Memorials

- Should the battlefields be returned to civilian use?

This was a key issue – should the battlefields by kept as permanent memorials? This was the case in Verdun where the area was forested after the war and the villages were not rebuilt. There were plans for something similar in Picardy but the locals wanted to return to their villages and to continue farming.

- Strife with local authorities: too many memorials in France?

The British wanted to put up a large number of memorials in Northern France, but the number was whittled down, largely on economic grounds. The French could not afford memorials because they were stretched financially in reconstructing the devastated areas of their country. Their cemeteries therefore tend to be functional and huge. Also, do not forget that bureaucracy is a French word. So, there were disputes with French local authorities about British memorials which lead to ill feeling on both sides. For example, if you go to “Plug Street” (Ploegsteert) in Belgium there is a huge memorial on the edge of the village but in fact it commemorates a battle that took place over the border in France. The French authorities of the day would not let it be constructed in France, but the Belgians were quite happy to have it. We will look at some memorials in a moment.

- Memorials further afield – disappeared?

The Imperial War Museum has a design for a memorial to be erected in Salonika, in the design of a Lewis gun but there is no written record of it ever having been put in place, and no-one in Northern Greece or Republic of Northern Macedonia has heard of it (source: Alan Wakefield of the IWM). So, did it ever exist and, if so, where has it gone?

- Private memorials – who looks after them?

The big problem with private family memorials is – who looks after them when the generation that knew the soldiers passes away? We will see an example in a moment.

- Examples of memorials

The Ulster Tower on the Somme, funded by public subscriptions, opened 1921

The 10th Irish divn cross at Rabrovo in the Republic of Northern Macedonia, erected early 1920s

A CWGC cemetery today – Sucrerie at Colincamps on the Somme

Puchevillers CWGC cemetery during the war

Canadian memorial at Vimy – opened as late as 1936

Thiepval memorial on the Somme – it is in its third choice location, the first being astride a road, hence the central arch. Fabian Ware, head of the CWGC, was diplomatic and negotiated the current position on a dominant ridge. There is a joint French British cemetery, and the memorial always has French and British flags. It was originally intended to go across a road, hence the arch. It is in its third choice location. (Photo Philip Walker)

An isolated grave – of Major Willie Redmond MP of the 16th Irish Divn at Locre (Loker) in the Ypres area. It was originally in the garden of the convent but the convent was destroyed and the replacement is on the other side of the road. It is cared for by the CWGC whose cemetery is nearby. The Redmond family has declined to allow the grave to be moved into the cemetery.

The merchant navy memorial at Tower Hill, London ("For the Fallen", CWGC)

The Royal Navy memorial at Plymouth Hoe ("For the Fallen", CWGC)

Kosturino Ridge, Macedonia – believed to have a mass grave in the dip between the ridges of the 10th Irish Divn who were overrun in December 1915

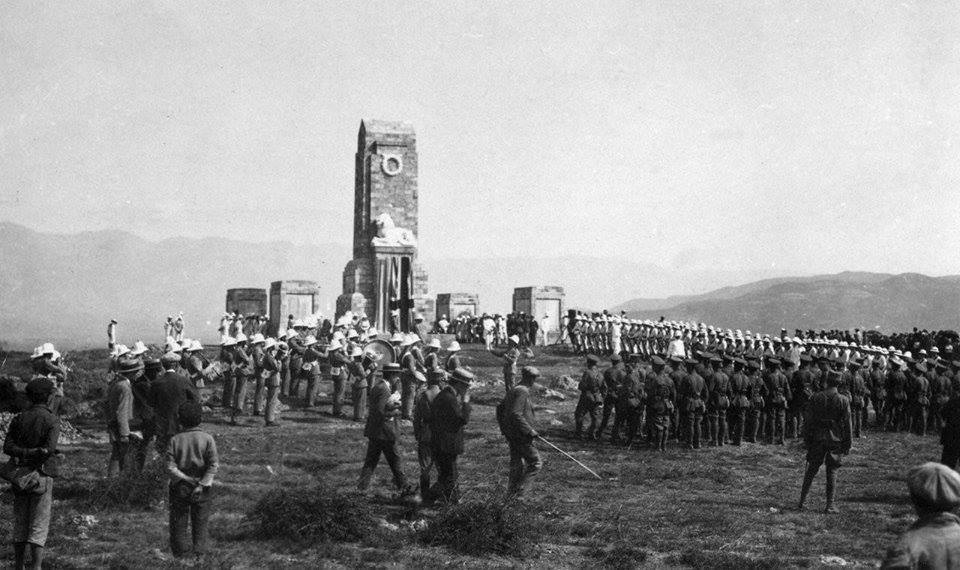

Opening of the Doiran memorial on the Greek – Macedonian border (CWGC)

WWI graves in the UK – Bodelwyddan churchyard, North Wales

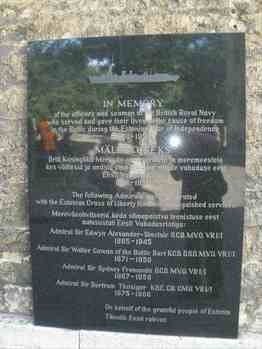

Memorial in Tallinn, Estonia, to the Royal Navy personnel who died in the Estonian War of Independence, 1918-1920 (Geoffrey Bennett)

Mount Edith Cavell near Jasper, Alberta, Canada. (Her name was apparently pronounced as “cavil”, with the emphasis on the first syllable, she was an administrator and she was reporting on German troop movements to the British, according to Stella Rimington in a BBC programme, but don’t worry about all this – just believe the myth!)

Theme – the finances

In 1914, the UK was a creditor. By 1918, the UK was a debtor and has been ever since. The position for the United States was the reverse. By 1918, Britain’s debt was 175% of GDP. After WWII, the debt was 240% of GDP – an even more expensive war. In 2018, British debt is 86% of GDP. (GDP is Gross Domestic Product, in effect a measure of the economy of the country).

Was the most important man in WWI JP Morgan? He organised the finance for Britain and France. By 1918, France and UK owed £2.96 billion to the USA (in 1918 figures). The American government would not let Britain and France off the hook for the repayment. Inter-allied debt was thus a factor in the Great Depression of the late 20s and the 30s.

After effects of the war

There are new borders, including for the UK. Many of these borders are arbitrary and imposed without any vote of consent from local populations. The ones in Eastern Europe and the Middle East are cases in point.

The Spanish flu killed more people than WWI did. It seems to have been a hybrid of two strains which came together in France in mid-1918, at least partly due to the movement of large numbers of soldiers in cramped conditions, to form a superbug. It is “Spanish” because the Spanish newspapers were not subject to censorship and could report it. In Spain, the flu is called the French flu because it came to Spain from France. Amongst the 50 million or so casualties was Mark Sykes of Sykes-Picot agreement fame, or infamy.

Power vacuums - the “Wars of the Pygmies”. Churchill used this expression at the close of WWI to describe the chaos which was erupting and would get worse, primarily the border wars.

Chaos and civil disorder – a major cause of collapse of all the Central Powers, but the chaos and strife went far beyond that. The 11th November 1918 was far from being the end of death, destruction and chaos for citizens of many countries, including the UK.

There were fewer democracies in Europe in 1939 than in 1914. If President Woodrow Wilson’s idea of democracies and self-determination had not been sabotaged by the colonial powers, the reverse would have been the case.

There was unrest in Afghanistan and India. Afghanistan was the graveyard for British imperial ambitions in the 19th century, and there was another revolt in 1920 in Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq, which we will see a bit more about shortly. In India, instead of freedom and democracy, there were the repressive Rowlett Acts. In April1919, there was the Amritsar massacre where, depending on the source, between 500 and 1,500 unarmed Sikhs were shot dead at a spring agricultural gathering by the British army, for no obvious reason. The general in charge, Reginald Dyer, was allowed to retire from the army but was given a gratuity. He was shot and wounded by a Sikh nationalist in London in 1941 and the former governor was killed. The Amritsar massacre flipped Indian political opinion from co-operation with the British Raj, seeking perhaps a status like Australia or Canada, to an independence movement.

Curzon’s hegemony – a buffer zone for India? Lord Curzon had been Viceroy of India. At this stage, he was Foreign Secretary but still obsessed by India. In the post war Middle East, he had the totally impractical idea of a so-called “buffer zone” for India which, in reality, meant occupying and controlling a number of countries surrounding India.

Populations moving (and after WWII). People moved from country to country, either as refugees or because their area was transferred from one country to another, usually without them having any say whatsoever in the matter. Studying this issue is even harder from our perspective today as there were massive population movements after WWII, and indeed the annihilation of populations.

Names change, both places and people (and after WWII). Place names change over time and/or are known by different names in different languages. People, often politicians, change their names or adopt new ones, Stalin, and Ataturk to name two. Ordinary people sometimes had to change their names to fit in with the ethnicity of their new overlords.

How many treaties?

Well, everybody knows there was only one treaty to decide everything after WWI – the Treaty of Versailles. Not quite, there were -

- Versailles – 23 June 1919: Germany

- Neuilly – 27 November 1919: Bulgaria

- St Germain – 10 September 1919: Austria

- Trianon – 4 June 1920: Hungary

- Sevres & San Remo – August 1920: Ottoman Turkey and its colonies

plus many more!

Look at the dates of these treaties – they have taken a huge amount of time to produce, when matters on the ground have not been standing still. The Sevres treaty is almost two years after the Armistice with Turkey!

The context of the Paris discussions

Many commentators get hung up on the wording of the treaties and do not understand the context. The enemy nations were not there at Paris. There were no negotiations. They are not true treaties where the parties concerned come to an agreement. They cannot be – the opposition was not there!

The following is a quotation from Harold Nicolson (Head of Foreign Office):

Had it been known from the outset that no negotiations would ever take place with the enemy, it is certain that many of the less reasonable clauses of the treaty would never have been inserted.

In other words, it was intended as a negotiating position. The following is a comment from Paul Cambon, the veteran French ambassador to the UK. It does not paint a happy picture of competence.

No matter how hard you try, you cannot imagine the shambles, the chaos, the incoherence, the ignorance here.

In this context, Woodrow Wilson promoted the idea of self-determination for populations and the League of Nations to settle disputes. The French and British were more interested in grabbing new colonies and holding on to their existing ones, so undermining the idea of self-determination at every turn.

Lloyd-George wanted to secure Middle East oil for the Royal Navy and did try to make the treaties less harsh. He did succeed in creating a plebiscite in Upper Silesia on the (new) Polish-German border, which happened in 1921, with British troops there to try to keep order.

Clemenceau was the 77 year old French premier and he made extreme draconian demands. He was highly argumentative, even challenging Lloyd George to a duel in the middle of one heated discussion!

There was no Russian involvement. This is the biggest country in Europe and a key member of the Entente, yet the Russians were not at the Paris discussions. Do not believe that this was a meeting of the “victors” as it cannot be without the Russians, and of course the Japanese were side-lined. In fact, by 1918 the British, French and other powers were interfering in Russia trying to control the internal political affairs, with total lack of success, perhaps not surprisingly.

Japan was snubbed. Ultimately, these were racist times and the Japanese were non-whites. To add insult, the 1923 Washington Naval Treaty decided that the strengths of the navies of the world should be 5:5:3:1.75:1.75 for USA, Britain, Japan, Italy and France. It was referred to as the “Rolls Royce, Rolls Royce, Ford” comparison. The snubbing of Japan and the loss of face, an important matter to all Japanese, resulted in an alienation of Japan from Western Powers and ultimately it ending on the Axis side in WWII.

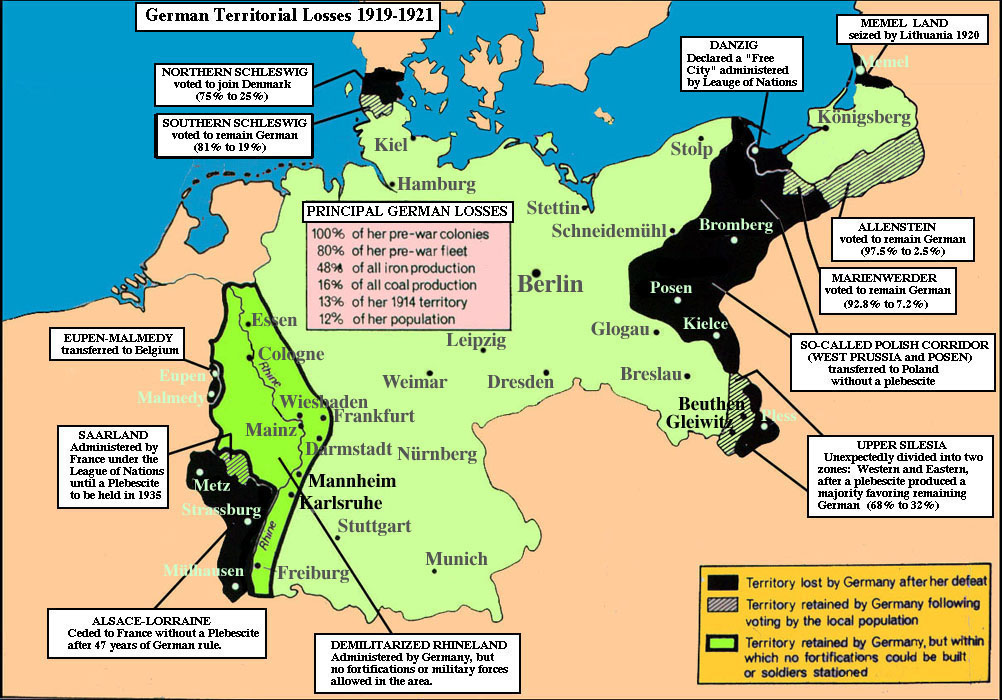

Germany lost 6.5m people and 70,000 square kilometres of land as a result of the Versailles Treaty.

So, Germany lost (see map below):

- Alsace-Lorraine to France

- Eupen and Malmedy to Belgium

- North Schleswig to Denmark

- Danzig to the League of Nations (as a “free city”)

- Polish Corridor, Posen and half Upper Silesia

- Memel to Lithuania (now Klaipeda)

- Saar to France for 15 yrs, then a plebiscite (which returned it to Germany)

- The Rhineland occupied for 15 yrs

- Its colonies removed and given to the Allies

Germany after Versailles (from Professor John Heineman of Boston College - https://www2.bc.edu/john-heineman/maps/1930smaps.html)

Bulgaria in the Treaty of Neuilly (27 November 1919) lost:

- 18,865 square kilometres

- Thrace awarded to Greece – no sea access to the Aegean Sea

- Macedonia to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, Slovenes (Yugoslavia from 1929)

- South Dobruja to Romania (and it was in fact returned to Hungary after WWII)

Effects:

- 250,000 refugees from the lost territories

- A greatly reduced army of 20,000, and a gendarmerie of 10,000

- Destabilisation – quasi civil war, bloody clashes

Bulgaria after the treaty of Neuilly sur Seine

Bulgaria after the treaty of Neuilly sur Seine

Austria in the Treaty of St Germain - 10 September 1919:

- Became Deutsche Oesterreich – the German Eastern Regime (“Austria” being an Anglicisation of the proper German name)

- The Austrian government went to Paris expecting to hear that they had become a state within Federal Germany, so were rather surprised to hear that the Allies had changed their mind (because of Clemenceau)

- The army was reduced to 30,000 (which lead to the rise of paramilitaries which the government could not control with such a small army)

- Val Canale and the Sud Tyrol were allocated to Italy

- Part of South Carinthia, and the Seeland were allocated to the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

- Lower Styria was allocated to the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

- Klagenfurt: a plebiscite took place, and also fighting between Slovene and Austrian troops: the area voted to remain Austrian

- Burgenland: fighting between Austria and Hungary – settled by the Venice Treaty 1921

- Trieste, Trentino, Dalmatia were assigned to Italy

The brown area is Austria in 1914. The red line around the word “Austria” on the left was Austria after St Germain.

Hungary in the Treaty of Trianon of June 1920 lost

- In total, Hungary two thirds of its pre-war territory and 73% of its population, including some 4 million Hungarians

- Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia to the new Czechoslovakia (without asking the Slovaks or the Ruthenians, who ended up in the Ukraine after WWII)

- Transylvania to Romania

- Burgenland to Austria (except for the town of Oedenburg)

- SW lands to Croatia and Slovenia (part of the KSCS)

- Two small northern areas to Poland

There was also an invasion of Hungary by Romania in 1919.

The red line is Hungary’s 1914 boundary and the grey area is Hungary after Trianon. (From Robert Gerwarth)

Ottoman Turkey in the Treaties of San Remo and Sevres (spring 1920)

Treaty of Sevres:

- recognised independent Armenia (destroyed by Turkey in December 1920)

- set up international control over the Bosporus (and the occupation of Constantinople)

- ceded parts of Anatolia to Italy and France (and the United States who didn’t want it)

- awarded to Greece most of Thrace and the right to govern Izmir (Smyrna); and

- took control of Turkey’s finances (the only enemy state where this happened)

Dismemberment of Turkey (From Robert Gerwarth)

Yellow zones are Greek, purple is the International zone, green is Italian, sky blue is French, orange is British, red is American and grey is Armenian. The Americans were never there and the USA was never at war with Ottoman Turkey.

The Treaty of San Remo divided the Middle East between France and Britain and re-cast Sykes-Picot in Britain's favour.

Turkey and Greece – the Asia Minor War

There were Italian territorial ambitions in Turkey, with visions of recreating a second Roman empire, hence their demands in the Sevres discussions. In January 1919, the British occupied Constantinople and General Milne of the Salonika force, as it was, moved his headquarters to Constantinople.

In May 1919, the Greeks invaded Western Anatolia. Lloyd George had encouraged the Greeks to attack Turkey.

The Allies were talking to the Sultan as the supposed head of the Turkish state but he was isolated in Constantinople and under the Allies’ thumb. Mustafa Kemal won the 1920 election and moved the parliament to Ankara in central Anatolia, away from the reach of the Allies. Central Anatolia is a plateau which is hot and arid in summer and very cold in winter. It is therefore a hostile environment for any invader.

In November 1920, Kemal defeated the Armenians whose state ceased to be an independent entity. He then defeated the French forces in SE Anatolia. There was a massacre of 10,000 Armenians at Maras.

In March 1921, the Treaty of Moscow was concluded between Turkey and Bolshevik Russia. Under this treaty, the Russians agree to supply arms and money to Kemal, as the Russians would be very happy to see the Allies pushed out of the region.

In March 1921, the French withdraw from Turkey entirely. The Greeks attacked Ankara but the Turks held out. The Greek army retreated westwards toward Smyrna and massacred Turkish civilians on the way. In September 1921, the Greek army evacuated Smyrna.

The Greek government in effect abandoned the civilian population. The administrator who left a day before Kemal’s forces got there, Aristeidis Stergiadis, said:

“Better for them to stay here and be slaughtered by Kemal, than for them to go to Athens and turn everything upside down”

Over the course of two weeks between 12,000 and 30,000 civilians were massacred at Smyrna. We know about it today because Ernest Hemmingway was there as a reporter for the Toronto Star newspaper. Obviously, he was not everywhere in Anatolia and there are countless massacres of civilians which were not recorded. In Smyrna, there were 21 Royal Navy and French naval ships in the harbour. They did rescue some refugees but otherwise did not intervene.

The Greek troops who had by now returned to Greece mutinied and there was a coup. On 27 September 1922, a new Greek government under Venizelos was formed. On 11 October 1922, a Greek- Turk armistice was signed at Mudanya.

In September 1922, Kemal’s forces were advancing on the international zone and surrounded an isolated small British garrison at Chanak at the Western end of the Bosporus. Lloyd George threatened war but Britain would have needed the support of the dominion armies. Both Canada and Australia said “no”, South Africa did not reply but little New Zealand offered to send troops. This was indicative of the new power balance between Britain and its dominions. Before 1914, the dominions needed Britain; in 1922, Britain needed the dominions in order to be able to take major military action. The prospect of re-igniting WWI was massively unpopular in Britain. The Conservatives did not remain in the coalition government which now fell, thus ending Lloyd George’s career. He was never in power again.

In 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed between Turkey, and Britain, France, Italy, Japan, Greece, Romania and KSCS. This was a “proper” treaty, unlike the Paris quasi-ultimata, which did produce peace as they were one-sided. One of the consequences of the Treaty was the so-called “exchanges of population”, in reality forced movement of populations in which many people died, but it was better than remaining behind where one’s fate was very likely to be death. The exchange of population resulted in the movement of 1.2 million Greeks and 400,000 Turks. This included the Pontic Greek population from the Black Sea coast, who had been there since 700BC. The Americans, by the way, eschewed the whole idea of occupying Turkey. Although there was a nominal American zone under the Sevres Treaty, they were never in Turkey (with whom, incidentally, they were never at war).

The British involvement in the occupation of Constantinople was, and probably still is, highly controversial to the extent that this chapter of the official British history of WWI was not written until 1944, and not published until 2010. A contemporaneous review of Keith Jeffrey’s book The British Army and the Crisis of Empire 1918-22 criticised his book, written in 1984, for not dealing more with Turkey but in fact the official history had not been published by that stage. It is worth recording that British Army were in Constantinople until as late as October 1923.

This is Karasouli CWGC cemetery in Northern Greece, with a cairn, rather than the more common cross of sacrifice, as this was a Muslim area. However, this is not a Muslim area today, and indeed the name of the town is different today – it is now Polycastro. If one ventures across the border into the Republic of Northern Macedonia, the Muslim villages are still there, as that area would have been part of Servia in 1922. (The Welsh flag is for a local lad from here in North Wales who is commemorated in Glan Conwy on a family headstone).

The next part of this article is here