- Details

- Category: Book review

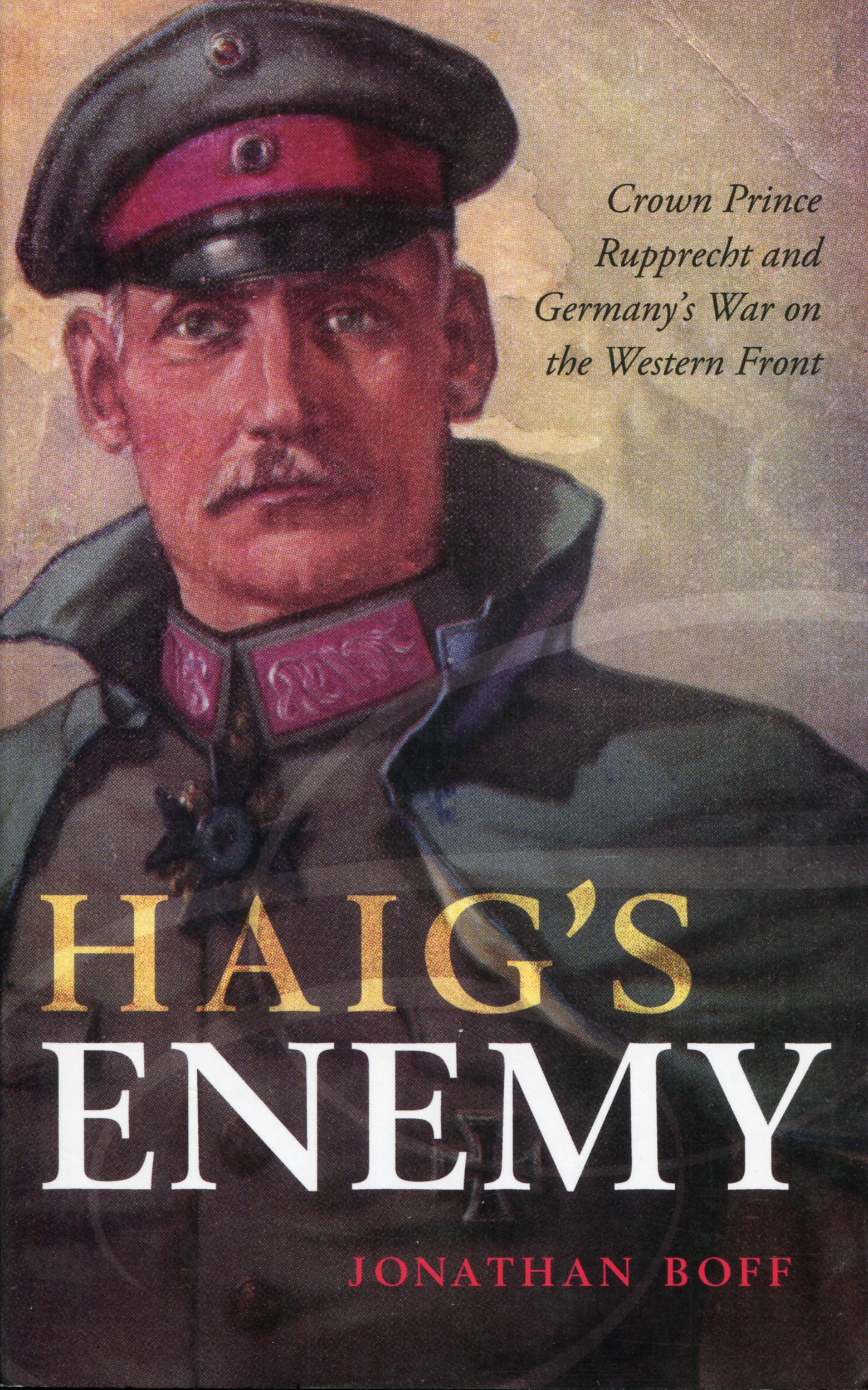

Haig’s Enemy:

Crown Prince Rupprecht and Germany’s War on the Western Front

Jonathon Boff

Oxford University Press, 2020

£14.99

The first thing that I should say is that I do like the book. The author has a very readable style and, thankfully, uses short chapters so that the author’s theme at that point does not get lost in a sea of pages, as is too often the case with history books. There are in fact 26 chapters, with clear titles, as you would expect.

I read the paperback version which has a set of maps at the front of the book that illustrate the military situation at various times and places. According to the reviews on Amazon, the Kindle version does not have the maps, which would make the battle histories difficult to understand, unless of course you are a WFA nerd who knows the ins and outs of the locations anyway!

The title is wonderful marketing, but not entirely accurate. Surely Falkenhayn and then Ludendorff were Haig’s counterparts and therefore his “enemy”? Rupprecht was an army commander, not the overall chief on the Western Front.

Rupprecht was the Crown Prince of Bavaria, as his father, Ludwig, was King of Bavaria. Germany at this stage had a number of provincial royal families, Kaiser Wilhelm II being the King of Prussia as well as being the Kaiser of all Germany. In the case of Rupprecht, these differences led to political and cultural problems. The Prussians are Protestant and the Bavarians are Catholic. The Prussians therefore tended to look down on the Bavarians and regarded them as ignorant peasants. So, when Ludendorff in 1916 considered making Rupprecht the overall commander on the Western Front, it did not happen because that would have put a Bavarian in charge of all the Prussian troops on that front, especially the Prussian Crown Prince. For the record, Falkenhayn, Hindenburg and Ludendorff were all Prussians.

The fact that Ludendorff even considered Rupprecht for such a command position indicates the basic fact about Rupprecht – he was a competent general. Unlike the Prussian Crown Prince, he did not have a “ghost” general installed nominally under his command, where in reality the “ghost” was the real commander. Rupprecht was his own man. This became clearer in the latter phases of the war when Ludendorff became even more obsessed with being in control of minutiae, and his mental instability led to him having an unrealistic view of Germany’s position. Rupprecht was not a clairvoyant but undoubtedly had a much more balanced view of the situation.

The book does have a lot of detail on the major battles on the Western Front which may seem superfluous to the WFA reader with his or her extensive knowledge but, like the sketch maps in the book, are needed for the more general reader. As is often the case with history books, the analysis is at the end of the book when it would be better having it at the front, but of course the reader can do that for themselves by first reading the chapters on Rupprecht’s character and views.

On Rupprecht’s character and abilities, to quote the author:

He proved far from a figurehead, much less a dilettante. He set a high personal standard for his officers to follow: his army and, later, his Army Group seem to have been well run and to have operated smoothly, at least until the army as a whole began to break down. His military judgment was generally good: he made sensible decisions; his troops were well prepared to fight; he oversaw an efficient logistics system which kept them equipped during combat; and he managed and directed the deployment of his reserves with care and skill. His ability was rewarded with extended responsibilities in 1916……………………

Nonetheless, it would be silly to claim that Rupprecht was one of the great captains of history. The First World War did not produce many of those. It did shatter the reputations and careers of many, though, and Rupprecht was good enough to avoid such a fate.

On the BEF and the French army:

…Rupprecht forces us to revise long cherished views about the armies of the Entente too. Most obviously, his diary reminds us how important the French were. Not only were they the main enemy from August 1914 to the end of 1916 but even thereafter he still viewed the French army as a more dangerous opponent than the BEF. Rupprecht tended to look down upon the British, considering them brave enough most of the time but clumsily handled. Even into 1918, the BEF sometimes remained poor at coordinating attacks and exploiting any temporary success it managed to achieve. The main factor behind the British success, Rupprecht thought, was weight of numbers, in men and especially in artillery. There is little evidence that Rupprecht was aware of, much less worried by, any British tactical improvement. He was less likely to note threatening British tactical innovations than instances of them repeating the same mistakes.

After WWI, there was considerable political upheaval in Germany, and certainly in Bavaria. Rupprecht fled to the Netherlands in November 1918 as Mr Landsberg. The Bavarian government guaranteed his safety, but it was not until the autumn of 1919 that he returned to Bavaria. The royal family had been deposed. His father died in October 1921, so he was then the pretender to the throne of Bavaria. More importantly, the family were able to reach a settlement with the government involving payment to them of a lump sum, and rights to certain castles and other buildings. The state took the rest.

He married his fiancée in 1921, who was 20 years younger than he, and they eventually had five children. He had a son from his first marriage but another son had died of polio during the war. Between the wars, he was a popular public figure in Bavaria. The rise of the Nazis caused him to retreat into internal exile in the late 1930s, and then flee to Italy. He narrowly missed being arrested by the gestapo in 1944, after the attempt on Hitler’s life when the Nazis hit out at anyone who was not a supporter. The rest of the Wittelsbach family were rounded up and sent to the concentration camp at Dachau, but did survive.

He died at the age of 86 in 1955 at Schloss Leutstetten. He was buried “with ceremony and pomp fit for a king” in the Theatinerkirche St Kajetan in Munich, alongside his first wife Marie-Gabriele and their son, Luitpold.

Well, as I said at the beginning of this review, I do like the book. You cannot help but admire Rupprecht for all that he was constrained by his position in the Royal Family and the politics of the era.

- Details

- Category: Book review

Book Review

The First World War Diary of Noël Drury

6th Royal Dublin Fusiliers

Gallipoli, Salonika, Palestine and the Western Front

Edited by Richard S Grayson

Army Records Society

Boydell Press, 2022

The Army Records Society produces an annual volume of the papers of, usually, a soldier who is well-known and which is edited by one of their esteemed academic historians, though sometimes the topic is a bit more wide-ranging than one person’s papers. This particular volume has been eagerly awaited for rather longer than intended, due to the Covid pandemic and the consequent suspension of publishing operations. The editor of the present volume is the professor of 20th century history at Goldsmiths College, University of London.

The story of Irish soldiers in WWI is one that has been hidden until comparatively recently, especially the history of the Southern Irish soldiers. In fact, 200,000 soldiers from the island of Ireland volunteered for service with Irish regiments. The late Professor Keith Jeffrey estimated that a further 50,000 served with other British army regiments and with the Canadians, Australians, Americans, New Zealanders and other Entente armies. At the time of Noël Drury’s death in 1975, the issue of there having been soldiers from what is now the Irish Republic serving in WWI was ignored by Irish officialdom, and unknown by the general public. The memory was kept alive by the families of those who served, and those in the Irish Defence Force with an interest in their own history.

The approach of the centenary of WWI, and Northern Ireland Peace Process, saw a new interest in WWI, not least as an example of Irishmen, and women, from all over the island working together. Our WFA colleagues in the Republic have worked hard to raise awareness of this aspect of Irish and British history. All this has led to a plethora of books on Ireland’s role in WWI, including ones on key figures with Irish connections, and those who are less well known. (Kitchener and Gough are two of the well-known ones). So, the “forgotten” diaries of a Dubliner who served in a regiment that has not existed for 100 years have now seen the light of day, some 45 years after they were deposited in the National Army Museum.

A word on the three Irish divisions in WWI is perhaps called for. The Division number of the Irish Divisions indicates their political background, in that the 10th was neutral and was formed first, as it was least trouble. The 16th was Redmond’s Irish nationalist volunteers, and the 36th was the Ulster Division, the core of which was Carson’s protestant militia, though not forgetting that there was a substantial contribution from the members of the Catholic community in the North.

I discussed with the historian Stephen Sandford, who wrote a history of the 10th (Irish) Division, that the division was rather kicked around the globe by the powers that existed at the time. Stephen said that indeed they were treated as being disposable, but for the average soldier the odds of him surviving the war were in fact better in the 10th than the 16th or 36th.

Noël Drury (1884-1975) was from a middle-class Dublin Protestant family and served most of the First World War as an officer in the 6th Royal Dublin Fusiliers (“RDF”) in the 10th (Irish) Division. The 10th Irish division was the first of Ireland’s wartime volunteer formations to be posted overseas, arriving at Gallipoli in August 1915 in the Suvla Bay landings. Drury and his battalion experienced several key phases of the Gallipoli campaign before being redeployed to Salonika in October 1915 (in fact into the mountains, while still being issued only with tropical kit). Drury was away from the battalion for a year in 1916-1917 suffering from malaria, but re-joined in Palestine towards the end of 1917. From there, his battalion was sent to the Western Front in the summer of 1918 to take part in the Hundred Days Offensive. Drury’s diaries describe training, daily life, contrasting theatres of war, and show what it meant to be an Irish officer in the British army. He was also a keen motorcyclist in his youth and took part in the Isle of Man TT races before WWI, and car races after the war. His younger brother Kenneth was a doctor who served in the army from August 1914 throughout the whole war, winning an MC in 1916 and finishing as a major. Noël Drury’s diaries were donated by his family to the National Army Museum in 1976, after his death.

For all his genuine Irish credentials, Drury had been educated at the public school of Mill Hill in North London, which was founded to take non-conformist pupils. Thus, it was unlike most public schools which only took either Anglican or Catholic pupils, as the case may be. The Drurys were Presbyterians. So, his writing is that of an English public school boy – who else would use the word “scrimshanking”? It means a shirker, by the way. He is therefore in the same category as Max Staniforth, who was with the 16th Irish Division and whose letters were also edited by Professor Grayson, ie they were both from an Anglo-Irish background. This is to the detriment of neither of them, as both authors write lucidly.

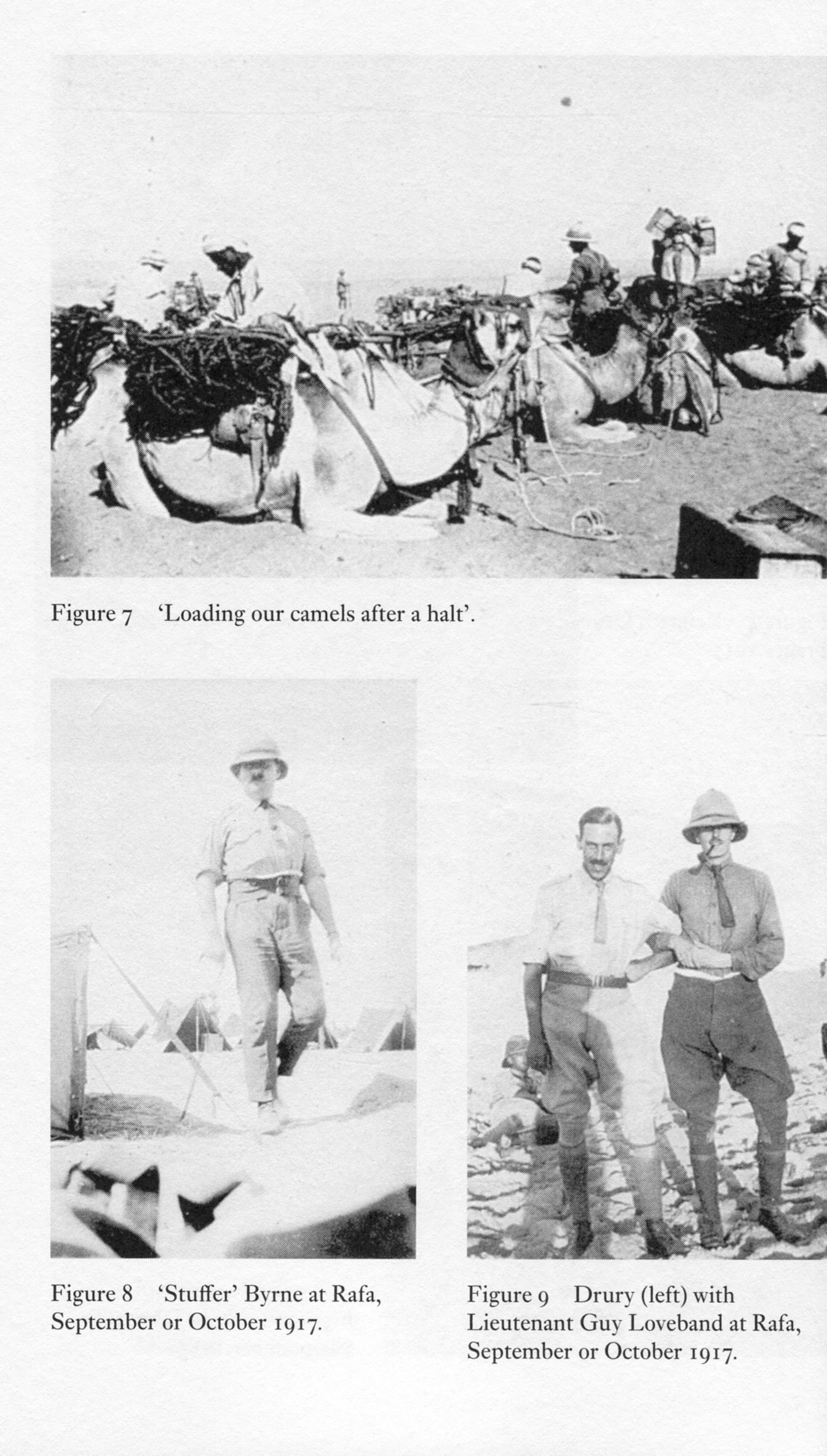

The book contains some photos of where Drury was during the war, of his fellow officers and of the man himself. It also has some wonderful words of the era and army slang, eg the Connaught Rangers were referred to as the “common dangers”.

The 10th Irish, or at least it component parts, ended up in four different theatres in WWI. After initial training, they were sent to Gallipoli via Gibraltar, Malta, Egypt and the Greek islands. The public school boy, trained in the classics, was fascinated to see some of the locations. Drury and his fellow officers tried to buy melons using Attic Greek which greatly amused the locals (as would someone in the UK trying to buy groceries using Anglo-Saxon). The voyages were not terribly pleasant in the warmer climates, especially at night when the portholes had to be kept shut for fear of the lights giving the ship’s position away to U-boats.

The arrival at Suvla Bay was to be a foretaste of the chaos of the Gallipoli campaign. The troops landed without orders and without maps. Drury is critical of the general staff for their lack of organisation. Indeed, anyone who thinks that the Gallipoli campaign could have been saved should read the first-hand accounts of people like Noël Drury.

His first experience of major action was an advance from Hill 50 towards Ali Bey Chesme. He writes “The firing was worse than I imagined it would be and I felt very scared”, with snipers hidden in trees being a particular problem. The attack failed and Drury attributed that to

“the failure by the staff to work out any proper scheme at the beginning while there was a chance of our getting there without much opposition” and “the extraordinarily bad behaviour of the 11th (Northern) Divn troops and some of the 53rd”.

The 6th Royal Dublin Fusiliers lost 11 officers and 259 other ranks, with 6 of the officers being killed, which required some reorganisation of the battalion. A subsequent attack on “KTS” ridge and a counter attack by the Turks saw more casualties. Drury was appointed adjutant which would give him greater insight into liaison between his unit and both 33rd Brigade and the 10th (Irish) Divn.

My personal interest is in the next phase of the diaries which deal with the move to Salonika on 10th October 1915. We were there a few years ago with Alan Wakefield and the Salonika Campaign Society. In Salonika, the 10th (Irish) were there to support the French in an attempt to protect Serbia from Bulgarian aggression. Drury was delighted to see Mount Olympus which had such significance to the ancient Greeks. The 6th RDF were sent north from Salonika (Thessaloniki) in November to Kosturino, a ridge high in the mountains. This is one heck of a climb to get up there today in good weather, never mind in December 1915 while carrying a lot of kit.

“It is impossible to get warm, everything is frozen solid. There were 42 degrees of frost last night – ten degrees below zero [= -23C]. We had an enormous sick parade this morning, nearly 150 men reporting. There were many bad cases of frostbite in hands and feet and ears.”

The 6th RDF were in reserve when the Bulgarians overran elements of the 10th (Irish) Divn holding the ridge on 6th December. They were covering the retreat of the French on 8th December, and saw heavy fighting. There is a certain lack of amusement on the part of Drury at the tardy French withdrawal, taking goods and animals removed from the civilian Serb population. The whole force was withdrawn to Doiran, just inside the then Serbian frontier, and then back to Salonika where they helped to construct the defensive “birdcage” line. Drury refers to his delight in seeing storks and wild tortoises, with which I heartily concur – they are definitely still there today. He also records the shooting down of a Zeppelin.

The 6th RDF had been reinforced by elements of the Norfolk regiment who apparently had a rather snotty attitude about being attached to an Irish regiment which, Drury points out, was old and prestigious having been first raised in 1641.

By May 1916, the allied forces were being extended north to Lake Doiran and the Struma valley. The heat at this time of year was oppressive. This area was subject to malaria (which has been eradicated since) and Drury did indeed contract that disease. He was eventually evacuated back to the UK for treatment for malaria and corneal ulcers. He was not back with the 6th RDF for a year.

He records the effects of the fire which destroyed much of old Salonika on 21 August 1917. The British soldiers and sailors helped the locals to evacuate whereas, according to Drury, the French and Italians got drunk on stolen wine.

In September 1917, the 10th (Irish) Divn were sent to Egypt and then to Palestine. He has a wonderful mention from his classical studies of Herodotus visiting the pyramids and describing them as being “very old” (sometime around 450BC).

The Palestine campaign was to protect the Suez Canal from the Ottoman forces which controlled the Middle East, as the canal was the gateway to the British colonies in the Far East. The 6th RDF saw little action in the first four months. They were in reserve for the Battle of Beersheba in October 1917, and were then holding positions round Gaza in early November. They did not take part in the attack on Jerusalem but had to protect the position from a possible counter attack, and spent “a miserable Christmas Day with chattering teeth and aching bodies”. Jerusalem is in the Judean Hills. He tells of later engaging a local guide to take him and his friend round the holy sites of Jerusalem.

His description of the fighting in Palestine is very much of an open country campaign, with the added problems of running ahead of your supplies, and co-ordination with other units, or even finding the other units.

In July 1918, the units of the 10th (Irish) were transferred to France. The division was “Indianised”, and stayed in Palestine but without the “Irish” designation.

In France, the 6th RDF was part of 198th Brigade in the 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Divn. Drury was in hospital for much of August with a recurrence of eye problems. He re-joined the 6th RDF on 16th September 1918 some 40 miles west of Arras. The fighting was very much a war of movement and often the heavy artillery, at least, could not keep up. So, the 6th RDF were regularly on the move, sleeping where they could in the ruins of buildings. On 7th and 8th October, the battalion was involved in fighting round Le Catelet, about 15 miles south of Cambrai. Drury noted “The enemy are now driven into open country and those of us who have been accustomed to open fighting feel much more at home than in the trenches.”

They were also involved in the attack on Le Cateau on the 17th and 18th October, along with the 2nd RDF who had fought there in August 1914. The war had now become one of pursuit, so there were no major engagements. When news of the armistice came, Drury could scarcely believe it, and as for the men “they just stared at me and showed no enthusiasm at all……..They all had the look of hounds whipped off just as they were about to kill”.

The final location of the 6th RDF was the Belgian town of Jemelle. Bizarrely, he discovered in Hastiere that the Germans had sold the locals a supply of Union Jacks with which to welcome the British! Drury secured home leave in January 1919. However, he found his brother Jack and sister in law ill with the Spanish flu. (Jack seems to have run the family business whilst his brothers were at war). When Drury was in London returning to Belgium, he received word of a deterioration in their condition. He was granted leave to return to Dublin but arrived after Jack had died. He returned to London and explained the situation to the War Office which gave him further leave. He was demobilised on 11th March 1919, without re-joining his battalion. The final entry is his diary reads “Doffed uniform and turned civilian again”.

The family paper making business seems to have run into financial difficulties in 1926 and closed. What he did for employment after that is not known. He died on 5th December 1975 at his home, in Foxrock, perhaps the poshest part of Dublin. He never married and shared his house in later years with a cousin, Winifred Drury, who seems to have been the person who donated Noël Drury’s diaries to the National Army Museum (or indeed we should say Captain Drury as he was known). Thanks to her and the Army Records Society, we have this first- hand account of the four theatres in WWI in which an Irish battalion was involved.

- Details

- Category: Book review

An Improbable War:

The outbreak of World War I and European Political culture before 1914

Edited by Holger Afflerbach and David Stevenson

Berghahn Books 2007

This is a collection of essays by eminent historians and stems from a symposium held at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia in 2004. The basic premise of the articles is that WWI should not have happened – so what went wrong? Holger Afflerbach is Professor of Modern European History at Leeds University, and David Stevenson is the Professor of International History at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

It is worth noting at the start that the consensus seems to be that the best account of the political crisis in July and August 1914 that lead to outbreak of WWI is the book, in three volumes, by Luigi Albertini, a conclusion which I would agree with. The current work is not concerned with the July crisis, as such. Rather, it looks at the historical, political and cultural factors at play in the relevant countries which lead to the crisis and to WWI.

The book starts with an introduction from former US President Jimmy Carter. You may wonder what his connection with WWI is. In fact, his father served in Meuse-Argonne in WWI. Jimmy Carter was in the US Navy and was the first member of his family even to finish high school. He served in WWII and Korea.

His introduction refers to the excessively–binding treaty system of the day being a factor in the genesis of WWI. He refers to the fact that there were no wars in Europe for forty-three years before WWI. In the US, WWI is much less in the consciousness today than are more recent conflicts, yet the US lost more soldiers in WWI than in Korea and Vietnam combined. Four empires disappeared as a result of WWI, and it was in some ways the beginning of the end for others.

Apparently, President Kennedy told his advisers to read “The Guns of August” by Barbara Tuchman, so that they would be better informed about the history of WWI and be able to avoid the same mistakes. This book is often criticised by modern historians but it easily still outsells many more recent works.

President Carter sees the League of Nations as a positive development of WWI, and eventually we had the United Nations, after WWII, as an attempt to avoid wars.

On political leaders, Carter contends that certain leaders of the WWI era saw war as a way to exert their political influence and perhaps territorial expansion. They thought they could go to war with impunity and win without the danger of loss.

His hope for the book is that one can learn some lessons on how to avoid a future catastrophe.

In the book itself, the question is whether WWI was a logical response to the political conditions in Europe in 1914, or rather a reaction against, and a break with, them. So, the issue is the degree of probability and inevitability in the outbreak of the conflict.

One aspect is whether WWI was caused by a series of serious professional mistakes by a comparatively small group of diplomats, politicians and military leaders, or is it an automatic outcome of the mind-set of the European generation of 1914? It was a common suggestion of many writers in the 1990s that European societies and their governments, in the summer of 1914, were filled with suicidal enthusiasm for the incipient conflict. However, much new research in recent years has successfully challenged that view. The current view suggests that public opinion in the belligerent countries was highly differentiated by region and by social class.

The book seeks to provoke a corresponding reappraisal of how the European political culture before 1914 dealt with the question of war and peace. First, the book seeks to cover not only the culture of individual states but also pan-European themes such as the rules of diplomacy, honour, gender, religion, and the arts.

So, in the first chapter Paul Schroeder contends that WWI was ultimately the outcome of changes in the unwritten rules, or norms, of the international system. The ever increasing brutality of these rules placed enormous pressure on some members of the international community, robbed them of breathing space, and ultimately forced them into suicidal action. According to Schroeder, Austro-Hungary may have become a perpetrator, but it was also a victim. In effect, he suggests that war was essentially unavoidable by 1914.

Next, Matthias Schultz looks at European congressional diplomacy between 1815 and 1914. He contends that even at the end of this period, adequate peacekeeping mechanisms existed, and that the Austro Serbian crisis could have been resolved by a conference or by a multilateral peacekeeping effort, instead of a forceful and unilateral Austrian action with German support. As the international system lost ethical foundation, war became more probable. Schultz characterises the Hapsburg monarchy, from a statistical analysis of the incidence of crises, as the leading fomenter of instability in Europe. He therefore disagrees with Schroeder who sees Austro Hungary as a great victim of the international system.

Samuel Williamson also looks at the situation in Vienna. He analyses the decision making process of Austro Hungary during 1914. His chapter shows that the Hapsburg political elite had not resolved the question of war against Serbia even before the Sarajevo assassinations, and that they had other political priorities. Thus, the Sarajevo assassinations became the decisive moment, in that without the murder of France Ferdinand and his wife, there would have been no decision by the Austrian government for war with Serbia. The author contends that German pressure was not decisive, and that the Hapsburg leaders made their own decisions.

John Rohl provides a powerful analysis of Wilhelm II and his political line, personal goals and responsibility during the July crisis. He believes that the German leaders deliberately started the war and traces the roots of the conflict to the German political system and the personality of the German ruler, whom he indicts for his duplicity and recklessness.

Jost Dulffer discusses the two Hague peace conferences and their attempts to limit the level of armaments and to outlaw the use of certain weapons. Alternatives to the existing European balance of power system, with its adjustment mechanisms of arms build ups and deterrence, had no chance of making headway in an era when every state was keen on keeping control over its own sovereignty, including the right to configure its armed forces in the light of its own strategic planning and perceived security needs. There was a third peace conference envisaged for 1915. Had not war intervened, the momentum in favour of arms control and international arbitration might have developed further.

Michael Epkenhans analyses the Anglo German naval race, showing how Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, Secretary of State of the Imperial German Naval Office, overcame all internal resistance to his fleet building programme. Unquestionably, the naval rivalry poisoned Anglo German relations. However, by 1914 the most acute phase of the naval race was over and the British had won it, not least because Tirpitz and the German Navy had run out of money. Although the naval rivalry contributed to the deterioration of the international situation, and especially to Germany’s place within it, it did not in itself trigger the outbreak of the war.

Similarly, in his discussion of the land armaments race David Stevenson confronts directly the question of whether or not the world war was improbable. He argues that land armaments competition indeed destabilised European international relations, but that the leaders of the powers could have found peaceful solutions to their security predicaments. Earlier arms races had ended without hostilities and the pre-1914 race, although a critical danger to European peace, might have evolved into a non-violent confrontation or “cold war”.

The essay by Gunther Kronenbitter investigates the war planning of Helmut von Moltke the younger and Franz Conrad von Hotzendorf, the German and Austrian general staff chiefs. Both men agreed that the impact of a large scale continental war would have devastating repercussions on European civilisation for decades. They also recognised the unpredictability of the outcome of such a conflict. Yet precisely because they were trapped by their understanding of national and personal duty, they prepared for a war which they thought would inevitably be a disaster for Europe and for their countries. Whilst neither chief had the authority to initiate a war, their narrow understanding of military security subjected European peace to an enormous structural burden. In other words, although developments in armaments policy and in strategic planning did serve to endanger peace, they did not so destabilise the international order as to make war unavoidable.

Holger Afflerbach addresses the central themes of the volume by analysing the expectations about war current among the European governments of 1914. His basic contention is that, if contemporaries had really believed war to be unavoidable, then everyone would have expected that after Sarajevo events would lead quickly to the outbreak of hostilities. But in fact the opposite was true. The elites of the era did not believe that a Great War was probable and they were completely surprised by its outbreak. The notion that nobody would risk such a devastating catastrophe was all the more widely accepted because of the highly developed system of deterrence of the day. Afflerbach therefore denies that European societies of the day expected a cataclysm, contrary to the thoughts of earlier historians. He also discusses the various military leaders who dreamed of a great European war out of self-indulgent motives, but he suggests that even they believed that such a war was both improbable and liable to be immensely destructive. However, the danger in this situation was that some statesmen were so confident that a Great War was impossible that they planned their actions without the necessary caution. The war was therefore improbable because it went against the tides of that time. The actual outbreak of war was even a consequence of the misplaced confidence that peace was secure.

Friedrich Kiessling pursues a similar line of argument in his analysis of policymakers conduct during the diplomatic crises of the years leading up to 1914. He insists that in trying to explain the war’s origins it is a mistake to focus only on those factors which seemingly lead to an escalation of international tensions. He looks instead at efforts to achieve detente and de- escalation in political conflict. Paradoxically, this policy of seeking détente may have been too successful, leading to miscalculations by some of Europe's leading statesmen in the July crisis. Because compromise had been achieved in previous crises and war had repeatedly been averted, the assumption may have been that in 1914, too, conflict could be avoided. The mind-set of “improbable war”, or of dangerous faith in détente, made key decision makers perilously insouciant. For both Afflerbach and Kiesssling, the outbreak of war in Europe was a consequence of carelessness caused by overconfidence, comparable to the complacency of the crew of the Titanic who failed to reduce their speed at the moment of danger.

Roger Chickering analyses the popular mood in the summer of 1914, focusing his attention on the middle-sized German city of Freiburg. It is a combined general survey of the public opinion literature, with an interesting case study. He adds:

"the dramatic scenes of the summer of 1914 ought to be understood in the light of their own political and cultural dynamics. They should not be taken as evidence that an inveterate German war enthusiasm made war probable or inevitable.”

Consequently, his contribution weakens the hypothesis that WWI was unavoidable.

The next chapter, by Joshua Sanborn, deals with developments in Russia, again with reference to the question of whether the political culture in this country made the Great War probable or not. His complex arguments show how difficult it is to find clear and simple trends in pre-war societies. He discusses the evidence for growing popular patriotism and militarism in pre-1914 Russia, as in other European countries. Examples include the celebration of the Franco-Russian alliance, government-led centenary commemorations of the victory of 1812, the abolition of schoolteachers’ exemption from conscription, changes to the school curriculum, and the creation of new patriotic societies. On the other hand, he also demonstrates the reservations felt about these developments on the part of pacifists and of authoritarian conservatives, including the Tsar. Yet, he concludes that a particular form of patriotism, that is a deep concern for Russia's status as a great power, was decisive in hardening policy in the July crisis and impelled decision-makers to opt for a war that no-one regarded with enthusiasm and was widely considered to be highly inopportune.

There are chapters on the roles of culture, religion and gender in international relations before 1914, as well as to the topic of internationalism as an influence on the question of European peace. In particular, Ute Frevert in her essay states that gender-related understanding of honour in European societies had a distinctive influence on the events of summer 1914. In short, she refers to manly posturing which made attempts to peacefully solve the crisis extremely difficult.

The last three chapters describe the view from afar. Ottoman Turkish politics and their view on Europe are analysed in a chapter by Mustafa Aksakal. He draws on newspapers and other publications to demonstrate that the Ottoman leaders felt they were victims of the international system. They actually hoped for a war in order to be saved from their difficulties. From their perspective, a local war was not only probable but also desirable. The Young Turks dreamed of a war of liberation and independence and they were eager to secure German help for it. The ultimate goal was to stabilize the Turkish international position and to halt its secular decline. However, it is likely that the government in Constantinople neither envisaged nor predicted a general European war, although when this event occurred it was perceived as a great opportunity.

Fred Dickinson analyses reaction in Japan to the war in Europe. His essay shows the surprise felt in Japan when WWI broke out. Once war had broken out, Japanese newspapers and political commentators looked for explanations and found them in the materialistic European culture, in the instability of the balance of power, and finally by conceiving of the war as a racial struggle. In addition to the general explanations, Japanese commentators tended to see Germany as being primarily responsible for the catastrophe. The author also identifies a Japanese culture of profiting from turbulence in Europe in order to make opportunistic gains in East Asia.

The final chapter by Fraser Harbutt examines the perspective of the United States. Americans were generally shocked and surprised by the outbreak of the conflict. It seemed to be an act of European suicide which they had not previously considered to be possible or probable. Developments during the first few months of the war had already made it likely that American neutrality would be pro-Allied and that the US would eventually intervene against Germany. The views from afar demonstrate again that many contemporary observers from inside and outside Europe did not foresee the conflict and that they considered it as a highly improbable event.

All the authors acknowledge that the international system before 1914 was endangered by several developments, prominent among which were armaments competition in the single-minded military understanding of national security. So, was the war unavoidable? Well the authors are rather divided on that. However, WWI did mark an abrupt departure from previous trends in European political culture, not their continuation or automatic outcome. The consensus is that WWI was not inevitable. In the words of a pre-1914 French school book "war is not probable, but it is possible."

Overall, this is an excellent and wide ranging analysis of the factors behind the defective decisions made by many governments in the July crisis. It is to be highly recommended.

- Details

- Category: Book review

Book Review

A Naval History of World War I

Paul G Halpern

Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1994

Professor Halpern is an American academic historian who spent all his career working on the naval aspects of WWI. Unlike some British historians whose myopic view of the naval aspects of WWI is confined to the Battle of Jutland, maybe even stretching as far as other parts of the North Sea, Paul Halpern’s vision is truly global. I do not know of any other work which comes close to the breadth and authority of this book.

The Navies

The author deals with matters chronologically, as might be expected, starting off with the pre-war naval arms race, and goes rather further than the usual Royal Navy versus Germany account.

At the outbreak of the war, the Royal Navy was in the lead, worldwide, with 22 dreadnought battleships in service and a further 13 in construction. The equivalent figures for the German navy were 15 dreadnoughts in service and 5 being built. The RN crews were volunteer and tended to serve for long engagements, whereas the German crews were conscripts who served for only three years. The RN was involved in protecting the Empire, though much of that work could be done by the numerous older warships. Germany did, of course, have some colonies in this era but nothing as extensive as Britain’s colonial holdings. Germany also had to face off with the Russian fleet in the Baltic, and do not forget that the German coastline included much of what is today Poland and Kaliningrad. However, they could move even dreadnoughts through the Kiel canal, thus avoiding the journey round the north of Denmark.

The French were the pre-eminent force in the Mediterranean. They were concerned with the protection on their colonies in North Africa and the ability to transfer troops to France from North Africa in the event of a European war. In August 1914, the French navy had two dreadnoughts in service, with another two on sea trails, 84 destroyers and 67-75 submarines.

The Italian navy, the Regia Marina, was undergoing a shipbuilding programme and had three dreadnoughts at the start of WWI. The aim was to have 60% equivalence to the French and a 4:3 superiority over the Austrians.

The Austro-Hungarian navy is now long forgotten, but in 1914 it was a decent, middle-ranking navy based in ports along the Adriatic, with three dreadnoughts and three semi-dreadnoughts. One issue in 1914 was which side the Italians would be on in WWI, and therefore whether the Austrians and Italians would be on the same side, or opposite sides. The Mediterranean had a delicate balance of naval power between three navies resident there, and the RN based in Gibraltar and Malta, safeguarding the route to the Suez Canal and, ultimately, to India.

Matters further east were somewhat more on edge as the Greeks and Ottoman Turks had fought two Balkan Wars. Matters were pretty even, but the Ottomans “bought” two ships from Germany, the Goeben and Breslau. However, once the war was underway, much of the Entente interest was in the Greek small craft, which could be deployed against enemy submarines.

The Russian navy was still recovering from the catastrophe of the Russia-Japanese war of 1905. They also had to split their navy between the Baltic, the Far East and the Black Sea. There were plans to build new ships but the picture for the Russian navy was that it had a lot of potential, much of which failed to materialise.

The United States Navy was also in the “having potential” category but in this case, it would be fulfilled. Even so, in 1914 the US Navy had 10 dreadnoughts with a further 4 in construction. The US Navy was already a powerhouse, which the US army certainly was not at this stage. The US Navy would play a vital role, when the US entered the war, in protecting convoys from submarines and surface raiders.

The Japanese navy, which would do sterling work in the Mediterranean, started in 1914 with two dreadnoughts in service and another two in construction. The Japanese also started an ambitious programme for building new destroyers, which were to be invaluable later in the war. The Japanese saw action early in the war against the Germans in the Pacific.

The USS Texas - the only surviving WWI dreadnought

The Early Part of the War

The author explains that, at the outbreak of WWI, the naval generation that had experienced the naval arms races, read The Riddle of the Sands with its theme of a German seaborne invasion, and been observers of the Japanese attack on the Russian base at Port Arthur in 1905, fully expected a naval engagement or invasion attempt in the first 48 hours of the war. In fact, of course nothing major happened in the North Sea for two years.

Close coastal blockades were recognised as now being impracticable due to the developments with better mines, submarines, torpedoes, and long-range coastal artillery. So, blockades had to be set up some considerable distance from the coast, which increased the length of the picket line. In 1911, the British recognised that a future war would now involve, primarily, the army being sent to the continent, not an attack by the RN on the German coast or navy. This rather negated the 1914 German naval strategy, for there would be no enemy off the coast to attack. It is also often overlooked that the French had sizeable numbers of sub-dreadnought warships in the North Sea and the Channel.

The author goes on to deal with the Mediterranean theatre, a topic in which he is the expert. The French were anxious to maintain their dominant position, for they had to transport their troops from their North African colonies to France itself. Italy was neutral until 1915. It has a long and vulnerable coastline. In the Adriatic, the Austro-Hungarian navy was able to keep the French navy out by the use of submarines and mines. The Adriatic is more confined than the North Sea, and the various forces are closer together. The Germans reinforced the Austrian submarine force, initially by sending disassembled submarines by land but later sending better submarines by sea into the Mediterranean past Gibraltar. The British and French created a barrage in the Straits of Otranto to keep Austrian ships and submarines bottled up in the Adriatic, with success as regards surface ships but little against submarines.

The book then deals with the defence of allied trade throughout the world. This includes the somewhat romantic but ill-fated voyages of the Emden and von Spee’s fleet from Tsing Tao to the battles of Colonel, off Chile, and of the Falklands. There is mention of the Dresden meeting up with von Spee’s force at Easter Island, which does seem to be a bizarre event in a very remote corner of the Pacific. (If your geography is not up to it, Easter Island is 1,200 miles even from Pitcairn Island, which is itself pretty remote). There was no use of convoys for merchant ships at this stage of the war, but they were indeed used for troopships taking soldiers from Canada, India, New Zealand, Australia and India. In many ways, these convoys were the non-story, as no Allied ships or troops were lost due to enemy action at this stage of the war.

The author details the various madcap plans hatched by Churchill for attacks in the North Sea and the Baltic. Some of these involved taking Danish, Dutch, Swedish or Norwegian territory, all of which were neutral. Attacks on the German islands of Borkum and Helgoland were mooted but, in the end, planning for the Dardanelles attack in 1915 prevailed. This was the idea that warships could blast their way through to Constantinople and force the Ottomans to surrender. This did not succeed, and the campaign mutated into the Gallipoli landings. There, the German submarines played a key role in keeping the Entente ships at bay, though British counter measures by using small craft and boom defences were partially effective. The British and French did use their own submarines against Ottoman warships, with some success.

The Baltic had a fascination for the RN, though the realities of access through the narrow waters between Denmark and Sweden meant that there was a likelihood of severe losses for little return. However, two British submarines did manage to make it into the Baltic, where they operated with the Russian navy. The Russians had a lot of territory to defend, as Finland and the Baltic states, as they now are, were all part of the Russian Empire. Mine laying was a key feature of the naval operations in the Baltic.

The naval hostilities in the Black Sea, between Russia and the Ottomans petered out with the 1917 Russian revolutions, as indeed they did in the Baltic.

A truly forgotten campaign

However, perhaps the least remembered naval campaign of WWI is that on the Danube. This river flows from Germany and ends up in the Black Sea. It was navigable from there as far as Galatz in Romania. It was, and is, an important commercial route through central Europe. At the time of the Gallipoli campaign, the Danube was a potential supply route from Germany to Turkey.

The Austrians had six monitors in service at the start of the war, and added four more. There were also six small patrol boats and others were added during the war. Most of the contribution to the war effort of the Danube flotilla was in providing artillery support for the army. The anticipated battles with the Romanians or Russians never happened. However, three Austrian monitors fired the opening shots in WWI on July 28th 1914 when they shelled Serbian fortifications on the railway bridge on the Belgrade to Zemun line. The author writes:

It was, and remains, difficult to think of Belgrade and the Danube as more than a secondary front in a largely forgotten campaign of the Great War. But it had the potential to be far more important.

With the Entente blocking the Dardanelles and Romania being neutral, there was the possibility to transport supplies from Germany to Turkey. The Serbs still controlled Belgrade, so any attempt to do so had to run the gauntlet of their defences, at least until such time as they were pushed out of Belgrade. There was even a British naval mission to support the Serbs. A picket boat was transported by rail from Salonika to Belgrade. It was facetiously dubbed The Terror of the Danube. In its one operation, it seems to have fired torpedoes at two dummy craft that the Austrians had constructed.

The big show

In 1915-1916, the Germans were searching for a strategy to counter the Royal Navy. The ideal forum from the German viewpoint was those waters of the North Sea which they could reach in a day or a night, and where they could bring their maximum strength to bear. They would be much closer to their bases than the RN would be to theirs, and damaged German ships had a much better chance of making it home than the British ones would do. The approach of using maximum strength could lead to success, but also to heavy losses. However, the British did not have to engage in any such battle – they could maintain their distant blockade. The Germans would have to come to them if they wanted to break the blockade.

The success of the German submarines was something of a surprise to the German naval establishment who, like the British, initially regarded them as an adjunct to a high seas fleet, not as an independent force in their own right. However, the RN was so concerned about the danger of submarines that the Grand Fleet sheltered in Lough Swilly in NW Ireland and also in Loch Ewe in NW Scotland, until the defences at Scapa Flow could be improved.

The conquest of Flanders enabled submarine bases to be set up at Brugge, with outlets at Zeebrugge and Oostende.

The Germans expanded their targets for their submarines from warships, which they would struggle to locate, to merchant ships, in effect in retaliation for the RN blockade. A key issue was neutral ships, especially those sailing to or from British, or indeed American ports. There was also the situation that the over-hyped British “Q” ships had used neutral flags.

Inevitably, neutral ships were sunk and lives were lost. There was friction with the Netherlands over two of their ships which were sunk, going between neutral ports. The sinking of the Lusitania caused, of course, the major diplomatic incident with the United States. The Germans then managed to sink more Dutch ships, including passenger ones, to the anger of the Dutch government and press.

The intense internal discussions as to the future strategy of the U-boat campaign in the German political and naval elite are laid out in detail by the author.

The Battle of Jutland and its consequences are dealt with in detail in the book. One later consequence of the problems of Jutland, in the run up to WWII, was that the plan to name two new battleships Jellicoe and Beatty was changed in favour of the less controversial Anson and Howe. The common claim that the German High Seas Fleet did not emerge again after Jutland is quite simply wrong. For details, see chapter 10 of the book!

The light cruiser HMS Caroline, the only survivor of the Battle of Jutland, now a museum

U-boats

In October 1916, the restricted U-boat campaign restarted. Incidentally, the account of the sinking of the Arabia is incorrect. The correct version is given in Joachim Schroeder’s book The Kaiser’s U-boats, which was based on detailed analysis of the German naval archives but which, in fairness, would not have been available to Halpern when his book was written. In fact, the Arabia tried to ram a U-boat which was on the surface having stopped a merchant ship under cruiser rules. The U-boat turned through 1800, dived and fired a torpedo.

The author goes into the unrestricted U-boat campaign of 1917, pointing out that a major factor in the German success was, quite simply, more U-boats. However, not all were sitting in the North Sea and eastern Atlantic. Of the 105 U-boats available on the 1st February 1917, the High Seas Fleet had 46; Flanders bases 23; Mediterranean 23; Kurland (Baltic) 10; and Constantinople 3. More boats were ordered in the middle of 1917 but there was severe doubt as to when they would be built. The year 1917 was the peak of U-boat success. It did have the feared effect of bringing the United States into the war.

The counter measures thought up by the Entente included the rather inept Dover barrage which sought to keep U-boats from transiting the Channel, and the truly megalomanic North Sea minefield between Scotland and Norway (with acknowledgment to Alex Watson for his description of the latter device). The big success, however, was the convoy system. It had its enemies in the RN and merchant navy establishment, indeed for much of the war. The objections which the author describes include that: it made ships more vulnerable to attack because they were bunched together; there would not be enough escort ships; the ships could not zigzag; there would be congestion in the ports which would decrease the available tonnage of ships; and masters would not be able to keep station. An analysis by the RN after WWII concluded that none of the objections raised was valid. Consequently, use of the convoy system greatly reduced losses in WWI, and, as we know, convoys were used in WWII (which is Rob Thompson’s criterion of whether a WWI tactic worked or not).

There were still those in the RN, and indeed the US Navy, who thought they should be conducting “offensive” actions against U-boats. This manifested itself as operations to hunt enemy submarines using hydrophones. Neither the hydrophones nor the “hunts” worked. They only served to distract from the more important task of guarding convoys.

The role of the US Navy is well covered, not surprisingly for an American author (and indeed the Japanese naval contribution gets an honourable mention too – amongst other deployments, Japan sent 14 destroyers to the Mediterranean in 1917). Much of the US Navy focus would be on protecting the troop ships coming from the US to Europe. Admiral William Sims sailed incognito to the UK on 31st March 1917. He signalled back to Washington that the situation was much worse than they had believed and that urgent naval assistance was required to deal with U-boats. So, six US Navy destroyers left Boston on 24th April 1917 under the command of Commander Joseph Taussig to go to Queenstown (now Cobh, near Cork in SW Ireland). They arrived on 4th May, having had a pounding crossing the Atlantic, and consequently had a long list of defects. When asked by the C in C Ireland, Vice Admiral Lewis “Luigi” Bayley, how long he would need to get his destroyers ready for sea, Taussig replied:

“We are ready now, sir, that is as soon as we finish refuelling. Of course, you know how destroyers are – always wanting something done to them. But this is war, and we are ready to make the best of things and go to sea immediately.”

Bayley gave them four days. Sims was alarmed when he heard nothing about more destroyers being on their way and signalled Washington to that effect. He was relieved to hear that 36 more would be sent. By the end of August 1917, there were 35 US Navy destroyers based at Queenstown.

Being a bit late into the game, as it were, the US Navy Department were slow to catch on to the importance of convoys.

The convoys had major warships as ocean escorts, and then needed destroyers or smaller craft to meet them when they entered the danger zone for submarines, off the coasts of the UK (including, of course, Ireland). As well as the US Navy destroyer presence at Queenstown, there were RN escorts at Buncrana on Lough Swilly in NW Ireland. By 1918, there were convoys from the US to Brest in France, with French naval ships providing cover.

The U-boat commanders were hard pressed to find convoys, and the presence of major warships precluded surfacing and using their deckgun, which would still have been the predominant form of attack. The success of the convoy system led the German naval command in October 1917 to switch U-boats to coastal waters, where ships might still sail singly. The British instituted coastal convoys and ports of refuge in response. By the end of 1917, the Entente was getting on top of the U-boat problem.

Surface Raiders

German surface raiders had a sort of swashbuckling charm and caused a lot of Entente naval activity in trying to find and attack them. The Möwe, disguised as a Swedish steamer, left Kiel on 26th November 1916 for a four-month voyage. A subsequent WWII analysis of the damage she inflicted, and the Entente efforts to deal with her, concluded that both could have been improved considerably by an earlier introduction of the convoy system. Trying to locate surface raiders without air cover, as was the case in WWI, is looking for a needle in the vastness of the ocean. The Mȍwe and two other surface raiders roamed as far as the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. However, their efforts paled into insignificance when compared to the amount of shipping sunk by U-boats.

Mediterranean

The author is an authority on the Mediterranean theatre in WWI. The first German submarines were sent there in 1915 in response to the Dardanelles campaign, and the fact that the Austrians lacked the modern submarines to operate that far from the bases in the Adriatic. One bonus of the theatre was that there was very little neutral shipping, so the chances of a diplomatic faut pas were lower than in the Atlantic. As well as Gallipoli, the Salonika campaign was starting in late 1915. All of this necessitated transportation of troops, both British and French, and consequent escorting of the troopships to deter U-boat attacks. There was a shortage of warships, so patrol zones, where there was a heightened likelihood of U-boat attack, were devised. The patrol zones were divided between the British, French and Italian navies. The Entente Otranto barrage, in reality a picket line, failed to keep enemy submarines bottled up in the Adriatic where they were based at Pola and Cattaro. Inevitably, convoys had to be introduced in the Mediterranean.

In 1917, the Japanese sent 14 destroyers to the Mediterranean. The convoy system was reorganised in late 1917. The US Navy sent ships to the Mediterannean in August 1917, including three light cruisers, six old destroyers which came from the Philippines and a variety of small craft. Another navy which joined the Entente effort in the closing days of the war was a squadron of the Brazilian navy. The Americans also deployed so-called “submarine chasers” which were 75 ton, 110 feet long, wooden hulled launches. Although they claimed 19 “kills” during their deployment, the truth was that they failed to achieve a single kill.

The end: the submarine threat contained

At the end of 1917, Beatty’s analysis of the situation was that a great danger was a break out by the German High Seas fleet, which made him fearful that the RN had the resources to deal with it. However, in December 1917 the US Navy sent a battleship division to Scapa Flow which included five dreadnoughts, further strengthening the Grand Fleet.

The Dover Straights patrols and picket line of small boats was reasonably successful in preventing the bigger U-boats from accessing the Channel. On 14th-15th February 1918, a German destroyer force attacked the Dover Patrol, as it was known, with fair success. One unbelievable incident was that two groups of RN and German destroyers sailed past each other in the dark without firing. The captain of the last British destroyer, who signalled the German destroyers but did not open fire when he had no reply, was later court martialled and relieved of his command.

The Zeebrugge and Oostende raids are dealt with in the book. There is a wonderful quote as to the reason why a naval bombardment was not used instead to attack the lockgates – in essence, it would have necessitated hitting a target that was ninety feet long and thirty feet high from a range of thirteen miles, whilst under bombardment by the German shore battery. Ultimately, the Flanders U-boat bases failed to live up to their potential throughout the war.

The last hurrah of the German High Sea Fleet

Although German operations in the first three months of 1918 centred around submarines or smaller ships, there was the constant concern on the part of the British that the German High Sea Fleet would break out, destroy the Dover Patrol, and disrupt shipping between Britain and France. The Royal Navy were able in April 1918 to move the Grand Fleet from Scapa Flow to a new base at Rosyth, outside Edinburgh, where it was better placed to deal with a southerly incursion of the German fleet.

In fact, the Germans planned to attack the Scandinavian convoys, as they had done previously in November 1917 with considerable success, which was a factor in Jellicoe’s sacking. This time the full might of their High Sea Fleet would be deployed to back up their cruisers and destroyers, and be able to deal with any threat from the dreadnoughts of the RN or US Navy. So, they set sail on 23rd April 1918 from the base at Schillig Roads, near Wilhelmshaven, observing radio silence. High winds prevented them using airship reconnaissance. The Germans headed for the coast of Norway to wait for a convoy. However, Scheer had acted on faulty intelligence, deduced from radio traffic and U-boat reports. In fact, there was no convoy off the coast of Norway for them to attack on that day, going either east or west. One battleship, the Moltke, had a major breakdown and the entire fleet then limped home. It was also the American – German engagement that did not happen, as the American battle group had been providing back up for the Scandinavian convoys during the previous week. This was the last time the German High Sea Fleet would go to sea in strength seeking battle.

As convoys were being used on the high seas, U-boats changed tactics and concentrated on coastal waters around GB and Ireland, eventually necessitating the formation of convoys even in coastal waters. This was not a glamorous aspect of the war at sea, but an important step nonetheless.

Air surveillance

Aircraft and airships were increasingly deployed on anti-submarine duties. By the end of the war, the British had 557 aircraft on anti-submarine work in coastal waters. The US Naval Air Service by that stage had 400 aircraft and 2,500 men in Europe. They operated a base at Killinghome on the Humber, had four airbases and a kite balloon station in Ireland, with more bases in France and on the Adriatic. The French also made extensive use of aircraft on coastal operations, mostly in the Mediterranean and the Adriatic. The abilities of aircraft in WWI were limited to spotting U-boats on the surface. They did not have the lift capacity to carry any munitions that would “kill” a submarine.

Transportation from the US

The US used major ocean liners for troop transportation across the Atlantic. As well as huge capacity, they had a good turn of speed and could certainly outrun U-boats. The really large movements of US troops to Europe began in April 1918. There was concern about German surface raiders attacking the troop convoys. To afford protection, the US Navy sent a battleship division, which included three dreadnoughts, to Berehaven in SW Ireland, a RN naval base, to guard the Western Approaches. There was, thus, a huge, and now largely forgotten, US naval presence in SW Ireland in the last 18 months of the war.

So, the Atlantic Bridge was a major success, both in terms of material and men. Perhaps the most apt example of this success is a quotation in the book from an RN sub-lieutenant who was making his way home in October 1918 through France, from Gibralter:

The chief cause of our delays were the movements of huge numbers of Americans across France. In fact, we scarcely saw any Frenchmen in the country. All the soldiers were Americans, and more than half the rolling stock and Red Cross trains were also from America. The whole of France seemed to have been bought up by the Yank. He had built his own camps, railways, stores, everything. It was a pity some of the German submarine commanders could not see the stuff that was slipping by them.

As the author says, there could be no clearer testimony to the final failure of the U-boat offensive.

The final word

Overall, this book must be the bible of the naval aspects of WWI. It is truly a master work by a world expert. The downsides are, firstly, that there are no photos of any sort, which is a function of the era in which the book was published; and secondly that the maps are stuck at the end of the book. They would have benefitted from shading to make them more intelligible. As far as I can see, the book is still in print, but you may have to deal with Abe books, or whoever, to track down a copy. It is highly recommended.

- Details

- Category: Book review

On a Knife Edge

Holger Afflerbach

Verlag CH Beck, Munich, 2018

This is indeed a book review, but given that the book itself is in German and therefore not easily accessible, this review gives a more detailed account than would normally be the case.

Holger Afflerbach is the Professor for European History in the University of Leeds. He is German, and the book is indeed in German – its proper title is Auf Messers Schneide.

In this book, he looks afresh at the conduct of the war, the politics of it all, both national and international, and the state of the home front in Germany. In doing so, he debunks some myths and misconceptions, and provides new insight into the reasons that the war continued for as long as it did.

The book starts with an analysis of pre-war European politics. There was a general belief that in any future war there could not be a victor as such – that a war between the Great Powers would be suicidal for all of them. However, Germany saw itself sandwiched between Russia to the east, and France and Great Britain to the west. There was confidence bordering on arrogance as regards its military capabilities, having defeated Austro-Hungary and then France in the 19th century. The German public had a pride in its armies and faith in the military leadership. All had confidence in the military superiority of their country.

Norman Stone has said that, like all the other armies in Europe, the high command did not comprehend how the impetus in warfare had moved from offence to defence, due to the introduction in the 1880s of ammonium nitrate based explosives, quick-firing artillery such as the French 75mm, and the Maxim-patent machine gun.

The Schlieffen plan was von Moltke’s attempt to knock out France before engaging Russia. Afflerbach points out that it was only in 1912 that General Joffre decided that French war plans should not include invading Belgium and Luxembourg. A French historian has written that France won WWI in 1912, as an invasion of Belgium would have alienated both Great Britain and the USA. In the event, Russia beat everyone to the starting gate, and invaded German territory in East Prussia before any German soldier set foot in Belgium.

Hindenburg was brought out of retirement to nominally lead the campaign in the East. In fact, Ludendorff was the military brain but he had no charm or PR appeal. Hindenburg became the “saviour of Prussia”, as he was given the credit for pushing the Russians out of East Prussia, and a popular figure in Germany as a result. At the end of the war in 1918, as things were collapsing in Germany, Ludendorff was sacked and did a runner to neutral Sweden, disguised as a diplomat.

The myth of the victory at Tannenberg in August 1914 was Hindenburg’s creation. It was, in fact, a late suggestion for the name of the battle, which was actually at Allenstein, some 30kms from the site of the 15th century defeat of the Teutonic Knights, for which it was supposedly vengeance. (One earlier, unmemorable, suggestion for a name had been the Battle near Gilgenburg-Ortelsburg).

The scenario on the home front changed from 1914/15, where there was optimism about a great military victory, to 1917 where the effects of a coal and food shortage lead to the “turnip winter”. This change of mood is well illustrated in the book by contrasting Christmas “selfie” photos of the Wagner family in Berlin in 1915, with plenty of the table, to 1917 where they are wearing overcoats indoors.

Photo above: the Wagner family in Berlin at Christmas 1915. The map behind them shows the Western and Eastern fronts, far into foreign territory. There is a rather immodest display of the family’s possessions including fancy gloves and plenty of food.

Photo above: the same scene at Christmas 1917 with the coal shortage during the “turnip winter”. There is still a pretentious display of their possessions but less impressive than before, with less food on the table, and of course they are wearing their overcoats indoors.

Strikes grew more numerous. In 1915, there were 42,000 strikers but in 1916 this figure grew to 245,000. This is an indication of increasing social unrest and dissatisfaction.

Ultimately, there was increasing unrest by autumn 1918, leading to the November revolution in Germany. Incidentally, the downfall of Kaiser Wilhelm seems to have been almost accidental, as the American view was that he could remain as a monarch in the British mould, with no political power.

The unrestricted U-boat war from 1917 is analysed in the book. It was, in fact, a populist move, much like some of the simplistic policies of US President Trump, or indeed closer to home, that are supposed to solve everything but in reality solve nothing. Those who understood the naval situation were convinced that it could not succeed and they were right: the pressure for the offensive came from the public and the army, not from the navy. The fear was that such a move could bring the USA into the war, which indeed it eventually did. Such a move could paradoxically improve Great Britain’s supply situation, as the USA would go all out to keep Britain supplied.

Professor Afflerbach’s analysis of the figures for the unrestricted U-boat war does cast matters in a more informed light than is often the case. If the tonnage sunk is broken up and expressed per U-Boat or per day of deployment, then the figures for ships sunk are only marginally higher than previously. Indeed, in the Mediterranean the figures were actually lower. The point is that there were more U-boats deployed, not that the tactics made much difference. One of the problems for the U-boats was finding targets. The use of a wolf pack, as happened in WWII, was not feasible, as you need long-range aerial reconnaissance to locate the convoys and transmit that information to the U-boats, which also implies good radio communications. So, in WWI the U-boats had to hang around the shipping lanes, typically the approaches to major ports. For example, the locations of ships sunk by U-boats off the Welsh and Irish coasts are clustered around the ports such as Holyhead and Dun Laoghaire (Kingstown in that era).

The unrestricted U-boat campaign put an end to the peace discussions that had been going on since late 1916. The war positions of the various protagonists were disparate and complex. A very real fear of some in the German leadership was that Russia would disintegrate into chaos of a communist revolution sparked from within, and that would generate mass unrest in Western Europe. The decision, or lack of decisiveness, to let the war continue into 1917 and beyond was to let Europe glide into a catastrophe. The consequences were a dysfunctional post-war order, communist and fascist dictatorships, the “bloodlands” of eastern Europe, a second world war, and the cold war. A compromise peace in late 1916 and early 1917 could thus probably have avoided the subsequent catastrophes of the 20th century.

France and Italy had clear, nationalistic, albeit destructive, war aims. The British war aims were more nebulous. Certainly, both the British and the French had their eyes on new colonies at the expense of the Ottomans, as evidenced by the Sykes-Picot agreement. A central war aim was to put Germany in its place. In other words, the British saw the conflict as a return of the Napoleonic Wars and a struggle to restore the balance of power in Europe. The belief was that could not happen until Germany was defeated, and a negotiated settlement would not do that. The comparison was with the negotiated peace agreement signed in Amiens with Napoleon in 1802, which only lasted a year. However, the continuation of WWI put Britain and France into more debt to the USA and bolstered the USA’s position as a centre of world finance, which continues today. Lord Lansdowne was one voice who sought compromise. On the other hand, the cabinet of Lloyd George saw things as a military issue, not as a political one. Perhaps this was a common failing of British governments throughout the 20th century?

The “victory” which the Entente of 1916 sought was ill-considered goal setting. Neither the collateral damage that was to ensue, ie hundreds of thousands of deaths, was brought into consideration, nor how to bring about a functioning peaceful framework. This only changed with US President Woodrow Wilson’s “peace without victory” and his fourteen points.

This brings us to the key problem of dealing with the Entente – it was a coalition. So, who can you negotiate with? That issue was only resolved in 1918 when the USA came into the war openly, and President Wilson was seen as the man in charge. However, the Kaiser Schlacht offensive of March 1918 was a major obstacle to negotiations at that stage. Then, in October 1918 the sinking of the RMS Leinster between Dublin and Holyhead with the loss of 567 lives hardened President Wilson’s position. (My goodness – an historian who has actually mentioned the Leinster). By 1918, of course, Russia was out of the war and in a civil war, with which the Entente were interfering, remarkably unsuccessfully. Communism was seen as the rampant danger which would “infect” the populations of the West.

A key component of Wilson’s plan was self-determination for national groupings. Indeed, one of the suggestions inside the German government earlier on in the war was to allow the population of Alsace and Lorraine to have a vote on which country they wished to belong to. The problem there is that there would have been consequences for other regions, especially Poland. At one stage, the Germans sought to raise a Polish Legion to help fight the Russians, with little success. But, once you have recognised the Poles as a national group how can you not give them a vote on their future? Where would the territory for this new Poland come from? It could not all come from Russia. Austro-Hungary had a large Polish population, predominantly in Western Galicia, which presumably would have to be given up. In Germany, there was a significant Polish population in part of East Prussia, which is where Falkenhayn, Luddendorf and Hindenberg came from. So, could you cede the homeland of your politico-military leadership to form part of a homeland for the Poles? Politically, it was thought unacceptable at the time, but it is part of Poland today, as is Western Galicia.

Another key aspect of WWI is that it was indeed a world war, not just on the Western Front. It was in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, Asia Minor, the Balkans, and Africa. In short, it was going to be very complex to unwind the military engagements all over the world – who would give up what territory and who would take it over? It was not just a matter of vacating Belgium and deciding what was to happen to Alsace and Lorraine.

It is worth mentioning the issue of the Ottoman Empire, which rather came into the war by the back door. The German High Command (OHL) believed that the Ottoman forces would equate to one percent of the German strength and would need bolstered. (Afflerbach points out the similar undervaluing of the Soviet army by the Allies in WWII, which ultimately pushed the Nazis and their allies out of the Soviet Union and all the way to Berlin.) In the end, the Ottoman army lasted until October 1918 and occupied 1.5 million Entente troops for four years, which was no mean achievement. The author points out the Ottoman view of Gallipoli, which was their first military success in 100 years or so, and which bolstered their morale enormously.

Looking at the strategy of the war, the author refers to two catastrophic political decisions which caused so much death and destruction. The first was not to avoid the war in the first place. He quotes Clausewitz’s dictum that war is the continuation of politics by other means, and indeed Foch said that one wages war only to get the desired result. The second catastrophic decision was to let the war run on so long, but it is much less discussed today. Lord Lansdowne aired this issue in 1917. The Entente are portrayed in other publications as wanting to prevent a German takeover of Europe, but was this a realistic fear? Afflerbach’s point is that the German system of government was deeply flawed, with a monarch as a central figure. The military leadership was a key political force that suffered from arrogance and tunnel vision, and a lack of reality. Germany’s allies, Austro-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria, were even more compromised, with moribund structures, certainly in the case of the first two. However, the Entente increasingly had imperialistic goals as the war progressed, and was less and less looking for an end to the war.

Professor Afflerbach opines that the two strategic mistakes which the German regime made were, firstly, the invasion of Belgium and, secondly, the U-boat war. The invasion of Belgium made it virtually certain that Britain would enter the war on the side of the French. The U-boat war of 1917/18 brought in the Americans as participants when perhaps otherwise they might have remained behind the scenes, possibly pressuring all sides for a political settlement.

So, the old order was destroyed by autumn 1918 and the new order did not function. But it could have been otherwise – it was all on a knife edge. In many ways, the problem for Germany and her allies was how to get out of the mess that they had created in 1914, and indeed they did try to do so, with an absence of success. They were in defensive positions on the Western Front and knew they could not win, especially once the US bolstered France and Britain with finance and supplies, and eventually with soldiers. The various voices in the German regime could not come up with a common position to solve the deadlock, in terms of what to concede, at various stages. As we have seen, the Entente were pushing their own war aims and perhaps would not have agreed to any negotiated settlement, earlier than they did.

Professor Afflerbach’s analysis of the situation is as follows:

The international club of war prolongers lived under a chimera, a concept of “victory”, which they expected to be the solution to the political problems, many of which emerged because of the war, and those existing ones that were aggravated because of it. This is not only an element of WWI but of wars in general and also can be seen in many conflicts of our own time.

The way out of the WWI conflict was open for a long time. It was such a bitter conflict with such wide-reaching consequences for various reasons. For a long time, it was perched “on a knife edge”; it lasted too long; it could have had other endings and both the victors and losers knew that; and the victors ultimately, weakened as they were, in their moral, social and financial misery which the war had generated, could not be other than merciless.