What happened next?

World War II is over but WWI is not yet finished.

This is a quotation from the Guardian newspaper in March 2018. It was made by a Turkish foreign ministry spokesman to a journalist. The spokesman is, of course, talking about Syria and the surrounding region. Indeed, the places where Syrian refugees are found today are the very same places where Armenian refugees were found 100 years ago. How things change yet remain the same.

This talk is looking at the period from November 1918 to 1923. Anyone who believes that the chaos, death and destruction finished on 11th November 1918 is seriously mistaken. This is the era of the so-called war of the pygmies, to quote Churchill, and also of much internal strife in Europe and further afield.

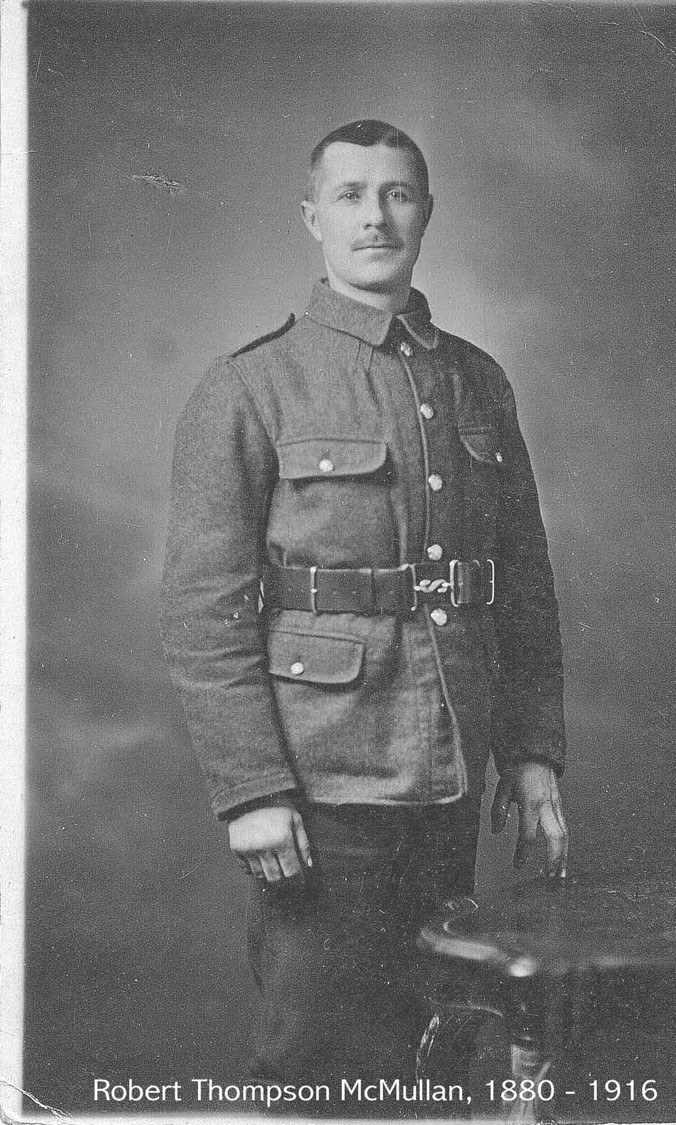

Why am I interested in WWI? Well, the photograph of the soldier is of Private Robert Thompson McMullan of the 10th Inniskilling Fusiliers. He was wounded in the attack at Thiepval on the Somme on the 1st July 1916, and died in the Casualty Clearing Station on 3rd July. He was my grandfather.

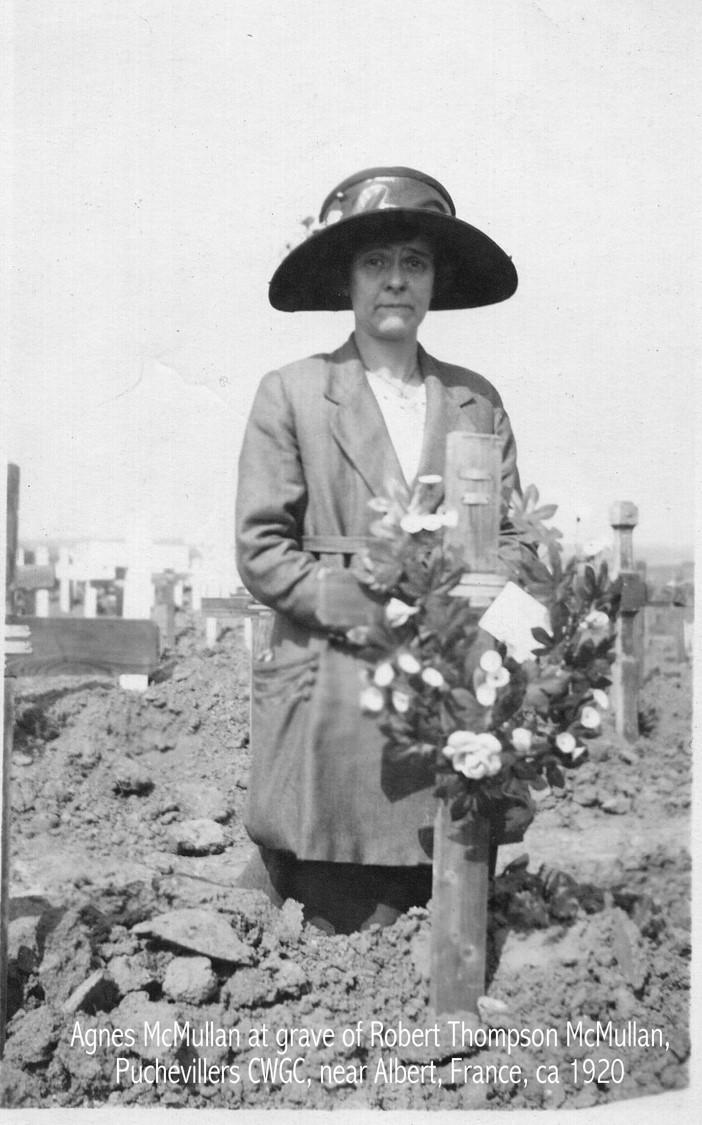

The second photograph is of my grandmother at his grave in about 1920. It is worth remembering that she was a widow for 41 years. Her visit was, we believe, part of a St Barnabas pilgrimage, which were subsidised visits for relatives of deceased serviceman. It was the only time that she was there. You can see the state of the cemetery. It is clearly less developed than it is today. However, some work has certainly been done in that the grave markers are standard wooden crosses with metal strips for the names and other details. In the course of this talk, you will see two other photographs of the same cemetery, one during the war and one taken recently.

Let’s test your knowledge of this period, post 11th November 1918.

- 3 VCs were awarded for an action 18 August 1919

- Which service?

- Where?

- Who was the enemy?

- Which country lost most land and people?

- Most important person in WWI?

- Which enemy capital was occupied for 4 years?

- What internal UK security issue were Generals Wilson and Rawlinson discussing on 28 Jan 1920

- Well, here is a rather interesting question to start with. The service in question was the Royal Navy. The place was Kronstadt, which sounds German. But in fact it's not in Germany. It is the naval base which protects Petrograd, otherwise known as Leningrad, or again as St Petersburg. Which means that the question of "who was the enemy" can be answered by saying it was the Russians. The problem is, which Russians? It was the Bolsheviks, or indeed arguably the enemy was Bolshevism. So, how do you fight a philosophy with armed force? I suppose the only answer can be, with extreme difficulty.

- Which country lost most land and people, excluding the losses of empire? The answer is Hungary, which among other population losses, lost 4 million ethnic Hungarians.

- Who was the most important person in World War 1, and he didn't wear a uniform nor was he ever elected? The answer, I would suggest, is JP Morgan, the American banker. Without him and his fundraising activities, the Entente effort would have ground to a halt in 1915. You cannot run a war without a lot of money. It can be argued that the Americans had to enter the war in the end on the Entente side to protect their investment. The other side of the coin is that the money had to be repaid and, as we will see, that had a crippling effect after the war on both Britain and France.

- The enemy capital which was occupied for 4 years was not Berlin. It was, in fact, Constantinople, or of course Istanbul - names change. This occupation may be forgotten in the west but it is still vividly remembered in Turkey. It was also the only country to have its finances taken over by the allies.

- Generals Wilson and Rawlinson were discussing the threat of Bolshevism in Liverpool. In particular, how to protect London and the Home Counties from the ravaging hordes from the North and Midlands of England, and which regiments could be relied upon to do so.

The post-1918 landscape in the UK

Let us look at the situation in the UK as it was in 1918, and broaden it out to see how these factors applied in much of the rest of the world, developed or otherwise.

- Widows, and those women who could not find a husband due to the huge number of men killed in WWI

- Children without a father: 350,000 in UK

- Unemployed service men

- Labour unrest: the “triple alliance” of trade unions – miners, railway workers and transport workers

- Disabled service men – needing medical treatment and pensions.

- Internal strife: personal stories

Jock B was my brother in law’s father. He was a regular soldier before WWII and served right through it (and you have one guess at his ethnicity). His first introduction to Belfast was in 1935, lying in the gutter and being sniped at in the city centre. My father in law, James R, who is 96 years old shortly, remembers as a young boy having to lie flat on the floor of the tram to avoid snipers when passing through certain areas of Belfast. Yes, these recollections are 1930s but they are first hand witness accounts. So, here we have civil strife in the UK, and Belfast may have been extreme but civil strife there was in various parts of the UK, more typically as industrial unrest.

- Displaced persons: personal stories

Keith Jeffery was professor of British history at Queens University, and he and I were at school together. His father was the vice principal and he spoke with a Dublin accent. They were a protestant family who had moved north after the partition of Ireland, ie they changed country. Sean McG is a Scottish accountant whom I worked with in London. His great grandfather worked in the shipyard in Belfast. On account of the attacks on Catholic workers in the shipyards in the period 1920 and after, many Catholic workers were found jobs in the shipyards around Glasgow. So, we have a Catholic family who moved across the Irish Sea because of civil strife. These stories were repeated millions of times throughout Europe and the Middle East.

- Orphans: a personal story

Peter G’s father had been a 9 year old Serbian orphan on Crete at the end of WWI, and was adopted by an English couple and brought to the UK. So, we have countless children without families who perhaps were less fortunate than Peter’s father.

Myths – rewriting history

History has been distorted both by wartime propaganda and after WWI. Here are a few instances.

- Brig Gen Gordon Strachy Shepherd

We will come to him in a moment.

- Lt Col Lawrence, Thomas Edward

Otherwise known as Lawrence of Arabia. In truth, his military Adventures in World War I were not of any major importance. Yes, the David Lean film is absolutely wonderful but don't confuse it with fact (and Lawrence wrote the book!). Faisal was making contacts in Damascus in 1915 before Lawrence was on the scene. The attack on the train at Deraa did not in fact help Allenby. Perhaps where Lawrence's legacy really lies is in what he tried to do for the Arabs after WWI, as an advisor to the British government. Certainly, he had great misgivings about the decision by Gertrude Bell to create a country with Shias, Sunils, and Kurds, into what we know today as Iraq. Was Lawrence correct in his misgivings? Yes, I have to say that the world would be a better place today if Lawrence, a man who spoke Arabic and knew the Arabs, had been listened to by the governments of the day.

- Angel of Mons

This was a creation of a journalist. To quote one veteran of the retreat – “we were dog-tired and imagined we saw various things, but no angels!”

- Voie Sacree ("The Sacred Road") but where is Petain?

This was another creation of a journalist, certainly as regards the name. The whole relief strategy for Verdun was devised by General Philippe Petain, but if you go to Verdun today he is the "Man Who Never Was" because of his role in the collaborationist government in France in World War II. He has been airbrushed out of history.

- The Lost Battalion

This was another journalistic creation. It related to the American campaign in Meuse-Argonne in September 1918. The soldiers in question were not a battalion and were not lost – pinned down, yes, but not lost.

- Anzacs

The issue here is the Anzac myth. If you believe the myth, you will be amazed to hear that there were other British army soldiers in Gallipoli, and the French outnumbered everybody! Don’t let the truth get in the way of rampant nationalism!

- Vimy Ridge

A similar situation for the Canadians, dare I say it – Currie was indeed a good general but it was the Canadian second division that took Vimy and their leader was the very English Julian Byng. The miners who dug the tunnels were from the North of England, and the British 5th Divn were there as well. You just need to keep it all in perspective!

- The Lusitania

Not as innocent as often portrayed – she was carrying small arms ammunition, probably artillery shells, and the wreck was apparently depth-charged by the RN, possibly to hide the evidence? Surely not!

A case in point – Gordon Strachy Shepherd

This is the headstone, on the right, of Brigadier General Gordon Strachy Shephard. It is in a CWGC cemetery at La Pugnoy, west of Bethune. He was killed in January 1918 in a flying accident. His entry in the cemetery register refers to his decorations and his upper class family with a posh London address. However, look at the next photograph (below) and you will see that it features two men on board the Askard, running German guns into Dublin in 1914. The man on the left is Gordon Strachy Shephard, as a serving British Army captain. Isn't it odd that his CWGC entry mentions his medals both British and French but makes no mention of this episode in his life? Incidentally, the man on the right is Erskine Childers who during WWI worked for Royal Navy intelligence, before reverting to his Irish nationalist activities, but of course he was as upper class English, as was Shephard. I think Shephard is also a very awkward case for Irish nationalists to deal with, as how can they commemorate a British Army officer who was on their side? He is a fascinating and enigmatic character.

This is the headstone, on the right, of Brigadier General Gordon Strachy Shephard. It is in a CWGC cemetery at La Pugnoy, west of Bethune. He was killed in January 1918 in a flying accident. His entry in the cemetery register refers to his decorations and his upper class family with a posh London address. However, look at the next photograph (below) and you will see that it features two men on board the Askard, running German guns into Dublin in 1914. The man on the left is Gordon Strachy Shephard, as a serving British Army captain. Isn't it odd that his CWGC entry mentions his medals both British and French but makes no mention of this episode in his life? Incidentally, the man on the right is Erskine Childers who during WWI worked for Royal Navy intelligence, before reverting to his Irish nationalist activities, but of course he was as upper class English, as was Shephard. I think Shephard is also a very awkward case for Irish nationalists to deal with, as how can they commemorate a British Army officer who was on their side? He is a fascinating and enigmatic character.

Soldiers’ issues

What were the key issues affecting soldiers?

- Going home?

Well, you might think that as the war ended on 11th November 1918, you could go home on 12th November. Unfortunately, this was not the case. The soldiers were not demobbed on a "first in, first out" basis, but on the grounds of their supposed utility in civilian life. This produced a lot of resentment amongst the soldiers who saw it as a very unfair system. For those who were discharged, there was the prospect of unemployment as there was a major depression following the war.

- Folkestone mutiny 1919

So, there was the mutiny at Folkestone in 1919 of some 10,000 troops who refused to go back to France. The army units who were assigned to sort out the situation in fact were themselves in great sympathy with the mutineers, so the army high command had to negotiate with the mutineers.

- Bodelwyddan churchyard – Canadian mutiny 1919

In North Wales, there are graves in the grounds of the marble church at Bodelwyddan, some of which are from a mutiny in the Canadian army at nearby Kinmel Bay camp in March 1919. The issue was of the troops being kept in cramped, cold conditions and there being a very slow rate of repatriation to Canada, in contrast to the situation with the American troops. Most of the CWGC graves in the cemetery are from the Spanish flu outbreak at the end of, and just after, the war.

- Thornhill, Ontario graves

In an old Ontario cemetery, a researcher has recently discovered some forgotten graves. It turned out these were of ex-soldiers who are living rough on the streets in Canada. They had been arrested and convicted of vagrancy, as a ploy to find them accommodation on a nearby prison farm at least they had shelter and food. Over time, some of them passed away, hence the graves

- Clearing the dead – Ernest Corkill

Finding the dead is an issue will come to end just a moment, with the example of the case of Ernest Corkill.

- Salvage and clearing the battlefields of ordinance

Salvage was an important issue. Not only have the battlefields to be cleared of equipment and wreckage, but it was also a source of income to the locals in Northern France and Belgium at a time when farming operations were greatly curtailed because of the ordinance lying around and broken infrastructure, including basics like field drains. Clearing the battlefields of ordinance was an issue that often fell to the Chinese and Burmese labour Corps. They were not used in searching for soldiers, largely on racist grounds. When you see Chinese and Burmese Labour Corps graves today, the dates of death are often in the 1919 to 1920 period because of this work.

- Memorials – CWGC and others: strife with allies

Memorials are important but were also a source of strife and disagreement, including with allies. We will deal more with this issue below.

- Families and commemoration: visitor numbers

Pilgrimages and tourism to the battlefields started immediately after the end of the war. A question at the time was - what would happen when the generation that knew the soldiers personally passed away? Would anybody come to visit the cemeteries, the memorials and the battlefields? We know today the people, of course do you still go, I might add rather to the amazement of the French. Visitor numbers have been increasing since about 1990, and obviously of the centenary has produced a marked increase.

- Pensions to widows and orphans

Pensions repaid to the widow's and families. This could take some time to work its way through the bureaucracy. However, although the pensions were meagre, they were a steady income in the hard times of the 1920s and 30s.

- Votes for women and for the soldiers!

Much has being made of the introduction of votes for women in the Representation of The People Act 1918. However, what tends to be forgotten is this Act also made it possible for the soldiers, sailors and airmen who had been fighting the war to have a vote. The situation before this Act was that you had to be resident in your constituency for 12 months in order to be able to vote in the election. Obviously, almost all service men would have been excluded from voting if this situation had continued. (There was also an obsolescent property qualification under the old legislation).

Coming home?

The photo on the right is of Mill Road CWGC cemetery on the Somme. The grave of L/Cpl David Lamont is one of those graves. His parents believed to their dying day that he was alive and wandering in France, suffering from amnesia, in spite of him being in a marked grave. How many other families deluded themselves like this?

Clearing the dead

Detachments of soldiers were assigned to clearing and recording the dead (and here we are primarily talking about France and Belgium but this work was also done in Gallipoli). This included so-called concentration, which means removing casualties from field graves or small cemeteries and putting them into bigger CWGC cemeteries.

By August 1921, some 204,654 remains had been concentrated on the Western Front. This is an incredible number. However, as we will see later, finances were getting tight, and the army was being reduced greatly in size. In November 1921, the then Secretary of State for War maintained that the government could cease this work as only “invisible” graves remain (in a letter in “The Times”). In fact, up to 300,000 were unaccounted for in France and Belgium. The IWGC (today the CWGC) took over with greatly reduced resources and finance.

In 1921-28, 28,036 were found. In 1928-37, a further 10,000 were found. By way of example of the means by which remains were uncovered, in the period 1932-36 52% were found by metal searchers, 30% by locals often in farming or building operations, and 18% by the French government.

The photograph above is of an exhumation party. One soldier holds a steel helmet that presumably indicated to them the likely presence of a body. The two soldiers with spades are attempting to uncover the remains. This was unbelievably unpleasant and arduous work. (The photo is from Photographing the Fallen on the work of Ivan Bawtree who was a Graves Registration Unit photographer, written by his great nephew Jeremy Gordon-Smith.)

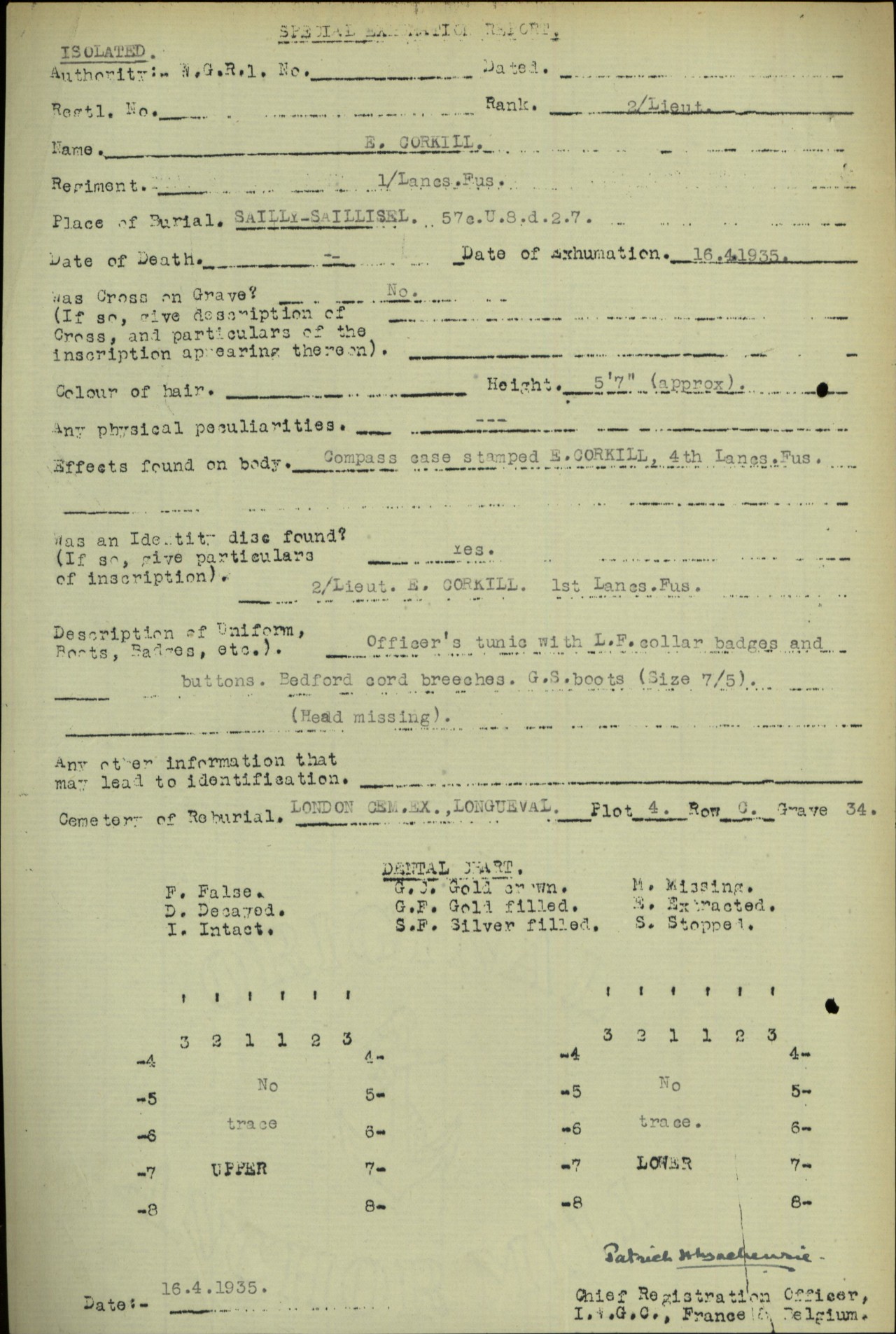

A recovered soldier - Ernest Corkill

He was born at Heswall, near Chester and educated at Calday Grange grammar school. He worked as a bank clerk, joined up in November 1914 and was killed on 28th February 1917. We have his exhumation record (below). He was discovered in April 1935, buried in a field grave near the village of Sailly-Saillisel. He was identified from the metal identity disc (which he will have purchased himself as the army ones decayed rapidly) and from his name on his metal compass, found with the remains. There were also Lancashire Fusiliers metal collar badges and remnants of uniform consistent with an officer. There were no dental records as the head was missing. He is buried in London Road cemetery extension at Longueval, near High Wood. He is a rare case of identification being possible.

He was born at Heswall, near Chester and educated at Calday Grange grammar school. He worked as a bank clerk, joined up in November 1914 and was killed on 28th February 1917. We have his exhumation record (below). He was discovered in April 1935, buried in a field grave near the village of Sailly-Saillisel. He was identified from the metal identity disc (which he will have purchased himself as the army ones decayed rapidly) and from his name on his metal compass, found with the remains. There were also Lancashire Fusiliers metal collar badges and remnants of uniform consistent with an officer. There were no dental records as the head was missing. He is buried in London Road cemetery extension at Longueval, near High Wood. He is a rare case of identification being possible.

The next part of the article is here