- Details

- Category: Dragon's Voice

The Dragon's Voice

The Newsletter Of The North Wales Branch Of The Western Front Association

June 2025

Next Meeting: Saturday 7th June

Open Meeting

Doors open 1.30pm for a 2pm start

A message from your chairman

Welcome to the June edition of “The Dragon's Voice”. Hope you are all keeping well. We have a quality selection of members giving a variety of talks at our open meeting. Thanks to John Storey for the minutes of the May meeting & for giving us all a “heads up” for our August away day. We have a few suggestions & I will put them to the vote at the next meeting. The “Wheeltappers & Shunters” Bell will make it's now customary appearance. If you didn't get to see it at the last meeting you are in for a treat! Again thanks to Phillip Baxter & his woodworker mate for the bell. Hope to see you on the 7th.

If anyone would like to contribute to the newsletter then please get in touch. It could be an article, a photo, an event local to you or something you think would be of interest to other members. Just email them to:

This newsletter will also be posted on the website: nwwfa.org.uk.

Please support the website by visiting it. If you have any information or articles for the website then please email them to me & I will add them.

Regards,

Darryl

Lest We Forget

An Unfortunate Death

By Darryl Porrino

John Robert Sedgwick

Private 2723 & 240755 5th East Lancashire Regiment

Date of death: 25/7/1917

John was born in Padiham, Lancashire in July 1888. He lived with his father John, a cotton weaver, and his mother Nancy Hannah at 5 New Street, Padiham. He had 3 brothers, William, Elisha & Ernest, and 2 sisters, Elizabeth & Rosetta. By 1901 they were living at 14 Kay Street, Padiham. He was a weaver.

John married Mary Elizabeth Ward on the 11th March 1915 and they lived at 81 Shakespeare Street, Padiham. He enlisted in Padiham on the 6th October 1914, into the 5th Battalion East Lancashire Regiment. He died on the 25th July 1917, following an accident whilst serving in Egypt.

The circumstances of his death:

Whilst on duty, and whilst sitting on the edge of a railway truck laden with railway locomotive rails, the train ran into a convoy of camels which were being driven by a private. Sedgwick was knocked off the truck and was pinned by the rails, which fell onto him, and rendered him unconscious. He was taken to a dressing station. On the 8th December 1916 he was admitted to the 27th General Hospital at Abbassia, where he was operated on. He was transferred to the 2nd Western General Hospital, Whitworth Street, Manchester, on the 16th July 1917. He was transferred to Didsbury Lodge on the 30th April 1917. He had suffered a fractured spine which resulted in paraplegia. He was discharged on the 14th July 1917 as no longer physically fit for active service. He died of his injuries on the 25th July 1917.

He is buried in Padiham Cemetery, Burnley, the same cemetery that my dad is buried in.

Rhyl's Involvement In The Great War

Here is a selection of newspaper reports of activity in Rhyl during the war.

Flintshire Observer 8/10/1914

Rhyl & The War

In addition to having been selected as the training ground for the North Wales Comrades Battalion of Kitchener’s Army, Rhyl also possesses convalescent homes & hospitals for wounded soldiers & a home for Belgian refugees.

Batches of recruits are arriving in the town daily & they are compactly billeted on the lodging house keepers at the west end, while they turn out on the prom for drilling. Their instructor is Sgt Major F.C. Ruscoe, an ex colour sergeant instructor of Volunteers & old army man, who was the 1st to be enrolled in the new battalion. Colonel Dunn is the commanding officer & Major Wynne Eyton, the adjutant of the Battalion.

Flintshire Observer 15/10/1914

Evidence Of German Brutality

Amongst the latest arrivals in Rhyl of the Belgian refugees are several men who have scarcely any flesh left on their wrists. They were dragged by ropes behind carts & horses by the Germans until they dropped from exhaustion, the ropes cutting into the flesh of the wrists. In another instance a father saw his 3 children killed before his eyes. An old lady made the journey to Rhyl wearing bedroom slippers.

Flintshire Observer 19/11/1914

The Troops At Rhyl

It was announced at Rhyl on Monday that the North Wales “Pals” Battalion would leave that town on Wednesday to join the North West Brigade at Llandudno & that their place in Rhyl will be taken by South Wales recruits.

It is expected that the Swansea & Llanelly Battalions will arrive during the weekend. The Entertainments Committee of Rhyl Council are arranging a welcome evening for the newcomers. On Monday the Town Hall was opened as a YMCA tent for the use of the troops in the town, the town council having decided to allow the YMCA the use of the hall with the exception of about twice a month.

The Brecon County Times 3/12/1914

The Welsh Army Corps

Something like 8,000 men have already been enrolled in the Welsh Army Corps & are at present in training either at Rhyl, Colwyn Bay , Llandudno or Portmadoc. Three battalions are up to their full strength viz the 1st & 2nd Rhondda Battalions at Rhyl under the command of Colonel Holloway & Sir William Watts C.B. respectively, & 1 of the Battalions of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers which includes ex public school men from various parts of the Principality.

Charles Herbert Morris

Lieutenant Royal Flying Corps

59 Squadron

Date of death: 13/4/1917

Age: 27

Charles was born in Buttington, Montgomeryshire in 1889. He lived with his father William, a draper, & his mother Jane at Severn Valley, Welshpool. His sister Mrs F Gamlin lived in Rhyl. He enlisted initially into the Royal Welsh Fusiliers & was commissioned into 59 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps as a lieutenant.

He was killed in action on the 13th April 1917. On that day he was part of 59 Squadron, based at La Bellevue, 8 miles north-east of Doullens. Six crews, flying RE8’s the RFC’s new plane, took off on a photo recon of Etaing, east of arras. Charles was the observer/gunner of A3216. His pilot, who was also killed, was Captain G.B. Hodgson. One plane, A3203, carried a camera & the other 5 were escorts. They were supposed to meet up with 2 flights from 19 & 57 Squadrons, but they failed to turn up.

They took off between 8.10 & 8.15am. It was twenty miles to Etaing, but they were north of their objective when they were shot down, so they either drifted off course or were chased before the dogfight. A3759, Pilot Lt M Wood & Captain J Stuart, was shot down by Manfred Von Richtofen, the Red Baron. The others were all shot down by Jasta 11, Richtofen’s squadron. Lothar Von Richtofen, Manfred’s brother, shot down 2. Wolff, Festner & Klein shot down the others. It was actually Lothar Von Richtofen who shot down Charles near Biaches-St Vaast. It was his 4th victory. He is commemorated on the Arras Flying Services Memorial.

A Training Excercise Goes Terribly Wrong. The Tragedy At Gainsborough 19th February 1915

By Malcolm Johnson

At the turn of the last century the Heavy Woollen area of the West Riding of Yorkshire, centred around Dewsbury, was a hive of industrial activity, specialising in the production of heavyweight cloth. One of the main activities in the town was the production of Shoddy and Mungo - this involved the recycling of wool from rags. In 1860, the adjoining town of Batley produced nearly two million pounds of shoddy.

Dewsbury had strong links with the local territorial battalion - the 4th King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Two of the battalion's eight companies were based in the town and had their drill hall in Bath Street.

The 4th KOYLI's catchment area was Wakefield ('A' and 'B' Companies), Normanton ('C'), Ossett ('D'), Dewsbury ('E' and 'F'), Batley ('G') and Morley ('H' Company).

This article relates a disaster that was to affect this battalion before they even set foot outside England.

On Saturday, 2 August 1914, the 4th KOYLI set off, with other local territorial battalions, to their annual camp; it was to be held at Whitby. Many of the men worked long hours, earning poor rates of pay in the local mills, and would therefore have had little opportunity of going to the coast; the annual camp was therefore seen by many as the highlight of the year. The following day, as it became clearer that there was going to be a war with Germany, naval activity could be seen out at sea (the Royal Navy had mobilised already). On Monday, 4 August orders were received for the battalion to return to Wakefield in order to be mobilised.

After returning to Wakefield (which proved more difficult than anticipated due to the rushed arrangements and the fact that the country was in turmoil), the battalion moved to Doncaster. In September the battalion was on the move again, this time to Sandbeck Park, east of Rotherham - the seat of the 10th Earl of Scarborough.[1]In November the battalion again moved, this time to Gainsborough in Lincolnshire, where it was to undertake coastal defence duties, in case the Germans tried to invade. It was whilst the battalion was stationed at Gainsborough that a tragic accident occurred on Friday, 19 February 1915.

At Morton near Gainsborough there were four gymes or deep pools (described by George Eliot in the book 'The Mill on the Floss'). These pools adjoined the embankment of the River Trent. As part of an exercise to gain experience in bridge building it was decided it would be worthwhile to practice the construction of rafts; 'D' Company, under Captain Hirst, was selected to undertake this exercise.

Harold Hirst

Harold Hirst was the 24 year old son of Joseph Hirst, a director of the family firm GH Hirst & Co Ltd. The firm was expanding, and was in the process of building a new factory, which was to be completed in 1916..

Harold, who had been a territorial officer since 1911, took 'D' Company to one of the gymes and started to make a raft (instructions of how this should be done being contained in a manual).[2] Two waterproof tarpaulin sheets were filled with straw and hay, they were each folded over and sealed with rope: these were the two floats for the raft. Planks were then placed on top as a platform. Captain Hirst boarded the raft and instructed a number of men to follow him. According to Captain Hirst's later testimony, the number of men that he allowed on board was between sixteen and twenty. A Lance Corporal who had some sea faring experience was given charge of the punting pole, and at about 12 noon the craft was pushed off from the bank. The raft drifted away from the banking and after about five minutes, being confident that it worked satisfactorily, Captain Hirst ordered that they should be punted back.

Unfortunately, despite being only a little way from the banking (possibly as little as the raft's length away) the punting pole would not touch the bottom - the pole being twelve to fourteen feet long. At this point the raft tilted slightly to one side; despite Captain Hirst shouting to the men to stand still, there was a movement to the other side of the raft. This sudden movement caused the raft to tilt in the other direction, in the words of one of the men "shooting everyone into the water".

Pandemonium broke out; although the men did not have packs on, their boots were heavy and they were out of their depth, a number of non-swimmers panicked and dragged other men under. Some men managed to scramble back onto the raft, others swam to the bank. Captain Hirst, despite being possibly the most heavily burdened man, made it to the shore where he gave orders for someone to go to the nearby village of Morton to summon help. By this time the activity had subsided, and he ordered a roll call to be held. To his horror he discovered that seven men were missing; at this point the battalion's Commanding Officer Lieutenant-Colonel Haslegrave arrived, and ordered Captain Hirst to return to Morton to change. The water was dragged and eventually the bodies of the seven missing men were recovered.

The inquest into the deaths was heard the following afternoon. Captain Hirst was questioned at length. During the hearing there was some contradictory evidence over the number of men who boarded the raft, it was suggested that it may have been as many as twenty-five. It was explained that the army handbook Captain Hirst was using did not specify the capacity of the raft and it was also suggested that the raft was in fact much further from the shore than Captain Hirst thought. All the men were inexperienced at bridge building, and the coroner reminded the jury that Captain Hirst had been carrying out the instructions of his superior officer. It was the first time he and his men had been engaged in doing such work and had never seen it done before.

The coroner said the gyme was a well-known danger spot and it was a terrible tragedy that they had gone there to carry out the exercise. Whether the men could swim or not, it seemed to him an extraordinary thing that work like this should be attempted in such a dangerous place. He added:

"However, I cannot see the officer in charge of this body of men (Captain Hirst) can in any way whatever be held culpable for what happened. It was his duty to carry out his instructions, and I have no doubt his superior officers were only doing what they had been instructed to do and what had been done by other comrades frequently."

The jury returned a verdict of accidental death on all seven men, adding a rider that it was very regrettable Captain Hirst and his men had been inexperienced and they considered the raft to be inadequate to carry such a large number of men. They also considered the life-saving equipment (one lifebelt) to be inadequate but fully appreciated the duties of the military were dangerous and hazardous, even in training, and recognised the difficulties of those in charge.

Colonel Haselgrave, the commanding officer, told the jury he felt the loss of these young men a great deal more than they could think.

The coroner said the young men may not have died on the battlefield, but they had died the death of soldiers, in the service of their country.

With the exception of Alfred Bruce from Harrogate, all the men who were drowned plus Captain Harold Hirst lived within a four mile radius. The seven men who died were:

- William Atheron (20) son of the late Harry & Elizabeth Atheron of Stanley Road, Wakefield. Buried in Wakefield Cemetery. Regimental number 2434;

- Edmund Battye (22) son of John Battye of Ward's Hill, Batley. Buried in Batley Cemetery. Regimental number 2067;

- Alfred Bruce (21) of Chatsworth Place, Harrogate. Buried in Harrogate Cemetery. Regimental number 2438;

- Ernest Cockell (20) son of Mr & Mrs George Cockell of 10 Stratheden Road, Wakefield. Buried in Wakefield Cemetery. Regimental number 2479;

- Frederick Cooke (34) Cardigan Terrace, East Ardsley. Buried at East Ardsley Parish Church. Regimental number 2425;

- William Dent (21) South View, Churwell. Buried in Morley Cemetery. Regimental number 1637;

- John Myers, (aged 24) son of William & Florence Myers of 14 Savile Grove, Savile Town, Dewsbury. Buried in Dewsbury Cemetery. Regimental number 1683.

News of the incident made the regional as well as local newspapers, the Yorkshire Evening Post reported the accident the following day:

YORKSHIRE SOLDIERS IN PONTOON ACCIDENT

FORTY MEN CROWDED ON LIGHT RAFT

LEEDS SOLICITOR'S SHARE IN BRAVE RESCUES

No official explanation has been given of the disaster to a pontoon-building party of the 4th Battalion of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (Territorials) at Gainsborough, by which, as was reported in the later editions of "The Yorkshire Evening Post" last night, seven men lost their lives, but from stories of the men engaged in the work it seems as if it were due to the pontoon being badly overcrowded by the forty or more men who were crowded upon it...

...Foremost amongst the rescuers was Lance Corporal Arthur Reginald Chorley,[3] a Leeds solicitor, partner in the well-known firm of Barr, Nelson and Co., of 4 South Parade. Mr Chorley, being anxious, like other Leeds gentlemen, to have a hand in the defence of his country, enlisted as a private in September and was given his stripe at the New Year. He it was who was responsible for saving the lives of Private Creighton, a Batley lad. He plunged into the water, and managed to get Creighton, who was then sinking, to the side.

Sergeant Charles Hemingway, of Dewsbury, one of the youngest sergeants in the battalion, also rendered notable service in the work of rescue, after having the greatest possible difficulty himself to struggle ashore. Despite the accident, the battalion's training continued, and on the 12th April 1915, goodbyes were said as the men were despatched to France as part of the West Riding Division.[4] Within a week the battalion had moved up to the front line and was being introduced to trench warfare in the Bois-Grenier sector.

May 2025

Next Meeting: Saturday 10th May

Where's Willie

Speaker: John Storey

Doors open 1.30pm for a 2pm start

A message from your chairman

Welcome to the May edition of “The Dragon's Voice”. Hope you are all keeping well. Thanks to Bridget & Phill for their articles for this edition. I have also incorporated a write up of Andy Moody's talk form April. Hope to see you on the 10th.

If anyone would like to contribute to the newsletter then please get in touch. It could be an article, a photo, an event local to you or something you think would be of interest to other members. Just email them to:

This newsletter will also be posted on the website: nwwfa.org.uk.

Please support the website by visiting it. If you have any information or articles for the website then please email them to me & I will add them.

Regards,

Darryl

Lest We Forget

Evan Rowland Williams

By Phillip Baxter

Last year I was fortunate to be able to visit Gallipoli. This was an adventure in itself, but whilst there I was able to commemorate a man who I’d vicariously come to know of through friends.

My friends Ian And Carolin lived at Tan yr Allt Isaf, Mochdre, which is a grade II listed 18th Century farmhouse tucked away from view by more modern properties: in a direct line, it’s less than 200m from my house.

However, at the time of The Great War the farm was the home of Thomas & Elizabeth Williams. Their son, Evan Rowland, had been born in Conwy in 1895 but lived with them at the farm. He worked for Mr. Clegg at his farm on Bryn Euryn (The large hill that dominates Rhos on Sea).

Evan enlisted in 1/5th Bn, Royal Welsh Fusiliers in Colwyn Bay serving in G Company as Pvt. 2162 E.R. Williams.

On the outbreak of war, on Aug 4th, 1914, his battalion mobilised, and training followed at Conwy, Northampton, Cambridge and finally Bedford prior to embarkation from Devonport on 19th July 1915; their destination was the island of Imbros.

On 9th August 1915 they crossed the sea to land at Suvla Bay as part of 158th Bde, 53rd (Welsh) Division. The battalion landed at 'C' Beach at 06.00 and bivouacked at Lala Baba, apart from ‘A’ Company, which was detailed to carry equipment up to the front line.

158th Brigade supported 159th (Cheshire) Brigade in an attack towards Scimitar Hill on 10 August and 1/5th RWF, as the brigade's leading battalion, moved forward at 04.45. The officers had no maps and confusion reigned, but the battalion advanced across the Salt Lake under heavy shrapnel and rifle fire, passing through the retreating battalions of 159th Bde at 11.30.

'Gallantly led' by Lt-Col Phillips, the battalion penetrated to within a few hundred yards of Scimitar Hill before getting broken up into small parties in the scrub. They took cover and opened fire on the Turkish front line at a range of 200 yards (180 m). Phillips sent back a message urging the 1/6th RWF to come up and help complete the job, but he was killed soon afterwards. The battalion was later withdrawn to 160th (South Wales) Bde's line; further attempts to take Scimitar Hill during the afternoon all failed. The battalion's casualties were 6 officers, and 13 other ranks (ORs) killed, 6 officers and 116 ORs wounded, and 39 missing, though many reported missing straggled back later

By October the 1/5th Bn's strength had been reduced to 18 officers and 355 ORs and it was temporarily amalgamated with the 1/6th Bn.

On 29th November 1915, whilst in the line, Evan was shot, and killed, by a sniper; he was 20 years of age, a farm boy from north Wales.

It took 8 weeks for his parents to receive notification of his death. After the war his name was included in the memorial to the village war dear at Nazareth Chapel, Mochdre. The Chapel is now in use as a commercial unit and the memorial rests in the village hall where it can still be viewed.

Evan has no known grave and is commemorated on the Helles Memorial.

I was able to commemorate Evan ‘in person’ during my trip to the peninsular last year. It was quite a poignant feeling being at the memorial. We were linked so closely by geographic residence yet separated by 100 years in time. I have no way of really knowing but my suspicion is that I was the first person to visit Gallipoli to remember him directly. With a sense of warmth, I left a small cross by the panel with his name on it, and I buried a small stone I’d brought from home in the soil beneath the panel.

Lost in battle, but remembered in name; lest we forget indeed?

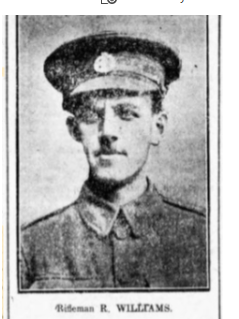

Rifleman Robert Williams S/4050 – Rifle Brigade, 13th Bn.

Son of Thomas & Kate Williams, Ship & Castle Hotel, Caernarfon

By Bridget Geogehan

Robert’s birth was registered in Carnarvon in 1889. From the 1911 Census we learn that the family lived at ‘The Ship & Castle Hotel, Carnarvon’ which had 15 rooms. His father was Thomas Williams, age 56, a Licensed Victualler & Tobacconist. His mother was Catherine Williams, age 44, she had given birth to 6 children of whom 5 were still living. Four of the children were in the house on this day; Robert was 21, single and a Clerk in ‘Gov. Labour Exchange’; his younger brother ‘William G.’ was 18 and a Draper’s Apprentice; his youngest brother ‘Richard P.’ was 7 and at school. Their sister, ‘Ellen M.’ was 14 and had no occupation. The family had a Domestic Servant, Catherine Griffith, who was 25, born in Llanwnda. Everyone spoke ‘Both’ - Welsh and English. All in the family had been born in Carnarvon except Catherine their mother who came from Llanrug.

The previous census, 1901 showed the family at 9 & 11 Bangor Street, Llanbeblig. Thomas, age 47 was a ‘Tobacconist & Tavern Keeper’, Catherine M was age 34. Robert was 11, Thomas J. 9, William G. 7 and Ellen M. 5. Richard P. Williams, a brother aged 34 was also staying in the house – he was a Chemist and Alice Thomas, age 16 was a Domestic Servant. Their next door neighbours were a Bank Manager and a Boot Dealer (Shopkeeper).

Of Robert’s life before the Army there is little evidence as yet. He was a civil servant, working firstly in the local Labour Exchange from where he moved to Head Office in Cardiff. He volunteered for the Army, Rifle Corps because he was a good shot. Farm boys were often chosen for ‘snipers’ because of their skill at shooting rabbits on the farm. From The Long, Long Trail 13th (Service) Battalion - formed at Winchester on 7 October 1914 but only came together over the next two days after moving to Halton Park. Came under orders of 63rd Brigade of 21st Division. 14 November 1914: moved to billets in Amersham and Great Missenden. Moved to Windmill Hill (Salisbury Plain) in April 1915 and transferred to 111th Brigade in 37th Division. 31 July 1915 landed at Boulogne.

However, this young man’s war ended when he had appendicitis. It was treated in a Military Hospital in France before the decision was taken to send him back to UK. He was one of the casualties on board the Hospital Ship ANGLIA which was mined and sunk. By coincidence, Tom Parry another Caernarfon lad was a crew member of the ANGLIA. She had been a passenger ship, sailing between Holyhead and Dublin before the war. The ANGLIA had only recently been refitted as a Hospital Ship and in early November had the honour of carrying King George V home. He had been out to the front, borrowed a horse and was thrown from the horse which caused him much pain.

Y Genedl of 30.11.1915: AR GOLL - Derbyniodd Capten T. Williams, Gwesty’r Ship & Castle, Caernarfon, y newydd trist o'r Swyddfa Ryfel, ddydd Mercher fod ei fab, Private Robert Williams, aelod o'r 13th Rifle Brigade, ar goll. Credir ei fod ar fwrdd yr "Anglia" a suddwvd yn y Sianel, Tachwedd 17eg. Yr oedd ef vn dod trosodd o Ffrainc lle y bu mewn ysbyty. Yr oedd Williams yn adnabyddus iawn yn y dref, wedi ei addysgu yn yr Ysgol Sir a bu yn y gwasanaothu yn y Gyfnewidfa Lafur am beth amser a thrachefn yn y Brif Swyddfa yng Nghaerdydd. 'Y mae gan Capten Williams ddau fab arall yn gwasanaethu eu gwlad. Tom a (ends here, mid sentence).

In Yr Herald Cymraeg of 30.11.1915: Ddydd Mercher, cafodd Capt. Williams, Ship and Castle Hotel, Caernarfon, hysbysiad swyddogol fod ei fab, Rifleman R. Williams, ymysg y personau anffortunus gollwyd oddiar fwrdd yr Anglia, y llong ysbytol suddwyd yn y Sianel yr wythnos ddiweddaf. Yr oedd Rifleman Williams vn 25 mlwydd oed, a pherthynai i'r 13th Rifle Brigade. Yr oedd wedi bod yn y gwarchffosydd yn Ffrainc er's mis Mehefin. Yn ddiweddar dioddefai oddiwrth appendicitis, a bu o dan driniaeth lawfeddygol. Wedi bod yn yr ysbyty yn Ffrainc am beth amser aethpwyd ag ef ar fwrdd yr Anglia er dod i'r wlad hon i wella. Cyn ymuno a'r fyddin gwasanaethai Rifleman Williams, yn y Gyfnewidfa Lafur yng Nghaernarfon. Yr oedd yn ddyn ieuanc dymunol a hoff us, a phawb a gair da iddo. Cydymdeimlir vn fawr a'i rieni ynghyda'r gweddill o'r teulu yn eu galar. / Gwr arall o Gaernarfon gollodd ei fwyd ar yr Anglia oedd Tom Parry, mab Pilot T. Parry, 41 Crown Street.

Memorials

Caernarfon Cenotaph: Robert Williams

Carnarvon County School (Ysgol Syr Hugh Owen): Williams Robert

Welsh National Book of Remembrance, page 927: The Rifle Brigade – Thirteenth Battalion – Rfn. Robert Williams Carnarvon

Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Rifleman Robert Williams – Service No: S/4050 – Rifle Brigade, 13th Bn. - Died 17 November 1915, Age 26 years – Commemorated at Hollybrook Memorial, Southampton – Son of Thomas and Kate Williams, of the Ship and Castle Hotel, Caernarvon.

Grave Records: Williams, Rfn, Robert, S/4050. 13th Bn. The Rifle Brigade. Drowned at sea (from H.S. “Anglia”) 17th Nov., 1915. Age 26. Son of Thomas and Kate Williams, of the Ship and Castle Hotel, Caernarvon. (H.S. - Hospital Ship)

There is a memorial to the Kings’ Royal Rifle Corps in the Cathedral Close, Winchester

THE KING’S ROYAL RIFLE CORPS

From the National Army Museum: In 1754, war broke out in North America over territorial disputes between British and French colonists. Both sides raised their own troops and were supported by military units from their parent nations and allies. At first, the British struggled to adapt to the irregular style of fighting they encountered. By 1756, they had formed a new regiment to help address this raised from settlers in the colonies of Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania, it was called the 62nd Regiment.

Men were recruited from other European countries, as well as British volunteers from other regiments. Its soldiers could move quickly and were trained to use natural cover. Its soldiers wore black leather helmets and green uniforms with scarlet facings, an early attempt at camouflage learned from experience of irregular warfare in North America. This battalion was the very first unit in the British Army to be equipped with Baker rifles.

It became known as The King's Royal Rifle Corps in 1881.

On the outbreak of the First World War (1914-18), 1st and 2nd Battalions deployed directly to the Western Front, remaining there throughout the conflict; 3rd and 4th Battalions arrived on the Western Front in December 1914. The regiment also raised 18 New Army battalions, but no further Territorial battalions, during the conflict. Post war it amalgamated with 2 other regiments of the Green Jackets brigade to form The Royal Green Jackets.

Seaman Thomas Richard Parry – Mercantile Marine – “Anglia” – Died 17.11.1915

Late 1890 there was a birth registered in Bangor for Thomas Richard Parry. In the Census of 1901 the family lived at 2 James Court, Llanbeblig. Thomas Parry, head of the household was 43 years old and working as a General Labourer. Thomas had been born in Carnarvon, his wife Anne in Pentraeth on Anglesey, she was 42. Their children were Anne aged 15, ‘Thomas R.’ age 10 who had been born in Rhoscefnhir on Anglesey, Rose age 8 and August (a son) age 5.

By the time of the 1911 Census the family lived at 3 Bank Street in Caernarfon, a house of 2 rooms. Thomas the Head of the household was a Pilot for Trinity House, his wife’s first name was given as Ellen, Thomas R, now 20 years old was a Sailor, August a News Boy and there was a grandson in the house, ‘Thos Richard Parry’, 15 months.

On 01.12.1915, in Y Clorianydd we get an idea of the numbers of people involved in this sinking: Yr “Anglia.” - Cyhoeddwyd y manylion swyddogol gan y Swyddfa ryfel ynglyn a suddiad yr “Anglia:” - Swyddogion wedi bodd, 4; gweinyddes, 1; bu farw dau ar y llong; bu foddi 27 o glwyfedigion a 100 eraill – cyfanrif, 134.

In Y Llan on 31.12.1915: Deoniaeth Arfon. - Caernarfon. - . . . Yr ‘Anglia.’ - Ymhilth y rhai a gollasant eu bwydau yn yr Ysbytty-long uchod cedd Tom Parry, mab Mr. Tom Parry y ‘pilot.’ Yr oedd ef yn un o hogiau Ysgol Sul Eglwys St. Mair.

There is more about Private Robert Williams in Y Genedl of 07.12.1915: Pte. ROBERT WILLIAMS, Caernarfon. Darlun yw'r uchod o Pte. Robert Williams, mab hynaf Captain Williams, Ship and Castle, Caernarfon. Yr oedd yn mhlith y rhai a gollwyd ar yr “Anglia.” Yr oedd yn y 'firing line' yn Ffrainc er Mehefin, ac yn ddiweddar tarawyd ef yn wael gyda'r appendicitis. Yr oedd yn 23ain mlwydd oed. Gweithiodd am amser yn y Labour Exchange, yng Nghaernarfon, ac yn ddiwedd- ar yn yBrif Swyddfa. yng Nghaerdydd.

Memorials

War Memorial Plaque, church of St Mary, Caernarfon: Tom Parry, A. B. Hospital Ship “Anglia”

Caernarfon Cenotaph: Tom Parry

Holyhead: the loss of the Anglia is commemorated by one of the ship’s anchors outside the Holyhead Maritime Museum

Welsh National Book of Remembrance, page 1066: Seaman Thomas Parry, Carnarvon – Anglia

Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Seaman Thomas Richard Parry – Mercantile Marine –

“Anglia” (Dublin) – Died Wednesday 17.11.1915 – Age: 25 – Commemorated: Tower Hill Memorial, UK. Killed by mine 17th November 1915. Son of Thomas and Ellen Parry, of 40, Crown St., Carnarvon.

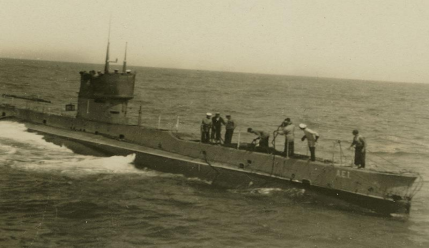

HMHS ANGLIA

The following is taken from Dover & Folkestone during the Great War (Pen&Sword 2008): The sinking of the Hospital Ship Anglia, 17 November 1915

Due to the ever increasing number of casualties from the Western Front, the initial complement of four hospital ships at Dover was supplemented with the arrival of a number of merchant passenger steamers, being Cambria, Anglia, Dieppe, Brighton and Newhaven. The fleet was marked in accordance with the Geneva Convention with the unmistakeable Red Cross flag. The Anglia, under her Irish skipper Captain Lionel Manning, and with most of her merchant crew from the Holyhead service, arrived after her refit in May 1915. She and her crew set about their new duties with enthusiasm and they must have been proud to have been given the delicate task, on 1 November 1915, of bringing the King back from France after he had sustained injuries when he fell from his horse whilst reviewing troops.

The morning of 17 November 1915 dawned clear and bright and a smooth crossing for the 386 casualties was expected. Casting off from Boulogne harbour at 11am, a little later than planned, Anglia headed for Dover taking the route reserved solely for the hospital ships, and which was marked by special buoys. As they approached the buoy just east of the Folkestone Gate, Captain Manning remarked to his men that they had made a beautiful crossing and went to fetch his gloves from his room. Just as he arrived back on the bridge, the ship was rocked by a massive explosion. Manning’s first thought was to call for help: ‘I at once jumped up and, going to the wireless cabin, ordered the wireless operator to send the SOS signal. I found his face cut and the room wrecked, and he explained to me that the apparatus was useless. I ran at once to the telegraphs to stop the ship, but found that they were broken by the explosion, and then hurrying to the voice tube I gave verbal orders to the engine room, but that was also broken. The ship was now very much by the head, and the starboard propeller was turning clear of the water.’ In these few sentences Captain Manning has described the ultimate nightmare for a stricken ship; no communication with the outside world, none with his engine room and the ship sinking bow first with her propellers still turning, thus driving herself under the waves. On top of this he had nearly 400 souls on board who could not fend for themselves.

For those who had managed to get into the boats, the welcome sight of the collier, MS Lusitania (not the cruise ship of the same name) hove into view. She had seen the explosion and turned round, lowering her own boats to help pick up survivors. Captain Manning described what happened next: ‘Our boats at this time approached Lusitania with a view to putting their crews on board. Being on the lower bridge at the time, I saw them proceed to Lusitania, but as the first man started to clamber on board the rescuing vessel there was another explosion, and the Lusitania sank stern first shortly afterwards.’

With their human cargoes aboard, HMS Ure and Hazard returned to Dover, and there began the tasks of counting the costs and discovering what had happened. Given the circumstances, it was perhaps miraculous that anyone had survived that cold November day, but the number lost was still considerable, and there was worldwide outrage. Of the crew of Anglia, 25 perished, consisting of the Purser, 4 deckhands, 12 engine room men and 8 stewards. There had been a total of twenty five medical staff on board, including 3 female nurses. Of these 10 orderlies and one nurse, Sister E A Walton, were lost. Of the 386 injured officers and men who had left Boulogne, and the battlefields of

France for what they expected was the safety of home, 5 officers and 128 men drowned.

Captain Lionel Manning was found floating, unconscious, in the sea and was rescued. A man of few words, Manning later praised the work of his crew and those of the rescue ships. He also told the story of one of the RAMC nurses, Sister M S Mitchell, who was found up to her waist in water in B Ward trying to bring out a cot case. Lieutenant Bennett who found her helped to bring the invalid up to safety, but he then had to use force to stop Sister Mitchell from returning to the ward, where she would certainly have perished.

The cause of the disaster was quickly established. The German mine laying submarine UC-5 had set a chain of mines around the buoy which, as already mentioned had been placed for the sole use of returning hospital ships. It might have been thought to have been a terrible mistake by the captain of UC-5 but a communiqué issued from Berlin the next day made it clear that it was not. It was claimed that the British were using vessels, masquerading as hospital ships, for carrying combatants and munitions, though no evidence to support this claim was ever produced, and it was strenuously denied by the Admiralty.

From Epsom & Ewell History Explorer:

Within a few hours (of the loss of the ANGLIA), survivors were placed on board hospital trains with many arriving in Epsom to be treated in the local War Hospitals. J.R. Lord, in his book The Story of the Horton – Co. of London – War Hospital: Epsom, describes the arrival of some of the survivors:

Survivors of the “Anglia” admitted. – The night of 17th November, 1915, will never be forgotten, for it was the occasion of the admission of 112 soldiers and two sailors, survivors of the hospital ship Anglia, which had been mined and sunk in the Channel. A cabin boy, from the collier Lusitania, was also admitted, his ship having been sunk while engaged in noble rescue work. The disaster took place about mid-day, and shortly after 8 p.m. I had the worst of the survivors safe in the wards.

All, more or less, were suffering severely from immersion in the sea, and many were severely wounded. Their condition on arrival was most pitiable. I had a huge pile of blankets waiting at the station, in which the patients were at once wrapped, and the journey to the hospital was made in record time. On arrival there every means were taken thoroughly to restore life, many being dazed and others partly or completely unconscious. They had gone through a terrible experience; some had been twice immersed, and had lost all they possessed; some even lost their pyjamas and were admitted quite naked but for blankets.

Two of them it was impossible to identify, one of whom died very soon without ever returning to consciousness or uttering a word. It was not until the day fixed for the funeral that, with the assistance of the War Office Casualty Department, and the ring the patient was wearing, I was able to surmise who he was. I postponed the funeral for a day, and sent for the relatives, who satisfactorily identified him just before he was buried.

The other “unknown” was suffering from a fractured skull, and in his delirium uttered words which belonged to no language we were acquainted with. I suspected paraphasia, but on the night of admission it was rumoured he was a German from his appearance and language, and some ugly threats were heard from other patients in the ward, who were highly incensed at the whole affair, especially as the survivors were convinced that the ship had been torpedoed. The story was that the

Anglia had been dodged (sic) by a strange foreign-looking vessel, which had done the dastardly deed, and that the “unknown” speaking the foreign language had fallen overboard and been rescued with those from the Anglia.

It was known there were no German prisoners on board the Anglia. However though the story was scarcely credible, I wished to avoid any trouble with the other patients, so I had the patient moved to a wing of “A” hospital, and put in safety under an armed guard from a neighbouring camp for a few days, and set about the work of identification. It took some days, and several missing soldiers’ relatives were sent for without success. At last, however, the right relatives were found and he was correctly identified. We had good ground for our mystification regarding his language, for he was a paraphasic Welshman trying to speak his native tongue. He never regained consciousness, in spite of every effort to repair his skull, and died on December 7th.

Message from the King. – On the morning following the arrival of the survivors of the Anglia, I received by telephone the following gracious message from H.M. the King, which I read to the patients congregated in the recreation hall and published in a special order :- “His Majesty the King desires that a special message of sympathy be conveyed to all Anglia patients, and has expressed the hope that they may quickly recover from their trying experience.”

HMHS ANGLIA & KING GEORGE V

From the Great War Forum, John Bourlon De Pree was the son of Major General Hugo Douglas De Pree, who was a nephew of Earl Haig. Another relative, Ruth De Pree wrote some memoires regarding Earl Haig (copyright Peter De Pree, so just one paragraph transcribed about the incident:: "He describes His Majesty's visit to the Front and his fall from the horse which my Uncle had lent him, and he said it had been trained to all sorts of strange sounds and noises, but the Flying Corps took off their helmets and waved them below the horse's nose. This made it rear up and fall backwards with His Majesty. "His temperature today is normal, and he returns home quite a hero".

This is the entry from the Matron-in-Chief's war diary [TNA WO95/3988]:

29.10.15 GHQ [St. Omer]

Left 9, arrived 11am St. Omer. Went to office. Saw DG who was on his way to Boulogne to make arrangements about Hospital Ship to convey H.M. Home Everyone anxious that he should be moved with as little delay as possible as soon as the move could be done with safety – a certain amount of anxiety existed in consequence of the fear of the Chateau being bombed, as soon as the Germans learnt what had happened.

DG instructed me to go to Chateau and see Sir Bertrand Dawson. Reported first to DMS 1st Army, where I was informed by Surgeon General Macpherson that the accident occurred at 11am, and that Miss E. Ward QAIMNSR who has previously nursed the King and who was fortunately on a Barge nearby was got at once. And the Canadian Sister in Charge of the Canadian C.C. Station be selected for night duty – thought it would be a good political move, and that she had been on duty and that the king liked her.

Had lunch at Mess, then went to station to make arrangements about 14 Ambulance Train, which was to be got ready. Arrangements and necessary arrangements were left to me. The treatment room was converted into a ward. Carpeted, a deal of Cretonne covering head [of] bed, flowers etc., procured. Orders given that he was leaving 11am tomorrow, only certain coaches for

suite, servants and personal attendants on the King were to be used, the remainder of train left behind. Pouring wet day – got back late. After dinner learnt removal postponed till Monday.

30.10.15

Pelting day. Went again to Chateau. Saw Miss E. Ward the Nurse. Everything going on satisfactorily, the King having a great deal of pain, suffering from severe bruising, fortunate no internal injuries and no bones broken. Hospital Ship Anglia to take H.M. over – patients will be on board also. . . . Dined at Mess, learnt again that H.M’s departure was again postponed until Monday, the King unwilling to go. Shawls, jacket required. With difficulty got shawls which I took, but which were not suitable.

30.10.15

Pelting day. Went again to Chateau. Saw Miss E. Ward the Nurse. Everything going on satisfactorily, the King having a great deal of pain, suffering from severe bruising, fortunate no internal injuries and no bones broken. Hospital Ship Anglia to take H.M. over – patients will be on board also. . . . Dined at Mess, learnt again that H.M’s departure was again postponed until Monday, the King unwilling to go. Shawls, jacket required. With difficulty got shawls which I took, but which were not suitable.

31.10.15

The King to leave 10.30am tomorrow. Message from DG to the effect I was to meet him at Aire Station 9.45am.

01.11.15

Left early with Miss Lyde for Aire, calling at Chateau and leaving shawl for the King. Then on to Station to 14 Train to see that all final arrangements were complete. Everything in order and looking first rate, except the weather, still very wet. Over head aeroplanes were guarding us. The Suite, servants and luggage began to arrive. Later Generals French, Haig and Sloggett. Then a little convoy of Ambulances, the King in one – the Nurses and Surgeons arrived. I assisted to lift him onto his bed. Before leaving the King decorated a L/c Coldstreams with V.C. Everyone most gracious. Sir A. Bowlby anxious for me to go to Boulogne in the train, however I decided to go by car so that I would be able to see that all arrangements on the Anglia were correct. Left by car after departure of train. Called at office. Drove to Boulogne to office, where I had lunch and then went with Surgeon General to Anglia. Found everything beautifully arranged. Waited till I saw the King safely and comfortably established in his bunk and then returned to Hotel to see Miss Kelly late QAMNS I who had come over from W.O. with 10 Special Probationers. Drove her with Miss Warrack and Indian Sister who had come to meet her to Rawal Pindi Hospital and then drove to Abbeville arriving 6pm. Saw DMS and told him all the news.

Musical Box By Andy Moody

Andy gave a talk about a Whippet tank “Musical Box” & the actions of the 3 crew members on the 8th August 1918 during the Battle of Amiens. Musical Box became the lead tank as others were knocked out. Lt Clem Arnold, of Llandudno, He ordered his crew to drive across the German lines of fire whilst engaging the German battery with machine gun fire. They caused considerable damage to the German artillery over a period of about 11 hours.

Inevitably they attracted machine gun fire, which punctured the spare fuel cans on the roof causing the petrol to leak into the cab. Two shells then hit the tank causing the petrol to ignite inside the tank.

Clem Arnold later recalled: “Petrol was running down the inside of the back door. Fumes & heat combined were very bad. I was shouting to driver Carney to turn about when the cab burst into flames. I managed to get the door open & drag the other 2 out. The fresh air revived us & we all got up & made a short rush to get away from the burning petrol. We were all on fire. We rolled over & over to try & extinguish the flames.”

On escaping the tank, Arnold & his crew were met by a group of German soldiers seeking revenge for the deaths of their comrades. Arnold's driver was shot & killed & he & his gunner were savagly attacked.

“I saw numbers of the enemy approaching from all around. The first arrival came for me with a rifle & bayonet. I got hold of this & the point of the bayonet entered my right forearm. The 2nd man struck at my head with the butt end of his rifle, hit my shoulder & head, & knocked me down. When I came to there were dozens all around me & anyone who could reach me did so & I was well kicked. “

A German officer, Ritter Ernst von Maravic, intervened to stop the attack & saved the lives of Arnold & his gunner, private Ribbans, both oh whom were taken prisoner. Arnold was awarded the DSO for his actions on that day.

Andy then went on to describe how he got invloved in the making of a replica of Musical Box, despite having little technical & mechanical experience.

The Replica Musical Box

April 2025

Next Meeting: Saturday 5th April

Musical Box. The Tank Corps At Amiens 1918

Speaker: Andy Moody MA

Doors open 1.30pm for a 2pm start

A message from your chairman

Welcome to the April edition of “The Dragon's Voice. Hope you are all keeping well. Nice to see our old friend The Bulletin has arrived! I'll go through the contents at the meeting. Andy Moody will be giving his talk that has a local connection to our branch. I won't say anymore, I'll leave it to him. Hope to see you all there. Thanks to Keith Walker for this month's book review.

If anyone would like to contribute to the newsletter then please get in touch. It could be an article, a photo, an event local to you or something you think would be of interest to other members. Just email them to:

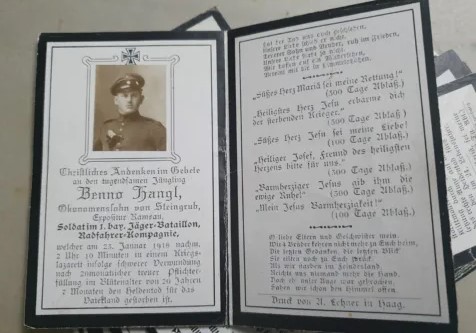

The Hangl Brothers

By Darryl Porrino

As some of you know, I have a collection of over 500 German DDWW1 memorial cards. Here is the story of a recent addition.

I recently bought a German Memorial Card (Sterbebild) remembering Benno Hangl. A bit of research revealed there were nine Hangl brothers, 8 served & four were killed in action. Here are their stories.

Benno was born in Steingrub, Wasserburg, Bavaria on the 13th June 1897. His parents were Josef, a farmer, & Hedwig. He had 7 brothers, Ignaz, Josef, Georg, Lorenz, Alois, Matthaus, Markus & Peter.

Benno enlisted on the 2nd June 1916, originally into the 3rd Einsatz Infantry Battalion. He was transferred to the 1st Bavarian Jager Battalion, Cyclists Company on the 12th October 1916. He died of wounds received in action on the 23rd January 1918 at a military hospital. Unusually the specific time of his death is recorded as 2.10pm. He is buried at Pordoi German War Cemetery, Italy. He was 20 years old.

His brother Lorenz was born in Steingrub on the 8th August 1886. He was an infanteriest in the 2nd Bavarian Landwehr Infantry Regiment, 7th Kompagnie. He died on the 8th March 1915 & is buried at the German War Cemetery, Souain, Marne.

Another brother Markus was born on the 16th April 1892. He enlisted into the 2nd Bavarian Infantry Regiment, 12th Kompagnie. He held the rank of unteroffizier (sergeant). He was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class & the Bavarian War Service Cross 3rd Class. He suffered shrapnel wounds on the 10th June 1917 & he died of his wounds on the following day. He is buried at Veslud German Military Cemetery.

The fourth Hangl brother to be killed was Peter. He was born on the 1st June 1896. He enlisted on the 20th October 1915 into the 2nd Ersatz Battalion, 16th Bavarian Infantry Regiment. On the 24th June 1916 he was transferred to the 20th Bavarian Infantry Regiment. He died of wounds received at Thiaumont, Verdun, on the 7th July 1916. The brothers are commemorated on the memorial on their local church, Maria Loreto at Ramsau.

If any of you would like to collect these type of cards I would be happy to give you a few pointers. They are readily available particularly on ebay. There are various websites to help you research the men.

Volksbund is the German equivalent of the CWGC. There is an English language version:

Together for peace - understanding and reconciliation | Volksbund.de

The Denkmal project also helps you to find where they are commemorated, and includes phots of any memorials that are relevant:

Online project Monuments to the Fallen

There is also an American published book: “When The Leaves Fell” by Marc Jay Johnson. It explains the terms used on the cards & what details to look for. It is hard to come by but I am willing to lend out my copy if anyone is interested.

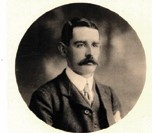

Harold Owen Bodvel-Roberts

By Darryl Porrino

2nd Lieutenant 7th London Regiment MC

Date of death: 18/11/15

Age: 35

Harold was born in Caernarfon in 1880. He lived with his father John Hugh, a Clerk of the peace, and his mother Gwen Bodvel Roberts at Cefn Y Coed. By 1901 he was living at 22 Kensington Court, Kensington, London where he was a bar student. He later became a solicitor.

He joined the 7th London Regiment in August 1914. He entered France in March 1915. He was awarded the Military Cross on the 25th September 1915 during the Battle Of Loos.

The citation reads;

For conspicuous gallantry at Loos on the 25th September 1915 when he led his men with great coolness and bravery against the German counter attack. He was wounded in both legs. He was the 1st 7th London Regiment officer to be decorated.

He died of wounds received in this action at the 3rd General Hospital, Le Treport, France. He is buried at Le Treport Military Cemetery, Seine Maritime, France. Plot 2, Row O, Grave 24.

REMEMBRANCE by

THERESA BRESLIN

Published by Doubleday 2002

My copy second hand Corgi paperback 2014 £7-99

Even though the book is call Remembrance.

I cannot remember how I came across this novel. The blurb on the back cover stated.

“ Brilliantly weaves the themes of emancipation, class, love propaganda and the machinations of war into a story of how these young lives are changed.”

Financial Times

“ Immensely readable, passionately written “.

Guardian

Most of my reading is non fiction, but I do like a good novel every now and then. This novel starts in the summer of 1915. The main characters are in their late teens early twenties.

The novel was a real gem. The prose is wonderful, I found myself stopping reading and going back to read a passage again, the writing was so good.

The author pulled no punches on the horrors of war or on the emotions of the central characters in the book. You cannot say you enjoyed a book about war. Enjoy is not a word you can use about war. But after reading and rereading some of the passages I remembered that quote “ you know when you have read a good book and finish it, you felt like you have lost a good friend.”

I really fell in love with the book,so much so, I searched the internet for a First Edition 2002 hardback copy to add to my library.

A powerful well written, thought provoking book . I highly recommend it.

Keith Walker

2025

February 2025

Next Meeting: Saturday 1st February

Le Cateau- Niall Cherry

Doors open 1.30pm for a 2pm start

A message from your chairman

Welcome to the February edition of “The Dragon's Voice”. Our next meeting is on Saturday 1st February when Niall Cherry returns with another of his excellent talks. Hope to see you all there. By now you should have received the branch mailshot which consists of an introductory letter about the branch & a list of our meetings for the coming year. Hopefully some of our members who do not attend the meetings might be tempted to turn up & “give us a go”. I have passed on the branch's thanks to Maya & Lisa at WFA HQ for their sterling efforts in getting this done for us. Our attendances are very good especially when other branches seem to be struggling so thanks to you all for your continued support.

If anyone would like to contribute to the newsletter then please get in touch. It could be an article, a photo, an event local to you or something you think would be of interest to other members. Just email them to:

This newsletter will also be posted on the website: nwwfa.org.uk.

Please support the website by visiting it.

Darryl

Lest We Forget

From Jill Stewart at The Western Front Association

Dear All,

We are delighted to announce an increased number of webinars for the first months of 2025. Whilst we have previously looked to undertake these fortnightly, we have aimed for a weekly schedule for the start of the New Year. Details of the WFA 'Monday evening webinar' schedule is below. Note: All these commence at 8pm UK time

Monday 3 February "The British Way in Warfare - Salonika, 1915-1918"

by Alan Wakefield

This talk examines the way in which the British Salonika Force (BSF) under Lt General Sir George Milne conducted operations in Greece and Serbia during the First World War. The focus is on the way in which local factors such as terrain, climate and the threat of disease combined with the BSF's internal weaknesses resulted in very different military experiences for British soldiers serving on the four main sectors of the British front in Macedonia.

The British Way in Warfare - Salonika, 1915-1918 Monday 10 February "Turning Points 1915"

by Dr Spencer Jones.

From the first use of poison gas at Ypres to the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign and the shifting dynamics on the Eastern Front, this lecture delves into the events that shaped the trajectory of the First World War. Learn more about the decisions, innovations, and missed opportunities that could have altered history, and consider how the course of the conflict - and the world - might have been dramatically different. This presentation, by Dr Spencer Jones follows on from the highly successful 'Turning Points 1914' which Spencer presented in 2024. We hope this will become a series that will develop for each year of the war. Turning Points 1915 As ever, please keep your eye on the WFA website in order book early and therefore get a good seat at our forthcoming events !!!

2nd Lt Guy Everingham 28/6/1894 - 8/4/1917

by Darryl Porrino

Guy was born in Barry, Glamorgan on the 28th June 1894. He was the son of William and Patricia Florence Everingham. He had a brother Robin. He was living at “Vaenor”, Hawarden Road, Colwyn Bay when war broke out. He enlisted in August into the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. He was spotted as officer material, and was gazetted as 2nd Lieutenant into the same battalion on the 25th February 1915. He entered France in March 1916. He served as a line officer, and later as a bombing officer in the 113th Trench Mortar Battery. He successfully applied to join the Royal Flying Corps in September 1916.

He married Gladys Annie Brown at Holy Trinity Church, Llandudno, on the 19th February 1917. They set up home at “Lynwood”, St David's Place, Llandudno. After a short period of leave he returned to France for duty with 16 Squadron. He was killed in action on the 8th April 1917. The authorities informed his mother but not his wife & she had to go to her and convey the sad news.

On the day he was killed he was an observer in a BE2, piloted by Lt Keith Ingleby MacKenzie. They were on observation duties over Vimy Ridge. They had taken off at 1500 hours and British ground observers witnessed their plane shot down at 1640, 1,000 yards west of Vimy. Due to them falling behind enemy lines they were not recovered for burial until a week later.

They were shot down by Manfred von Richtofen, the “Red Baron.” This was his 39th victory. He reported, “I was flying and surprised an English artillery flyer. After a very few shots the plane broke to pieces.”

His commanding officer wrote:

“We miss him dreadfully and find that he has left a gap which I can never hope to fill. He was always so full of life and keen on his work. In addition to his duties as an observer he was of great assistance to me elsewhere.”

He also wrote to his pilot Lt MacKenzie's parents:

He went out on the 8th April with Lt Everingham as observer, on photographic work, a duty which entails greater risk and requires more nerve than any other . They were attacked by a hostile scout, which was a much faster and more deadly than their machine and they were apparently were surprised. Their machine fell out of control just behind what was then the German line. I hear today that we are in possession of the ground which the machine is lying and I have sent out a party to obtain further particulars if they can be obtained.”

He later wrote:

“ His machine was picked up on the 15th by a party of my men near the Bois De Bonval on the Vimy Ridge. The pilot and observer were found lying together quite close by and were laid to rest on the eastern slopes of the ridge. I am glad to be able to say that neither of them can have had any suffering. Both were hit by machine gun fire and must have been unconcious before reaching the ground. I regret to say that they had been searched and their pockets emptied by the Germans before they were driven off. I hope that in due course these articles will reach you through the usual channels from the enemy.”

Guy is buried at Bois-Carre British Cemetery, Thelus, France.

The Liverpool Echo reported:

Lt Guy Everingham of the Royal Flying Corps has been reported as missing. He was a motor engineer by profession. In the early days of the war he enlisted in the 1st Battalion of the “North Wales Pals”, which became known as the 13th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers. With this now famous unit he saw considerable service before he joined the Royal Flying Corps. His mother, who lost her other son in the war, resides in Colwyn Bay. Lt Everingham was married in Llandudno two years ago. His brother Robin was a trooper in the Welsh Horse and was killed in action at Gallipoli on the 10th December 1915.

Guy is also commemorated at St Tudno's Churchyard, Great Orme, Llandudno.

Rhyl & District British Red Cross Hospital

The Hospital for Wounded Soldiers at Rhyl is 1 of 2 Red Cross Hospitals maintained in Flintshire under the auspices of the Flintshire Committee of the British Red Cross Society.

The Committee were fortunate in finding the Men’s Convalescent Home at Rhyl, which was kindly placed at their disposal by the trustees, a building admirably suited to their purpose. It opened on March 1st of this year, with 52 beds, & 33 patients arrived that day. It is affiliated to the 2nd Western General Hospital, Manchester, & the inspectors have, from time to time, all expressed their unqualified approval of the way in which the hospital is being carried on.

The healthful air of Rhyl, the skill & care of the doctors & nurses, & the kindness extended to the patients on all sides have combined to accelerate their convalescence. They have particularly appreciated the action of the Municipal Authorities in granting them free passes to the Marine Gardens & all their entertainments, & also the picture palaces etc, under private management, where they are accorded a similar privilege. Motor drives & coach drives have also been privately given & greatly enjoyed.

So successful in fact has the hospital been that at the request of the Military Authorities, another wing, with 24 additional beds, has been opened up at the end of August. 171 patients have been received, of whom 104 have been discharged & 67 are at present in the wards.

Book Review

The Mountain War, A Doctor’s Diary of the Italian Campaign 1914 – 1918

By Dr Isaak A Barash

Pen & Sword, 2021

£20.00, 220 pages, photographs and index

ISBN 978–1–39909–310–1

[This book review first appeared in the April 2022 issues of Stand To! No.126]

There are so few Austrian or Italian memoirs from the Italian Front translated into English that it’s refreshing to find this offering from Pen & Sword detailing the life of an Austro–Hungarian military doctor. I do feel, however, that the subtitle (A Doctor’s Diary of the Italian Campaign 1914 – 1918) is somewhat misleading, as war on the Italian Front didn’t start until May 1915, and Barasch’s diary begins with an entry for 22 January 1916.

Nevertheless, the diary offers us some fascinating glimpses into the last days of the Austro–Hungarian empire and an army riven with snobbery, class divisions and ethnic/religious/nationalistic tensions. The son of a Jewish tenant farmer from the furthest corner of the empire (eastern Galicia, in what is now Ukraine) Barasch would have had lowly status by Austro–Hungarian standards. Without his medical degree he would have ended up as a front line infantryman, but somehow Barasch made it to medical school in Vienna, and then as a medic to a Landsturm regiment when he was called up.

Barasch’s diary recounts his daily experiences as a doctor for the 106th Landsturm Division on the Isonzo, in the mountains of the Tyrol and finally on the Piave. Although technically a division of reservists, the 106th saw almost continuous action, both in Italy and on the Eastern Front, as well as a brief spell on the Western Front in late 1918.

Barasch doesn’t devote much space in his diaries to the actions his Division were engaged in, focussing more on the medical and administrative aspects of his experiences. And they were not happy experiences – he spends most of the diary writing about how tough and miserable his life was, complaining about the places he was posted, the local womenfolk, his lazy commanders and his uncomfortable bed.

To be honest, it’s hard to feel much sympathy for Barasch, especially if you’ve read some of the other memoirs from this front: Hans Pölzer describes in stomach–churning detail how he burrowed his way into a rotting corpse to escape Italian machine gun fire, Joseph Gál describes how his life–long friend died in his arms and Franz Arneitz describes how he spent 50 consecutive days on a mountain ledge under fire from Alpini above. Barasch’s slightly leaky hut several miles behind the front line, and the occasional missed meal, seem rather insignificant by comparison.

Barasch does give us an insight into the workings of the army medical corps, the sort of injuries they had to deal with and the problems associated with evacuating wounded men from mountaintop positions. He also shines a light on how Austria–Hungary was experiencing severe shortages as early as 1916, and he seems to spend more time hunting down medical supplies and building materials than tending to the wounded. That’s when he’s not off to Regimental HQ for a bath or writing to his CO requesting a transfer away from the front....

The diary also gives us an interesting glimpse into the religious tensions of the time. Barasch devotes quite a lot of space to his loathing of the Pope and the Catholic church, and he considered the Italians to be as treacherous and untrustworthy as their pontiff.

Although Barasch comes across as a snob and a moaner, that doesn’t take away from the interesting details of his life as an army medic. The sections by Sir Hew Strachan, who writes about the military situation on the Italian Front in a concise, intelligent way, help contextualise the diary and give the reader a good understanding of the war in Italy.

Review by Tom Isitt

January 2025

Next Meeting: Saturday 4th January

Doors open 1.30pm for a 2pm start

A message from your chairman

Welcome to the January edition of “The Dragon's Voice”. Happy New Year. I hope you all had a peaceful & enjoyable Christmas. Our 1st meeting of the year has our very own Steve Binks giving a talk about the 1st Day Of The Retreat & The Actions At Elouges 24th August 1914. With the disappointment of the cancellation of our Christmas Social, there will be a belated buffet of quiche, sausage rolls & mince pies. Hope to see you all there.

If anyone would like to contribute to the newsletter then please get in touch. It could be an article, a photo, an event local to you or something you think would be of interest to other members. Just email them to:

This newsletter will also be posted on the website: nwwfa.org.uk.

Please support the website by visiting it.

Darryl

Frederick Marshall Arnold

Lieutenant 5th Royal Welsh Fusiliers (attached 9th Btn)

(Flintshire Territorials)

Date of death: 27/3/1918

Age: 21

Frederick was born in Rhyl in 1897. He lived with his father Robert Balding Arnold, a draper, and his mother Mary Anne at Chester House, Queen Street, Rhyl. He had three sisters, Mary Annie, Emily Amelia and Elsie Gwen, and a brother Arnold. They later moved to 53 West Parade.

Frederick went to the University Of London & whilst there he joined the Officer Training Corps. He was gazetted as 2nd Lieutenant on the 7th January 1916 & then to Lieutenant with the 5th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

He entered France on the 5th February 1918. He was killed in action on the 27th March 1918, near Hebuterne, France.

According to the regimental records;

At about 10am, when practically the whole remnant of the 58th Brigade and other units were in Hebuterne, the enemy appeared in force on the south-eastern edge. The composite battalion withdrew to the north western outskirts taking up a defensive position until the situation could be more accurately gauged. The 57th Brigade was in touch on the left and the 56th in reserve, but there were no troops on the right. Fighting and reconnoitering patrols were pushed out and through Hebuterne, some of them actually led by Brigadiers of the 58th and 57th Brigades. The enemy had siezed various positions and houses, and his concealed machine guns proved very troublesome. There was street fighting with many casualties, but by dusk the village was cleared and some prisoners and a machine gun were taken. A line of outposts along the south and east of the village was then established and a continuous line of defence organized.

Our 9th Battalion casualties were returned as six officers killed ( Captain F M Arnold, Lt's Nash, Ellis, HF Owen, W Handley and ET Lllewellyn). Other casualties were lumped together under the figure 443.

He is buried at Faubourg D'Amiens Cemetery, Arras.

The Rhyl Journal reported: 13/4/1918

Lt Frederick Marshall Arnold, Royal Welsh Fusiliers, son of Mr & Mrs R B Arnold, Chester House, is reported to have been badly wounded on the 25th March. Further news concerning him is anxiously awaited by his parents. He is one of three soldier brothers, the other two being in Palestine. He has been in France for 6 months.

It happened in the barber’s where my mother had taken me when I was a young child.

By Peter Crook WFA 2018

‘Mummy, why is that man making funny noises?’

The wheezing, rattling and muted bubbling sound stopped briefly as he turned to look at me, expressionless, then nodded towards my mother and turned away.

My mother gave a very, very sharp tug on my coat sleeve. ‘Shhh! You’re being rude. I’ll tell you when we get outside.’

And so she explained. The man had been gassed during the First World War. ‘You know what a war is, don’t you’ said my mother. Actually, I did, my father having just returned from one. My mother went on: ‘He was in the local Regiment, the Welsh Regiment, I think. Do you know what a Regiment is?’ Actually, I did, my father having been in one and having told me what it meant.’

I don’t think I saw that poor suffering man again.

But I suppose it might have been at that moment in the barber’s – or perhaps more precisely just afterwards when my mother did her best to satisfy my childish curiosity – that my interest in the First World War began.

And, every now and then, even after I had left Wales, my interest focused on the Welsh soldiers in that war. How had that man become a soldier? Why had he joined the Welsh Regiment? (Wasn’t it the ‘Welch’ Regiment anyway? That’s what the soldiers who lived in the nearby Maindy Barracks had on their cap and shoulder badges.)

I came to wonder, in the course of time and learning, why the 38th (Welsh) Division in the First World War, that so many men in the Welsh Regiment belonged to (in fact, including the Pioneer Battalion, there were seven Welsh Regiment battalions in this Division at its formation), did not seem to have been ‘famous’ or regarded as having a great ‘fighting reputation’ despite its impressive record in battle between 1916 to 1918. And its record in battle was, indeed, impressive.

In 1916 in the Battle of the Somme the Division captured the largest wooded area in the battlefield, Mametz Wood, in five days, whereas it took other units months to capture the much smaller High and Delville Woods. In 1917 on the opening day of the Third battle of Ypres, while others floundered, the Division rapidly advanced three kilometres and achieved all its objectives. In 1918 at the start of the British counter-attack and final advance the Division advanced 15 miles in 15 days setting the pace that the British army maintained until the Armistice.

Perhaps the reason for the paucity of official praise for the Division’s achievements (until 1919) is its association with David Lloyd George, the Welsh Liberal politician and Prime Minister from December 1916. It is safe assumption that few Generals in the British Army were Liberals. It is also a safe assumption that many, perhaps most, regarded him as an untrustworthy parvenu Welsh ‘outsider’, dangerously ignorant of military matters. It is true that the 38th (Welsh) Division did not get off to an easy start.

The creation of 38th (Welsh) Division

The creation of the Division began with a speech made by David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, on 19 September 1914 at a meeting of London Welshmen at the Queen’s Hall in which he had appealed for the formation of ‘a Welsh army in the field’. Subsequently, in order to give this idea substance, the Welsh National Executive Committee was formed in Cardiff on 29 September to organise the recruitment of ‘a Welsh Army Corps’ of two or more divisions.

Every effort was made by the WNEC to create a totally Welsh formation. The use of the Welsh language within units was encouraged and many of its recruiting posters and leaflets were printed in both English and Welsh. It was planned to give recruits distinctive uniforms made of ‘brethyn llwyd’ (trans. ‘grey cloth’) woven in Wales. These uniforms proved immediately problematic. 13 Welsh mills were contracted to produce the brethyn llwyd, each coming up with their own shade of ‘grey’ ranging from blue grey to grey to khaki to brown. In fact, the uniforms produced for the 11th Battalion Welsh Regiment by outfitters Messrs' Jotham of Cardiff were so brown that it led to the unit becoming nicknamed ‘The Chocolate Soldiers’. Supply problems were experienced from the outset and fewer than 9,000 brethyn llwyd uniforms were actually produced for the 50,000 Welshmen who had volunteered by the end of 1915. Finally, standard khaki uniforms were supplied to the Division and brethyn llwyd uniforms never reached the battlefield. (Source for this paragraph: National Museum of Wales)

Although the initial response to the recruiting campaign was enthusiastic, in the event the ‘Welsh Army Corps’ was confined to a single division. Originally numbered 43rd in Kitchener’s New Army, it was renumbered 38th in April 1915. By the Armistice 280,000 Welshmen had fought in the First World War – 28% of the male population, the largest proportion of the male population in any part of the UK.

After a period of training that was to prove largely outdated and irrelevant (eg there was no practice live-firing of machine guns) and after a struggle to find sufficient officers with experience, the Division began to move to the Front in Artois on 1 December 1915 and then moved south to prepare for the forthcoming Battle of the Somme.

The Division’s actions in 1916 and 1917 – in summary:

On 5 July 1916, the Division received orders to attack Mametz Wood two days later.

The wood was captured on 12 July. There, ‘... the Welsh division, inexperienced (it was composed of entirely volunteer Battalions) and inadequately trained, pushed the cream of Germany’s professional army back about one mile in most difficult conditions, an achievement which should rank with that of any division on the Somme …’ Colin Hughes: Mametz – Lloyd George’s’ Welsh Army’ at the Battle of the Somme, Gliddon Books 1990.

The Division’s casualties for the period 7-12 July totalled nearly 4000 including 600 killed and about 600 missing. The worst Battalion casualties were those of the 16th Welsh (Cardiff City) Battalion which had fought in the 7 July battle and then in the Wood itself on 11 July. It suffered more than 350 casualties – almost half its fighting strength. ‘On the Somme the Cardiff City Battalion died’ – Private W B Joshua, 16th Welsh.

It was to be just over a year before the Division was engaged in another major battle – the Third Battle of Ypres.

The Division’s attack on Pilkem Ridge on 31 July 1917 was a success and Field Marshal Haig was to write in 1919 that this action was an occasion which ‘reached the highest level of soldierly achievement’. Indeed, as he pointed out, ‘the 38th (Welsh) Division met and broke to pieces a German Guard Division.’

The Division later fought around St Julian and Langemark and was then moved to Armentieres just over the border in France.

38th (Welsh) Division in 1918 – an amazing story:

The Division’s artillery had played an important part in slowing down, then halting, the German attack in the Battle of the Lys in April 1918. Armentieres was captured by the Germans but they did not manage to advance much further.

Even before this, the Division’s infantry had been moved south to counter the German offensive opposite Amiens which had begun on 21 March. By 2 April the Division was five miles north-west of Albert. Following the German capture of Albert the Division took over a defensive line to the west of the town. By 2 May the

Division was holding a line from Aveluy Wood to Mesnil and fighting to win higher ground. After being withdrawn for rest on 20 May, the Division returned to the line from Aveluy Wood to Hamel and remained there until 19 July when it was withdrawn for rest and training. On 5 August the Division returned to the area of Aveluy Wood.

On 8 August the British Army returned to the offensive.

The 38th (Welsh) Division was called upon to drive the Germans back from Thiepval Ridge and advance to Pozieres. The action began on the night of 21/22 August when 14th Welsh penetrated Thiepval Wood. The following night, 22/23 August, 15th Welsh crossed the River Ancre, wading through water up to their chests and under fire. That same night 113th Brigade advanced from Albert (now recaptured) and 13th RWF captured Usna Ridge. On the night of 23/24 August more units of the Division advanced and the main attack began. 114th Brigade captured Thiepval Ridge, 113th Brigade captured La Boisselle and 115th Brigade captured Ovillers. By 16.00 the Division had advanced to a north-south line east of Ovillers having captured 634 prisoners and 143 machine guns. By the evening of 24 August 113th Brigade had pushed on to Contalmaison and the other two Brigades had taken Pozieres.

On 25 August the entire Division advanced to the line of High Wood-Mametz Wood. Mametz Wood was captured by 113th Brigade. Though High Wood remained uncaptured the advance continued on 26 August to Longueval. L/Cpl H Weale (14th RWF)* won the VC at Bazentin-le-Grand.

On 29 August 113th Brigade captured Ginchy and 13th Welsh of 114th Brigade captured Delville Wood (which had taken six weeks to capture in 1916). In the evening 10th SWB of 115th Brigade captured Les Boeufs but the advance was then held up at Morval – a strong German position. After prolonged bombardment 114th Brigade captured Morval on 1 September and 113th, Sailly Sallisel.

The advance continued to the Canal du Nord where the bridges over it had been blown. However, on 4 September 13th Welsh of 114th Brigade got across the Canal via the debris of a fallen bridge. A similar crossing was made by 14th and 15th Welsh of the same Brigade.

On 5 September the Division was withdrawn for six days’ badly needed rest.

Since 21 August the Division had advanced 15 miles, fighting all the way. It was an astonishing achievement. But the cost had been high: 3,614 men had been killed and wounded.

In 1919 the usually inarticulate Field Marshal Haig was unusually inspired to write of the beginning of this advance (against Pozieres, 21-24 August) as being ‘a most brilliant operation alike in conception and execution which, with the days of heavy but successful fighting that followed it, was of very material assistance to our general advance.’