Book Review

The British Army in Mesopotamia 1914-1918

Paul Knight

McFarland 2013

If you want to read about the Mesopotamia campaign, then this is the source material. It is, as far as I know, the only book on the topic. Certainly, it is the only one where the author has been to many of the sites, as he is an officer in the Army Reserve and served in Iraq. There is a marvellous photograph of him at Ur of the Chaldees, the birthplace of Abraham.

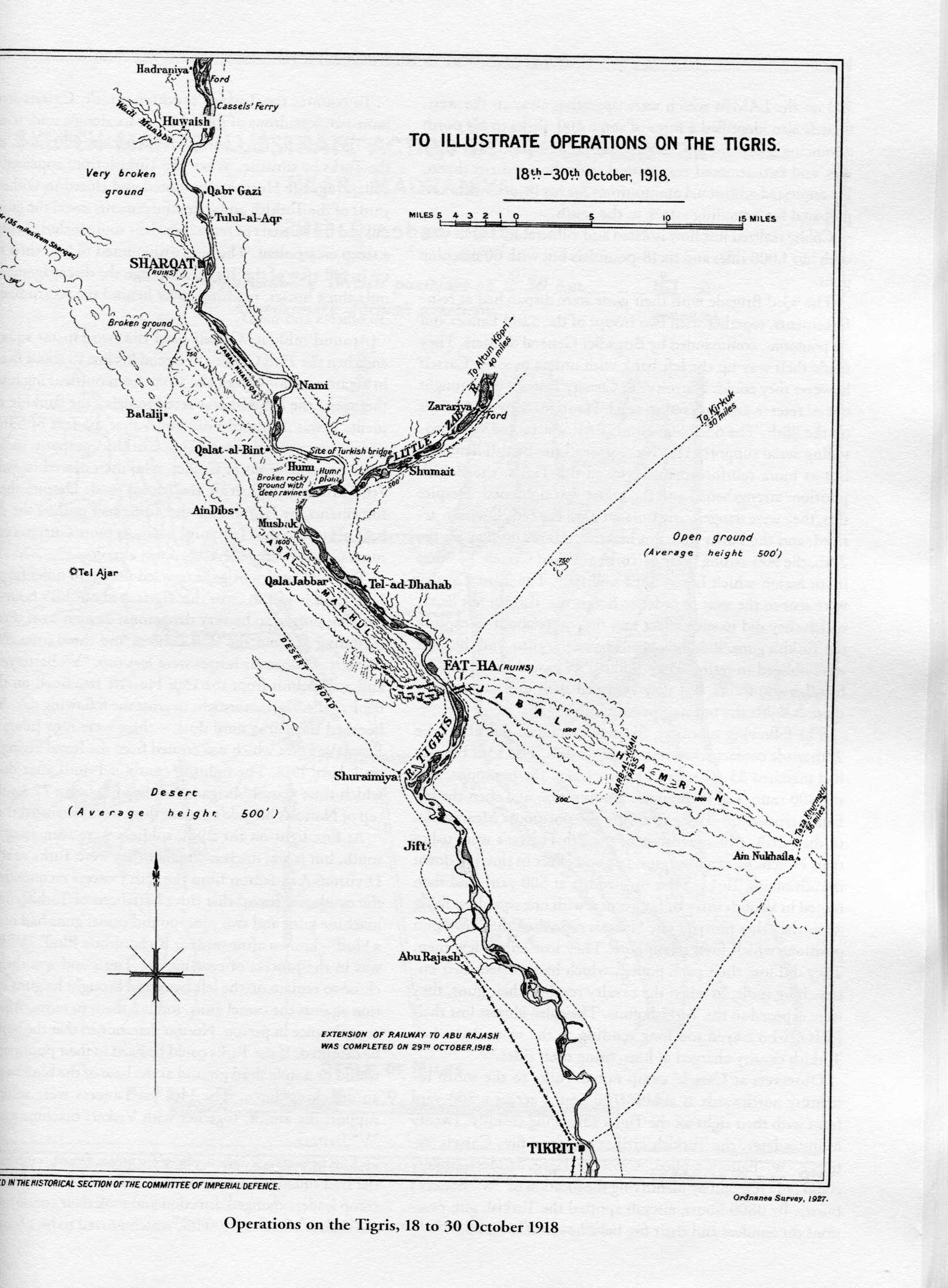

Not surprisingly given his background, the book is written from a soldier’s perspective. There is a lot of detail on the numerous actions undertaken by the mixed British army and Indian army forces, with many sketch maps to explain the actions taken. These are very helpful and make sense of actions that would otherwise be impossible to understand. If you want to know the detail of these actions, as the British Army in 21st century Iraq did, then this is excellent.

The initial aim of the campaign was to secure oil supplies, but at the time this was Persian oil. The key company was the Anglo-Persian Oil Company which became British Petroleum in 1934. There was no Arab oil until well after WWI. It simply had not been discovered yet. The key target for the British was Basra, with the Shat al Arab waterway and the oil installation at Abadan, in order to secure the supplies of Persian oil for the Royal Navy. Although the book is entitled the British Army in Mesopotamia, a key feature of the campaign was the Royal Navy and the support it gave through its armed river boats. Much later in the campaign, armoured cars, initially operated by the RNAS in WWI, would enable the British/Indian forces to operate further away from the waterways, not least as they are more resilient to desert conditions than are horses. Horses need to be fed and watered whether they are being used or not.

One of the many excellent sketch maps in the book

One of the many excellent sketch maps in the book

Once Basra was secured, arguably the British should have consolidated their position and stayed there. But they did not. First, they advanced to Qurna, the legendary site of the Garden of Eden. This strategy of advancing up country eventually lead to over extending lines of supply and communication culminating in a pointless attempt to take Baghdad, a place with no value, military or otherwise, save for propaganda. This was in 1915 and Gallipoli was now known to be a disaster, with matters not a lot better on the Western Front. So, there was a desire for a "success".

The British/Indian forces fell back to Kut thus starting the longest siege in modern British military history. It was a surrender only exceeded in size by the surrender of Singapore in 1942. General Townshend is remembered for enjoying a cosy captivity in Constantinople hobnobbing with the upper echelons of society, whilst his men died in their thousands from ill treatment, starvation and disease. If Kut is half-forgotten today, then the losses of the would-be relief forces are totally ignored. The book puts all this into perspective.

In 1917, Baghdad was indeed taken and, from the memoires of those involved, it was pretty pointless, as it was far from being the fabled city of the Arabian nights, or of learning and libraries. Ultimately, the British/Indian forces pushed up to Mosul and to the Persian border. This rendered the secret Sykes-Picot agreement pointless, if indeed it ever had a point, and so soured British-French relations in the Middle East for decades. Indeed, before the colonial dividing up of the area, there was no “Middle East” as such. The British created Iraq from three Ottoman “vilayets” which had not been previously linked, and created a country with Shia, Sunil and Kurds, a result that TE Lawrence had grave doubts about. Was he right?

The various VCs which were won are detailed in the book, including John Sinton who is the only person to be awarded a VC and also Fellow of the Royal Society, for his work on malaria in India after the war.

Problems of the campaign included mirages, as the terrain is totally flat, which made the work of the artillery very difficult until aerial spotting became the norm, and the local Arabs, who hated any invaders being in their country. The rivers Tigris and Euphrates were the key features of the terrain, and the main transport arteries until motor transport became plentiful, if not reliable, toward the end of the campaign. Indeed, one of the features of the Mespot campaign was the use of cavalry primarily as mounted infantry, eventually being replaced by motorised infantry supported by armoured cars. As such, the tactics were rather more modern than in Palestine, for example.

There is a chapter on Dunsterforce about which the author is more positive than perhaps the episode deserves. It was a half-baked, minute, colonial invasion force that owed more to Kipling than to military sense. It may have “stabilised” northern Persia, but its interference at Baku in Azerbaijan ended with the massacre of between 9,000 and 30,000 Armenian civilians by the Ottoman Caucuses-Islam army, as the book describes. There are maybe parallels with the modern Srebrenica massacre of thousands of Muslim civilians in the Yugoslav wars, when supposedly “protected” by a small detachment of UN troops against a major force of Serbian paramilitaries.

The presentation of various enquiries on the failures in Mesopotamia is clearly dealt with and helps to explain the screw-ups, even if those responsible largely got off the hook, as again described by the author.

As with all books, there are glitches. Kaiser Wilhelm II was the grandson of Wilhelm I, not his son. The year 1888 is known as the year of the three Kaisers for that reason, as Frederick III was dying of cancer when he became Kaiser and lasted only 99 days.

The river transport company Lynch Brothers were from county Mayo and therefore Irish.

The main glitch with the book is that the narrative gets submerged under the minutiae of the many military engagements. The two chapters at the end of the book “Aftermath” and “Conclusion” would be best being read first. The narrative would be easier to follow if each chapter had the military minutiae in an appendix as a “part 2” of each chapter, or as a “part 2” section of the book. The wealth of information is highly commendable – it just could be better organised for the reader.

Well, if you are interested in this aspect of WWI, then this is undoubtedly the book for you. It is large format, which is good for reading the many sketch maps, and is not over long at just 200 pages.

Paul Knight is a Army Reserve officer (in 1914 he would have been a "Territorial Force" officer) and who has served in what is today Iraq but was Mesopotamia in 1914-1918. His book on this campaign is available on Amazon and also from Paul at