The Dragon’s Voice

In this edition, we have an expanded book review on U-boats in WWI, the book being the PhD thesis of Joachim Schroder.

For obvious reasons, we have no face to face branch meetings for the foreseeable future, but there is a Zoom meeting (of the Stockport branch) coming up on Friday 14th May, which anyone can join in, and is on their website – www.landcwfa.org.uk.

Book Review

The Kaiser’s U-Boats

Joachim Schröder

Bernard & Graefe Verlag, Bonn

2003

Introduction

This book was a recommendation by Professor Alexander Watson. It was the PhD thesis of Dr Schröder and is based on his research in the German naval and other archives. Professor Watson states that it is much more difficult to find good contemporary information on U-boats as compared to surface ships, as obviously you could not write letters home to mum when serving in a U-boat. Hence, the paucity of good information on U-boat operations and their crews.

Before looking at the information in the book itself, it is perhaps worth having a look at naval terminology, as that reveals the attitudes of the time, and indeed more recently. In Royal Navy parlance, the surface vessels which they have are definitely “ships”. If you dare call a destroyer, or whatever, a “boat”, you will be politely corrected. A boat is a “ship’s boat”, that is a lifeboat or a launch, which belongs to a ship. Even in today’s Royal Navy, a submarine is referred to as a “boat”. Submarines were not regarded as “proper” naval vessels, hence in German as well, the submarine was a boat – an “underwater boat”, a U-boat.

In today’s Royal Navy, it would be unusual to find a senior officer who had not served in submarines at some stage of their career, such is their importance in the modern navy. However, in 1914 this would not have been the case in anybody’s navy. So, the senior officers of the day of whatever nation had no first-hand knowledge of submarines, and their capabilities and limitations.

The Book

In the context of the book, the disregard paid to submarines, as compared to surface ships, was a key feature of the German politico-military system of the era. At the start of WWI, one of the first steps of the German naval command was to close the U-boat training school. In 1912, the budget for U-boats was 20 million marks, compared to the cost of building one battlecruiser Derflinger in 1914, which was 56 million marks. The crew of the Derflinger was 1,200 men, more than the entire U-boat fleet, which had a total of 1,093 men. Even in 1917, the shipyards were preoccupied with building new surface ships and repairing those damaged at the Battle of Jutland, in preference to building U-boats. These surface ships would sit unused in harbour whilst the U-boats were at sea fighting the war. In many ways, the U-boat went from being the unloved maverick of the navy in 1914 to being, in some eyes, the saviour of Germany in 1917/18, through the so-called unrestricted U-boat campaign, albeit with slightly less than the full support of the high command.

One should say before going further that the U-boat campaigns cannot be considered in isolation. The key factor throughout the war was the naval blockade by the Royal Navy of neutral and enemy civilian ships on the high seas. This resulted in severe food shortages and starvation not only in Germany but Austro-Hungary and occupied Belgium and France. It was also the source of intense friction with the United States, which strongly objected to its maritime trade being disrupted. But how many British historians even mention the blockade?

Another key factor in the U-boat campaigns and their conduct was the British arming their merchant ships, so it became increasingly hazardous for the U-boats to surface (and allow the crew to leave the ship before they sank it), under the so-called “cruiser rules”, see below. In fact, throughout most of the war on most occasions U-boat captains surfaced, under the cruiser rules, to allow the crew of the ship in question to escape and to use the deck gun, rather than the few torpedoes which they carried.

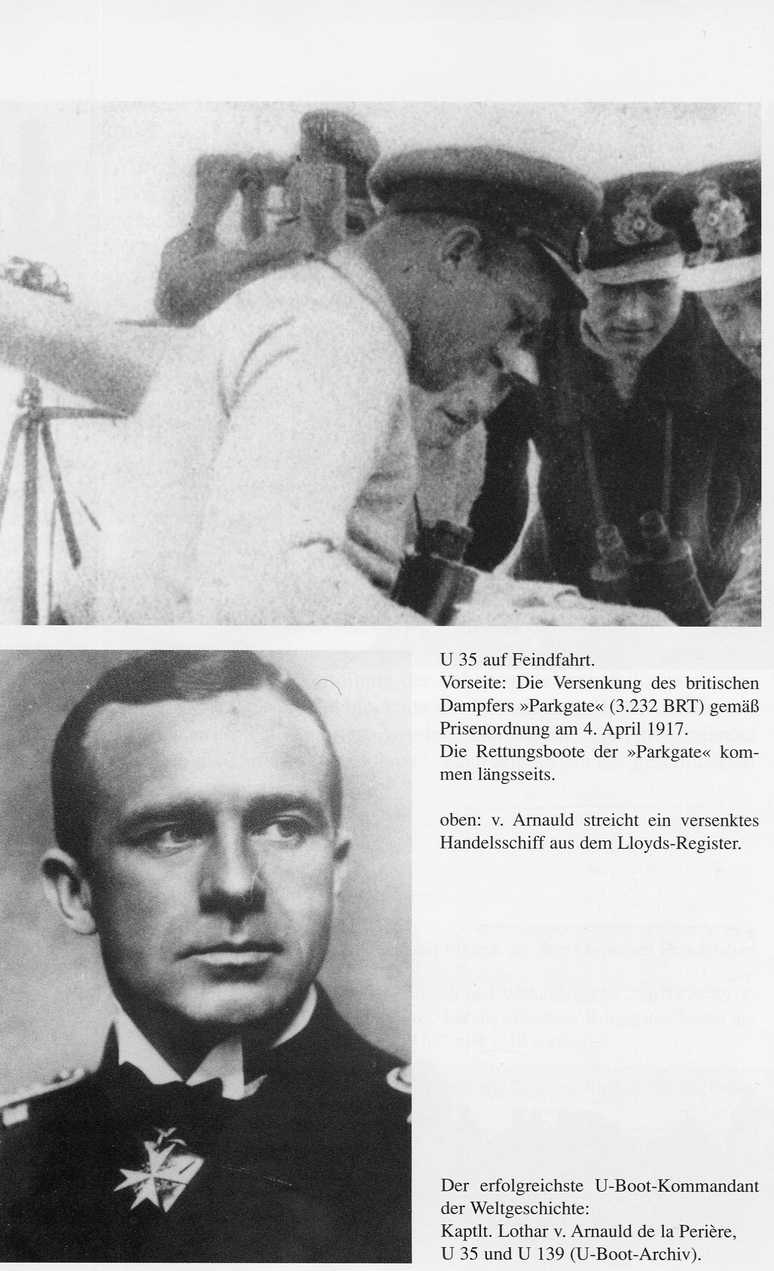

Photos below: the freighter Parkgate being sunk by U 35 according to the “cruiser” rules, ie by a surfaced U-boat, on 4th April 1917, and the crew alongside the U-boat in their lifeboats

To go back to the beginning of the war, in Spring 1914 Kapt Lt Blum calculated that to blockade the UK and cut off its sea trade would need 220 U-boats. At the outbreak of war, Germany had 10 high-seas U-boats, and 18 smaller ones for coastal defence. The highest monthly figure for all German U-boats in service in WWI was 140 of all types, in October 1917. Only a proportion of these would have been at sea at any one time. This includes all theatres – North Sea, Flanders coast, Adriatic, Baltic and the Dardanelles. The British greatly overestimated the number of U-boats deployed around Britain and Ireland, at one time estimating that there were no fewer than 500 U-boats deployed around the British coast alone. At one period in late 1915, First Sea Lord Jellicoe boasted that the anti-submarine measures deployed by the British had “defeated” the U-boats, at a time when the U-boats had in fact been withdrawn from around the British coast.

In 1914, the disruption of the troop transportation across the Channel would have been an obvious target. However, there was no overall plan by the German military to do so. The appeals by the army high command (OHL) to the U-boat leadership to do something were met with, at best, half-hearted attempts. The sporadic deployment was terminated late in 1914 as having been ineffective. To a certain extent, the navy regarded the movement of troops as an army problem, not primarily a naval one.

It is worth pointing out that even WWII submarines were, at best, only semi-submersibles, and that was even more the case in WWI. They had to run on the surface most of the time, as it was less slow than running submerged, and the battery power for running submerged was very limited. The batteries required charging from the combustion engines, which could only be done on the surface. Incidentally, there were U-boats in service at the start of WWI that had petrol engines. Diesel power quickly became the standard as the diesel engines became compact enough to put in even the smallest submarine, and was a lot safer for the crew.

One type of U-boat was small and only intended to defend the coast against attacks by enemy surface ships. This was the “UB” series, which had no deck gun and carried two torpedoes (though later versions carried more than that). Another was coastal minelayers – the “UC” series, which carried 12 mines, no torpedoes and had no deck gun. So, not all U-boats were capable of taking to the high seas to attack enemy ships. Indeed, the British concept at the start of the war for their submarines was that they existed to defend the navy’s surface ships from the enemy’s surface ships. A major issue was that WWI submarines were a lot slower than any navy’s surface ships and would have had difficulty keeping up with them.

(Photos above: top, Kapt Lt von Arnauld deletes a sunken merchant vessel from his copy of the Lloyds’ Register: below, another photo of him, as the most successful U-boat captain – Kapt Lt Lothar von Arnauld de la Perière, to give him his full title, wearing his Pour la Merité medal).

From 1916, Blyth in Northumberland was used as an RN submarine base, it being further south than Scapa Flow so as to give the submarines a head start in their journey to face the German fleet in the North Sea, ahead of the fast RN surface warships which would sail down from Scapa Flow.

Navies were obliged to use “cruiser rules” when dealing with merchant ships. These rules were indeed intended for cruisers, ie big surface ships. The idea was that the warship would tell the merchant ship to stop, send a boarding party to examine the ship’s cargo manifest and, if appropriate, tow the ship to the nearest port. If the ship was to be sunk, the crew were to be given time to board the lifeboats and given the course to the nearest land. The U-boats were bound by these rules, though no-one had ever thought of submarines when the rules were being created. One issue is that WWI U-boats are very small. How could a submarine tow a merchant ship to a port? In fact, there is a case quoted in the book of a U-boat doing just that, but clearly that was an exception.

However, the obvious issue is that the U-boat has to be on the surface to do all this. At the start of the war, no U-boats would have had a deck gun, ie an artillery piece which could be used when the U-boat was surfaced. This changed quickly, and bigger and better deck guns were installed as the war progressed. The ocean-going U-boats early on in WWI could only carry 6 torpedoes, but could carry a considerable number of shells for the deck gun, typically 300 rounds in the case of U-19, which was thought to be a better use of the limited space. So, the U-boats operated largely on the surface, and only late in the war increasingly went to torpedo attacks whilst submerged. Contrary to that trend was the introduction in 1917 of so-called “cruiser U-boats” which were bigger submarines that had bigger deck guns and were primarily intended to be submarines which attacked other ships on the surface. They were converted from large U-boats which were intended originally as transports and therefore a way of avoiding the Royal Navy blockade. They typically carried 18 torpedoes and 1672 rounds for two 105mm deck guns.

In comparison, at the start of WWI, the Royal Navy did have a submarine with a deck gun but they were not generally installed until 1915. I would add that the author attributes more British submarines being equipped with a deck gun than was in fact the case. The initial British view was that deck guns were only relevant for attacking merchant ships, as a surfaced submarine is not going to win a gun battle with a major warship. However, following the British experience in the Dardanelles in 1915, British practice followed the German with more installation of deck guns, and ultimately the development of “cruiser” submarines, intended primarily for surface engagements (Norman Friedman, British Submarines in Two World Wars).

As mentioned above, submarines in WWI (and WWII) were slower than surface warships, whether submerged or surfaced. Indeed, the liners used by the USA to bring their troops to Europe in 1917/18 were so fast, that if a U-boat did not see the ship coming, it had no chance of catching up with it. For example, U 23 had a top speed of 16 knots on the surface and 9 knots submerged, with a very limited range when submerged (50 nautical miles at 5 knots). Liners and mail boats would typically have top speeds of 24 knots or more.

Effective defence measures against U-boats developed late in the war. The convoy system worked well, though there were organisational issues, such as the slowest ship determining the speed, and the traffic congestion outside ports when a convoy of ships arrived all at the same time. The use of aircraft and airships enabled spotting of U-boats on the surface and possibly attacking them or directing surface warships, notably in coastal areas. In late 1917, the British and French constructed a mine and net barrage between Folkestone and Cap Gris Nez which effectively cut off the Channel even for transit by U-boats. In contrast, the megalomanic attempt to use 71,000 mines to create a barrage between Scotland and Norway was a disaster. The sea was too deep and the mines were unreliable. The author reckons that four U-boats were definitely lost to this barrage and possibly another two, at a time when 35 U-boats per month were transiting through this area.

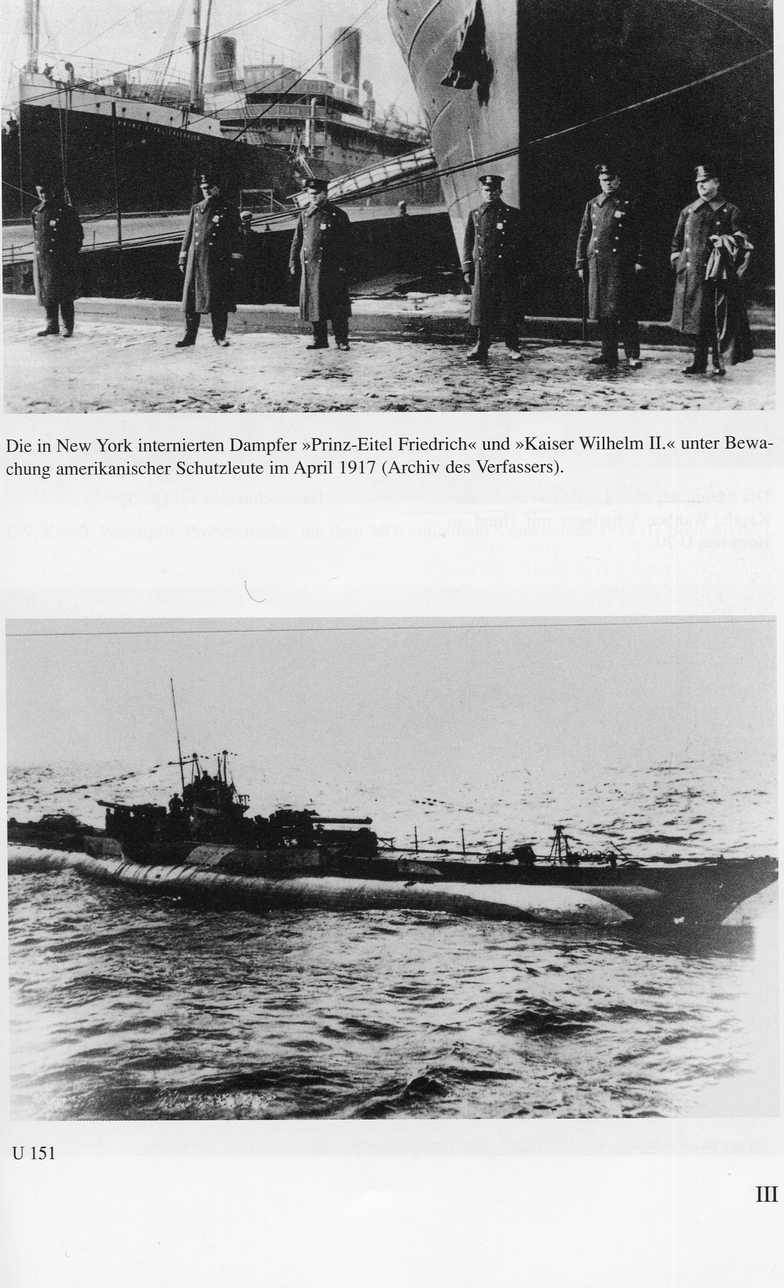

Photos above: top, two German liners interned in New York in April 1917 when the USA entered WWI; below, U 151, a cruiser U-boat with deck guns fore and aft of the conning tower.

The machinations inside the German regime concerning the so-called unrestricted U-boat campaign of 1917/18 are dealt with in detail by the author. The fear of the Kaiser and of Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg was that such a move would bring the USA into the war, which indeed it did. The leading proponent of the strategy was Ludendorff, who was of course an army general. Cooler heads believed that the strategy would not work. Ultimately, they were right. The increase in sinkings, before the effective defensive measures kicked in, was in fact mostly due to there simply being more U-boats (see Holger Afflerbach, On a Knife Edge). The rate-limiting step in a submarine war is finding target ships. In WWI, this meant being near ports, which left the U-boat more vulnerable to being spotted from the air, later in the war, and to attack by warships patrolling near the ports.

Technical advances through the war included better periscopes which elevated when needed, rather than being fixed, deck guns which were increased in calibre through the war, the introduction of more numerous “blow valves” on the flotation tanks, so that crash dives became possible, and elimination of the remaining petrol-engined boats. Throughout the war, the technology of the U-boat was improved. Indeed, an American admiral opined that the German U-boats were the most technically advanced of WWI.

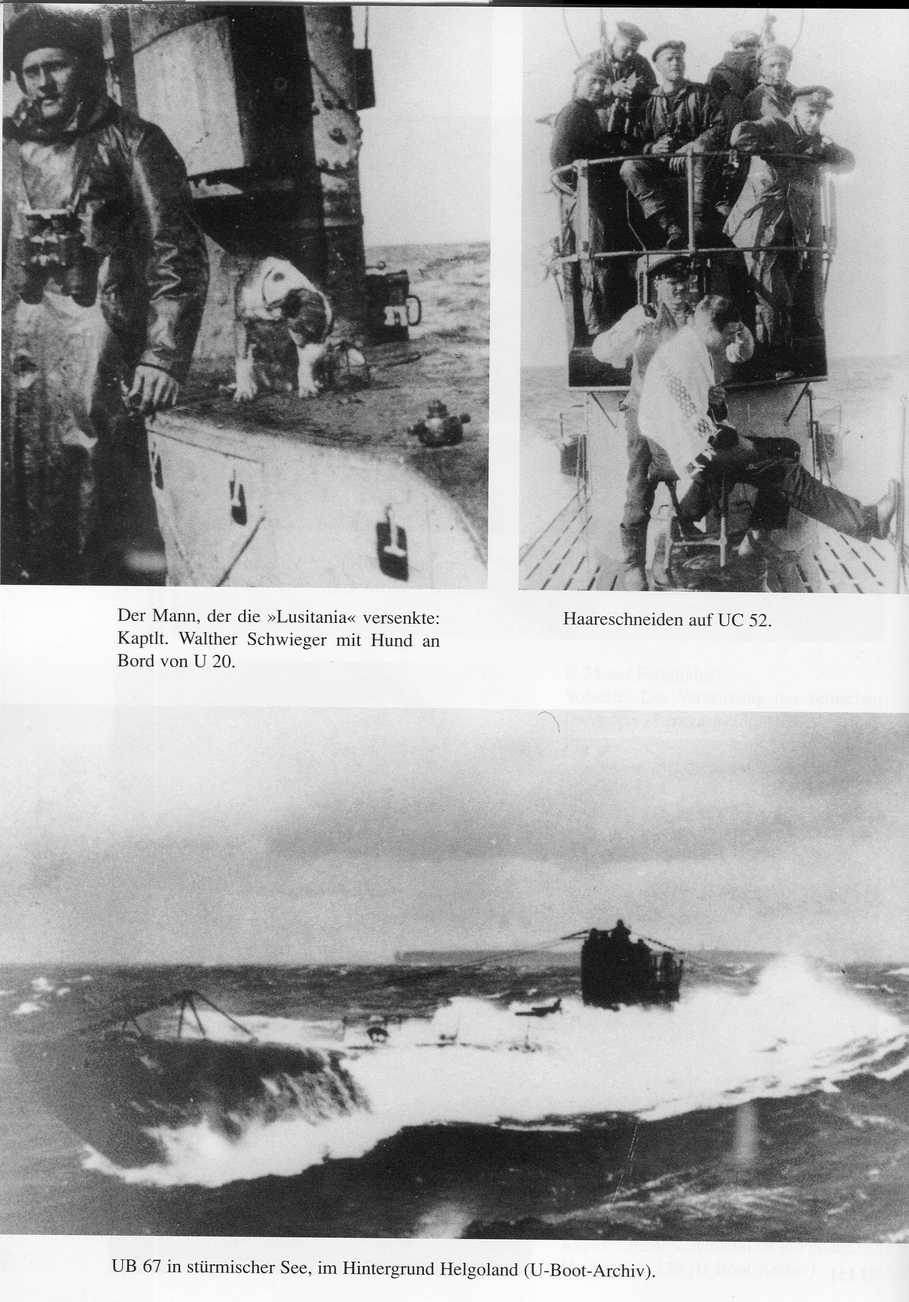

The case of the Lusitania is dealt with in detail. The ship had in fact been equipped in 1913 with gun mountings and ammunition stores. It was on the Admiralty list as a reserve auxiliary cruiser. Whether on the fateful journey there were guns hidden on deck cannot be proved one way or the other. She certainly carried ammunition – 4.2 million rounds of Remington rifle ammunition, 3,240 shell fuses, 46 tons of aluminium powder for explosive manufacture and 5,000 shrapnel shells, apparently transported without explosive charges. It is clear from the U-boat captain’s log that, on that day the 7th May 1915, he fired only a single torpedo. He states that he could not fire a second into a “crowd of people”.

However, he records that there was a second explosion on the ship. So, what was it on the Lusitania which caused the second explosion? The subsequent British propaganda claimed there were two torpedoes fired, but that seems to have been just propaganda. Another aspect of the Lusitania is why she sank so quickly. There were easily enough lifeboats to accommodate all on board, yet 1,198 people drowned, only a few miles from the major Royal Navy base at Queenstown (Cobh today). This indicates how dangerous to shipping submarines were, and that they generally operated around the coast rather than on the high seas. The political consequences of the sinking were, of course, enormous, and put paid to one version of the U-boat campaign.

Arabic was another propaganda cause celebre, and one that did cause the suspension of the 1915 U-boat offensive. On 19th August 1915, U 24 was off the South coast of Ireland about 60 sea miles off Kinsale Head. She had stopped the small steamer Dunsley, following the cruiser rules. U 24 was on the surface, had evacuated the crew of the Dunsley and had fatally damaged the ship with fire from the deck gun. U 24 was diving when another steamer was seen, which had changed course toward U 24 at high speed. This was the Arabic. She was neither showing a flag nor an identifiable name. Kapt Lt Schneide of U 24 recorded that he did not have time to surface again to fire a warning shot from the deck gun at Arabic, nor indeed could U 24 have outrun her. He believed the ship to be a 5,000 BRT freighter. U 24 turned in a semi-circle, fired one torpedo and hit the ship on the rear starboard. He did not find out what it was he had sunk until he returned to base. The political fallout of the Lusitania and Arabic was enormous, especially in the USA.

(Photos above: top left, the man who sank the “Lusitania”, Kapt Lt Walther Schweiger, with his dog on board U 20; top right, hair cutting on board UC 52, and you can see just how small the coastal minelayers were; bottom, a coastal boat, UB 67, in a stormy sea off Heligoland.)

The German ambassador telegraphed the foreign ministry to say that another case like the Arabic would result in the USA entering the war. There was therefore a suspension of the U-boat high seas offensive, to the extent that reports in the Norwegian press speculated that British counter measures had been incredibly successful and had resulted in the decreased number of sinkings.

It is worth noting the difficulties of seeing through a periscope. For example, British submarines were assigned to support an RN surface ship attack on Heligoland in 1914, which nearly resulted in the submarines attacking the RN ships. After that, the RN did not try direct support again and submarines were only used in areas where they could fire freely (Norman Friedman, British Submarines in Two World Wars).

The so-called Q ships were one British anti U-boat measure. Incidentally, the “Q” is for Queenstown, the RN base near Cork, today renamed Cobh. In spite of the picture painted by British propaganda, the author records only eight U-boats being sunk by Q ships, in contrast to the 30 Q ships sunk by U-boats. Ultimately, the acid test is that the tactic was not resurrected in WWII, whereas the use of convoys, which was highly effective, was indeed used in WWII.

In the unrestricted U-boat campaign of 1917/18, hospital ships were exempt, except for those sailing between England and France as it was strongly suspected that on the return journeys from England that they were being used to carry troops and war supplies. (One can tell from how high a ship sits in the water whether it is empty or laden.) This is another aspect of the U-boat campaign that results in much huffing and puffing from some British historians.

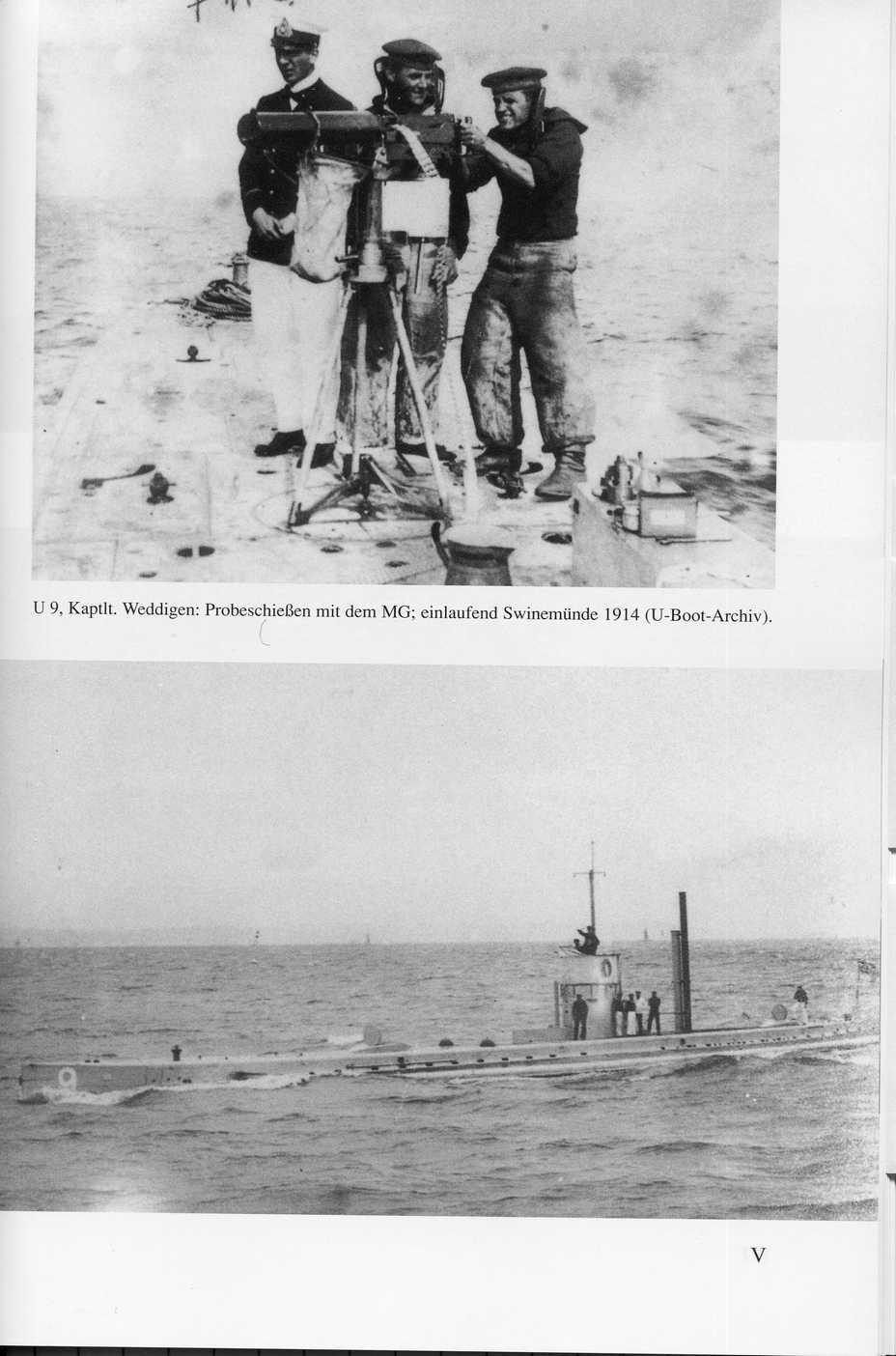

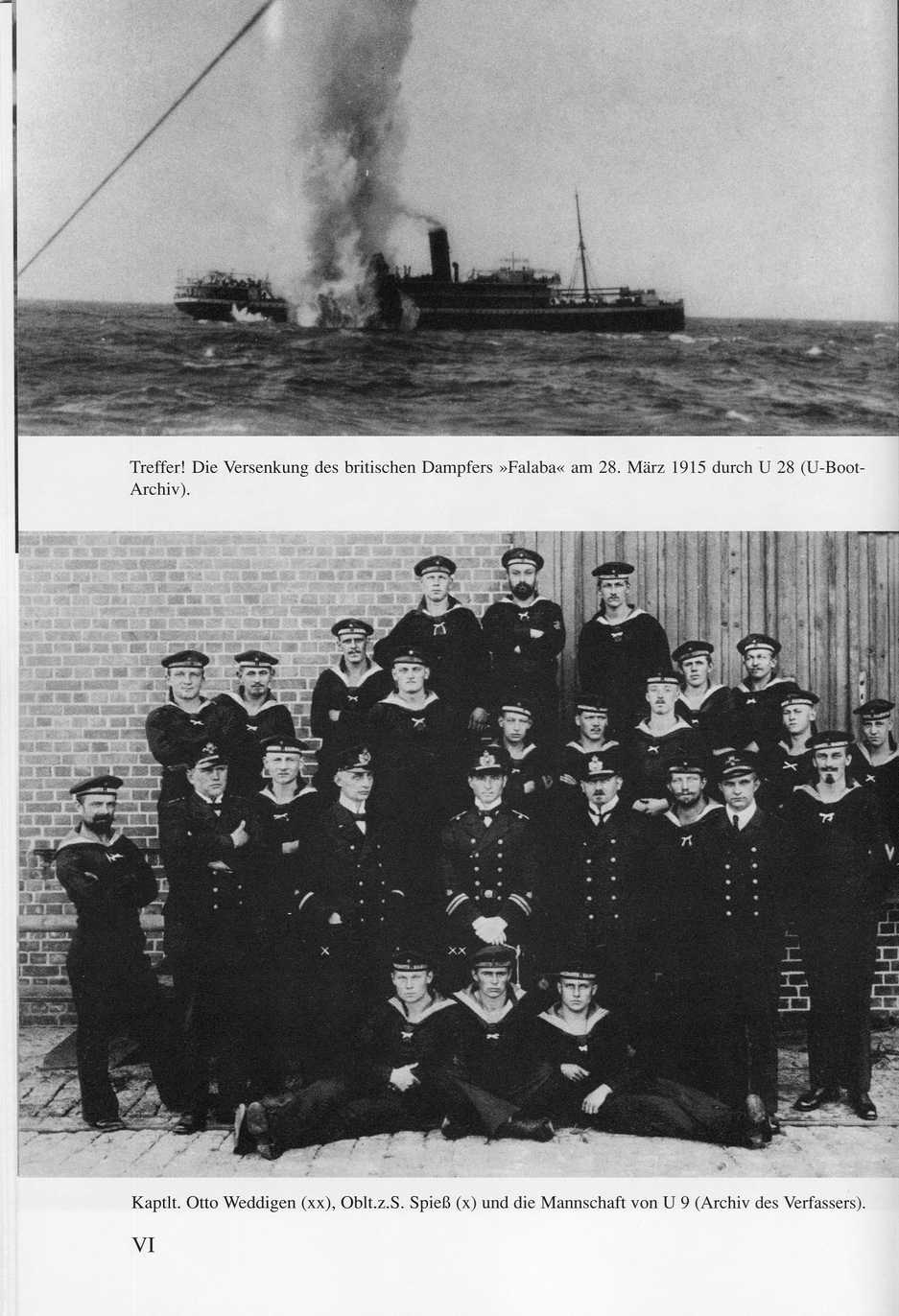

Photos above: top, on board U 9 with Kapt Lt Weddigen, testing the machine gun;

Bottom photo, U 9 at sea off Swinemunde, 1914.

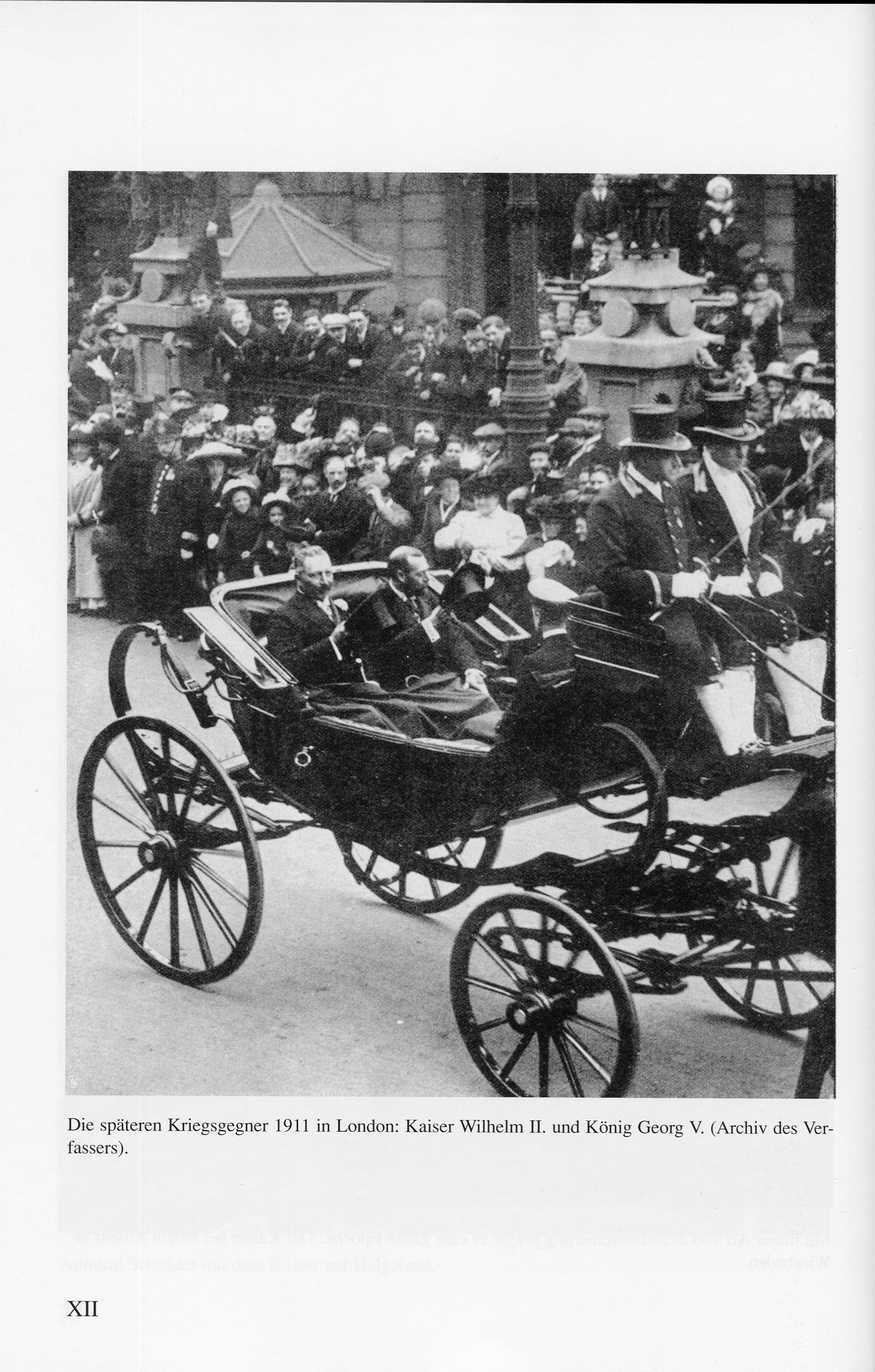

The German navy was indeed the Kaiser’s navy, as he retained command of it, in contrast to the army where there was an army high command, the OHL. Not until 1918, was there an equivalent body for the navy. Hence, the title of the book – they were indeed ultimately the Kaiser’s U-boats, though of course there was naval operational oversight. An interesting aspect of Kaiser Wilhelm is that he often made notes in English of meeting with political and military leaders, and there is an example in the book. He was, of course, as British or as German as his cousin in Buckingham Palace.

The various U-boat campaigns should be seen in the context of moves for a negotiated peace, from late 1916 onwards. The unrestricted campaign of 1917/18 was in many ways born out of frustration at the failed negotiations. It certainly soured attempts in late 1918 to produce a negotiated peace, with notably the sinking of yet another passenger ship, the RMS Leinster, off Dublin in October 1918 with the loss of 567 lives, making matters worse.

Photo above: the two cousins in London in 1911

The author sums up the situation as follows. Ultimately, the attempt to cut off the United Kingdom by attacking shipping using U-boats did not succeed. In 1917, the entry of the USA into WWI brought in more cargo ships, better protection for merchant ships by use of the US navy, and the US ship-building facilities. Convoys and the use of aircraft and airships were successful counter-measures, albeit late in the war.

The total number of U-boats deployed in all theatres was actually very small in comparison to the numbers of surface ships of any of the major players in WWI. An unrealistic assessment by the German politico-military leadership of the numbers of high seas U-boats available was a factor in launching the 1917/18 campaign.

The January 1917 decision for an unrestricted campaign went against the Clausewitz axiom of the primacy of policy over military action. The promise from the military of the campaign succeeding in five to six months was unrealistic in the extreme, but in keeping with the befuddled thinking that unleashed the campaign. The failure to achieve such a breakthrough led to damage to army and civilian moral in the summer of 1917.

The consequent abandonment of cruiser rules in the 1917/18 campaign, ie the U-boat surfacing and allowing the crew to escape before sinking the ship, was a major error, perhaps deciding the course of WWI.

Today’s view of WWI is that defence was in the ascendancy. The U-boat campaigns were one way round that problem enabling the enemy to be attacked at sea but also involving a lot of collateral casualties of neutral parties and civilians. Sticking to the cruiser rules, as the U-boats did for most of the war, enabled such collateral damage to be minimised.

Perhaps the greatest failure of the U-boat campaigns was that over the English Channel during WWI there were 24 million personnel movements, 3,221,992 sick and wounded soldiers evacuated, as well as 2.4 million animals, 553,829 vehicles, and 49 million tons of material transported. The U-campaigns did not seriously interfere with the conduct of WWI on the Western Front. In contrast, the British blockade which used surface ships seriously impacted on all the supplies to Germany, Austria and the occupied areas. Both campaigns ran against Kant’s postulate to avoid “bitter feelings” which would block the possibility of a negotiated peace. Ultimately, all wars end.

After the Versailles treaty, Germany was forbidden to own or build U-Boats. Indeed, the British tried to have all submarines banned, which did happen between 1922 and 1930, but without success in the long term, thanks to the views of its former allies.

Photos above: Hit! The sinking of the British steamer Falaba on 28th March 1915 by U 28, a photograph evidently taken on the surface from a U-boat; below, Kapt Lt Otto Weddigen and the crew from U 9

It should not be forgotten that, by surfacing, U-boats rescued ships’ crews and on occasions did not sink ships, because they were neutrals or because they did not believe the crew could make it to land in boats. The U-boat captains, given a choice, preferred to use cruiser rules as to quote one captain, Otto Weddingen, “We did not want to kill civilians but to destroy the ships, not the people”. At times during WWI, they disobeyed their instructions in order to do so.

Today, the submarine is a key weapon of navies, whether to launch nuclear weapons or to attack surface ships. From the end of WWII, submarines had the capability to remain submerged for the entirety of their deployment, as can be seen from the absence of deck guns today. One should never forget the dangers of submarines to their crews. As this review is written, we are a few days after the news that an Indonesian submarine has been lost with some 53 hands. The author refers to the Russian submarine Kursk where, even more grimly, some of the crew survived for a few days before their air ran out. All 118 hands were lost. In WWI, 178 U-boats were lost to enemy action, often with all the crew.

The merchant navy memorial at Tower Hill in London has just under 12,000 names from WWI. CWGC states that the total losses on merchant ships for WWI are 17,000. Compare these figures to the huge losses of any battle on the Western Front, or indeed any other front during WWI.

Photo above: Kaiser Wilhelm II and Prince Heinrich, his brother, inspecting an unnamed U-boat base in 1917

In contrast, the civilian deaths from the British blockade of the Central Powers are somewhere round half a million, but you will find its horrendous effects are often ignored in many books. Indeed, at the time the German government sought to play down the effects of the British blockade so as not to panic the public. Do not forget that the blockade did not end with WWI but continued until June 1919.

Conclusion

This book gives detailed coverage of the German navy’s U-boats, the campaigns, the politics and explodes various myths. There is an enormous amount of information in the book. There are 15 tables, the last one of which lists the fate of all German U-boats and their crews. Table 6 gives the number of U-boats at the front, on a month by month basis. There are 17 texts including extracts from a captain’s log, various orders issued by the U-boat command, diagrams of various types of U-boat and maps of the areas of operation. The book runs to 500 pages, some 90 pages of which are the appendices. The book is the authoritative work on WWI U-boats. I should add that it is in German.

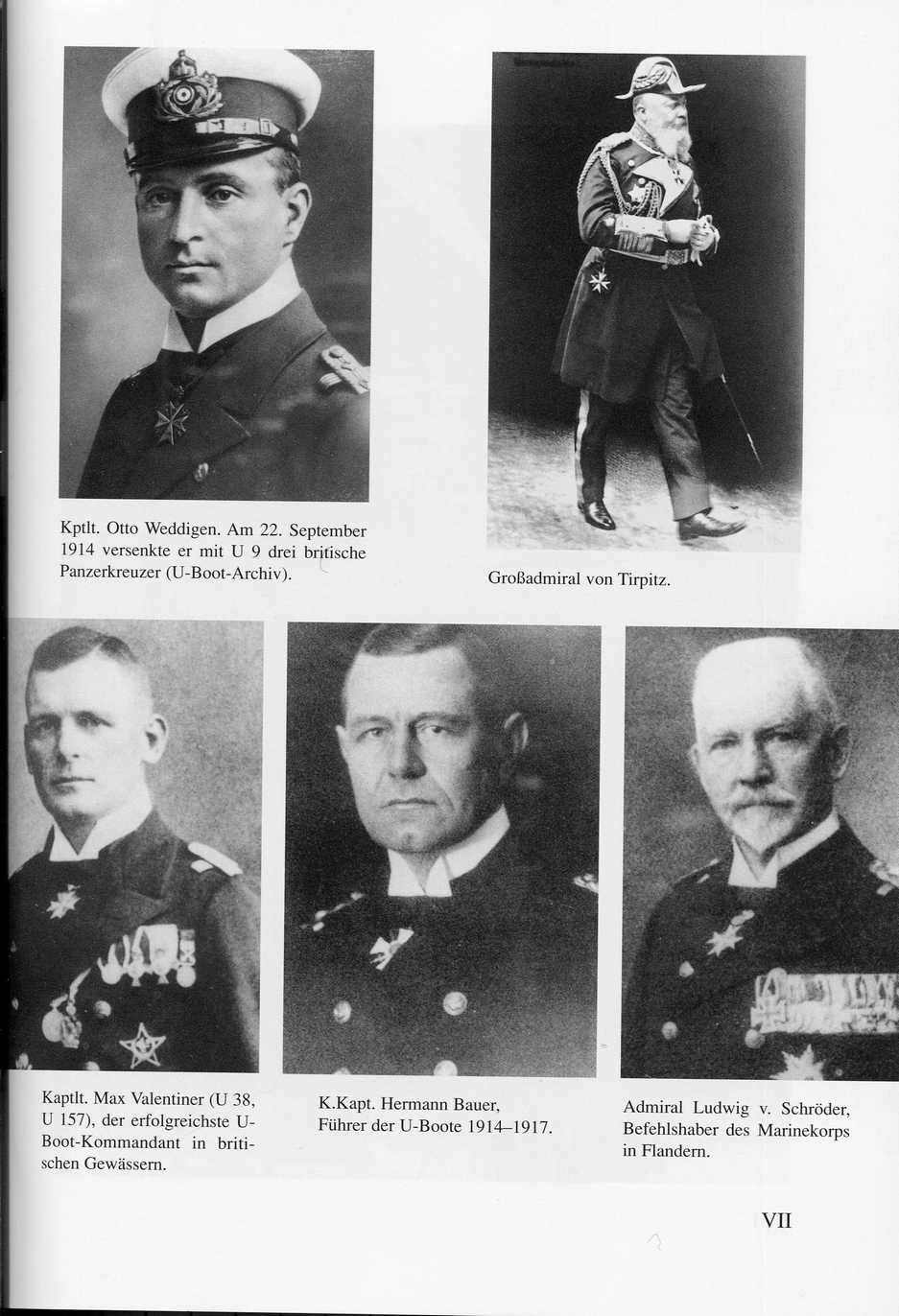

Photos: from top left, Otto Weddingen who sank three cruisers on 22nd September 1914, Admiral Tirpitz; second row, from the left, Kapt Lt Max Valentiner, the most successful U-boat captain in British waters, K Kapt Hermann Bauer, the head of the U-boat flotilla from 1914 to 1917, and Admiral Ludwig von Schroder the commander of the German navy in Flanders.