  interned German liners, the most famous of which was the Hamburg-Amerika Line's Vaterland, renamed Leviathan (photo left). That ship on one record voyage carried 10,860 troops. American convoys, including troop convoys from New York were sent directly to the Bay of Biscay and French ports, and joined the existing British convoy system. The older warships of the Navy, notably cruisers or even gunboats dating from the Spanish-American War, may not have been of much use in a formal naval battle, but were useful enough for ocean convoy escorts. On the other side of the Atlantic an escort of four destroyers usually met a convoy at the 15th meridian. In January 1918, the Naval Overseas Transportation Service was established to run these movements, controlling as many as 375 ships at a time.

interned German liners, the most famous of which was the Hamburg-Amerika Line's Vaterland, renamed Leviathan (photo left). That ship on one record voyage carried 10,860 troops. American convoys, including troop convoys from New York were sent directly to the Bay of Biscay and French ports, and joined the existing British convoy system. The older warships of the Navy, notably cruisers or even gunboats dating from the Spanish-American War, may not have been of much use in a formal naval battle, but were useful enough for ocean convoy escorts. On the other side of the Atlantic an escort of four destroyers usually met a convoy at the 15th meridian. In January 1918, the Naval Overseas Transportation Service was established to run these movements, controlling as many as 375 ships at a time.

In the course of the war, both sides laid extensive mine fields in the North Sea. The largest and most ambitious was generally known as the “Northern Barrage.” The Americans were the primary movers behind the project, which involved a series of minefields across the North Sea, extending from the Orkneys to the Norwegian coast. The US Navy was responsible for laying Area A (130 miles), the longest of the three areas, while the British were responsible for the westernmost Area B (fifty miles) and the easternmost Area C (seventy miles). The idea was to close or hamper the exit of submarines north of the British Isles. The Americans employed a newly developed “antenna” mine, as opposed to the widely used “contact” mines. A special loading dock was prepared near the Norfolk Virginia Navy Yard for the fleet of over twenty “Lake” class cargo ships that transported the mines across the ocean. The American mine force was commanded by Rear Admiral Joseph Strauss. The formation charged with laying the mines, Mine Squadron One of the Atlantic Fleet, consisted of the old cruisers San Francisco and Baltimore and eight coastal steamers or merchant ships converted for mine laying. The American mine laying capabilities were greater than those of the British, with some ships laying over 5,500 mines in a four-hour period.

Consequently, they eventually joined the British in laying areas B and C. The Americans lay over 56,000 of the 70,000 mines eventually installed. The technical preparations for the project took considerable time. The British did not begin their mine laying until 3 March 1918, while the Americans did not begin until 8 June. The Americans had similar plans for the Adriatic and Mediterranean after the Northern barrage was completed, but the war ended before they could be implemented. The project was controversial. Certainly a few submarines - estimates are six - might have been sunk, but whether these results were commensurate with the immense effort and resources expended is debatable. Moreover, by the time the barrage was laid the convoy system had already been effective in decreasing the losses to submarines.

The US Navy in the First World War did not participate in any major action, and its role has been overshadowed by the hard fighting associated with the much larger military forces on land. Nevertheless, the Navy contributed significantly at a critical moment in muting the German submarine threat, and played an equally important role in assuring the logistical demands of the American Expeditionary Forces in France. By the end of the war, the United States had committed considerable naval and maritime forces to Europe. The time needed for those substantial forces sometimes seemed too slow to the hard pressed Allies. Nevertheless, the scale of the American effort became apparent in the final six months of the war. Much of this effort, such as the large building programs, was of potential importance and would likely have played a considerable role had the war lasted into 1919. The potential of American industrial strength was clear and foreshadowed the American naval program during the Second World War.

*In 1920, Queenstown reverted to its original name of Cobh (pronounced “cove”) which is near Cork, and Kingstown reverted to being Dun Laoghaire (pronounced Dunleary), near Dublin, and where US destroyers were also based in the later stages of WWI.

How a few ducks caused thousands of casualties in WWI?

A scientific paper published by American researchers in September castes new light on the effects that weather may have had on deaths in WWI, notably those caused by disease, especially the Spanish flu. To quote the paper (and I have edited it to make it easier to follow):

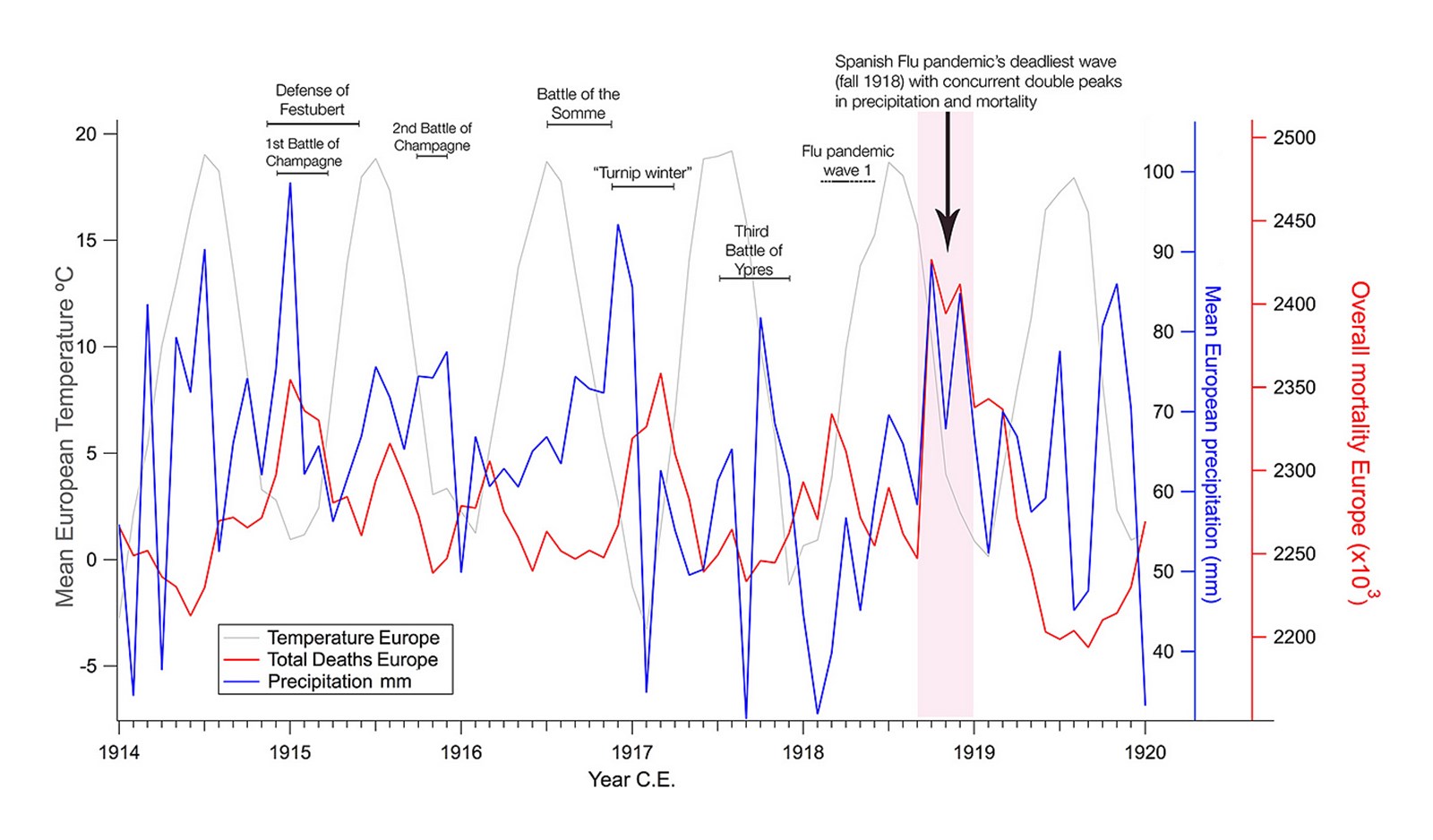

A new, high‐resolution climate record from Europe shows a once‐in‐a‐century climate anomaly that occurred during the years of World War I and the Spanish flu pandemic. Mortality data from all causes show increases in times of worsening weather, precipitation, and temperatures, a factor in many of the major battles of WWI, as well as a possible exacerbating factor for the virulence of the pandemic.

The data presented here show that extreme weather anomalies captured in the chemistry of glaciers and re-analysis records brought unusually strong influxes of cold marine air from the North Atlantic, primarily between 1915 and 1919, resulting in unusually heavy rainfall, and that they exacerbated total mortality across Europe, due to the interplay of environmental, ecological, epidemiological, and human factors. As we experience increasingly severe weather anomalies brought about by global climate change, and with the persistent seasonal recurrence of H1N1, the contribution of environmental change and human action to pandemic morbidity, mortality, and diffusion cannot be underestimated.

A century ago, in the autumn of 1918, the deadliest wave of the H1N1 influenza pandemic, known as the “Spanish Flu”, claimed tens of millions of victims. It marked the beginning of the end of several years of unprecedented mortality throughout Europe, due to the horrors of World War I (WWI), and an unusually extreme, multiyear climate anomaly that brought torrential rains to battlefields as well as urban areas. The inescapable muddy landscapes of the war remain a common theme of surviving WWI eyewitness accounts and photographs. Despite recent work on the impact of climate change on the spread of viral infections and overall mortality, the role of environmental changes in the WWI‐Spanish flu period remains under-examined. Here we present a new, high‐resolution climate record deduced from core samples from the high Alpine Monte Rosa (4,450 m a.m.s.l.) Colle Gnifetti (CG) glacier in the heart of Europe, indicating abnormally high influxes of North Atlantic marine air in the years 1914–1919. We evaluate the glacial and chemical data from this ice core with a detailed monthly record of overall mortality in Europe for the same period and monthly precipitation (rainfall) and temperature measurements. The multiyear, extreme anomaly described here, in several independent but concurring records, had a significant impact in setting the stage for the onset, spread, and mutation of the H1N1 pandemic, while also increasing all‐cause deaths due to widespread harvest failures and worsening battlefield conditions.

Total European mortality peaked three times, concurrently or following cooling temperatures, increasing precipitation (rainfall), and an extreme influx of cold marine air in winter 1915, 1916, and 1918. The glacial-chemical and instrumental records corroborate historical accounts of torrential precipitation on the battlefields of WWI—resulting in increased casualties due to drowning, exposure, pneumonia, and other infections—and its severity may have significantly altered the migration patterns of birds such as the mallard duck, the primary reservoir for the H1N1 avian influenza virus.

Graph showing the coincidence of WWI events, overall mortality in Europe,

Graph showing the coincidence of WWI events, overall mortality in Europe,

precipitation (rainfall) and average (mean) temperature

The highest increase of cold marine air influxes (an indicator of cold, wet weather) occurred in the summer–autumn of 1915 and winter of 1915–1916. Instrumental measurements of rainfall show an increase from the spring of 1915 to December 1916, with only a short interruption in July–August, and in December 1915. Extreme precipitation and winter conditions reached as far as Gallipoli (Turkey) in November 1915, famously affecting the ANZAC and British troops there, in one of the longest and deadliest campaigns of the war. Starting in January 1916, rainfall in Europe increased steadily throughout the year, with a peak in December 1916, coinciding with the battles of the Somme and Verdun, where the mud and water‐filled trenches and shell craters swallowed everything, from tanks, to horses and troops, becoming what eyewitnesses described as the “liquid grave” of the armies. Extended winter conditions delayed the start of the Chemin‐des‐Dames offensive until April 1917. They also caused widespread harvest failures, resulting in the “turnip winter” of 1916–1917, whereby the German population resorted to root vegetables for their diet, due to failed potato and cereal harvests and the allied blockade. After a brief respite, rain and cold returned again in the summer and autumn of 1917, with widespread flooding of the trenches in the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) in July–November, often bringing military operations to a standstill and substantially increasing casualties.

The first wave of H1N1 influenza in Europe emerged in the spring of 1918, most likely originating in the fall and winter of 1917, among allied troops that had arrived from Asia and had established their base camp near Boulogne. The combination of extremely high precipitation, the concentration of millions of troops on the battlefields, unsanitary conditions, and the use of chlorine gas as a chemical weapon have been cited as contributing factors to the mutation and emergence of the most lethal wave of the Spanish influenza pandemic in the fall and winter of 1918–1919.

So, where do ducks come into all this? Well, H1N1 is bird flu, as that is where the virus comes from. The article continues:

The coincidence between increased rainfall and mortality in this pandemic wave in late 1918 highlights the role of environmental conditions in a pandemic's morbidity and mortality, as already suggested in studies of recent H1N1 and other respiratory tract infections such as COVID‐19 in human populations especially in regions with extensive, long‐term air pollution such as Europe.

An additional exacerbating factor may have been the influence of the weather anomalies on established patterns of avian migration, similar to those documented for other species in response to modern, man-made climate change. Specifically, the migration of the mallard duck—one of the primary reservoirs of H1N1 avian influenza virus—may have been disrupted by the anomaly described here, resulting in increased presence of this species throughout Europe in the autumn of 1917 and 1918, in close proximity to both military and civilian populations, as well as domesticated animals. Studies of disruptions in mallard migration have shown that changes in the environment—at start point and throughout the journey—can affect overall movement and direction interrupting their normal migratory route. The transfer of H1N1 influenza virus from animals (avian and mammals) to humans occurs primarily via water sources contaminated with fecal droppings from infected birds. In autumn, the rate of influenza A viral infection can be as high as 60% in mallard populations, due to the exposure of “immunologically naïve” juveniles to the virus. Juveniles are especially prone to remain in the same area if their migration route is disrupted. Exposure of mammalian hosts (ie people and farm animals) to the same infected bodies of water where mallard ducks may have remained may explain connections to the current seasonal recurrence of H1N1 in human populations as shown in recent studies, suggesting that severe weather anomalies in 1917–1919 may have contributed to both the diffusion and mutation of the Spanish flu virus, as previous studies have suggested.

Well, there you have it. Unusually severe wet and cold weather over the period of WWI caused additional casualties, but probably with most effect when combined with the Spanish flu. We also know that being in close proximity to other people for a prolonged period can lead to the transmission of viruses. Huddling together in cold and wet weather, especially for those troops in trenches, or perhaps round a fire in other circumstances would have been an additional behavioural factor in the spread of a disease that is believed to have killed between 50 and 100 million lives. And the ducks are to blame!

Reference

American Geophysical Union, “The impact of a six-year climate anomaly on the ‘Spanish flu’ pandemic and WWI”, Alexander F Moore et al

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2020GH000277